RIQUET WITH THE TUFT

There was once a queen who had a son so ugly and misshapen that it was questioned for a long time whether he was a human creature or not. A fairy who was present at his birth declared that he would be none the less amiable for all his ugliness, because he would have uncommon intelligence and wit. She added that he would have the power, by virtue of a gift which she had just bestowed upon him, to give the same talents which he possessed to the person whom he should love best. All this was some comfort to the poor Queen, who was in great distress at having such an unsightly child.

As soon as the child began to talk he said a thousand pretty things, and in everything he did he was so unusually clever that every one was delighted with him. I forgot to tell you that he was born with a little tuft of hair on his head, and on this account they called him Riquet with the Tuft; for Riquet was the family name.

Seven or eight years after this the Queen of a neighboring kingdom had twin daughters. The firstborn was more beautiful than the day. The Queen was so very happy over this that it was feared that such excess of joy would do her harm. The same fairy who had been present at the birth of little Riquet with the Tuft was here too; and to moderate the Queen’s joy she told her that this little Princess should have no sense at all, but should be as stupid as she was pretty. This mortified the Queen very much, but soon she had a still greater sorrow, for the second daughter was extremely ugly.

“Do not afflict yourself so much, madam,” said the fairy. “Your daughter shall have it made up to her in other ways; she shall have so much intelligence and wit that her want of beauty will hardly be noticed.”

“God grant it may be so,” replied the Queen; “but is there no way to make the elder, who is so pretty, have a little sense?”

“I can do nothing for her in the matter of sense,” said the fairy, “but everything in the matter of beauty; and therefore, as there is nothing I would not do for your satisfaction, I will bestow on her as a gift the power to make handsome the person whom she likes best.”

As the two Princesses grew older, their perfections grew with them. Everywhere people talked of the beauty of the elder and of the wit of the younger. It is true that their defects increased considerably with their years. The younger grew visibly uglier, and the elder became more stupid every day; either she made no reply to what was asked her, or she said something very silly. She was, besides, so clumsy that she could not place four pieces of china on the mantelpiece without breaking one, nor drink a glass of water without spilling half of it on her clothes.

Although beauty is a great advantage to a young girl, in society the younger sister was almost always preferred to the elder. People would go first to the more beautiful to see and admire her; but they very soon left her for the more clever sister, to enjoy listening to her pleasant conversation; and it was amazing to see how in less than a quarter of an hour the elder was without a person near her, while the whole company was crowding about the younger. The elder, dull as she was, noticed this very plainly, and would have given, without a moment of regret, all her beauty to have half the wit of her sister. The Queen, for all her good sense, could not help reproaching her often for her stupidity; this made the poor Princess ready to die of grief.

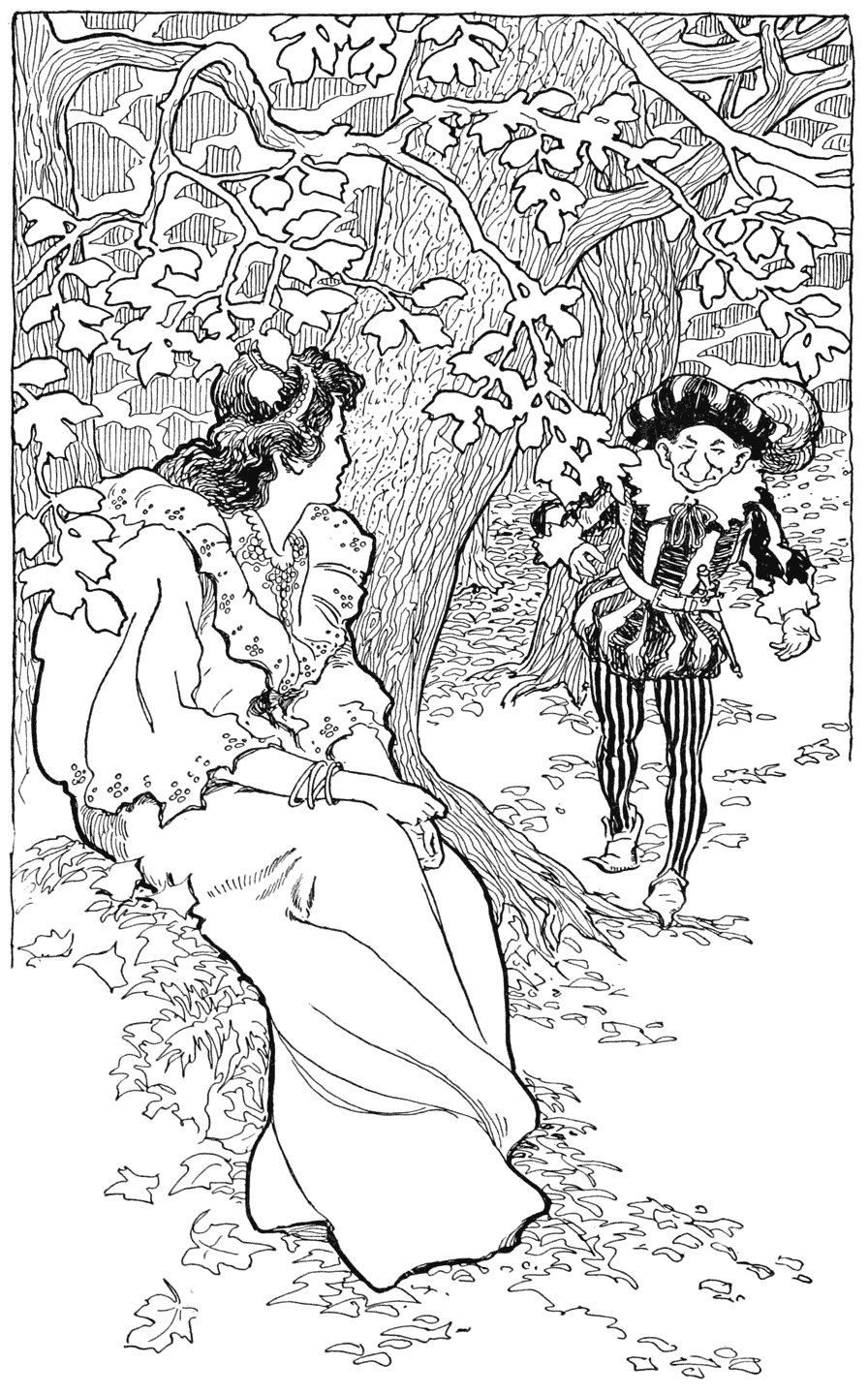

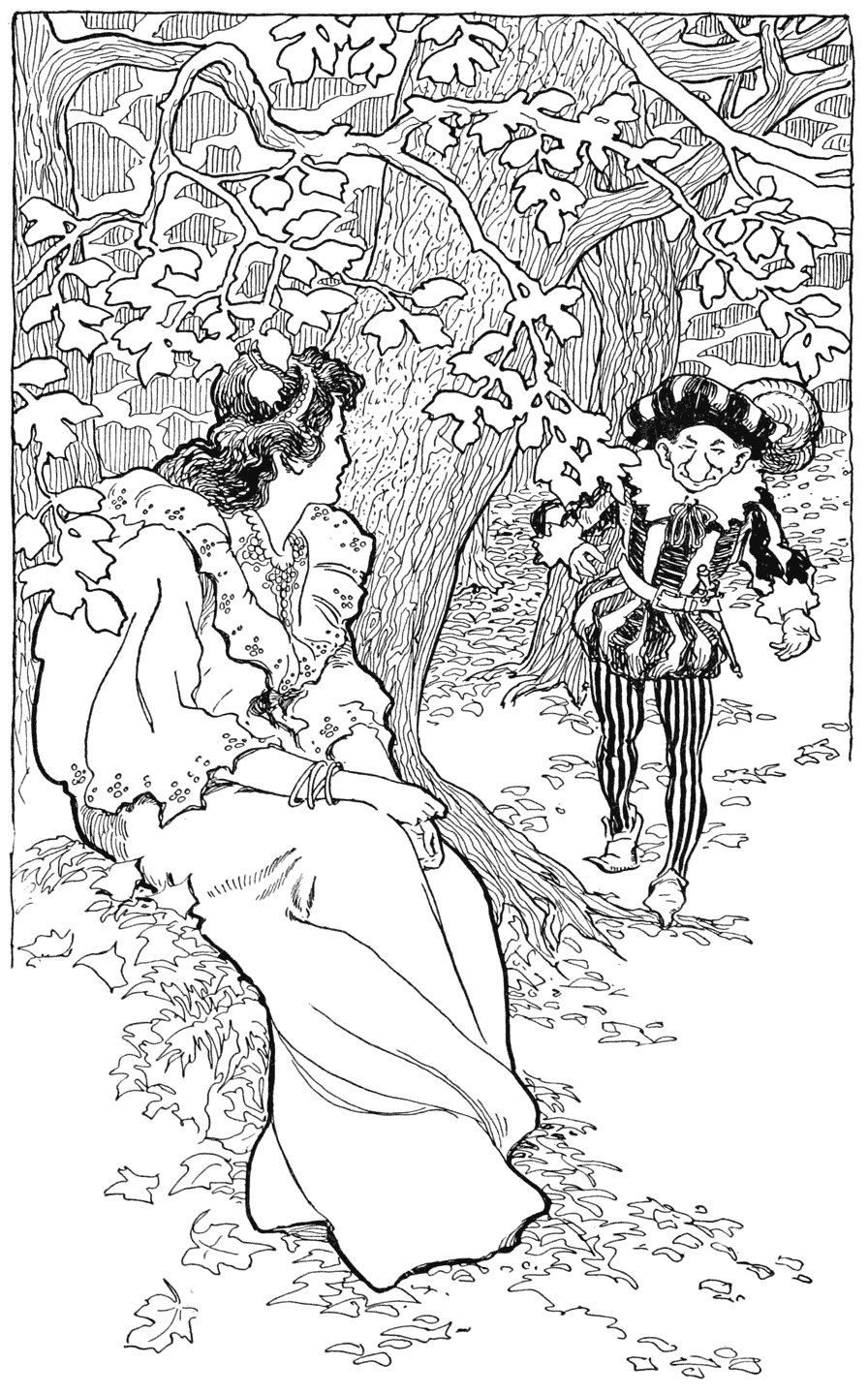

One day, when she had withdrawn to a wood near by to lament her misfortune, she saw coming towards her an ugly little man, very unpleasant to look at, but most magnificently dressed. It was the young Prince Riquet with the Tuft, who had fallen in love with her from her portraits, which were scattered everywhere, and had now left his father’s kingdom to have the pleasure of seeing her and talking with her. He was charmed at finding her thus alone, and addressed her with all imaginable respect and politeness. Having observed, after he had paid her all the usual compliments, that she seemed very melancholy, he said to her, “I cannot understand, madam, how a person as beautiful as you are can be also as sorrowful as you appear to be; for although I can boast of having seen a great number of beautiful ladies, I declare to you that I never saw any one whose beauty approaches yours.”

“You are very kind to say so, sir,” answered the Princess; and here she stopped.

“Beauty,” replied Riquet with the Tuft, “is so great an advantage that it ought to make up for all else; and when any one possesses it, I do not see that there is anything that can afflict her very much.”

“I would much rather,” said the Princess, “be as ugly as you are and have sense, than have the beauty which I possess, and be as stupid as I am.”

“There is nothing, madam, which shows more plainly that we have sense than to believe we have none; and it is the nature of that gift that the more people have it, the more they believe they lack it.”

“I do not know how that may be,” said the Princess, “but I know very well that I am extremely stupid, and that is the cause of my grief.”

“If that is all which troubles you, madam, I can very easily put an end to your sorrow.”

“And how will you do that?” said the Princess.

“I have the power, madam,” said Riquet with the Tuft, “of giving to that person whom it is my fortune to love best as much wit as it is possible to have; and as you, madam, are that person, it will only depend on yourself if you have not as much wit as any one can have, provided only you are pleased to marry me.”

The Princess was much confused and did not speak a word.

“I see,” continued Riquet with the Tuft, “that this proposal disturbs you, and I do not wonder at it; but I will give you a whole year in which to make up your mind about it.”

The Princess had so little sense, and at the same time so great a desire to have some, that she imagined that the end of this year would never come; so she accepted the proposal which was made to her. She had no sooner promised Riquet with the Tuft that she would marry him in a year from that day than she realized a great change in herself; she found herself saying with incredible ease whatever she wished, and saying it, too, in a clever, fluent, and natural manner.

She began at that moment a brilliant conversation with Riquet with the Tuft, which she sustained with such ease that Riquet began to think that he had given her more wit than he had reserved for himself.

When she returned to the palace the court did not know what to think of so sudden and extraordinary a change; for now she said as many sensible and extremely clever things as before she had said stupid and silly ones. The whole court was delighted beyond measure over it; the younger sister was the only one who did not share the general happiness; for, having no longer any advantage over her sister in the line of wit and sense, she appeared beside her a homely, disagreeable girl.

The King himself was now guided by the advice of the elder sister, and sometimes would even hold a meeting of the council in her apartments. As the report of this change spread everywhere, all the young Princes of neighboring kingdoms made efforts to gain her favor, and almost all of them asked for her hand in marriage; but she did not find any one who had enough wit to satisfy her. So she heard them all without binding herself to any one of them.

However, there came one so powerful, so rich, so witty, and so handsome that she could not help feeling a great liking for him. When her father saw this he told her that he was leaving her to be her own mistress in the matter of choosing a husband, and that she had only to express her wishes. She was so sensible that she knew so serious a matter deserved her careful consideration; so she thanked her father and asked him to give her time to think it over.

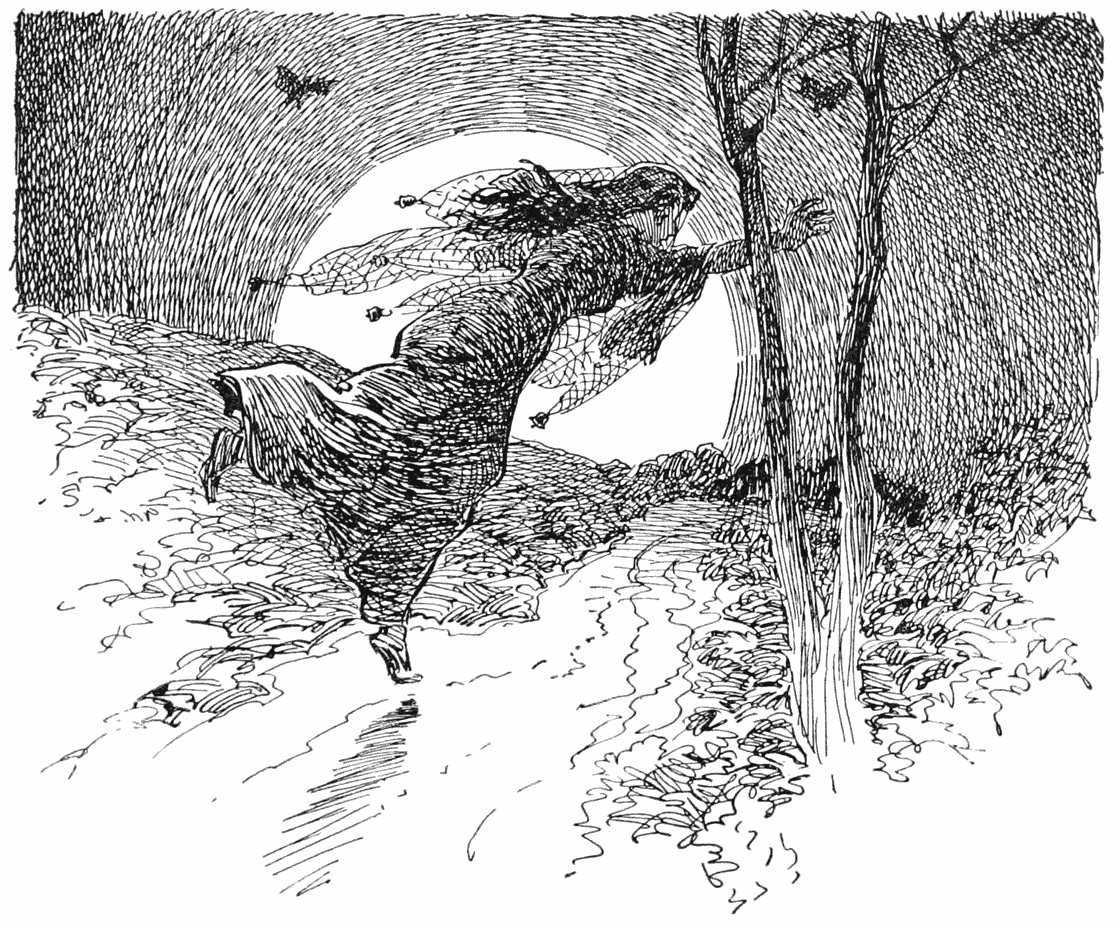

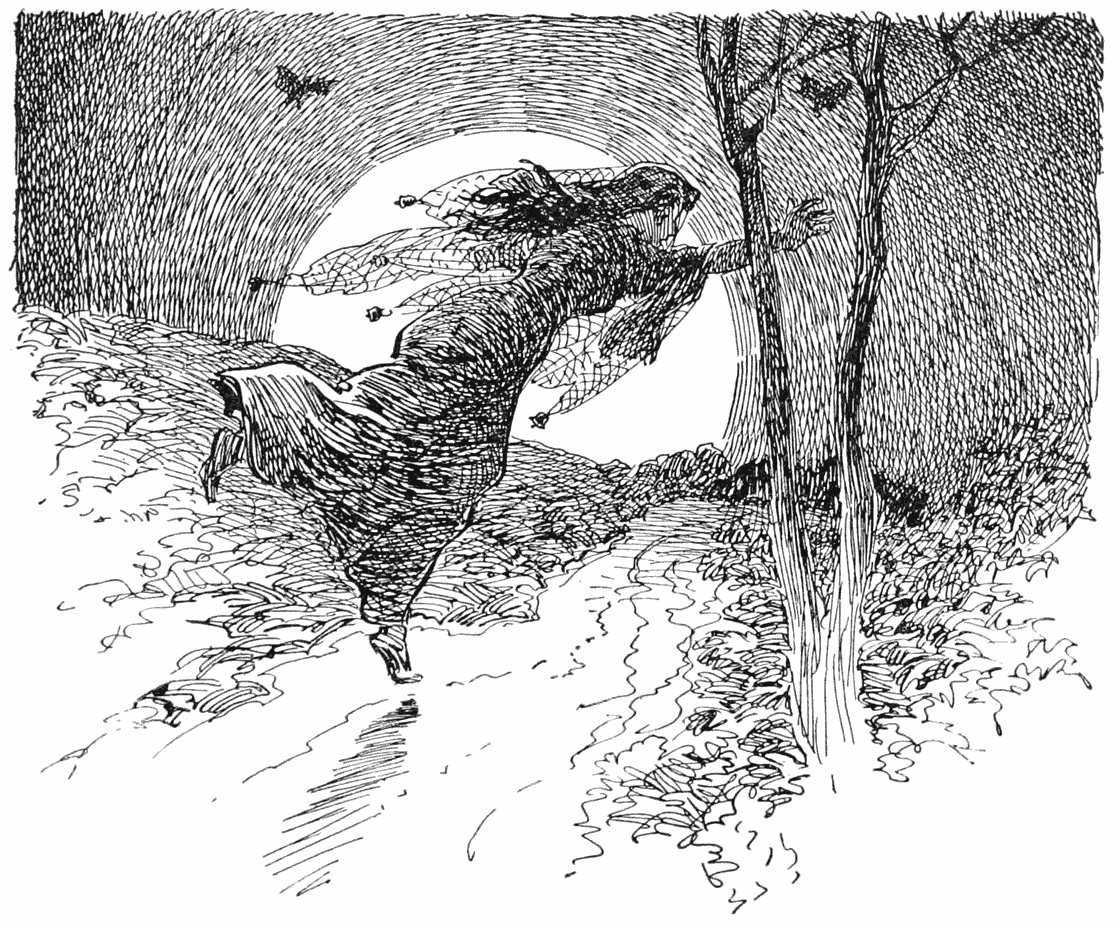

She went, by chance, to walk in the same wood where she had met Riquet with the Tuft, to deliberate on what she should do. While she was walking in deep reflection she heard a dull noise under her feet, as of a great many people running busily to and fro. Listening more attentively she heard one say, “Bring me that saucepan”; another, “Give me that kettle”; and a third, “Put some wood on the fire.”

At that moment the ground opened, and she saw under her feet a great kitchen full of cooks, scullions, and all sorts of servants and people necessary to prepare a magnificent feast. There came forward a company of twenty or thirty cooks, with larding needles in their hands and foxtails in their caps, who took their places in one avenue of the wood about a very long table, and went to work busily, keeping time with a tuneful song.

The Princess, in astonishment at the sight, asked them for whom they were working.

“For Prince Riquet with the Tuft, madam, whose wedding takes place to-morrow,” replied their chief.

The Princess, more surprised than ever, remembered all at once that it was that day twelvemonth on which she had promised to marry Prince Riquet. At the thought she was ready to sink into the ground. What made her forget was that when she made the promise she was very silly; and when she took the new sense that the Prince bestowed on her, she forgot all that she had done in the days of her stupidity. She walked on, but had not taken thirty steps before Riquet with the Tuft presented himself before her, magnificently attired like a man who was going to be married.

“You see, madam,” said he, “that I am exact in keeping my word; and I do not doubt that you are come to fulfill yours, and to make me, by giving me your hand, the happiest man in the world.”

“I will confess frankly to you,” replied the Princess, “that I have not yet made up my mind in this matter, and that I do not believe that I shall ever be able to consent to what you desire.”

“You astonish me, madam,” said Riquet with the Tuft.

“That I can well believe,” said the Princess; “and assuredly if I had to do with a clown or a man of no sense, I should find myself very much at a loss. ‘A Princess always keeps her word,’ he would say to me, ‘and you must marry me, since you have promised to do so.’ But as he to whom I speak is the man of all others in the world who has the most sense, I am sure he will hear reason. You know that when I was only a fool I could hardly make up my mind to marry you. Now that I have the sense which you gave me, which makes me much harder to please, how can you expect me to come to a decision to-day which I could not agree to before? If you thought seriously of marrying me, you made a great mistake in removing my stupidity and making me see things more plainly than I did before.”

“If a man without wit or sense,” replied Riquet, “would be justified in reproaching you for breaking your word, why do you wish, madam, that I should not make use of the same right in a matter where the happiness of my whole life is at stake? Is it reasonable that persons of wit and sense should be worse off than those who have none? Can you pretend this,—you who are so wise and who wished so much to be? But come to the point, if you please. Except for my ugliness is there anything in me which displeases you? Do you object to my birth, my sense, my temper, or my manners?”

“Not at all,” said the Princess; “I like in you all that you have mentioned.”

“If that is the case,” replied Riquet with the Tuft, “I shall soon be happy, for you have the power to make me the most handsome of men.”

“How can that be?” asked the Princess.

“It can be done,” replied Riquet with the Tuft, “if you love me enough to desire that it should be; and in order that you may have no doubt about it, know that the same fairy who at my birth bestowed on me the power of making clever the person I love best, has given you the power of making as handsome as you please him whom you love best and for whom you desire this favor.”

“If that be the case,” said the Princess, “I wish with all my heart that you may be the comeliest and handsomest Prince in the world, and I bestow on you this gift in so far as I am able.”

The Princess had no sooner pronounced these words than Riquet with the Tuft seemed to her eyes the comeliest, handsomest, and most pleasing man she had ever seen.

Some people say that it was not the fairy’s charm, but love alone which made this great change. They declare that the Princess, when she had reflected upon the perseverance of her lover, upon his discretion, and all the good qualities of his heart and mind, saw no longer the deformity of his body nor the ugliness of his face; that his hump seemed to her no more than the grand air of a man who put on a look of importance; that where before she had noticed that he limped badly, she now found it nothing more than a careless grace of carriage which charmed her. They tell, too, how his eyes, which were squinting, appeared to her on that account the more brilliant, while their irregularity passed in her judgment as a mark of the warmth of his love; and finally that his great red nose gave, in her opinion, a martial and heroic air to his appearance.

However that may be, the Princess promised immediately to marry him, provided he obtained the consent of the King her father. The King knew that his daughter had a high esteem for Riquet with the Tuft, and was well informed, too, as to the cleverness and prudence of the Prince. So he received him gladly as his son-in-law. The next day their wedding was celebrated as Riquet with the Tuft had foreseen, and according to the orders which he had given long before.