CHAPTER VI

HOW FRANCIS MARION HEARD GOOD NEWS FROM WILLIAMSBURG

FOR weeks the little band pressed on through swamps and over stony roads. The Baron De Kalb, with a force of Continentals from Virginia, was marching south, and it was upon falling in with this army that Marion based his hope of safety. For it had not been long before the alarm was out; the swift, merciless dragoons of Tarleton and the skulking loyalists were after them night and day. How they escaped, they themselves could not afterward remember; the bay of dogs, upon their trail at night, would often startle them into renewed flight; the warning of a friend, or perhaps a slave, would cause them frequently to change their course by day.

Marion’s injured limb grew slowly better; at last he was able to dispense with the sling and ride in the usual fashion. After this they made much better progress and pushed northward rapidly. Mrs. Collins was left at a small town with some relatives; the band was augmented from time to time during this flight until at last it numbered some twenty hardened, bronzed men and boys, well-mounted, but poorly armed and clothed.

Tom and Cole were scouting one afternoon; it was dark when they rejoined their comrades, who had encamped on the banks of a small stream. Marion, almost entirely well now, sat by the camp-fire cleaning his pistols when Tom threw himself from his tired horse and approached him.

“What news on the scout, lad?” asked the commander.

“A change has been made in the force which we are anxious to meet,” replied the boy. “General Gates has superseded De Kalb and is pushing south by forced marches. It is his intention, I hear, to carry the war to the enemy instead of waiting for him to attack.”

Marion received the intelligence with moody brow.

“Gates,” said he, slowly. “I’ve heard of him. A hot-blooded, impetuous officer. Brave, but rash; and not at all the man for the work.”

“You, too, think he should avoid a meeting until compelled to fight, do you, major?”

“He should avoid a meeting until he knows his ground and is acquainted with the force before him. There is nothing to be gained by venturesome enterprises such as, I dare say, General Gates will attempt. It will but weaken him and unnerve his rank and file. De Kalb would have been a better man; he is accustomed to the warfare of petty European principalities, which is conducted with caution and no waste of men or supplies. I am sorry to hear this; the appointment of Gates was a mistake.”

The fears for the reckless courage of Gates expressed by Marion were only too well founded. That hot-tempered officer came plunging through North Carolina, full-tilt, with the ambition, seemingly, like Cæsar to write a dispatch announcing in the same breath the sight of and the conquest of the enemy.

The army commanded by General Gates, though small, was the best-equipped that the south had yet seen; they were well-clad in smart uniforms; their musket-barrels shone in the sun; their camp had all the neatness of a camp of trained soldiery; their artillery was heavy and capable of excellent service. Despite his rapid marches, Gates had the knack of keeping his men in good condition, and on the evening when Marion, with Tom Deering and Cole riding upon either side of him, and his nondescript band of woodsmen and fugitive militia at his heels, rode into it, the Continental camp was at its neatest and trimmest. The coonskin caps and wretched rags of the newcomers excited the jeers of the smart regular troops as their owners went down the road, between the line of camp-fires, toward the general’s tent.

“If this is the sort of reinforcement South Carolina has to offer us,” cried a big sergeant of Virginia foot, “we’ll have to do their share of the fighting, too.”

Tom Deering could not stand the laugh of contempt that greeted this, but reined up beside a company of the jeering infantry and allowed his comrades to trot by behind the unruffled Marion.

“If you men of Virginia go as far as we of Carolina for the cause,” said he, “you’ll go to the mouth of the British cannon, and a little further.”

“Well crowed, my bantam-cock,” laughed the big sergeant. “And how long have you been soldiering, may I ask?”

Tom’s eyes flashed as he faced the circle of laughing infantrymen who had gathered about him at the prospect of sport; their laughter angered him, for he felt that it was uncalled-for and unjust. So he swept the big sergeant scornfully with his eye.

“I was soldiering,” said he, “before you had pulled on that nice, clean uniform for the first time. I had served a gun at Fort Moultrie and been under fire in a score of other places, sergeant, while you were still driving bullocks in the Virginia hay-fields.”

It was a fact well known to his comrades that the sergeant had, up to this time, never smelled gun-powder in actual battle; and when Tom finished speaking a roar of laughter went, directed at the big man; and he reddened angrily, and bit at his huge mustache.

“Never judge a dog by the color of his fur,” said Tom, delighted to have turned the laugh upon the other. “And never judge a man by the coat upon his back. When you, sergeant, have raced through an enemy’s country—a country, too, full of swamps, thickets and almost impassable roads, for months, with bloodhounds upon your track by night and Tories with ropes ready in their hands searching for you by day, you will not look so trim and natty as you do now, and you will not be so ready to laugh.”

The troops of General Gates were a rough, good-humored lot; it required but a moment for them to catch the truth of the boy’s remarks; and with one accord, the sergeant included, they burst into a cheer for the sincerity and heartiness of which there could be no doubt. Tom’s eyes gleamed with satisfaction as he waved his cap in response, wheeled his horse and dashed after his comrades.

“There is good stuff in them, for all their readiness to jeer,” he muttered to himself. “And they are big, strong, willing looking fellows, too; and should render an excellent account of themselves.”

Marion’s men were halted in the road not far from the headquarters of General Gates. The latter and Marion were standing at the flap of the tent conversing earnestly. Beside the stalwart general of the Continentals Marion looked insignificant; and Gates, like his men, seemed to regard the partisan’s command as a rabble, the like of which clings to the skirts of every army. His face wore an amused smile, not unmixed with contempt. It is a fact that this officer was a vain man, of ostentatious habit and one whose judgment was very apt to be affected by parade and the external show of things.

“I am very thankful to you, Major Marion, for coming to put your company at my service,” said General Gates, patronizingly. “But, the fact is, I have no very great opinion of cavalry, and think I have but little need of it.”

Marion flushed with resentment at this; but controlled himself.

“This is a very thinly settled country, general,” returned he. “I should think that an active troop of horse would be very useful both in securing intelligence and in procuring supplies.”

Gates seemed somewhat impressed by this, and after some further conversation, invited Marion into his tent. The troop of swamp-riders dismounted and picketed their horses outside the camp, preparing to settle for the night. The very rags and poverty of this little band which was afterward to become so famous were but proofs of their integrity, could Gates but have seen it in that light. It was in defiance of the temptations and the power of the British that these men had taken the field, and had the leader of the Continentals been a wise man, he would have seen, even through their rags and destitution, the steady glow of patriotism; which enkindled throughout the state by this little, dark, unassuming officer, and Sumpter, and a few others of equal daring, was to blaze out, at last, in that perfect brightness which was to cause the invader to slink away, confounded.

That night and the two following Marion and his men spent in the camp of General Gates. In spite of the bad impression which his tattered command had made upon the general, Marion’s undoubted knowledge of the surrounding country was noted and made use of. But Tom could not bear the camp or its people and spent but little time there; for he and Cole were constantly scouting over the flats and through the woods, at his leader’s orders, in the hope of catching a view of the foe.

The town of Williamsburg was not a great many miles away, and upon the evening of the first day Tom and his faithful follower rode into the town to see what news there was to be had. The town was a hotbed of patriotism; the very name of King George was execrated there, and the boy was sure to be welcomed and to receive what tidings of the British the townspeople possessed. As it happened, a few weeks before this, a party of British and Tories had entered the place and plundered right and left; a few who resisted, and some others whom the Tories pointed out as rebels, were shot; then the marauders rode off with the warning to Williamsburg to improve in her loyalty to king and parliament or she would receive another visit.

The citizens gathered in angry crowds. “If,” said they, “we are to be set upon when we have not struck a blow against the crown, what worse can happen to us if we take up arms and fight like men should against tyranny.”

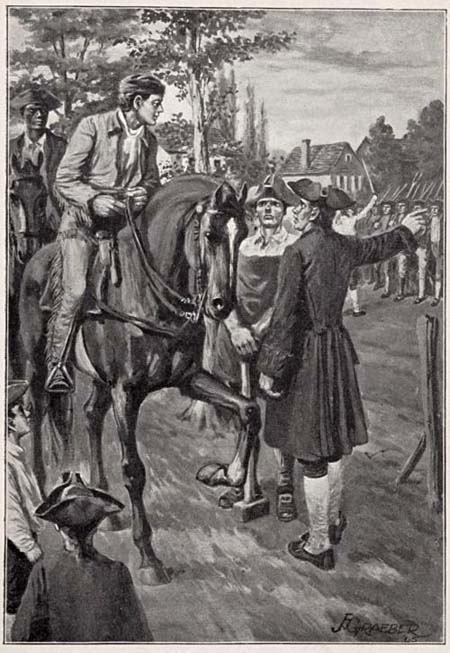

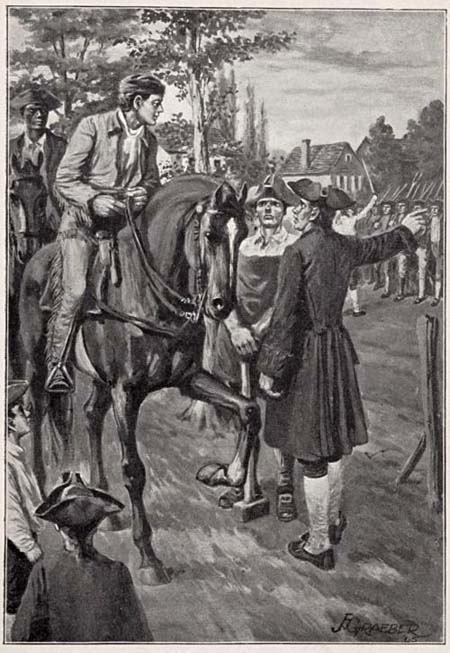

There was no answer to this argument, so the Williamsburgers proceeded to arm themselves with whatever they could find in the way of weapons, and set about drilling upon the village green. It was in the midst of the drill that Tom and Cole found them that evening when they rode down the main street, and very proud the townsfolk seemed to be of it.

“Tell General Gates,” said the stout old burgess to Tom, after finding out where he was from, “that the freemen of Williamsburg are preparing. Let the British make another of their ruffian raids upon the town, and it shall not be like the last. This time, instead of cautious words, they will be greeted by a sleet of lead.”

“Hurrah!” rang lustily from the ranks of the militia. “That they will!”

“Let them show so much as their noses in the town limits again and we’ll send them back to Cornwallis as soundly beaten as ever a pack of prowling curs were yet.”

The speaker was a brawny, sooty man, in a blacksmith’s apron; he carried a great sledge over his shoulder instead of a musket, and seemed in every way capable of doing his part in carrying out the promise. His words were greeted by much laughter and cheers by his comrades, and under cover of this Tom was drawn aside by the stout burgess.

“They are rare good lads, all of them,” spoke the burgess. “They will fight for their rights and their firesides to the last, but they have no one to lead them in whom they have confidence; it is a great pity, but it is so.”

“THEY ARE RARE GOOD LADS, ALL OF THEM,”

SPOKE THE BURGESS

He shook his head despondently as he said this, and as his eyes traveled along the not very trim ranks of the volunteers, he shook his gray head sadly.

“Is there no man of experience among them?” asked Tom.

“Not one, not one,” answered the burgess, “and it’s a great pity, for they are a fine body of men.”

He shook his head once more and sighed regretfully. Then turning to Tom he continued:

“I sent a messenger to Governor Rutledge asking him to select a leader for this company.”

“What was his answer?”

“He said that there was but one man in the entire South whom he would name as an ideal leader of irregular troops.”

“And that man was——?”

“One Francis Marion.”

Tom started in surprise and then laughed with pleasure.

“Well,” said he to the stout old burgess, “why do you not secure him?”

“He is not to be found. The governor has no idea if he be living or dead. Men die suddenly in these times, you know.”

“But suppose,” said the boy, “that I could tell you where to find him?”

The old man grasped him eagerly by the arm.

“You are not jesting?”

“Not in the least. I am of Major Marion’s command. He is now in the camp of General Gates.”

The burgess was overjoyed at this intelligence; he wrung Tom’s hand warmly. “Good news,” he cackled, hardly able to restrain himself. “I will go to him in the morning—I will offer him the command.” Then he paused suddenly and continued in a more sober tone. “Do you think, my lad, that he will be inclined to accept?”

Tom thought of his commander’s cold reception at the hands of General Gates, and answered promptly:

“I rather think he will, sir.”

“Good—good!” The old fellow went off, at this point, into a rapture of chuckling. “Come, you will lodge with me to-night; I will not accept a refusal. Wait until I give word to dismiss the company for the day; then you shall have as fine a supper and as soft a bed as you have ever had in your life.”

At the burgess’ command the drill-sergeant dismissed the militia; then Tom and Cole were led away to the comfortable stone house of the town official; their horses were put up in the stable and baited with corn; Cole was taken in hand by some of the negro servants, while his young master was borne off to be introduced to the family of the burgess. In spite of his worn clothes and unkempt appearance, the boy was kindly welcomed by his hostess and her blooming daughters. To be sure he noticed, now and then, that the girls would giggle together, aside, over his deerskin hunting-shirt or his leather leggings; but they made up for this by their many little kindnesses; and the sly looks of admiration which they stole at his handsome, sun-browned face and tall, sinewy form often made his cheeks burn.

The burgess was as good as his word; the supper which Tom sat down to was the best he had eaten for many a long week; and the bed upon which he stretched his tired length afterward, being the first he had slept in since leaving home, felt fully up to specifications.

Early in the morning the household was astir; and when Tom and the master of the house had breakfasted they bid the ladies good-bye. The chestnut and the bay were ready saddled at the door; and beside them stood a fat, white horse which was to bear the weight of the worthy burgess.

“He is not very speedy,” admitted the official, “but he is strong and safe. And that last quality, young sir, is not a thing to be overlooked when one comes to my age, and attains my girth.”

The ladies waved their kerchiefs from the windows; the burgess and the young swamp-rider took off their caps and bowed in return, while Cole grinned like an amiable Goliath. Then they shook their reins, and set off for the Continental camp, to bear the good tidings to Marion.