CHAPTER XVII

HOW A TRAITOR TO HIS COUNTRY WAS TAKEN AND LOST

THE hardships of the following weeks were never forgotten by Tom Deering nor Cole; the entire state of Virginia seemed overrun with the enemy in small parties; they were compelled to lie concealed for days at a time in the hut of a slave, in the cabin of a woodman or in the dwellings of patriots of higher rank. Sometimes these shelters were not to be had; and in such cases they slept in the woods or the thickets. Food was scarce, and many days they scarcely broke their fast.

At length joyous news reached them. Lafayette had set out from Baltimore in the latter part of April and had arrived on the 29th, after forced marches of two hundred miles, at Richmond. This was the first news of the gallant marquis that they had heard since leaving the camp of General Greene on the Don, weeks before. They were not more than a hundred miles or so from Richmond at the time, and at once set out for that place.

“Great things have happened, Cole, since we started on this journey,” said Tom, “and greater still are going to happen.”

News had reached them that on March 15th Greene, with an army of above 4,000 men had been attacked by Cornwallis at Guilford Court House, and they learned that while the Americans had fallen back, Cornwallis was so badly crippled that he could not follow up his advantage.

“And they say,” said Tom, “that Lord Cornwallis intends to march north and endeavor to conquer Virginia. Well, let him come; I suppose Lafayette will be ready for him, and perhaps he will find that Virginia is as tough a bone to pick as Carolina.”

They were riding, while Tom spoke, along a narrow and little frequented road; it was late on the second day of their journey since hearing of the entrance of the French general into Richmond, and they had already began to wonder how far they were from the town. Standing some distance from the road, among a clump of trees was a long, low building that looked like a schoolhouse. The two stopped to examine it carefully before venturing into full view of its possible occupants.

“It looks like a schoolhouse,” said the young swamp-rider, “and, if it is, should be deserted at this time. But there is no telling, in these days, for——”

But he never finished the sentence.

A scream rang out from the building at which they were gazing, and almost at the same instant the door burst open and a boy of possibly fifteen darted forth. After him followed a man in the uniform of a British general of brigade, and two soldiers, one of whom carried a rope.

“Stop, you dog,” cried the officer in a high, harsh tone. “Stop, or I fire!”

He held a heavy pistol in his hand; the fleeing lad saw it and stopped, terror-stricken.

“Come back,” directed the officer, a sneer curling his lip at the promptness of the obedience. “Come back, you young hound, and answer the questions which I ask you.”

The boy retraced his steps reluctantly. A girl of about sixteen, meantime, had emerged from the building with two small children clinging to her skirts; fear had blanched all their faces; they gazed, trembling and silent, at the boy and the officer.

“We are needed here, Cole,” said Tom, evenly. “I wonder how many there are in the party at the schoolhouse?”

Cole bent his brows in an expression that expressed his fear that there were more of them than were visible.

“You stay here,” said Tom. “Dismount and have your rifle ready. I’m going over there to speak to those redcoats.”

Cole, without a word, did as commanded; he squatted among some bushes in a spot from which he had a clear view of the schoolhouse; his rifle was held between his knees, ready for anything that might occur.

The lad at the schoolhouse, white-faced and with quivering lip, stood before the British officer; he was a slight, delicate boy, at best, and seemed unaccustomed to rough treatment. The redcoat glared at him like an animal, blood hungry and enraged.

“I want the truth,” said he.

“I have told you the truth,” was the boy’s reply. “I know nothing.”

“You lie!” Turning to the soldier who held the rope, the officer proceeded, “Corporal, bring the halter here; perhaps that will bring him to his senses and induce him to tell the truth.”

The girl, who stood in the doorway with the children, screamed sharply and, running forward, she threw her arms about the boy’s neck.

“No, no,” she cried. “Please don’t harm him; he is my brother; he knows nothing.”

“Corporal,” ordered the officer, “take her away.”

Despite her cries, the girl was dragged away; the boy forgot his own danger and sprang toward the two soldiers, his eyes flashing.

“Let her go,” he cried, his pale cheeks flushing with indignation. “Take your hands off, you cowards!”

“Ah, you have spirit, have you,” cried the officer, his laugh sounding harsh and unpleasant upon the evening air. “Well, you’ll need it before many minutes, my lad, if you don’t loosen that tongue of yours.”

“I tell you again, I know nothing about the American general’s army; I did not see them; I do not know how many or how few men there are in Richmond.”

“Corporal, the halter,” cried the officer; “there is no use in our wasting words here.”

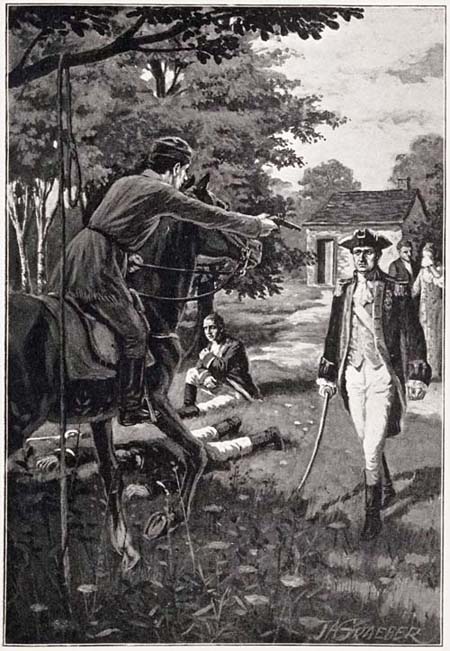

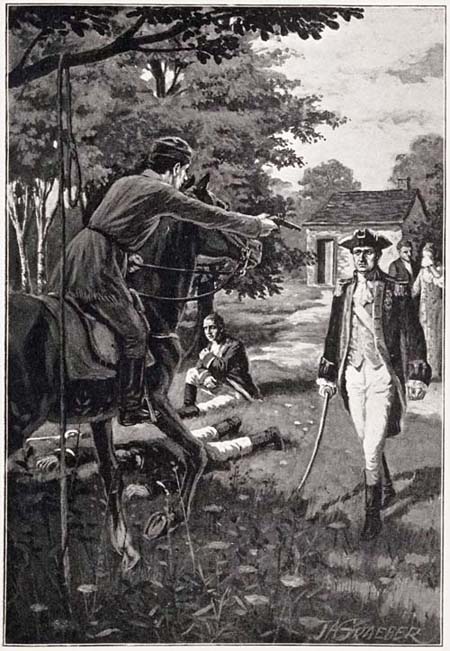

The British corporal brought the rope; the boy’s eyes widened as he looked upon it, but his lips closed firmly. Without a word more it was tossed over the limb of a near-by tree and the corporal was widening the noose when Tom rode up.

“Just one moment,” said Marion’s young scout. “I would like to know what this little pleasantry means, if you please.”

He sat upon Sultan’s back and gazed coolly into the faces of the three redcoats. The officer had put down his pistol some few minutes before, and now clapped his hand to his sword. He was a handsome man, with piercing eyes that contained, also, something that was cold and cruel; his nose and chin were prominent and aggressive, demonstrating a bold and enterprising spirit—a spirit capable of great things or the most base. He looked at the young swamp-rider for a moment, and then said, sneeringly,

“So you would like to know what this little pleasantry, as you call it, means, would you?”

“Yes,” replied Tom Deering, his voice as even as though he were talking to Cole by the camp-fire, and his eyes as steady as though he were gazing at an empty horizon line, “I have some curiosity on that point. If you see your way clear to enlightening me I should be obliged to you.”

“And, suppose,” said the British brigadier, “suppose I should refuse?”

“In that event,” spoke the scout, “I would venture a guess—and a pretty accurate one, I fancy.”

“Indeed?” The bitterness of the officer’s sneer increased. “You flatter yourself upon your coolness, I take it; but this time, at least, you have made a mistake.” His sword suddenly flashed out from its scabbard, and in a voice thick with rage, he shouted:

“You rebel dog, I’ll teach you a lesson for your insolence. Down from your horse!”

THE OFFICER SPRANG

FORWARD

Tom sat still, gazing into the passion inflamed countenance before him; seeing that he did not move to obey, the officer sprang forward, his sword ready for a blow. When it descended Tom received it upon the steel barrel of his holster pistol, not even troubling himself to draw his sword.

“Now,” said he, gazing with irritating calmness into the other’s eyes, “you really should not allow yourself to give way to these sudden fits. You are of a rather stout habit, and apoplexy is not a thing to be tempted.”

For a moment the brigadier seemed unable to speak, so enraged was he. Then he managed to shout an order to the corporal; and the latter rushed toward his rifle which stood leaning against the schoolhouse wall. But his hands had no sooner closed upon it, than a shot rang out from the bushes at the roadside and he fell prone upon his face. At this the other soldier sprang at the young man, plucking a bayonet from his belt; but the heavy ball of Tom’s pistol broke his shoulder and he sank beside his comrade.

“Now, sir,” said Tom sternly, “you are my prisoner.”

The British brigadier looked at him gloweringly for a moment; his sword was held as though he meditated another spring, but Tom checked any idea which he might have had of such an attempt.

“If you desire to throw away your life,” said the young scout, “attempt to escape. If I raise my hand you will be shot from the cover along the road just as your corporal was.”

There was a haggard, despairing look in the British officer’s face as he, at length, laid down his sword. Tom called Cole from his post, and the giant negro mounted guard over him. In a few moments Tom discovered that the three redcoats had ridden up to the schoolhouse just as the children were about leaving it for the day. The boy whom they were about to hang, young as he was, was the schoolmaster; the girl and the two younger children were his sister and brothers, who had clung to him in his danger, even after all the others had scattered, terror-stricken, to their homes about the countryside.

“Richmond,” said the young schoolmaster, “is about three miles away, straight ahead. Keep to the road; you can’t help but strike it.”

Cole bound the prisoner upon his horse, which was found tied behind the schoolhouse; the young girl and her brother thanked them with tears in their eyes; and then they mounted and rode away in the direction indicated.

It was quite dark when they, at length, sighted the lights of the town from a rise in the ground; they skirted a clump of woods and entered a lane which was lined with trees upon each side and was very dark. However, as it seemed to lead directly to Richmond, they pushed ahead without any hesitation. They had ridden well into the lane, when a volley of shots rang out; Cole clutched at his arm, and the prisoner’s horse fell kicking in its death agonies.

Cole took his rein in his teeth and, following Tom’s example, drew his pistol as he set spurs to his horse. With great leaps Sultan and Dando bounded forward and as they sped down the dark lane they heard their late prisoner’s voice crying after them, triumphantly,

“When you reach De Lafayette, tell him how you caught me, and how I slipped through your fingers!”

Within an hour after escaping this ambush Tom was in the camp of Marquis de Lafayette, and was explaining his mission to that brave gentleman himself.

“It is almost a miracle that you have escaped capture,” said he, speaking with a slight French accent. “Your ride from North Carolina must have been filled with many perils.”

“Yes, general,” answered the youth; “but the strangest of all happened on the road just below the town.”

“Ah! and what was that?”

In a very few words Tom told him of his capture of the British brigadier, the ambush, and the prisoner’s cry when he found himself safe with his friends once more.

The general’s keen eyes flashed. “What was he like—your prisoner?” he demanded. “Describe him!” and Tom began to tell what he could remember. But almost at the first word General de Lafayette came to his feet with a spring, and his clinched fist struck the table a blow that made it dance.

“It was he,” came from his lips in almost a shout. “It was the arch-traitor Benedict Arnold himself! He is here with Phillips, and is leaving a trail of rapine behind him.” The marquis clapped Tom on the back, as he continued, regretfully: “My boy, you have escaped fame by a hair’s breadth; by to-night’s work on the road you came within the wink of an eye of writing your name with your sword-point upon the pages of your country’s history!”