THE EMPEROR’S NEW CLOTHES

Many years ago there lived an Emperor who was so fond of new clothes that he spent all his money on them. He cared nothing about his soldiers, or about the theater, or about driving, except for the sake of showing off his new clothes. He had a coat for every hour of the day; and just as they say of a King, “He is in the council chamber,” here they always said, “The Emperor is in his wardrobe.”

In the great city in which he lived life was very gay. Every day many strangers arrived. One day two rogues came who gave themselves out to be weavers, and said that they could weave the finest cloth any one could imagine. Not only were its colors and patterns uncommonly beautiful, but the clothes which were made of this material possessed the wonderful property of becoming invisible to any one who was not fit for the office he held, or who was uncommonly stupid.

“Those must indeed be capital clothes,” thought the Emperor. “If I wore them I could find out which men in my kingdom are unfit for the offices they hold; I could distinguish the wise men from the stupid. Yes, some of that cloth must be woven for me at once.”

So he paid both the rogues a large sum of money in advance so that they might begin their work at once.

They put up two looms and went through all the motions of weaving, but they had nothing at all on their looms. They also demanded the finest silk and the purest gold thread,—all of which they put into their own pockets; and they went on working away at the empty looms all day long and far into the night.

“I should like to know how those weavers are getting on with the stuff,” thought the Emperor. But he felt a little queer when he remembered that any one who was stupid or unfit for his post would not be able to see it. He felt very sure that he had nothing to fear for himself, but still he preferred to send some one else first to see how the weaving was getting on. Everybody in the town knew what a wonderful power the cloth had, and all were curious to see how bad or how stupid their neighbors were.

“I will send my faithful and honored old minister to the weavers,” thought the Emperor. “He can judge best what the stuff is like, for he is clever, and no one fulfills his duties better than he does.”

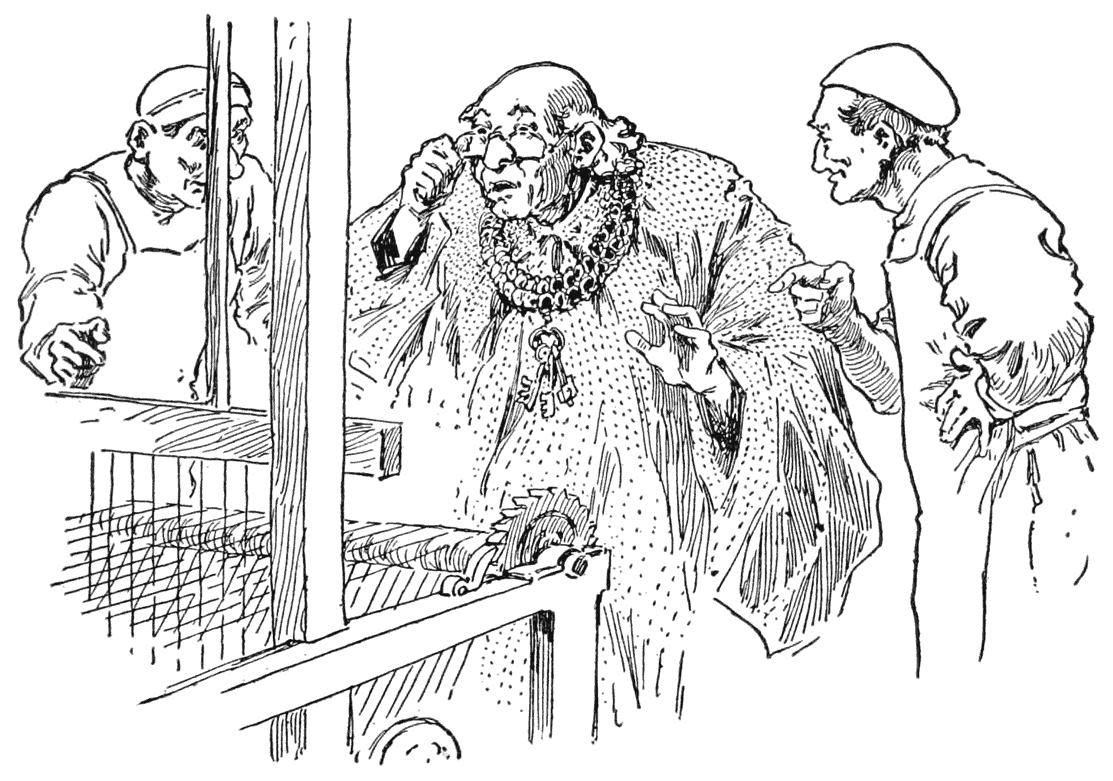

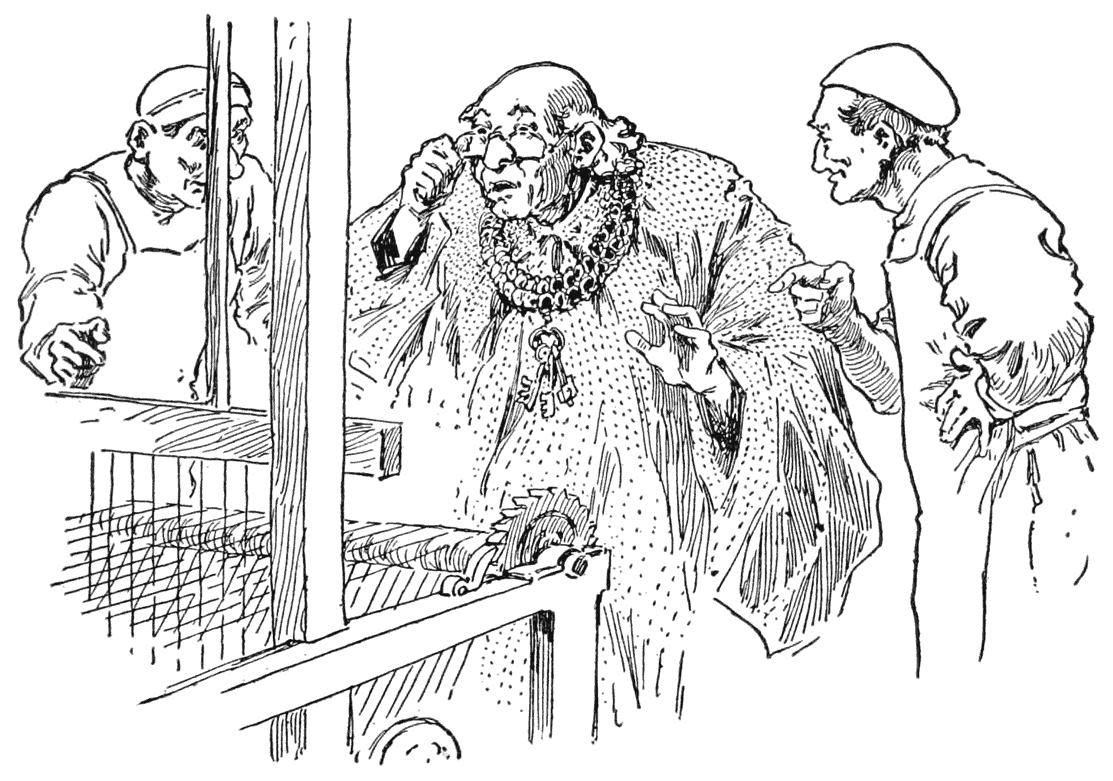

So the good old minister went to the hall where the two rogues sat working at the empty looms.

“Heaven preserve us!” thought the old minister, opening his eyes wide. “I cannot see anything at all.” But he did not say so.

Both the rogues begged him to be so good as to step a little closer, and asked him if he did not think the pattern and the colors beautiful. They pointed to the empty loom, and the poor old minister walked forward, rubbing his eyes; but he could see nothing, for there was nothing there. “Mercy on us!” thought he; “can I be so stupid? I have never thought so, and nobody must know it. Can it be that I am not fit for my office? No, it will certainly never do to say that I cannot see the cloth.”

“Have you nothing to say about it?” asked one of the weavers.

“Oh, it is beautiful! quite charming!” answered the old minister, looking through his spectacles. “What a fine pattern! and what colors! Yes, I will tell the Emperor that it pleases me very much.”

“Now we are delighted to hear you say so,” said both the weavers, and then they named all the colors, and described the peculiar pattern.

The old minister paid great attention, so that he might be able to repeat it to the Emperor when he got back.

Then the rogues wanted more money, more silk, and more gold, to use in their weaving, but they put it all into their own pockets; not a single thread was ever put on the loom, but they went on working at the empty looms as before.

Soon the Emperor sent another worthy statesman to see how the weaving was getting on, and how soon the cloth would be finished. It was the same with him as with the first one: he looked and looked, but as there was nothing on the loom he could see nothing.

“Is it not a beautiful piece of cloth?” asked the rogues, and they pointed to and described the splendid material that was not there at all.

“I am not stupid,” thought the man, “so it must be that I am not fit for my good office. It is very strange, but I must not let it be noticed.”

So he praised the cloth which he did not see, and expressed to them his delight in the beautiful colors and the charming pattern.

“Yes, it is perfectly beautiful,” he reported to the Emperor.

Everybody in the town was talking of the magnificent cloth. The Emperor himself wished to see it while it was still on the loom. With a great crowd of carefully selected men, among whom were the two worthy statesmen who had been before, he went to visit the cunning rogues, who were weaving away with might and main, but without fiber or thread.

“Is it not splendid?” said both the old statesmen. “See, Your Majesty, what a pattern! what colors!” And they pointed to the empty loom, for they believed others could see the cloth quite well.

“What!” thought the Emperor; “I can see nothing. This is terrible! Am I stupid? Am I not fit to be Emperor? That would be the most dreadful thing that could happen to me. Oh, it is very beautiful!” he said aloud. “It has my highest approval.” And then he nodded pleasantly as he examined the empty loom, for he would not say that he could see nothing.

His whole suite gazed and gazed, and saw no more than the others; but, like the Emperor, they all exclaimed, “Oh, it is beautiful! beautiful!” and they advised him to wear the splendid new clothes for the first time at the great procession which was soon to take place.

“Splendid! Gorgeous! Magnificent!” went from mouth to mouth. Every one seemed delighted, and the Emperor gave the rogues the title of “Court Weavers of the Emperor.”

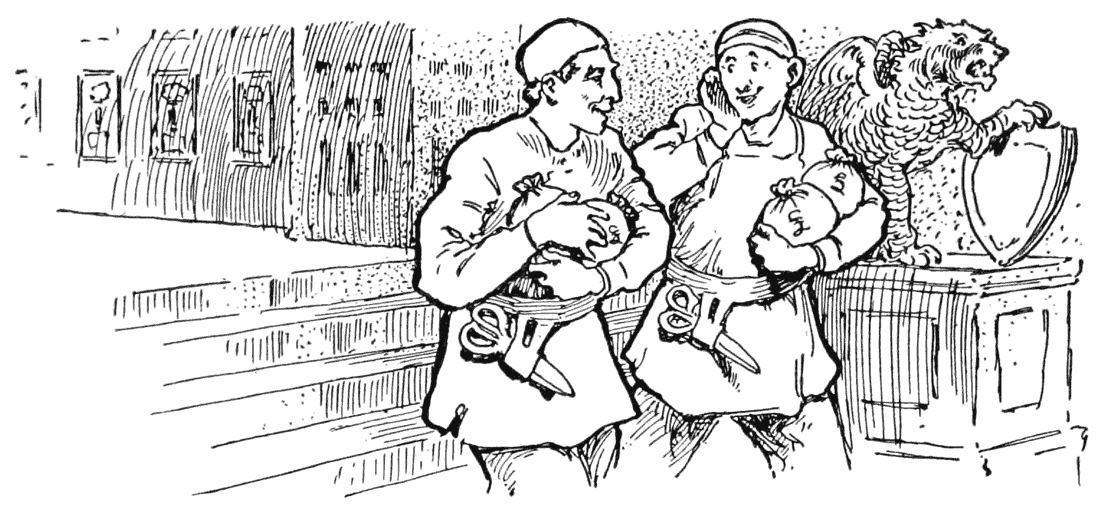

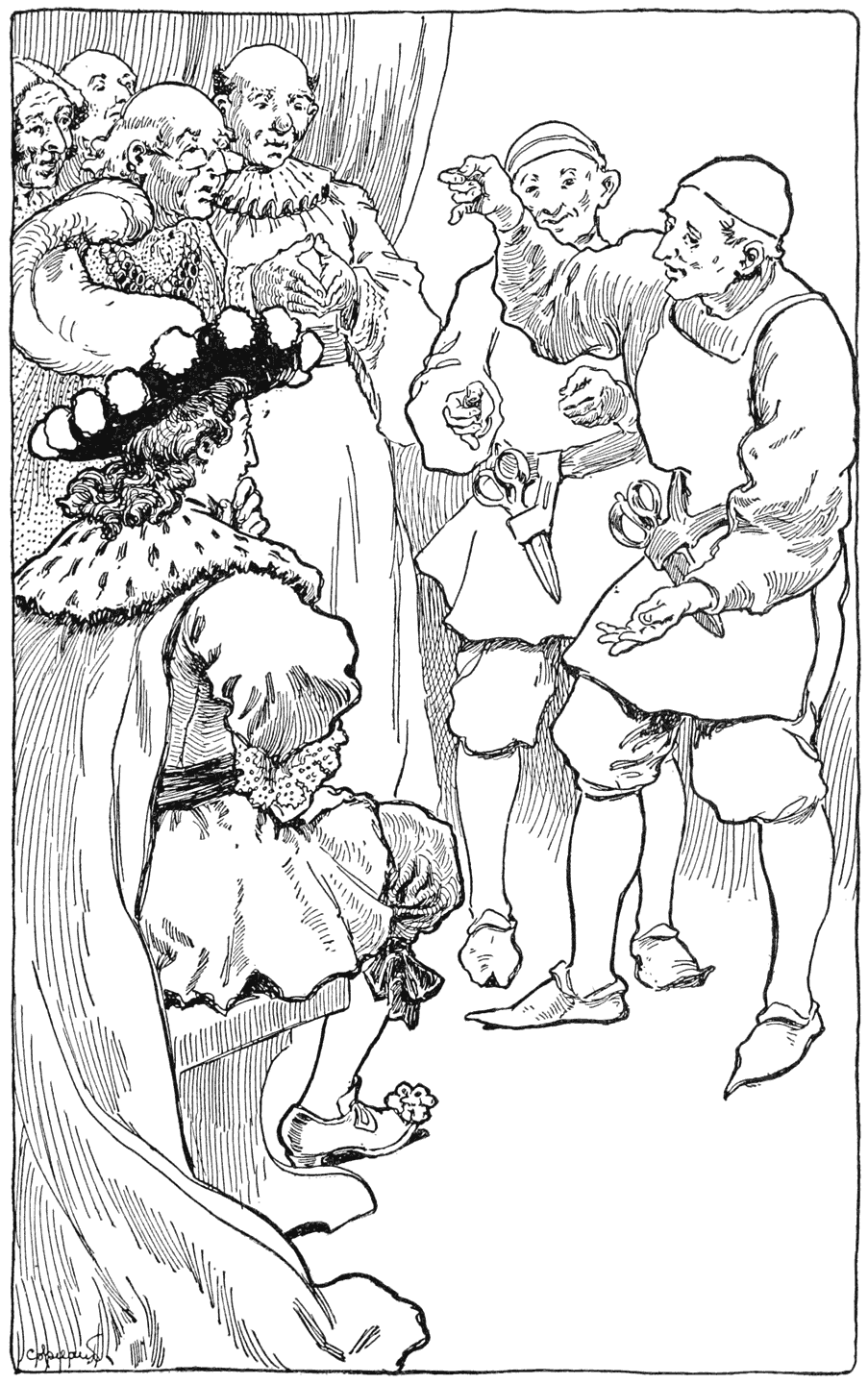

During the whole night before the day on which the procession was to take place, the rogues sat up and worked by the light of sixteen candles. The people could see that they were hard at work, finishing the Emperor’s new clothes. They pretended to take the cloth from the loom; they cut into the air with huge scissors; they stitched with needles with no thread; and at last they said, “Now the clothes are finished!”

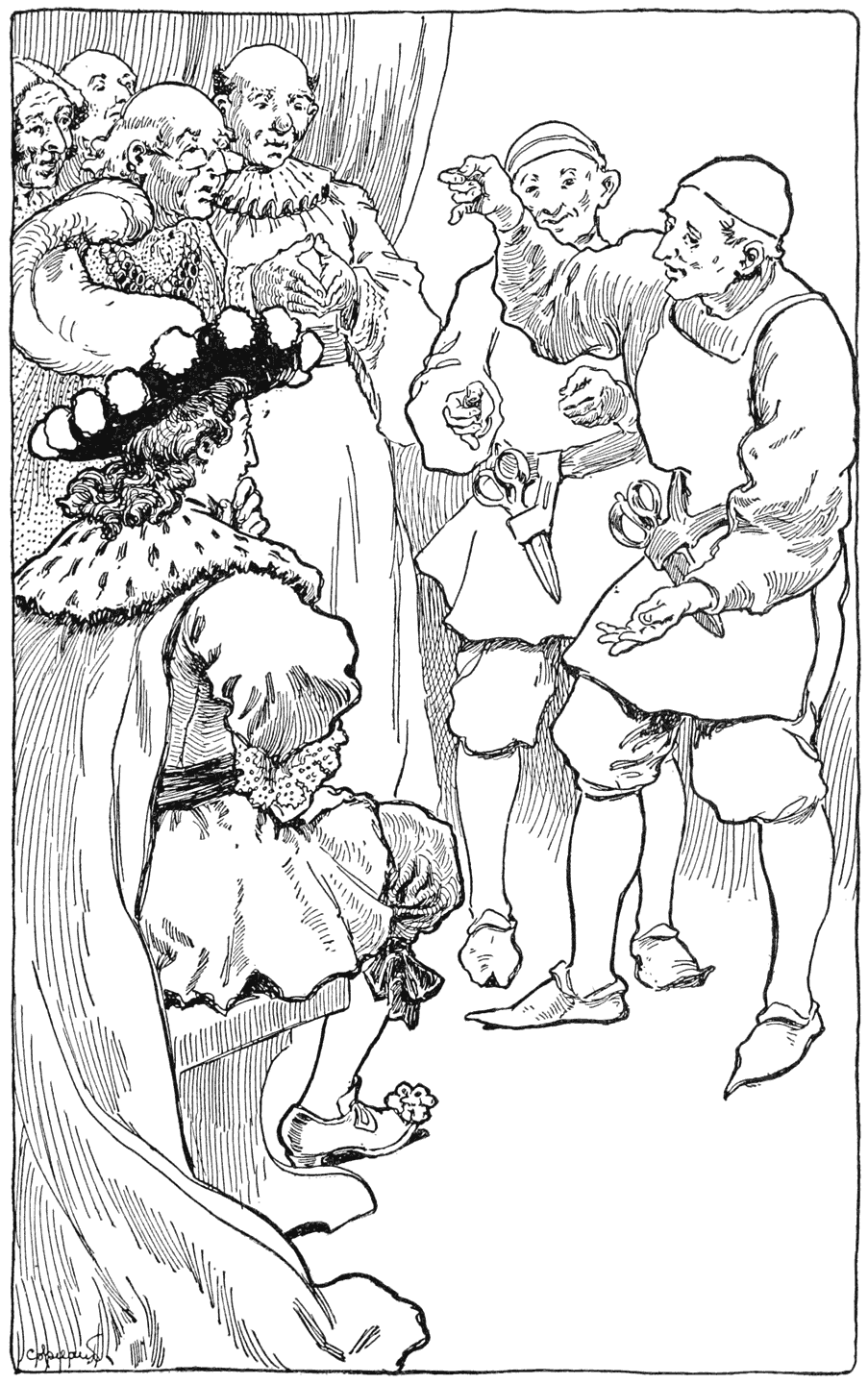

The Emperor came himself, with his noblest courtiers, and each rogue lifted his arm just as if he were holding something, and said, “See! here are the trousers! here is the coat! here is the cloak!” and so on.

“It is as light as a spider’s web. One would almost think one had nothing on; but that is the beauty of it!”

“Yes!” said all the courtiers, but they could see nothing, for there was nothing there.

“Will your Majesty be graciously pleased to take off your clothes,” said the rogues; “then we will put on the new clothes here before the great mirror.”

The Emperor took off his clothes, and the rogues pretended to put upon him one garment after another. The Emperor turned round and round in front of the mirror.

“How well they look! How beautifully they fit!” said everybody. “What material! and what colors! That is a splendid costume!”

“The canopy which is to be carried over your Majesty in the procession is waiting outside,” announced the master of ceremonies.

“Well, I am ready,” replied the Emperor. “Don’t the clothes look well?” and he turned round again in front of the mirror to appear as if he were admiring his costume.

The chamberlains who were to carry the train stooped and put their hands near the floor as if they were lifting it; then they pretended to be holding something in the air. They would not have it noticed that they could see nothing.

So the Emperor went along in the procession under the splendid canopy, and all the people in the streets and at the windows said: “How beautiful the Emperor’s new clothes are! That train is splendid! and how well they fit!”

No one wanted it to be noticed that he could see nothing, for in that case he would be unfit for his office, or else very stupid. None of the Emperor’s clothes had been such a success as these.

“But he has nothing on,” said a little child.

“Just hear the innocent!” said the father; and each one whispered to his neighbor what the child had said.

“But he has nothing on,” cried out all the people at last.

This struck the Emperor, for it seemed to him that they were right; but he thought to himself, “I must go through with the procession now.”

So he held himself stiffer than ever, and the chamberlains held on tightly, carrying the train which was not there at all.