CHAPTER XV

HOW TOM DEERING FOUGHT HIS FIRST FIGHT UPON THE SEA

WHEN the schooner was well beyond pursuit she dropped in close to shore, and word was sent to the men who guarded the horses to take them back to Marion’s camp. Then the vessel got under way once more; it was no time to loiter, as the frigates might make sail after them at any time.

Tom, sick at heart at his failure to rescue his father, had decided to stick to the Defence until he saw Laura at least in safety somewhere; and several others of his command were delighted at the prospects of a cruise upon deep water. Next morning Tom approached his uncle upon the subject of Laura.

“I’ve been running out of the port of Baltimore,” said Captain Deering, “for a long time, and we have some folks at Baltimore. You don’t remember your Uncle Ben’s family, I suppose? I’ve been to see them once or twice during the last year, and a fine, healthy lot of boys and girls they are, and Ben and his wife are as hearty as can be. Suppose I run up the Chesapeake, and have Laura stop with them for awhile?”

“An excellent idea,” said Tom, much relieved. “And I’m glad you thought of it, for Laura’s safety has been troubling me a great deal.”

The run along the coast up to the Chesapeake was enlivened by a number of chases by British vessels; there was one, a sloop-of-war, of about the same tonnage as the Defence and carrying not many more guns, which Captain Deering ran from with great regret.

“I’d like to train Long Tom on her,” said the old sea-dog, patting the long pivot gun, amidships; “but as I’ve got Laura on board, I suppose I must show the sloop a clean pair of heels.”

When they reached Baltimore, after a narrow escape from a brig and two fleet schooners which were cruising up and down at the mouth of the bay, Tom and the captain saw Laura safely housed with Uncle Ben, who was delighted to receive her; then, after many “good-byes” they once more sought the Defence.

As it happened the harbor of Baltimore was in great commotion just about that time; a great fleet of merchantmen, fifty sail in all, were waiting for a chance to sail, but the British fleet outside kept up such a vigilant watch that it seemed as though the time would never come. A brave and resolute officer, Captain Murray, who had at one time served in the land force and afterward in the infant navy, was engaged by the merchants of the port for the post of commodore of the fleet.

His personal charge was a “letter of marque,” the Revenge, carrying a crew of fifty men and eighteen guns. A few days before, Captain Murray had signaled the fleet to make sail; but upon venturing into open water he had encountered a greatly superior force and was compelled with his entire fleet to run up the Patuxent for safety.

However, he had now received word that the enemy, grown tired of waiting, had sailed, and he was making ready for another attempt. Knowing that the Defence had lately entered the port he paid her a visit next morning in his gig.

“Captain Deering, I believe,” said the commander of the letter of marque.

“Yes, sir,” said the old sailor, who stood in the waist, overlooking some repairs to the topsails, which had been badly torn by a discharge of small shot from one of the British vessels.

“I am Captain Murray, of the Revenge,” said the visitor. “The fleet which you see in the harbor is about to sail to-morrow; I have come to you to know how conditions are outside.”

“There seems to be plenty of the enemy’s craft,” grinned Captain Deering, “and they are mighty liberal with their shot, for witness of which look at my topsails,” and he waved his horny hand toward the rent canvas which some of the sailors were stitching and patching as they sat with their backs to the bulwarks.

“I’ve been asking for delay,” said Captain Murray; “but the merchants want their cargoes afloat, and will listen to nothing else but immediate sailing orders, they having heard that the enemy had sailed.”

“I know what they are,” said the skipper of the Defence. “These land-lubbers are never satisfied. If their old tubs are held back they rave and tear; and if they are taken out in the face of the enemy and are captured or sunk they go on worse than before. Tar my old hull, captain, there’s no way of pleasing such swabs.”

“I see you’ve been in some such position as mine yourself,” said Captain Murray.

“I have,” returned Captain Deering. “I convoyed a fleet out of Charleston before the British took the town. They gave me no peace till I got their old hookers out; and then when the enemy bore down on us, six sail strong and mounting as many guns as I had men, they scuttled here and there like a lot of ducks in a rain-storm. Result was that about half of ’em was seized; and of course when I ran back with the others the entire blame was put upon me.”

“Just so,” said the captain of the letter of marque. “I’m afraid that is how it is going to be with me. When do you sail, Captain Deering?”

“At the next tide,” answered the other.

“Could you be prevailed upon to sail with the fleet?” inquired the other anxiously. The trim look of the Defence, the bright, well-kept guns and the brisk businesslike crew had taken his fancy. The schooner would be no mean addition to his fighting force, and he awaited the answer with interest.

“If the fleet,” said Captain Deering, “sails when I do, and means to stand to its guns if the enemy is sighted, I’ll stick by you while I have a shot in the locker.”

“I thank you,” said Captain Murray gratefully. “There is to be a meeting of the captains, upon the Revenge, this morning. We are going to arrange matters before sailing.”

Now, although the merchant fleet numbered fifty sail and some of them were large vessels, very few of them carried guns. It was plain, therefore, that even this great collection of craft would be comparatively helpless under the fire of a few light, well armed, fast sailing vessels of the enemy. It was to effect some sort of a system of defence that the commodore had called the captains together, and the meeting upon the Revenge ended in terms of agreement being entered into by the armed ships, to support one another in case of attack. Signals were agreed upon for the entire fleet, and then all retired to their respective vessels to await the turning of the tide.

In the gray of the morning the boatman’s whistle sounded through the Defence; all hands turned out to up anchor and make sail.

“This will be our first experience at deep-water fighting,” said Tom to Nat Collins as they, with the remainder of the swamp-riders’ band, stood in the stern, ready to lend a hand when required.

“You expect fighting, then?” said Nat.

“To be sure. You see how sharply we were pursued in running in? Well, if they would exert themselves so much against a single schooner, it stands to reason that they will double their efforts against a huge, helpless fleet like this. The Chesapeake will see some gunnery this morning, and before the sun gets very high, in my opinion.”

“And your opinion’s a good one, my lad,” said the gruff voice of Mr. Johnson, the schooner’s mate, who was passing just then. “There are some of the British lying outside there, ready and waiting for this fleet of old pine planks; and they’ll dance with delight when we show ourselves in open water.”

There was a great flurry and noise in the vast gathering of merchantmen; their capstans clanked, their blocks and rigging creaked, their seamen chanted as they hauled upon the ropes. Then one after another they got under way; the Defence and the Revenge, followed by the other vessels carrying guns, led, under easy sail; the fleet as it passed down the bay and out into the Atlantic made an imposing appearance.

The shore line had not yet been dipped under the sparkling waters, when Mr. Johnson’s prophecy came true. A fleet of privateers suddenly hove in sight, close under the land. The Revenge flew the signal for a superior force, and ordered all unarmed vessels to return to port, and the others to rally about her. The Defence promptly bore up in answer to the signal, but, to the shame of the others, only one brig followed her example; the rest ran for Hampton Roads.

The British fleet consisted of a large ship of eighteen guns, a brig of sixteen and three schooners; and with one accord they stood in for the body of the merchantmen.

“There will be a general capture if that is allowed,” said the skipper of the Defence to his mate.

“Ay, ay,” growled Mr. Johnson. “It’s time for the Revenge to show her teeth, if Murray expects to do anything.”

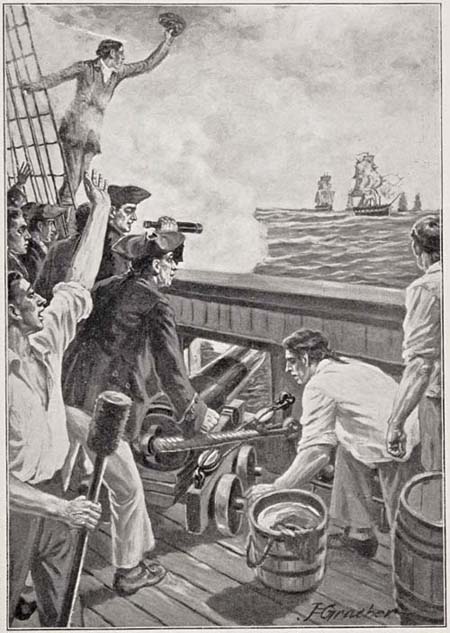

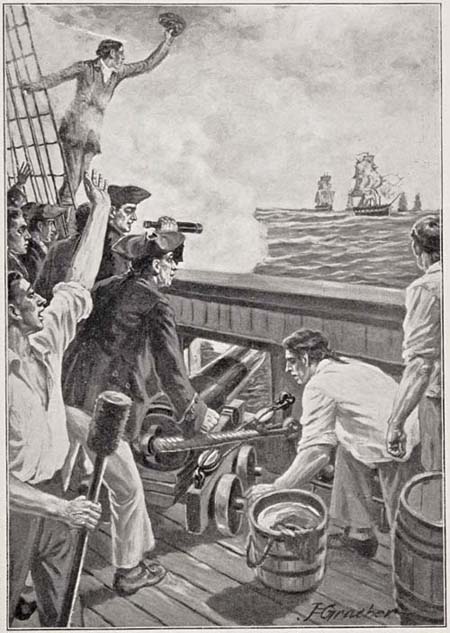

“And for the Defence, too,” said Captain Deering. “Ready the Long Tom, Mr. Johnson; we’ll try a round shot at that nearest schooner; she’s too saucy by far for the weight she carries.”

The long gun was charged and the captain himself sighted it.

“There is a long, slow swell,” said he to Tom, “and that’s the best sort for gunnery afloat. You can time the rise to a fraction of a second. The best gunners are going to win this fight, for everything is in their favor.”

He ran his eye along the polished length of the pivot gun, then applied the match. Long Tom barked sharply, the solid shot went skipping across the waves like a heavy-winged bird; there came a quick crackling sound upon the schooner fired into and her foremast, splintered close to the deck, went, in a tangle of rigging and spars, over the side.

“Well aimed,” praised Mr. Johnson, admiringly. “She’s out of the fight for awhile, anyhow.”

“There goes the Revenge,” cried Tom.

The letter of marque had put herself into a tight place; in order to give his merchantmen time to escape, Captain Murray had awaited the approach of the privateers, and in a short time he was between the fire of the ship and brig. As Tom spoke the Revenge let go both broadsides and she reeled trembling under the shock. As Captain Deering had predicted, good gunnery was going to be felt in that long, slow swell; the firing of the Revenge was almost perfect, and the damage done by her broadsides and smaller guns during the next half hour was very great.

“WELL AIMED” PRAISED

MR. JOHNSON

The two uninjured schooners bore up on the Defence and engaged her; the American brig here entered the fight, with the brass carronades with which she was armed. She took the attention of one of the schooners from the Defence, and Captain Deering headed for the other with his bow guns barking like vicious dogs and the powder-smoke almost covering his vessel’s advance. The steering-gear of the privateer had been damaged by a well-placed shot from the long gun early in the action; so she could not manœuvre as she otherwise would have done; the result was that the Defence laid herself alongside, and with a wild cheer the seamen and swamp-riders, led by Tom and the mate, sprang over the rail and rushed among her crew. These latter, apparently, were not accustomed to this style of fighting, for after a weak resistance they threw down their arms and cried for quarter.

Captain Deering directed that they should be driven down below and the hatches battened down; then placing a half dozen men on board the captured craft to manage her, he drew off. The American brig was still engaged with the third schooner; the latter was the lightest armed and manned, and as the brig seemed fully capable of providing her with entertainment the Defence went about and bore up for the Revenge.

Captain Murray was fighting his vessel with desperate resolution; but, by this time, his ammunition began to grow low, for they had been hotly engaged for a full hour, and his fire had somewhat slackened. And now the gallant officer’s heart leaped with delight as he saw the Defence heading for the brig, upon his starboard; for with the attention of this vessel attracted from him for a space he felt that he could deal with the ship.

Tom Deering, who had sailed upon many coasting trips in the Defence before the outbreak of the war, was at the helm; Captain Deering was superintending the loading of his guns with canister and musket balls; Mr. Johnson was mustering a boarding crew in the waist. As they neared the brig, which greeted them with a scattering fire of small arms and a broadside which did little or no damage, the captain shouted to Tom,

“Down your helm—hard!”

The signal had been arranged between them; the brig manœuvred to meet the expected movement of the schooner; but Tom promptly threw his helm up, and a swinging spar became entangled in the rigging of the Defence, whose mate at once, with a body of seamen, sprang to make the tangle secure. The schooner was now in a position from which she could rake the brig from stem to stern.

“Fire,” cried Uncle Dick. The guns, loaded with the canister and musket balls, swept the British ship’s decks, and in a few moments there was not a man to be seen. Those who had not fallen by the fire had sought safety below decks; Mr. Johnson was about to give the word to board, when the lashings gave way, and the two vessels drifted apart.

The guns of the Defence were given time to cool and commander and crew looked about them. The ship which had engaged the Revenge had hauled off; the third schooner, after inflicting sufficient damage to the rigging of the American brig to prevent pursuit, had also drawn away. Then Captain Murray, whose vessel had suffered severely, having borne the pounding of both British ship and brig for an hour, flew the signal to cease firing. He knew that it would not be possible for them to take the British vessels, so a continuation of the action would only be a waste of ammunition.

Within a half hour the enemy had drawn together to make repairs; then they hoisted what sail they could, and all five stood out to sea, while the Revenge and Defence re-entered the harbor with the crippled brig limping, as it were, in their wake. For this gallant action the skippers and crews received the thanks of the merchants of Baltimore. The Defence was somewhat damaged by the British fire; so Captain Deering delayed long enough to refit; and there being no enemy now to fear the merchant fleet sailed in safety to their different destinations. One morning the Defence also slipped out of the bay and was soon bounding swiftly over the sparkling waters of the Atlantic, on her way south.