CHAPTER XII

HOW TOM TOOK PART IN A MYSTERIOUS CONSULTATION

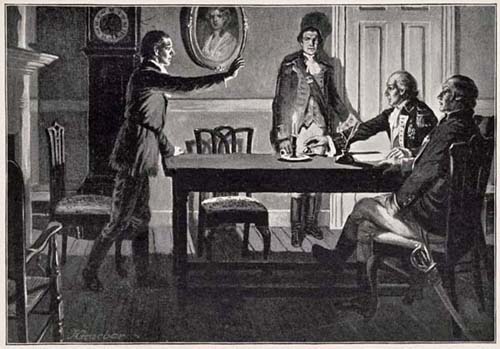

FOR a moment Tom Deering was rendered powerless by the sudden shock of the surprise; he stood staring at the two British officers with wide-open eyes. Then a feeling of helplessness swept over him—a sense of being caught—of having been lured into the clutches of his foes. He could not speak; at each tick of the clock he expected to hear them denounce him.

But they did not; they bowed to him silently and advanced to the table at the centre of the room and sat down; Tarleton was looking straight at him, but gave not the slightest sign of having recognized him; Cornwallis had taken up a quill from the table, and was tapping with it upon the table, a flickering smile upon his face.

“You seemed rather disturbed,” said he.

With a powerful effort Tom pulled himself together; he was caught, but there was no use in his showing the white feather, he thought. So he replied, quietly enough:

“I must confess to being slightly surprised, sir. But that is all.”

Cornwallis’ smile broadened.

“Just so,” chuckled he. “You did not expect to meet two British officers, I suppose.”

“I had no idea whom I was to meet,” said the young swamp-rider.

“Of course not; how could you?”

Cornwallis tapped the table with the point of the quill, thoughtfully; now and then his eyes would wander from Tom’s face to that of Tarleton; he seemed to be considering something very carefully.

“I had thought,” said he at last, “to meet a very different person.”

“A rather older person, to be sure,” said Tarleton.

Tom bent his head slightly, but said nothing.

“Of course,” said the commander of the British army, “you do not know either of us—no more than we know you. It is better so; the work that you are about to do is of exceeding peril, and the less we know of each other, the better.”

Tom looked at the speaker in astonishment. However, he did not allow the feeling to show in his face; they were playing with him, he fancied; and he suddenly resolved that he would bear his part in it, and prove that he was not afraid.

“I had thought,” said he coolly, after a moment’s silence, “that I had met this gentleman,” nodding toward Tarleton, “before.”

“You have just come to Charleston, from Canada,” said Tarleton. “How could you?”

The expression upon the man’s face as he said this, puzzled Tom; he seemed to be sincere; he seemed to mean it; and not the slightest recollection of having met Tom in a hand to hand conflict that day in the swamps was observable in his countenance. What could it all mean? The lad began to doubt the evidence of his own senses.

“How,” asked Lord Cornwallis, “is Sir Henry?”

“Sir Henry?” Tom looked at him dully.

“Of course, Sir Henry Clinton.”

Tom recovered, with a slight gasp.

“Oh,” said he, “he was quite well when last I heard of him.”

“Then,” said Cornwallis, “he does not write to you very often.”

“No,” confessed the lad, “he does not.”

“I had thought that he would neglect it after a time. He has a short memory at best. However, since you have arrived here safely it does not matter.”

“You received the list of names which we sent you?” inquired Tarleton.

“I did,” answered Tom, his mind going at once to the papers which he had received, but had not understood.

“You did not get much information from them, of course,” put in Cornwallis, with a laugh. “But that was not to be expected; you must become acquainted with the section first.”

The truth was slowly dawning upon the young scout; these men were not playing with him as he had supposed. They were serious; they had mistaken him for another—for a person whom they had never seen, and who was due in Charleston, upon some mysterious errand, at that time.

“This department of yours,” said Tarleton after a longer pause than usual, “is something new, is it not? I have heard that Chatham was strongly opposed to it, but that the king——”

“Hush!” Cornwallis laid his hand warningly upon the other’s arm. “That is a thing not to be spoken of.”

“Oh!” exclaimed Tarleton, impatiently, “among friends——”

“Even among friends,” said Cornwallis, “silence must be kept.” He turned to Tom. “Is this not so?”

“I believe,” answered Tom slowly, for he feared to betray himself, “that the utmost secrecy is considered necessary.”

“Exactly.” Cornwallis looked triumphantly at the other officer. “Just what I have always held since the matter was first brought to my attention. To hope to do anything by such means, one must work in the dark, so to speak—one must not allow even a whisper to reach the upper world, if success is to be hoped for.”

“Quite right,” and Tom bowed, more mystified than ever, but determined to carry out the matter to the end.

“And now,” said Cornwallis, “I suppose you will wish to see the gentleman who is to give you the information which you seek.”

“If you please.” The youth said this not without some misgiving; but he dreaded to refuse, as it might excite some suspicion.

“Ah,” said Cornwallis, apparently greatly pleased. “I had fancied that you’d not want to see him until later. But I had him come here to-night on the chance; I am delighted that you show a willingness to take the matter up so promptly.”

Tom was rather angry with himself for this same willingness; but it was too late now; so Cornwallis rang a bell to summon the person spoken of.

“He is waiting in the next room,” said he, “and I rather think you will find him the kind of man you want.”

Here the door opened and Lieutenant Cheyne of Tarleton’s horse entered. He looked at Tom sharply for a moment as he crossed to the table at which the others were sitting. But it had been four long years since the affair of the mansion of Jasper Harwood, and Tom had greatly changed and grown since then; so he bore himself with boldness and confidence and looked straight into Cheyne’s eye without a quaver. The lieutenant, however, was only marveling at the youth of the visitor who had come there wrapped about in so much mystery; no thought of ever having met him before had crossed his mind.

“This gentleman,” said Cornwallis, “will introduce you wherever you wish, in Charleston.”

The lieutenant bowed.

“I shall be most happy,” said he.

“As to the towns and cities further north,” proceeded Cornwallis, “we have provided another person for that. I will summon him, also.”

His hand was already upon the bell, but Tom stopped him.

“One moment,” said he. “The name of this person, if you please.”

The other three looked at him in surprise.

“I had thought that no names were to be mentioned at this stage of the proceedings.”

“THIS GENTLEMAN,” SAID CORNWALLIS,

“WILL INTRODUCE YOU”

Tom saw that he had gone a little too far; but he feared possible recognition, and it might chance that the man whom the British commander was about to call in, would know him; so he continued, boldly:

“Safety is the first thing to be looked after. I must demand the name of this person, before you admit him.”

“Surely you can suspect no one in Charleston,” said Cornwallis in surprise.

Tom determined upon a shrewd stroke.

“If none were suspected,” said he, “I should not be here.”

The words struck home; the three British officers looked at each other.

“True,” said Cornwallis, soberly. “That fact escaped me for the moment. The gentleman who is waiting without is Mr. Clarage, a loyal subject of the king.”

Without knowing it the young swamp-rider had been standing upon the brink of discovery; for had Clarage once entered the room he would have been sure to have recognized him. The look upon Tom’s face was observed by Tarleton, and misconstrued.

“Surely,” said he, “you do not mean to say that you refuse Clarage’s aid!”

“I do,” said the youth, promptly.

“You suspect him!” Cornwallis uttered the words in tones of the utmost astonishment. “Why, I did not dream that you ever had heard his name before.”

“I have heard of the gentleman many times,” said Tom, gravely.

Once more the three officers stared at one another, this time apparently astounded.

“I had not imagined,” said Lieutenant-Colonel Tarleton, “that the ramifications of the new system were so extensive.”

There was a certain note of respect in his voice that did not escape Tom; he had made an impression by his boldness.

“There are many things connected with this business,” said the youth, “that I don’t understand myself.”

“I suppose not—I suppose not.” There was awe in the voice of Cornwallis as he said this; and Tom could scarcely keep from laughing. He was determined to escape the notice of Clarage, so he continued,

“This man Clarage must not be permitted to observe me—he must not see me—he must not know who I am.”

“Is it possible that he is suspected as strongly as all that!”

“He is not a king’s officer,” said Tom, “and in these times it behooves us to suspect every one not actually in the uniform.”

“Right,” cried Tarleton. “Right, sir! Allow me to shake you by the hand.” He grasped Tom’s hand as he spoke, and shook it warmly. “When I first clapped eyes upon you I could not understand why a boy had been sent about this important business; but I see it now; it’s because you have brains and know how to use them.” He continued to shake Tom’s hand violently. “I beg your pardon, sir, for my first impression of you; but I see my mistake, and am willing to acknowledge it. You are right. Every one in Carolina should be suspected except those who wear the king’s uniform.”

Then the two senior officers talked long and earnestly about matters of which Tom had not the slightest knowledge; but, seeing that he was supposed to be well informed as to most of it, he kept nodding his head or shaking it, as the case might be, and wore a look of great gravity. He gradually drew from their talk that he was supposed to be a messenger, sent by the very highest officials of the government at London, to collect facts of some kind. But just what the facts were, and why so much caution was considered necessary in their collecting, he could not learn. At length Cornwallis said:

“There is to be an affair to-morrow evening at which you could meet a very great many people, if you choose to attend.”

Tom trembled with expectation; but his voice was steady enough, as he asked:

“Indeed; and what is that?”

“Lieutenant Cheyne’s wedding; it is Christmas eve and he is to marry the ward of Jasper Harwood, a most excellent gentleman and a strong advocate of the king’s government.”

“I shall be most happy to have you come,” said Cheyne, bowing.

“I’ll be glad to,” said Tom, returning the bow, and struggling to hide his eagerness.

“There is to be a sort of Christmas fête at the same time,” remarked Lieutenant Cheyne. “A mask, you know; it’s a thing that the people here do about Christmas time, you see.”

“Ah, yes! A mask.” Tom looked thoughtful. “But, my dear sir, I think this will prevent my attending. I have no costume.”

“No costume,” broke in Tarleton, with a loud laugh. “What is the matter with the disguise you are wearing now?”

“Ah, true,” said the youth, coolly. “Quite so.”

“I’ve had my eye upon it for some time,” said Tarleton. “It’s much the same sort of thing as that scamp Marion and his fellows wear. But I suppose you adopted it because you had to pass through the region which that villain infests.”

“I did pass through Marion’s district—yes,” said the youth, evenly.

“It will do nicely,” said Cheyne. “Indeed I could imagine nothing better for such an occasion.”

“Very well, then,” said Tom. “It is settled.”

“I shall be glad to send for you,” remarked Cheyne.

Tom considered for a moment. His thoughts were working upon a plan that had just flashed into his mind; and then he replied:

“No; upon consideration it would be best that I go alone. Where is the wedding to take place, sir?”

“Here,” said Cornwallis. “You came to this plantation blindfolded; you could not find your way here again, alone.”

“I shall leave the place with my eyes open,” said Tom, “and shall note its location as I ride toward the town. And now,” after a short pause, “if we have quite finished, I shall be on my way.”

“We have said all that we can say, for the present,” said Cornwallis.

“Then,” said the young swamp-rider, as he bowed with dignity to the three British officers, “I will bid you good-night, gentlemen, and trust that we shall meet soon again.”

Sultan was at the door. Tom sprang upon his back and shook the rein. Then he waved his hand to the officers on the steps, for they had followed him with considerable ceremony through the hall; in a moment he was dashing along the well-remembered road leading from his father’s plantation. He followed the track toward the city for some time; then drew rein and listened. There was no sound on the road behind, no evidence that he was being followed. Assuring himself of this, he wheeled Sultan into a narrow road leading northwest, and went dashing light-heartedly to meet his comrades at the Indian’s Head.