CHAPTER IX

HOW TOM DEERING HELD THE STAIRCASE

THE dining-room of the Foster mansion presented an appearance of great confusion, and Tom looked about in astonishment. The furniture was thrown about in much disorder; some of the costly pictures had been torn from the walls; others hung askew; valuable bric-à-brac was shattered upon the hearth.

“What has been going on here, Dogberry?” asked the young swamp-rider.

“Didn’t I told you, Mars Tom, dat dose gemmen was carrying on scand’lus. Just take a look around and see if I ain’t right.”

At this moment a thin, white-faced man entered the apartment; he had the appearance of an invalid, and seemed very much disturbed. At sight of the boy he started back, with a cry.

“You here!” he exclaimed, astonished.

“Yes, Mr. Foster,” quietly, “I am here. Pardon my entering without being asked; but your Tory visitors became a trifle too pressing outside there.”

“Oh,” cried Mr. Foster, “when shall I rid myself of them! See what they have done,” with a gesture of one thin hand at the ruin of his precious objects of art; “wanton vandalism—without a shadow of excuse.”

“The cowards!” broke out Tom, angrily.

“They demanded wine,” said Mr. Foster, “well knowing that I never keep it in the house; and because I was unable to produce it for their entertainment they proceeded to destroy whatever their hands fell upon.”

“It’s a shame,” cried Tom, his voice full of honest indignation at the outrage and sincere pity for the frail, white-faced man who could not resent the wrong done him. “But we’ll see what we can do for these gentry before the day is over.”

“Your cousin, Mark Harwood, is their leader,” said Mr. Foster.

Tom reddened with shame at the words. “Mr. Foster,” said he, “he is a sort of cousin of mine, it is true; but not a single drop of the Deering blood flows in his veins.”

“Forgive me,” cried Mr. Foster. “I had not intended, my boy, to make you remember a relationship that must be painful to you at all times. But,” looking hurriedly about, “we must not forget that you are in a position of no little peril. If the Tories were to return and find you here——”

“Dey am returning, Mars Foster!” exclaimed Dogberry, who had left the apartment as Mr. Foster entered, and now came posting back, his black face shining with excitement. “Dey’s all on de veranda now, sah.”

Tom glanced swiftly toward the window.

“No, no,” cried Mr. Foster, “not that; they may be watching for you there.”

“I must get cover of some kind,” said Tom. “Do you not hear their footsteps? I shall be caught like a rat in a trap!” His glance traveled rapidly about the room. “Have you not a cupboard or some such thing in which I can conceal myself?”

“No,” said Mr. Foster, in despair. But suddenly his face lighted up. “I have it; the very thing.”

Grasping Tom by the arm he threw open a door. The boy found himself in a wide hallway at the end of which was a broad steep flight of stairs leading to the floor above. Almost at the foot of the staircase was a large clock whose wooden works made a burring sound as they moved, and whose great pendulum ticked loudly, slowly, solemnly. The clock almost reached from floor to ceiling: Mr. Foster threw open the painted glass door.

“There is room for you there,” said he.

In a moment Tom was inside the big clock with the door closed upon him; almost at the same moment the outer door opened, and the Tories came stamping noisily into the hall.

“I don’t believe there is any one about the place except those who belong here,” said one of them in a loud voice.

“I tell you I heard a strange voice,” insisted Mark Harwood.

“Bah!” The owner of the big voice was a huge man, with massive limbs and the torso of a giant. As he came down the hall he grumbled, “How long are you going to keep us at this place, anyhow; let’s put the torch to it and be off.”

“Plenty of time for that,” said Mark. “Don’t be in a hurry.”

“Hurry,” growled the big man. “We’ve been here,” he drew out a heavy gold watch, “almost three hours,” he continued, consulting the timepiece.

“Oh, your watch is wrong!”

“Wrong! This watch is never wrong. But, hold on, let’s compare it with Master Foster’s clock.”

Tom held his breath as the speaker paused before the clock.

“Hello, the confounded thing has stopped,” said the big man. “Run down, I suppose. Wait, gentlemen; I’ll do Foster a favor by opening his clock and winding it up.”

He had his hand upon the catch of the clock door when Mark Harwood pulled him away.

“Never mind the clock,” said the latter; “let us attend to more important matters.”

Mr. Foster had re-entered the dining-room as soon as Tom had hidden himself in the clock case; therefore he neither saw nor heard what passed in the hall. The Tories came into the room, their swords clanking and their spurs jingling.

“It’s a good thing for you, Foster,” growled the huge man, whose name, by the way, was Clarage—a notorious bully and leader of a body of Major Gainey’s loyalists—“that we did not find any one lurking about the grounds.”

“You could not have done much worse than you have already done,” said Mr. Foster, bitterly.

“So you think,” put in Mark Harwood. “But we would have proven you wrong without loss of time, my dear sir; mind you that.”

“A long rope and a stout limb for the spy,” laughed Clarage; “and not to be any way mean, Foster, we would have given you a place beside him.”

Lucy Foster came in at that moment, and her eyes filled with renewed resentment as she heard these words addressed to her invalid father.

“How long, Mr. Clarage,” she asked, “is this to continue? My father is not strong, as you well know; your ruffianly behavior is making him ill!”

“Ah, it is the little rebel,” laughed Clarage, in his bull-like tones. Then he turned to Mark Harwood. “Do you know, Harwood, who she reminds me of as she stands there with her eyes flashing and her little hands clinched? Why, that cousin of yours—Laura, you know. Why man, it seems to me that all the prettiest girls in the colony are rebels.”

“But Laura will not remain one for any great length of time,” said Mark. “And neither would Miss Lucy, here, for all her angry looks, under like conditions.”

“Why, how is that?”

“Laura is to be married,” returned Mark.

Tom Deering, in the tall clock, started.

“Married, eh?” said Clarage. “And when, pray?”

“On next Christmas eve.”

“And to whom?”

“To Lieutenant Cheyne, of Tarleton’s horse.”

Laura married! and to the inhuman monster who had tortured poor Cole! Tom could not, would not believe it!

“I did not fancy she’d consent to wed a king’s officer,” said one of the Tory band. “She was always a proud little thing—a very spitfire.”

“Oh, she’ll consent fast enough,” laughed Mark. “She refused Cheyne, point-blank, when my father proposed the match; but before Christmas day comes around, she’ll have changed her mind, I’ll promise you that. My father is not a man to be balked in his purpose by a slip of a girl.”

“Why did he select Cheyne as her husband?” asked Clarage, with interest. “Come, tell us that; I’ll warrant there’s some good reason for it.”

“There is a good reason for everything that Jasper Harwood does,” said the Tory who had before spoken.

“You are right in that,” said Mark. “You see, father is very anxious that the estate of our rebel relative, Deering, who was taken in arms against the king, shall not revert to the crown.”

“Very good of him,” said some one. “But it is the first time that I knew him to have any friendly feeling toward Deering.”

“He has none. It is not for Deering’s sake that my father is anxious, but for his own. You see, he wants the estate for himself.”

A gale of laughter went up at this confession. Lucy had been urging her father to go to his chamber, as his face was growing more drawn and haggard every moment, showing that the strain was greater than he cared to admit. At last he consented; she opened the door leading into the hall and he passed out, thinking that Lucy was following him. He paused at the tall clock to speak an encouraging word to the boy concealed therein, then looked surprisedly about for Lucy.

“She has gone on up to her room without waiting for me,” said he, to himself. Then with another “courage, my lad,” to Tom, he ascended the staircase.

In the meantime Mark Harwood was explaining, with evident delight, his father’s reasons for marrying Laura to the British dragoon.

“Cheyne,” said he, “has some very high-class connections across the water; an uncle is the Duke of Shropshire, you know, and the Marquis of Dorking is a cousin. Both of these gentlemen are very friendly with the king and Lord North; so, you see, with the lieutenant in the family, there is no great danger of our losing the Deering estate.”

Another shout of laughter greeted this; the crafty methods of Jasper Harwood seemed to please the Tories greatly. Suddenly there came a loud bellowing from Clarage, and the laughter ceased.

“Where has Foster gone?” demanded the Tory. “What has become of him? He was here a moment ago.”

“He’s up to some trick,” cried Mark Harwood excitedly. “There is a Whig spy about, somewhere; and Foster has gone to warn and help him to elude us.”

There was an instant rush for the door; but Lucy Foster stood there barring their passage.

“My father is unwell,” she said, quietly, but with a slight tremble in her voice. “He has gone to his chamber to rest.”

“Ah, is it so, indeed,” sneered young Harwood. “Well, we will assure ourselves of that, Miss Lucy, if you please. Stand aside.”

“I will not!” cried she, defiantly.

“Don’t waste words with her,” growled Clarage. “There is no knowing what her rebel father is up to while we are parleying with her, here.”

“I shall not move!” exclaimed Lucy, in ringing tones. “My father has gone to his chamber because he is unwell—I give you my word for that. Is it not enough?”

“No,” said Harwood. “We’ll see for ourselves.”

“You shall not disturb him. It is cruel—it is a sin—for he is weak and ill.”

Without any further words the Tories sprang at her. But at that same instant the door, against which the brave girl had placed her back, opened behind her; a strong arm drew her quickly into the hall; then the door closed with a snap and the astounded king’s men found themselves facing, not a weak girl, but a tall, muscular youth with a keen bronzed face, steady, cool eyes, and a naked sabre in his hand.

“Gentlemen,” said he, his fearless gaze traveling over them as he stood there, “I bid you good-day.”

“Tom Deering,” cried Mark Harwood, astounded.

“Quite so!” The young swamp-rider’s eyes were filled with scorn as he addressed himself to his Tory cousin. “You are surprised to see me, I take it.”

“Who is this fool that places his head in the lion’s mouth?” roared Clarage, his deep voice sounding like the rumbling of distant thunder.

“Don’t flatter yourself.” Tom’s level gaze met Clarage’s furious one, with quiet assurance. “There are no lions here; it is more like a nest of rats.”

With a snarl the big Tory dragged his heavy, brass hilted sword from its scabbard.

“Then feel of the rat’s teeth,” he growled drawing back his arm for a tremendous blow.

“It’s the scout of the Swamp-Fox,” cried Mark Harwood. “Cut him down.”

Tom smiled at the eagerness in his cousin’s voice, and at his very evident disinclination to try to put the words into execution upon his own account. The careful teaching of Victor St. Mar had not been forgotten; on the contrary, Tom had not ceased to practice with small sword and sabre each day of his life; until, at last, there was not a man in Marion’s brigade that could stand before him sword in hand.

This gave him a feeling of confidence when Clarage drew back his heavy blade to cut him down, as Mark Harwood had cried out for him to do. The Tory had great strength, it was true, but the lad’s practiced eye told him that there was absolutely no skill behind it.

“Now, my jackanapes,” bellowed Clarage, “I’ll nail you against the door!”

The heavy blade cut downward with a swish. But it was met and deftly turned aside; and the wielder of it received a sharp, contemptuous rap upon the side of the head from the flat of the boy’s sabre, in return.

“Rats!” rang out Tom’s voice. “Rats, all of you! Insulters of girls and bullies of old men! You dare not face one who rides with Marion. I defy you all!”

For, at this exhibition of his dexterity with the blade which he held in his hand, the Tories had ceased to display any undue eagerness to come forward. Clarage, indeed, made well nigh mad with rage, strove to get in a cut; but the flashing sabre of the swamp-rider drove him back with ease.

“Pistols,” cried one. “At him with the pistols.”

“They are in the holsters in the stable,” returned another. This was a fact that had been noted by Tom; the total absence of firearms among the Tories was the reason for his, seemingly, uncalled-for boldness.

“Are we to let one boy hold us at bay,” shouted Clarage, flecks of white foam appearing upon his lip, so great was his rage. “At him, all together! Cut him down!”

A circle of drawn swords flashed in Tom’s eyes; but before they could strike, he had vanished through the door and clapped it in their faces.

“After him,” bawled Clarage, in a hoarse, thick voice, as he tore the door open and dashed into the hall. “Don’t let him escape.”

“Don’t trouble yourself, my dear sirs,” came a steady, resolute voice from above. In amaze they glared upward. About midway on the staircase stood the bold youth who had so braved their wrath, his sabre point resting upon the step upon which he stood. “I have not the slightest intention of escaping; your company is too entertaining for me to desire to leave you.”

“We have him safely,” said Mark Harwood in tones of triumph. “Escape is impossible now; get the muskets, Fannin,” to one of the others, “we’ll soon bring him to his knees.”

The man shot quickly down the hall and out at the front door. Tom’s laugh rang in the ears of the seven who remained, for he was thinking of the disappointment that was in store for them.

“He must be mad,” growled Clarage at this. “No sane person would laugh at the prospect of certain death.”

“Right,” said Tom. “You are always right, except when you imagine you can handle a sword.”

Once more his laugh rang out; and before he had done, the man sent for the firearms came racing back.

“The rifles are gone,” he announced.

“Gone!” they stared at him in consternation. “What do you mean, Fannin?”

“Just what I say,” returned the Tory. “The rifles have been carried off.”

“I have taken good care of that,” cried the lad on the staircase. “Your rifles, gentlemen, are where you will not be able to find them in a hurry. If you want to take me it must be hand to hand.”

“Then hand to hand it shall be,” roared Clarage, his face purple with passion. “Shall it be said,” he cried, turning to his companions, “that one rebel boy held back and defied eight loyal subjects of the king?”

His was the boldest spirit among them, and now its influence began to be felt.

“No! No!” they shouted.

“Then at him, like men. I only ask you to follow me.”

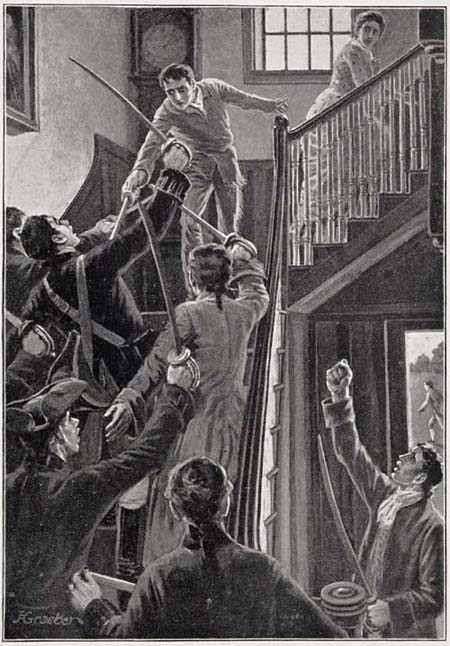

They took tighter grips upon the hilts of their swords. There was a window at the head of the staircase and a landing just under it. A broad beam of sunlight streamed through the window and bathed the staircase and the boy upon it in a flood of golden light. As the Tories brandished their swords for the rush, Tom heard a slight sound behind him; turning his head a little he saw Lucy Foster, pale faced and with clasped hands, standing upon the landing near the window.

“Don’t come any farther, if you value your safety and mine, also,” he had just time to call to her, and then the Tories were upon him. Clarage was first; he delivered a mighty cut at Tom’s head, but it was put aside and the young swamp-rider’s blade bit deeply into his right shoulder. Clarage uttered a roar of rage; his right arm was helpless, but he transferred his sword to his left and came on again. At each side of Clarage and over his shoulder the other Tories were cutting and thrusting desperately at Tom. The blows came swiftly and frequently; but his blade met them all, darting here and there like a streak of light and seeming at times to twine about their own like the coils of a metallic snake.

Desperately the battle waged on their part and gallantly upon his; the girl behind him, upon the landing, more than once cried out in fear as she saw almost certain death threatening the youth from the Tories’ sword points; but each time he redoubled his exertions and swept the staircase clear of his foes.

However, this could not last; he was but human, and his strength at last began to fail; two of his assailants were lying, disabled, at the foot of the stairs, and the others, to a man, bore testimony to his prowess. But, when they saw his strength waning, under the urging of Mark Harwood they pressed upon him, dealing showers of blows with their heavy sabres.

“Surrender,” cried Mark Harwood.

“You’ll take me, if you get me at all,” panted Tom, dealing an ugly cut at the nearest Tory.

“Then take you we will,” shouted the bull voice of Clarage. “Press on, men; he cannot strike so swiftly now. Press on and we have him.”

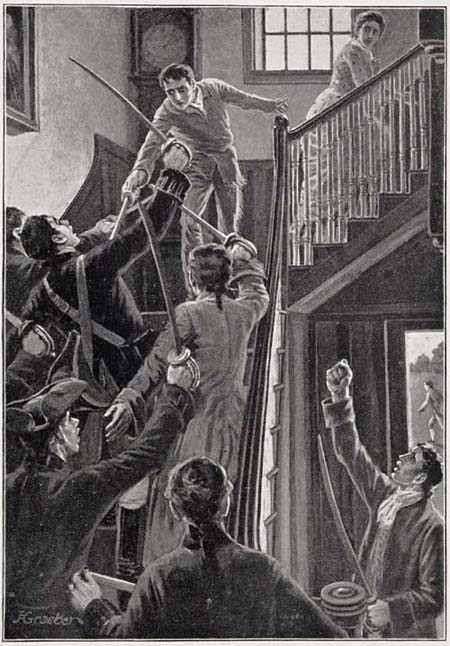

They crowded upon him with loud shouts and whirling swords. Step by step he was beaten back, breathless, exhausted, but fighting on. And when the moment came when he must be taken or cut down, there was a sudden crashing sound from behind him; the glass of the window at the landing was splintered and the frame was dashed in upon the floor. The lad’s heart sank, for he fancied it must be some of the enemy come to take him in the rear. He dared not turn his head to see, for the blows were showering about him; but, then, his heart gave a great bound of joy as a strange, weird cry sounded in his ears and the giant form of Cole sprang through the shattered window and stood towering and glaring beside him.

But, as it chanced, the colossal slave was weaponless. Mighty as was his strength he could not pit his naked hands against the Tories’ swords. At the turn of the staircase, on the landing, a thick oaken post, carved and about the height of a fair-sized man stood, supporting the stair-rail.

STEP BY STEP HE WAS

BEATEN BACK

With a bound he had reached it; with a mighty wrench he tore it from its place; and, waving this massive weapon as lightly as a child would a sword of lath, he flung himself into the fight.

Tom was about striking his last weak blow, as the Tories saw clearly. But before the terrific onslaught of the giant they recoiled, amazed; the huge club wheeled about his head once, twice, thrice and they were swept, howling, to the bottom of the stairs.

“Brave Cole!” Tom gasped the words as he sank back upon the stairs, exhausted. “Strike hard; it’s our lives or theirs.”

At that time one of the party discovered Mr. Foster’s arms chest; the Tories threw themselves upon it with shouts of delight and in another moment a blazing volley swept up the staircase, the bullets singing spitefully past Cole’s ears.

“Back,” cried Tom. “Back, Cole.”

They bounded round the turn in the stairs, Tom bearing the frightened girl with him. Another volley crashed into the wall, behind where they had just stood.

“They will be upon us in a moment,” said Tom, his face pale, but his eyes burning with a resolute light. “Miss Lucy, leave us; we cannot hope to hold them back, now; you will be in danger.”

The Tories were reloading in the hall; Clarage was roaring in furious delight and stamping about like an enraged lion. Cole was rapidly telling Tom all about what had been done at the barn, his fingers flying like mad.

“They are ours now,” stormed Clarage, in loud triumph. “We’ll make them beg; the rebels, the dogs—we’ll show them what king’s men can do.”

“It’s high time you were doing it.” Tom bent over the broken rail at the place from where Cole had torn his mighty club. “It seems to me, the loyal subjects of the king have performed rather badly to-day.”

“But we’ll do better from now on,” laughed Clarage, who had in the height of their triumph actually begun to grow good-humored. “Are you ready, gentlemen?” to the others.

“Yes, yes,” came a chorus.

To the astonishment of all, Tom Deering stepped boldly forward into plain view; he was without weapons, and Clarage, with a roar of laughter, at once jumped to the conclusion that he meant to surrender.

“He has weakened,” he yelled. “The rebel has weakened.”

“Shoot him down,” cried Mark Harwood, from well in the rear. “No quarter!”

Tom held up his hand, quietly; he showed not the slightest trace of fear, for the things that Cole had made him understand had filled him with confidence. The Tories below gazed up at him in astonishment. Tom spoke:

“I charge all men within hearing of my voice to lay down their arms, in peace. You are enemies to your neighbors and to Carolina, and in the name of the Continental Congress, I call upon you to surrender.”

“He’s mad!” burst out Clarage, “as mad as a March hare!”

“Down with him,” shrilled the voice of Mark Harwood. “No quarter to the rebel.”

The muskets were about to be raised to their owners’ shoulders; Tom’s voice rang out warningly.

“On your lives, lay down your arms.”

A shout of derision greeted the words; then the young swamp-rider’s fingers went to his lips and a sharp, shrill whistle split the air. It was the signal that Cole had arranged with the released prisoners; and like magic it was answered. Through every door and window, it seemed, sprang a resolute man; before the Tories could raise a hand a shattering volley was poured into them. A cloud of smoke, cries and the sound of heavy blows were swept up the staircase; Lucy, her hand pressed to her wildly-beating heart, made as though to look over the rail at the awful scene below. But Tom put her aside, almost roughly.

“Don’t look,” said he. “There is nothing there for you to see.”

The words were scarcely out of his mouth when the door below opened with a crash; shouts and cries were heard upon the veranda and lawn. Tom rushed to a window and looked out. He was just in time to see Mark Harwood, Clarage and the other surviving Tories rush toward the barn, spring upon the backs of the horses which the liberated prisoners had brought out for their own use, and gallop swiftly away.