THUMBELINA

There was once a woman who wished so very much to have a little child that she went to a fairy and said: “I should so very much like to have a little child. Can you tell me where I can get one?”

“Oh, that can be easily managed,” said the fairy. “Here is a barleycorn; it is not of the same kind as those which grow in the farmers’ fields, and which the chickens eat. Put it in a flowerpot, and see what will happen.”

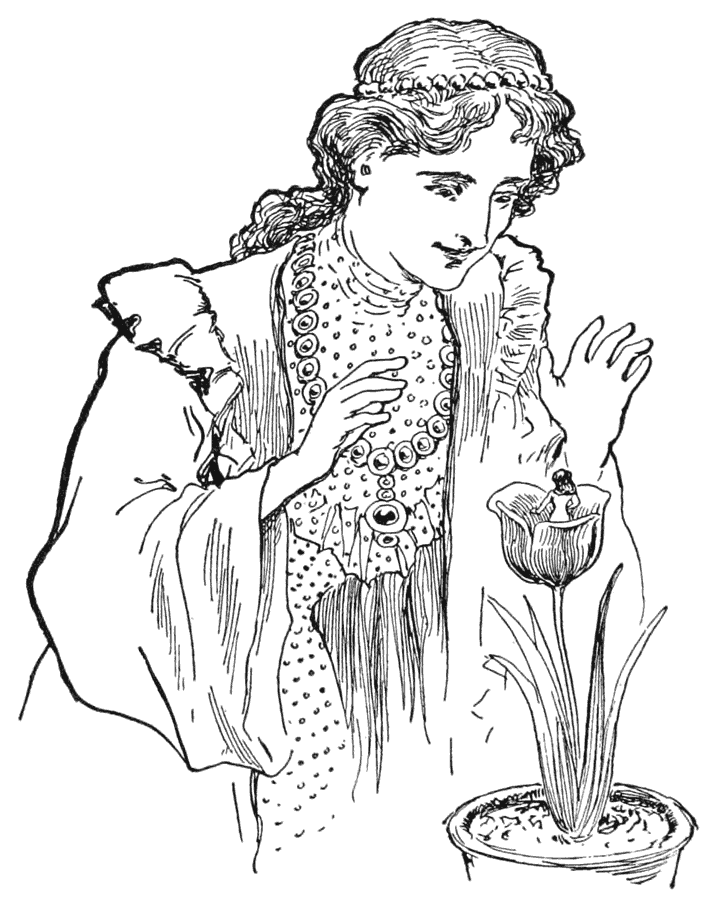

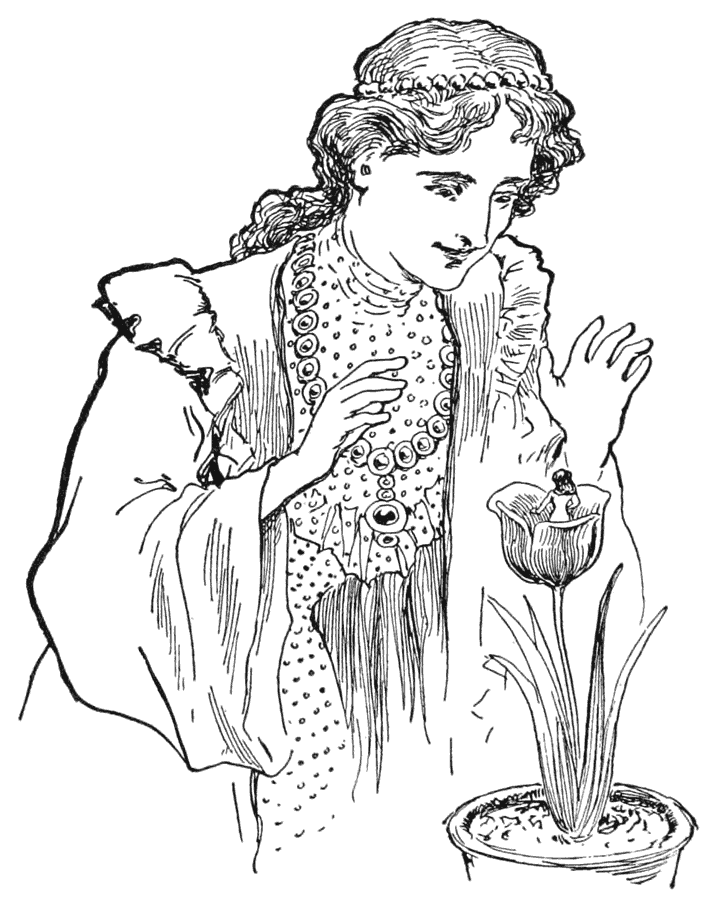

“Thank you, thank you,” said the woman; and she gave the fairy twelve shillings, which was the price of the barleycorn. Then she went home, and immediately there grew up a large, handsome flower, which looked like a tulip, except that its leaves were tightly closed as if it were still a bud.

“What a beautiful flower!” exclaimed the woman, and she kissed the red and yellow leaves; and as she kissed them the flower opened. It was a real tulip, but within the flower, upon the green velvety stamens, sat a very delicate and graceful tiny maiden. She was scarcely half as long as a thumb, so they called her Thumbelina.

A walnut shell, elegantly polished, served her for a cradle, blue violet petals were her mattress, and a rose leaf her counterpane.

Here she slept at night, but in the daytime she played upon the table, where the woman had put a bowl full of water. Round this bowl was a wreath of flowers with their stems in the water, and upon it floated a large tulip leaf, which served the little one for a boat. Here she sat and rowed herself from side to side with two white horsehairs for oars. It was a very pretty sight. Thumbelina could sing, too, so sweetly and softly that nothing like it had ever before been heard.

One night while she lay in her pretty bed, a large, ugly, wet toad crept through a broken pane of glass in the window, and hopped down on the table where Thumbelina lay sleeping under the rose-leaf quilt.

“What a pretty little wife this would make for my son,” said the toad; and she took up the walnut shell in which Thumbelina lay asleep, and jumped through the window with it into the garden.

On the marshy bank of a broad stream in the garden lived the toad with her son. He was as ugly as his mother; and when he saw the lovely little maiden in the walnut shell, all he could say was, “Croak, croak, croak!”

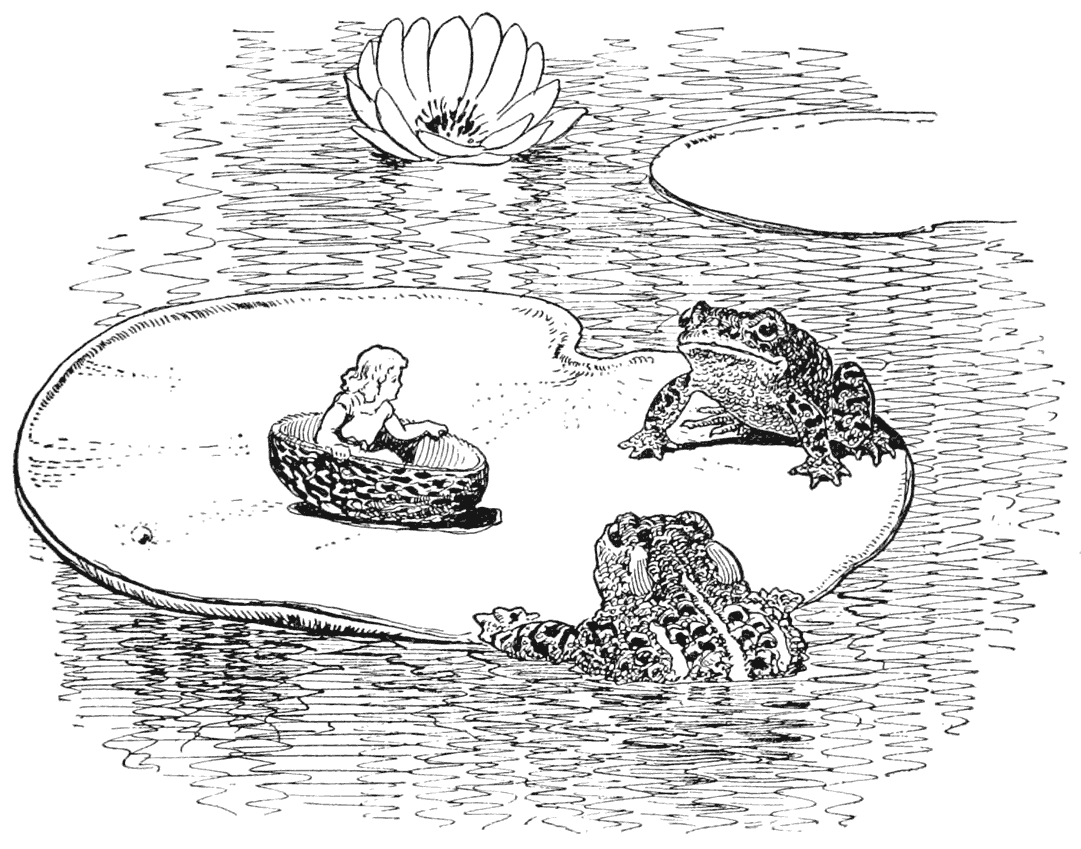

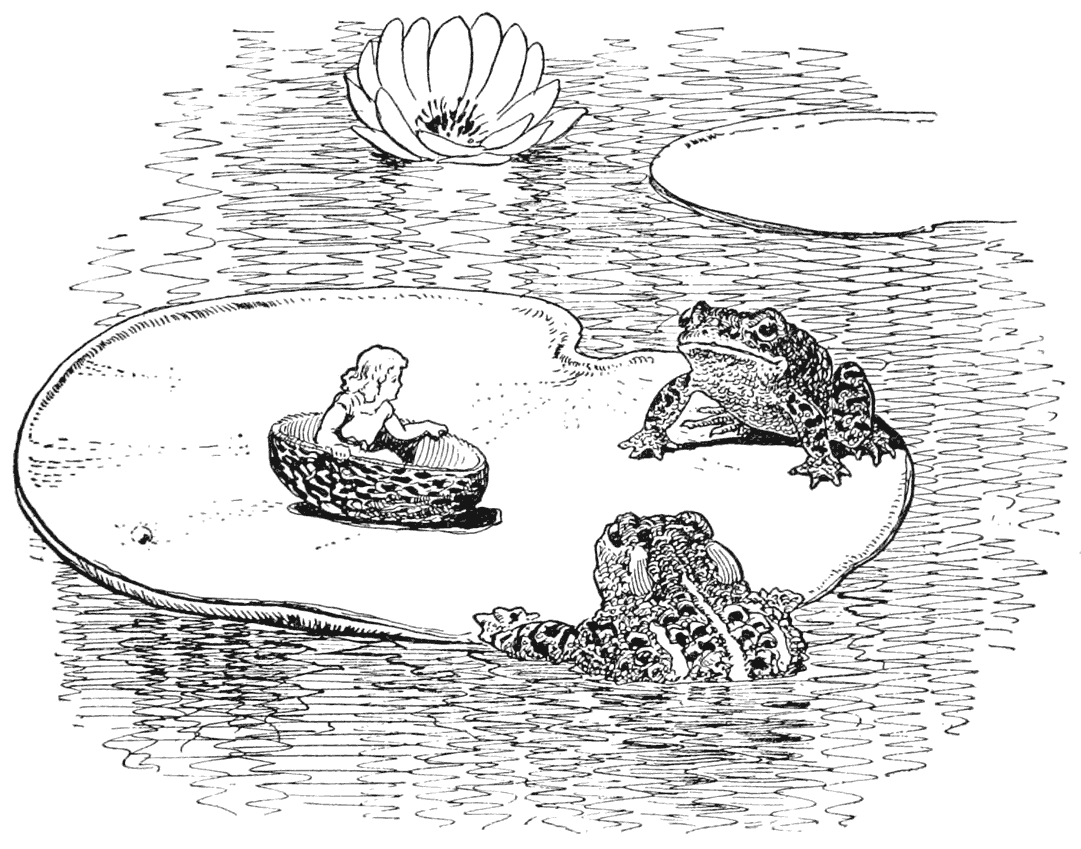

“Don’t speak so loud, or you will wake her,” said the old toad; “and then she might run away, for she is light as swan’s-down. We will take her out in the stream and put her on one of the water-lily leaves; it will be like an island to her, she is so light and small Then she can’t run away from us while we are preparing the apartments under the marsh, in which you are to live when you are married.”

Far out in the stream grew a number of water lilies, with broad green leaves which looked as if they were floating on the top of the water. The leaf that was farthest away was also the largest, and to this the old toad swam with the walnut shell in which Thumbelina lay still asleep. The tiny maiden woke very early in the morning, and began to cry bitterly when she saw where she was, for she could see nothing but water on every side of the large green leaf, and there was no way of reaching land.

Meanwhile the old toad was very busy down under the marsh, decking her room with rushes and yellow wild flowers to make it look pretty for her new daughter-in-law. Then she swam out with her ugly son to the leaf on which she had placed Thumbelina. She wanted to get the pretty bed that she might put it in the bridal chamber before Thumbelina herself came there. The old toad bowed low in the water and said, “Here is my son; he will be your husband, and you will live happily together in the marsh by the stream.”

“Croak, croak, croak!” was all the son could say for himself.

Then the toad took up the delicate little bed and swam away with it, leaving Thumbelina all alone on the green leaf, where she sat and wept. She could not bear to think of living with the old toad and having her ugly son for a husband.

The little fishes who swam about in the water beneath had seen the toad and heard what she said; so now they lifted their heads above the water to look at the little maiden. As soon as they caught sight of her and saw how very pretty she was, they felt sorry that she must go to live with the ugly toads.

“No, that must never be!” they said to one another. So they crowded together in the water round the green stalk which held the leaf on which the little maiden stood, and gnawed it away at the root with their teeth. The leaf floated down the stream, carrying Thumbelina far away out of the reach of the toad.

Thumbelina sailed past many towns, and the little birds in the bushes saw her and sang, “What a lovely little creature!” So the leaf floated farther and farther away with her till it brought her to other lands.

A pretty little white butterfly fluttered round her for a long time and at last alighted on the leaf. The maiden pleased him, and she was glad she did, for she was lonely. Taking off her girdle she tied one end of it round the butterfly, fastening the other end to the leaf, which was now gliding on much faster than before.

Presently a large cockchafer flew by. The moment he caught sight of Thumbelina he seized her round her slender waist with his claws and flew with her to a tree. The green leaf floated away down the stream, and the butterfly with it, for he was fastened to the leaf and could not get away.

Oh, how frightened Thumbelina was when the cockchafer flew with her to the tree! But especially was she distressed for the beautiful white butterfly which she had fastened to the leaf, for if he could not free himself he would die of hunger. But the cockchafer did not trouble himself at all about that; he seated himself beside her on a large green leaf, gave her some honey from the flowers to eat, and told her she was very pretty, though not in the least like a cockchafer.

Before long all the cockchafers who lived in the tree came to pay Thumbelina a visit. They stared at her, and then the young lady cockchafers turned up their feelers and said, “Why, she has only two legs! How very ugly!”

“She has no feelers,” said one.

“Her waist is quite slim. Pooh! she is like a human being,” said another.

“How ugly she is!” said all the lady cockchafers.

Then the cockchafer who had run away with her began to wonder why he had thought her so pretty, and to believe that she was as ugly as the others said. He would have nothing more to say to her, but told her she might go where she liked. Then he flew down with her from the tree and placed her on a daisy. There she sat and wept at the thought that she was so ugly that the cockchafers would have nothing to do with her. And all the while she was really the loveliest little being that one could imagine, and as tender and delicate as a beautiful rose leaf.

During the whole summer poor little Thumbelina lived quite alone in the wide forest. She wove herself a bed with blades of grass, and hung it under a broad leaf to protect herself from the rain. She sucked honey from the flowers for food, and drank the dew from the leaves every morning.

So passed away the summer and the autumn, and then came the winter,—the long cold winter. All the birds who had sung to her so sweetly had flown away, and the trees and flowers had withered. The large shamrock under the shelter of which she had lived shriveled up, leaving nothing but a yellow, withered stalk. She was dreadfully cold, for her clothes were thin and torn, and she was herself so frail and delicate that she nearly froze to death. It began to snow, too, and the snowflakes as they fell upon her were like a whole shovelful falling upon one of us, for we are tall, but she was only an inch high. She wrapped herself in a dry leaf, but it cracked in the middle and gave her no warmth, and she shivered with cold.

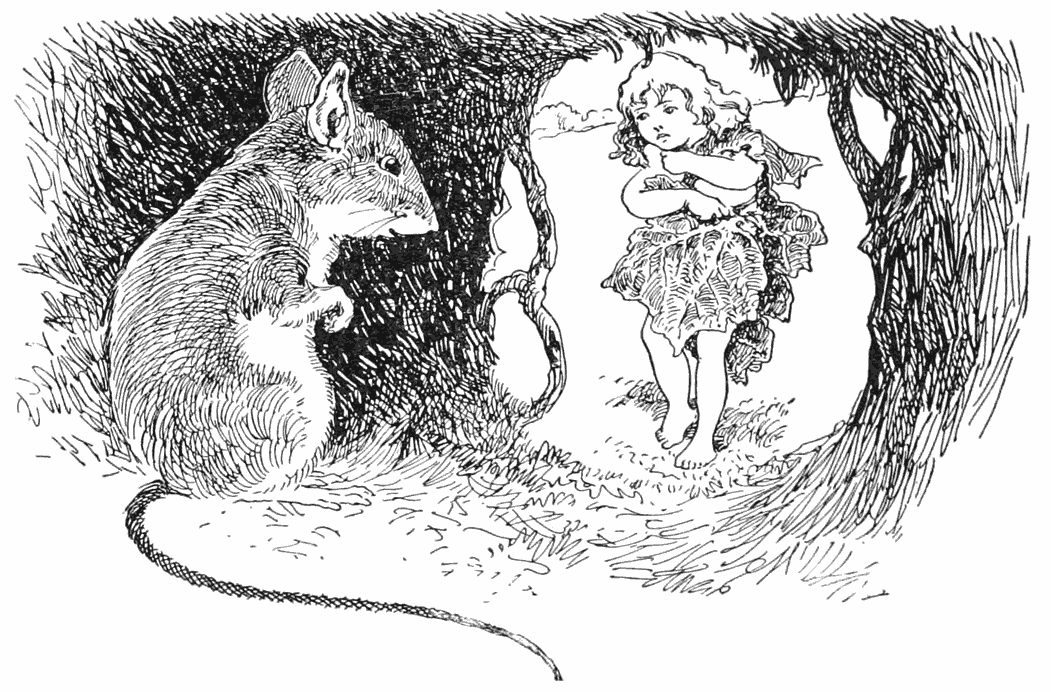

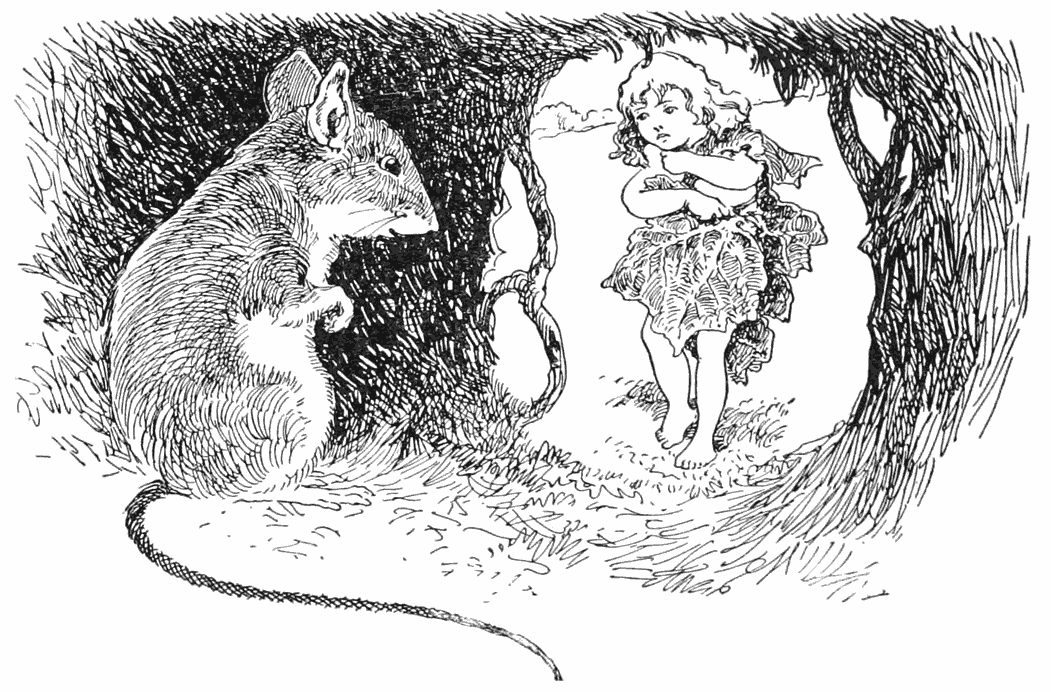

Close to the wood in which she was living was a large cornfield, but the corn had been cut a long time; nothing remained but the bare, dry stubble, standing up out of the frozen ground. It was to her like wandering about in a large wood. Oh, how she shivered with cold! All at once she came to the door of a field mouse who had a little den under the corn stubble. There lived the field mouse in warmth and comfort, with a storeroom full of corn and a splendid kitchen and dining room. Poor Thumbelina stood before the door just like a little beggar girl, and asked for a little piece of barleycorn, for she had been without a morsel to eat for two days.

“You poor little creature,” said the field mouse, for she was a good, kind-hearted old mouse; “come into my warm room and dine with me.”

Then she was pleased with Thumbelina; so she said, “You are quite welcome to stay with me all winter if you like; but you must keep my room clean and neat, and tell me stories, for I like very much to hear them.”

And Thumbelina did all that the field mouse asked her, and found herself very comfortable.

“To-night I expect a visitor,” said the field mouse one day. “My neighbor pays me a visit once a week. He is better off than I am; he has large rooms, and wears a beautiful black velvet coat. If you could only have him for a husband, you would be well provided for indeed. But he is blind. You must tell him some of your prettiest stories.”

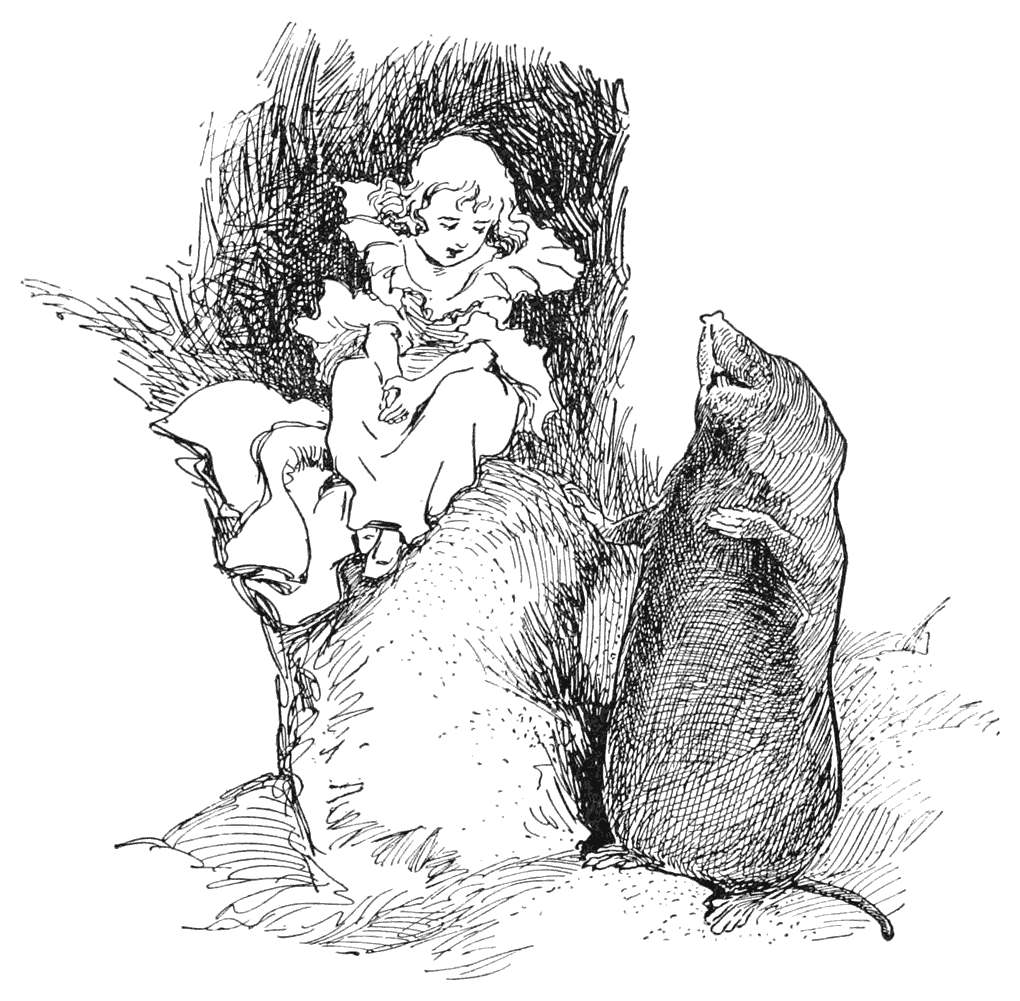

Thumbelina had no interest in this neighbor, for he was a mole. However, he came and paid them a visit, dressed in his black velvet coat.

“He is very rich and learned,” the field mouse told her, “and his house is twenty times as large as mine.”

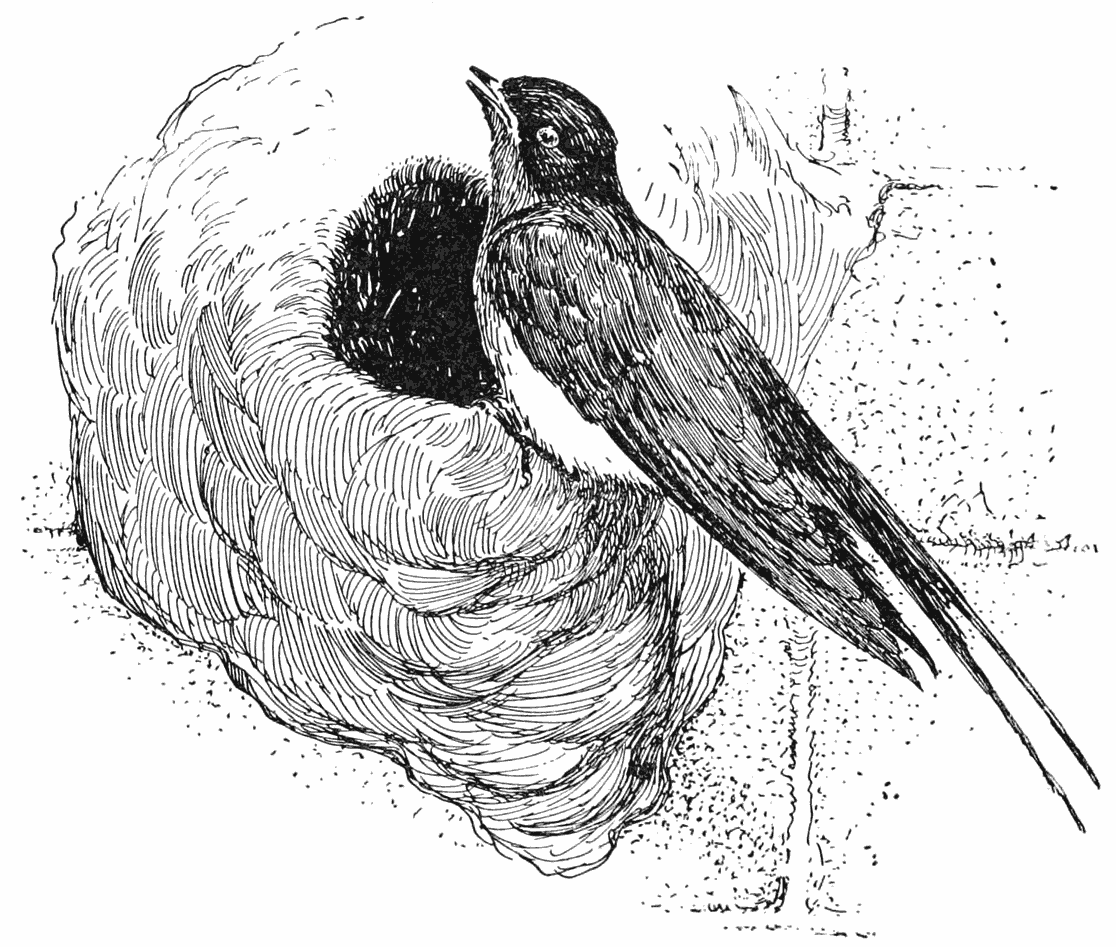

He was rich and learned, no doubt, but he always spoke slightingly of the sun and the pretty flowers because he had never seen them. Thumbelina had to sing to him, “Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home,” and many other pretty songs. And the mole fell in love with her because she had so sweet a voice; but he said nothing yet, for he was very prudent and cautious. A short time before, the mole had dug a long passage under the earth, which led from his house to that of the field mouse, and here he gave the field mouse and Thumbelina permission to walk whenever they liked. But he warned them not to be alarmed at the sight of a dead bird that lay in the passage. It was a perfect bird with a beak and feathers and could not have been dead long. It was lying just where the mole had made his passage. The mole took in his mouth a piece of decaying wood, for that will often glow in the dark like fire, and went before them, lighting them through the long, dark passage. When they came to the spot where the dead bird lay, the mole pushed his broad nose through the ceiling, so that the earth gave way and daylight shone into the passage.

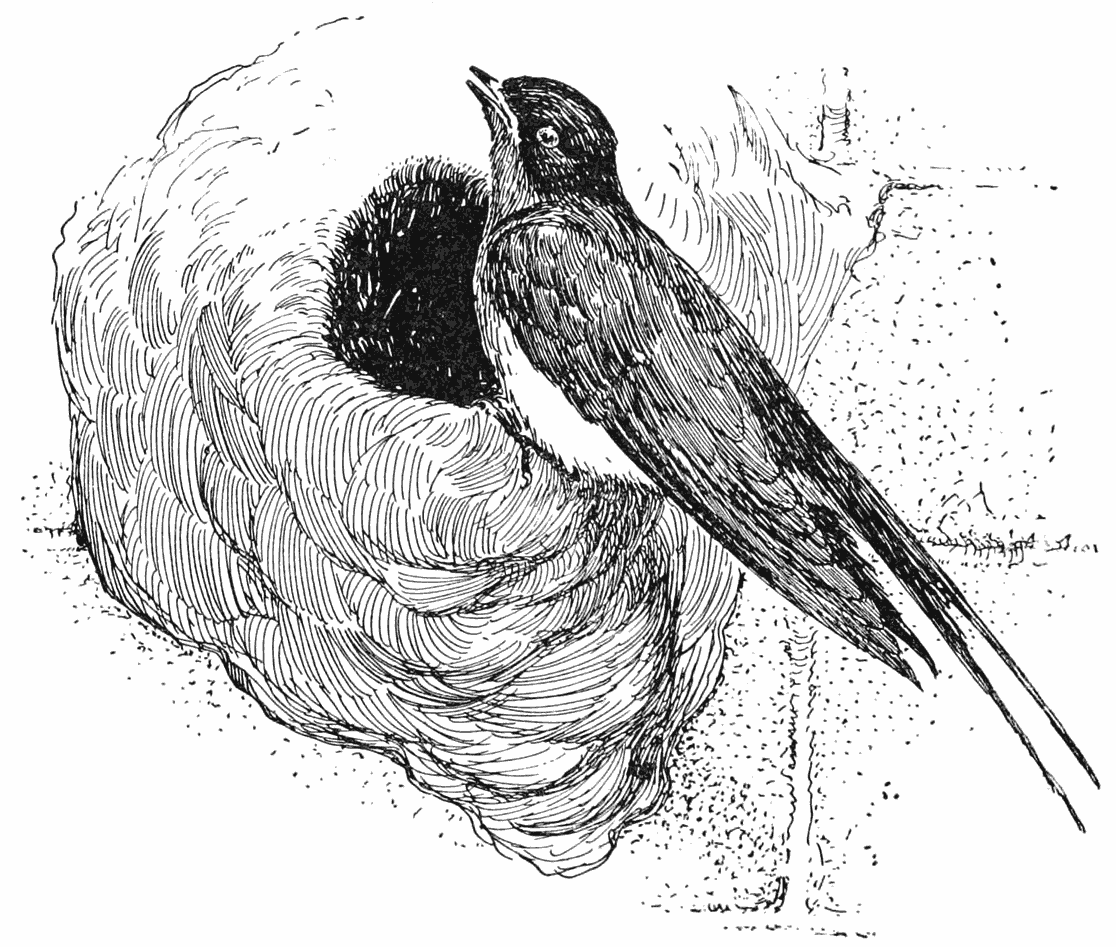

In the middle of the path lay a swallow, his pretty wings pressed close to his sides, his feet and head drawn up under his feathers; the poor bird had evidently died of cold. It made little Thumbelina very sad to see it, for she did so love the birds; all through the summer they had sung and twittered for her so beautifully. But the mole pushed it aside with his crooked legs and said: “Now he can’t sing any more! How miserable it must be to be born a little bird! I am thankful that none of my children will ever be birds, for they can do nothing but cry ‘Tweet, tweet,’ and must always die of hunger in the winter.”

“Yes, you speak like a sensible man!” exclaimed the field mouse. “What is the use of his twittering if when winter comes he must either starve or be frozen to death? That may be high-bred, but it is certainly not pleasant.”

Thumbelina said nothing, but when the two others had turned their backs on the bird she stooped down and stroked aside the soft feathers which covered the head, and kissed the closed eyelids.

“Perhaps it was he who sang to me so sweetly in the summer,” she said. “How much pleasure it gave me, you dear, pretty bird!”

The mole stopped up the hole through which the daylight shone and escorted the ladies home. But Thumbelina could not sleep that night for thinking of the cold bird; so she got out of bed and wove a large, beautiful blanket of hay. She carried it out and spread it over the dead bird, and piled upon it thistledown which she had found in the field mouse’s room, so that he might lie warmly in the cold earth.

“Farewell, pretty bird!” she said; “farewell, and thank you for your beautiful songs in the summer, when all the trees were green and the sun shone down warmly upon us.”

Then she laid her head on the bird’s breast, but she was startled, for it seemed as if something inside the bird went “thump, thump.” It was the bird’s heart; for he was not really dead, only benumbed with the cold, and the warmth had restored him to life. In autumn all the swallows fly away to warmer countries; but if one happens to linger it becomes so stiff with cold that it drops down as if it were dead, and then the snow comes and covers it.

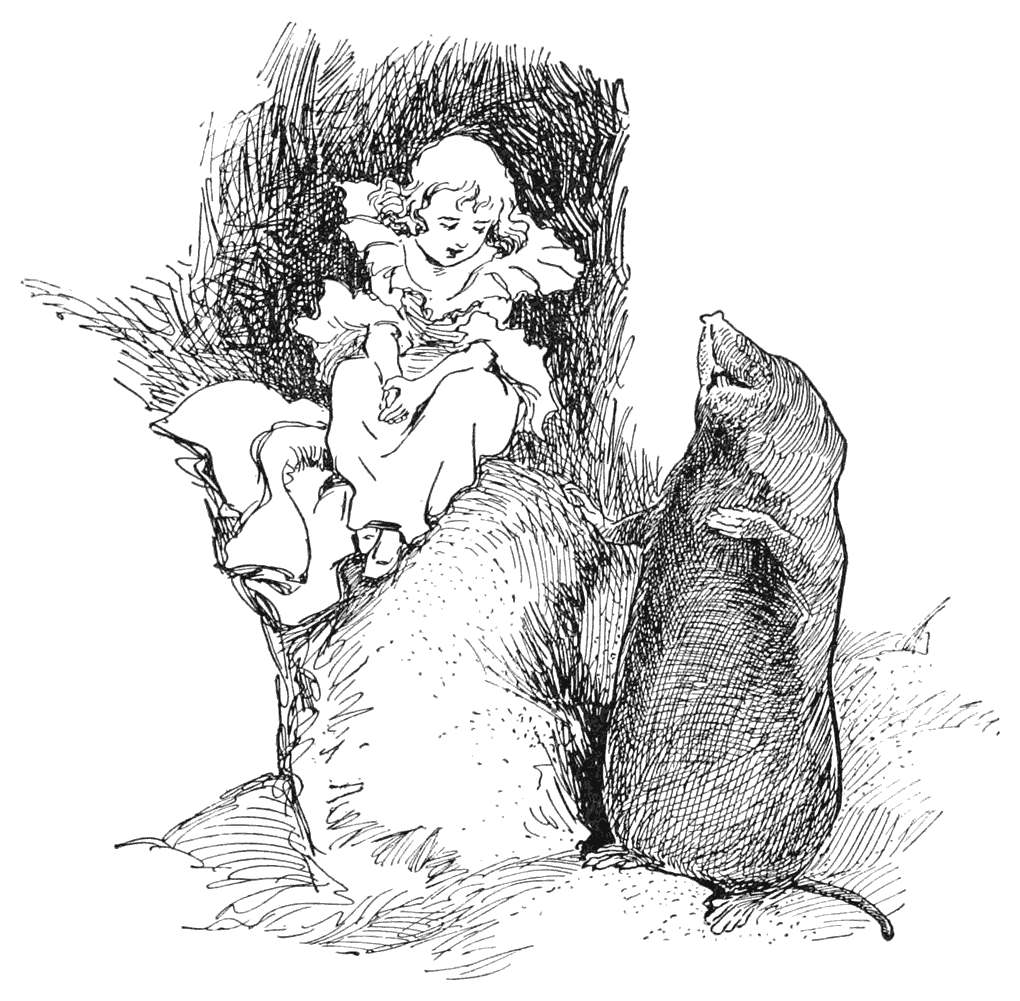

Thumbelina trembled very much; she was quite frightened, for the bird was large, a great deal larger than herself,—she was only an inch high. But she took courage, piled up the down more thickly over the poor swallow, and then took a leaf she had used for her own counterpane and laid it over his head.

The next night she stole out again to see him. He was alive but very weak; he could only open his eyes for a moment to look at Thumbelina, who stood by him with the piece of decayed wood in her hand, for she had no other lantern.

“Thank you, pretty little maiden,” said the sick swallow; “I have been so beautifully warmed that soon I shall regain my strength and be able to fly about again in the warm sunshine.”

“Oh, no!” said she; “it is very cold out of doors now; it snows and freezes. Stay in your warm bed; I will take care of you.”

She brought the swallow water in a flower leaf; and after he had drunk, he told her that he had torn one of his wings on a thorn bush and could not fly as fast as the others, who had flown far away to warm countries. At last he had fallen to the ground and could remember nothing more, nor how he came to be where she had found him.

All winter the swallow remained underground, and Thumbelina nursed and cared for him tenderly. Neither the mole nor the field mouse knew anything about it, for they could not bear swallows.

Very soon the springtime came, and the sun warmed the earth. Then the swallow bade farewell to Thumbelina and opened the hole in the roof which the mole had made. The sun shone in upon them so beautifully that the swallow asked her if she would go with him. She could sit on his back, he said, and he would fly away with her into the green woods. But she knew it would grieve the field mouse if she left her in that manner, so she said, “No, I cannot.”

“Farewell then, farewell, you good, pretty little maiden,” said the swallow; and he flew out into the sunshine.

Thumbelina looked after him, and the tears rose in her eyes. She was very fond of the swallow.

“Tweet, tweet,” sang the bird as he flew out into the green woods, and Thumbelina felt very sad. She was not allowed to go out into the warm sunshine. The corn which had been sown in the field over the house of the field mouse had grown up high in the air, and made a thick forest for Thumbelina, who was only an inch high.

“You are going to be married, little one,” said the field mouse. “My neighbor has asked for you. What good fortune for a poor child like you! Now we will set to work at your wedding clothes. You must have woolen and linen. Nothing must be wanting if you are to become the wife of the mole.”

Thumbelina had to turn the spindle, and the field mouse hired four spiders to weave for her day and night. Every evening the mole visited her and talked of the time when the summer would be over. Then he would set the wedding day for Thumbelina; but now the heat of the sun was so great that it burned the earth and made it hard like stone. Yes, as soon as the summer was over the wedding should take place. But Thumbelina was not at all pleased, for she did not like the tiresome mole.

Every morning when the sun rose, and every evening when it went down, she would steal out of the door, and when the wind blew the ears of corn aside so that she could see the blue sky, she thought how beautiful and bright it seemed out there and wished so much to see her dear swallow again. But he never came; for by this time he had flown far away into the lovely green forest.

When autumn came Thumbelina had her outfit all ready, and the field mouse said to her, “In four weeks the wedding must take place.”

But Thumbelina wept and said she would not marry the disagreeable mole.

“Nonsense,” replied the field mouse. “Now don’t be obstinate or I shall bite you with my white teeth. He is a very fine mole; the Queen herself has not such a beautiful velvet coat His kitchens and cellars are quite full. You ought to be very thankful for such good fortune.”

So the wedding day came, on which the mole was to take her away to live with him, deep under the earth, and never again to come out into the warm sunshine, because he did not like it. The poor child was very unhappy at the thought of saying farewell to the beautiful sun; she went to the door to look at it once more.

“Farewell, bright sun,” she cried, stretching out her arms towards it; and then she walked a short distance from the house, for the corn had been cut and only the dry stubble remained in the fields.

“Farewell, farewell,” she repeated, and threw her arms round a little red flower that grew just by her side. “Greet the little swallow for me if you should see him again.”

“Tweet, tweet,” sounded over her head suddenly. She looked up and there was the swallow flying close by. He was delighted to see Thumbelina. She told him how unwilling she was to marry the ugly mole and to live always deep under the earth where the sun never shone. And as she told him she wept.

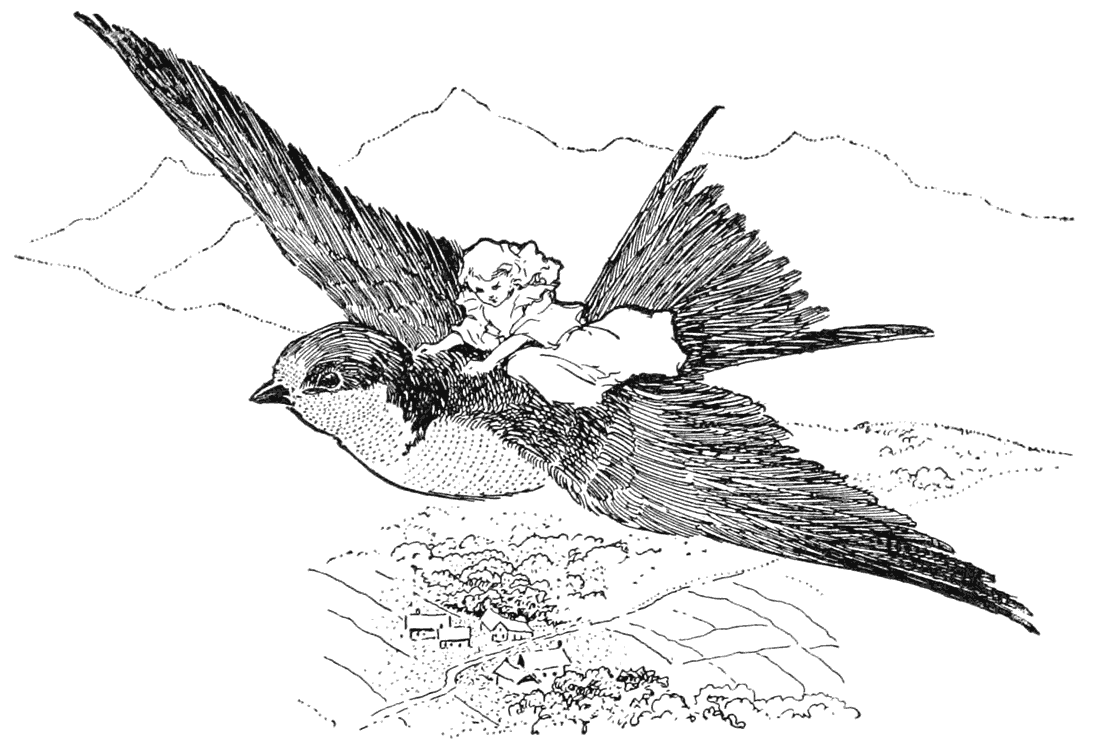

“The cold winter is coming,” said the swallow, “and I am going to fly away into warmer countries. Will you go with me? You can sit on my back and fasten yourself on with your sash. Then we can fly away from the ugly mole and his dark rooms,—far away over the mountains into warmer countries, where the sun shines more brightly than here, where it is always summer, and there are beautiful flowers. Do come with me, dear little Thumbelina; you saved my life when I lay frozen in that dark, dreary passage.”

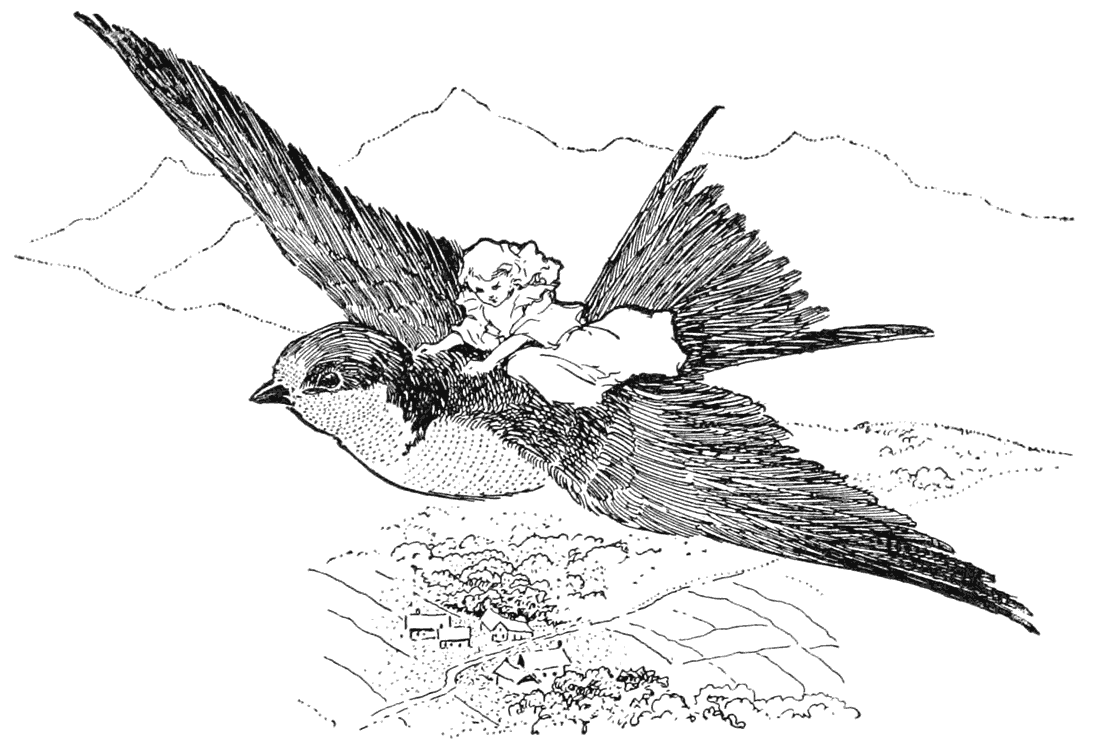

“Yes, I will go with you,” said Thumbelina, and she seated herself on the bird’s back with her feet on his outstretched wings, and bound her sash to one of his strongest feathers.

Up he flew into the air and far away, over forest and over sea, high above the highest mountains where the snow never melts. Thumbelina would have frozen in the cold air had she not crept under the bird’s warm feathers, keeping only her little head out so that she might admire the beautiful things in the world beneath. At length they reached the warm countries, where the sun shines brightly and the sky seems so much higher above the earth. Here on hedges grew the finest green, purple, and white grapes; lemons and oranges hung from the trees in the woods; and the air was fragrant with myrtles and orange blossoms. Beautiful children ran along the roads playing with gay butterflies. And as the swallow flew farther and farther south, everything became more and more beautiful.

At last they came to a blue lake, and by the side of it, shaded by magnificent trees, stood a palace of dazzling white marble, built in olden times. Vines clustered round its lofty pillars, and at the top were many swallows’ nests, and one of these was the home of the swallow who carried Thumbelina.

“That is my house,” said the swallow, “but it would not do for you to live there; you would not be comfortable. Choose for yourself one of those lovely flowers and I will put you down on it, and then you shall have everything you wish to make you happy.”

“That will be delightful,” she said, and clapped her little hands for joy.

On the ground lay a large marble pillar, which in falling had broken into three pieces. Between these fragments grew the most beautiful great white flowers. So the swallow flew down with Thumbelina and set her on one of the broad leaves. But how surprised he was to see, sitting in the middle of the flower, a tiny little man, as white and transparent as if he had been made of crystal! He had the prettiest gold crown on his head, and delicate wings at his shoulders, and was no bigger than Thumbelina. He was the fairy of the flower; for in every flower dwelt a tiny man or woman, and this was the King over them all.

“Oh, how beautiful he is!” whispered Thumbelina to the swallow.

The little Prince was very much frightened at the swallow, who was like a giant compared to such a tiny little being as he; but when he saw Thumbelina he was delighted, for he thought her the prettiest little maiden he had ever seen. He took the gold crown from his head and placed it on hers, and asked her name, and if she would be his wife and Queen over all the flowers.

This was certainly a very different kind of husband from the son of the toad or the mole with his black velvet coat; so she said Yes to the handsome Prince. Then out of each flower came a little lady or a tiny lord, all so pretty that it was a pleasure to look at them. Each brought Thumbelina a present; but the best gift of all was a pair of beautiful white wings, which were fastened to her shoulders, and now she, too, could fly from flower to flower.

Then there was much rejoicing, and the swallow sat in his nest above and sang the wedding song as well as he could; but in his heart he felt sad, for he was very fond of Thumbelina and would have liked never to part with her.

“You must not be called Thumbelina any more,” said the Prince to her; “for that is an ugly name, and you are so very lovely. We will call you Maia.”

“Farewell, farewell,” sang the swallow with a heavy heart as he left the warm countries to fly back again to Denmark. There he had a nest over the window of a man who wrote fairy tales. The swallow sang his “Tweet, tweet,” and from his song we have the whole story.