CHAPTER III

HOW THE BRITISH SHIPS RAN FROM CHARLESTON HARBOR

ON the 9th of November, which was but a few days previous to Tom Deering’s adventure with the British, the Provincial Congress of South Carolina resolved “by every military operation to oppose the passage of any British armament”; and this order was issued to the commandant at Fort Johnson, Colonel Moultrie. The fort itself was strengthened, more men were enlisted, and bills of credit were issued. The blow for which all had been waiting seemed now about to be struck; the redcoats and patriots were about to grapple in that fierce struggle which was to last eight long years and set a continent free.

Colonel Moultrie had taken up his headquarters at Haddrill’s Point, which was being fortified; it was here that the training of his men was going forward, and the place had the appearance of quite a formidable camp.

The eastern sky was beginning to gray under the hand of approaching morning, when the sentinel on guard at the upper road caught the sound of flying hoofs rapidly approaching him. His musket quickly came around and he stood ready to receive friend or foe.

“Halt!” he cried.

The galloping horse was pulled up so quickly as to almost throw him back upon his haunches.

“Who goes there?” demanded the sentry.

“A friend,” came the voice of Tom Deering.

“Advance, friend, with the countersign.”

Tom walked his snorting horse forward.

“I have not received the countersign,” said he. “But I have urgent business with Colonel Moultrie, and must see him at once.”

“Against orders,” said the sentry. “I’ll call out the sergeant of the guard, though, and leave him to settle it with you.”

In a few moments the sergeant had presented himself. Tom was led forward into the light of a camp-fire, where the sergeant carefully questioned him.

“I can answer no questions,” said the boy, “unless asked by Colonel Moultrie or——”

“Captain Marion, perhaps,” said a voice behind him.

Tom turned quickly; within a foot of him was the small, dark officer with the aquiline nose and the burning black eyes, whom he had carried across the river in his skiff on the night when Fort Johnson was taken.

Francis Marion was, at this time, past his fortieth year. He had been a planter, his only previous military experience having been in the war with the Cherokees some years before; in this he had gained some fame as a leader of a “forlorn hope” at the battle of Etchoee, in which the Carolinians had defeated the French and Indians. Then he had been a lieutenant in the regiment of Middleton. Colonel Moultrie, who was in command of the patriot forces, had been captain of the company in which Marion served at that time.

“So,” said Marion, “you would like to see Colonel Moultrie, would you, my lad?”

Tom, holding the bridle of his horse with one hand, raised the other in salute.

“Yes, captain,” answered he promptly.

“Well,” said Marion, “I owe you something for your service that night on the river.” He laughed lightly. “You see, I have not forgotten it; nor have I forgotten the fact that you, single handed and alone, captured a fortified position.”

Captain Marion was pleased to regard Tom’s errand lightly, it seemed; a boy must always prove that his doings are worth the consideration of his elders. In spite of the fact that he recognized in Tom Deering no ordinary lad, Marion could not accept his word that his business with Colonel Moultrie was not some hair brained freak. Tom saw all this in the dark, smiling face of the soldier before him; and he recognized the fact that he must come down to plain dealing and take him into the matter before he could hope to see the colonel.

“Captain Marion,” said Tom, with a glance at the sergeant and his file of listening men, “can I have a word in private with you?”

Still smiling, Marion led the boy a little way apart, but well out of earshot.

“Now,” said he, “tell me all about it.”

“Would you consider it a serious matter,” asked Tom, looking him candidly in the eye, “if the British ships came up and bombarded the city in the night?”

Marion’s face grew grave, and he glanced keenly at the boy’s intent face, an alert look stealing into his eyes.

“I would consider it very serious,” said he, in reply, his voice sober and low.

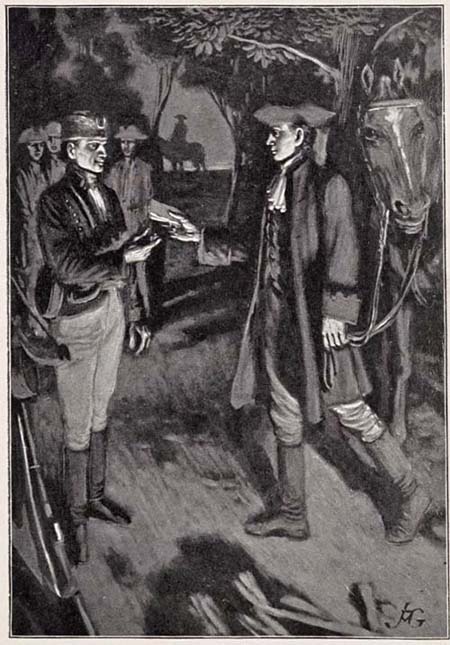

“There is to be such an attack to-night,” said Tom. He drew the captured despatches from his boot leg, and held them out. “This packet I took from an officer of Tarleton’s dragoons two hours ago, some distance below here.”

“Have you examined them?”

“I have, in order to make sure that I was not at fault. I did not wish to come here with nothing to substantiate my statement.”

Marion took the packet and glanced hurriedly through the papers. After a moment’s examination he said, quietly:

“Come with me.”

Within a quarter of an hour a dozen officers were gathered in Colonel Moultrie’s cabin in the center of the encampment. The captured papers were before them; Tom Deering stood at the table answering the questions with which they plied him.

“This attempt seems mere madness,” said Colonel Moultrie, at length. “How do they hope to get their vessels past the fortified points without danger of being destroyed?”

MARION TOOK THE PACKET

This seemed to be the general opinion of the council; but Marion, who happened to glance at Tom at that moment, saw an eager light in his eyes.

“Speak out, lad,” said he, kindly. “If you have anything to say upon this question I have no doubt but that Colonel Moultrie will be glad to hear it.”

“Of course,” said the colonel. “You have done us too great a service already, my boy, for us to refuse to listen to you.”

“I just wanted to say, sir,” exclaimed Tom, eagerly, “that the British ships can get up to the city, and without the slightest danger to themselves.”

The colonel looked startled.

“You are sure of what you say?” he demanded.

“I am positive. They can come up by way of Hog-Island channel.”

“But that is not deep enough for their heavy vessels,” cried an officer.

“At high water,” said Tom Deering, calmly, “there is water enough to float the largest ship in their fleet, providing they have a man at the wheel who knows the course. I have come through the channel many a time with my uncle, Captain Deering, of the schooner Defence.”

This information set the council in a state of great excitement; Tom was thanked over and over for what he had done.

“You have, without doubt,” said Colonel Moultrie, “saved us from making a fatal mistake.”

Before the sun was three hours high a plan of action had been formulated and was in progress of execution. Captain Deering was summoned in hot haste from his schooner, which lay in the river, and ordered to cover and protect a party detailed to sink a number of stone-laden hulks in the narrow Hog-Island channel. The Defence, some weeks before, had been fitted up with carronades and a long thirty pounder cannon, and she was just the ready, quick-sailing craft for the work.

By early afternoon the hulks were being floated into the channel, the Defence hovering about them like a great bird watching over its young. The work had scarcely begun, however, when the British lookouts discovered it, and the Tamar bore down upon the hulks, firing from her bow guns as she came. The Cherokee was only a little behind her sister craft in promptness of action, and opened with her lighter guns, also. The Defence answered with her carronades, but their range was not great enough, and she did but little damage; the guns from Fort Johnson opened; a few shots were effective; but the firing was discontinued as soon as the British war-ships showed signs of hesitation. Meanwhile the alarm was beat at Charleston, where the troops stood to their arms. But the time was not yet; the Tamar and Cherokee, seeing that they could not frighten the blockading party off, went about and retreated beyond range.

From this time on the local patriots began to proceed vigorously. Ships were impressed and armed like the Defence, and they were badly needed, for the British in the harbor became more and more troublesome. Captain Thornborough, the officer in command of them, began to seize all vessels within his reach, entering or coming out of the port.

Of the newly-gathered fleet of the Americans Captain Deering was placed in charge. Heavy artillery was mounted on Haddrill’s Point and the work of fortification at the same place was hurriedly completed. A new fort was raised on Jones’ Island and another one begun on Sullivan’s Island, some distance below the city; the volunteers were constantly coming in, swelling the ranks of the patriots both ashore and afloat. Among these latter was Tom Deering’s father; the planter armed a small sloop and manned it with a crew of slaves, who gladly offered to follow him against the British.

But Tom, to his father’s surprise, refused to join him.

“Is it possible, Tom,” demanded he, sternly, on the morning upon which he formally took charge of the sloop as an officer of the colony, “that you have suddenly grown faint-hearted?”

“Faint-hearted! I!” Tom looked at his father reproachfully. “You don’t think that, father, surely! Have I not done some service, already, for the cause of liberty?—not much, of course, but still, enough to prove that I am ready to go to any length against oppression.”

“You have done some things,” said Mr. Deering, his eyes alight with pride, “that have made me thank the good God who had given me such a son. But,” and his face grew grave once more, “it seems strange that you will not enter the service of the colony, now that she needs you.”

“I have thought the matter over very carefully,” answered Tom, “and have concluded that I shall be better as I am.”

“Tom!” his father’s face grew white. “What do you mean?”

“If I enlist,” returned Tom, “I shall be forced to march in the ranks and obey orders. If I remain free, I can do as I will; and by so doing I can render much more effective service. Those despatches which I captured are not the only ones that will be carried through the outlying districts under the cover of night; there is information to be gained of the enemy’s movements and plans, by one who knows the roads, the cane-brakes and swamps, and has the courage to dare the British dragoons. This is the work that I have laid out for myself, father, in this fight. And this is the work, I think, that I can best do.”

“Tom!” The planter clasped his hand and threw one arm about him; “forgive me for what I have said. I might have known, my lad—I might have known.”

The whole of the long winter and spring passed; the British had all retreated to their ships; while the colonists were deeply absorbed in preparations for the defence of the city. Inland, parties of loyalists, or Tories, had risen and were slaying and burning, but their ravages were confined to a small district as yet. Jasper Harwood, Tom’s half-uncle, and his son Mark, were at the head of a band of these partisans, and they were carrying terror wherever they went. Moultrie sent small parties in pursuit, now and then; but these only served to check the outrages for a space; when the patriots once more returned to the city the slaying and burnings were at once renewed.

Tom did splendid service against these desperate bands. In company with Cole, his giant servant, he penetrated very frequently into their districts, and often gained information that saved both lives and property. During this time, Marion, now a major, was in command of the depot of supplies at Dorchester and it was with his small force that Tom was most frequently in touch. In this way he came to realize the genius and resolution of this small, kindly man with the burning, deep-set, black eyes; for at no time was he unready to spring into the saddle and dash at the head of his men to the rescue of some imperiled section; at no time was his invention at fault for a plan of onset or ambush.

But the constant rumors of the coming of a strong fleet to reinforce the Cherokee and Tamar caused Marion to ask for a change of post to Charleston, where he would be more actively engaged. This was granted him; he was once more appointed to the Second Regiment under Colonel Moultrie and stationed at Fort Sullivan, on the island of that name which stands at the entrance to Charleston harbor and within point-blank shot of the channel. Tom, during the long months at Dorchester had become devoted to Marion and this, together with the expectation of a battle, caused him to follow him to Fort Sullivan—or Fort Moultrie as it was then called, in honor of its commandant.

Tom helped to build the fort; for when he arrived there it was scarcely more than an outline. It was constructed of palmetto logs, a simple square, with a bastion at each angle, sufficient to cover a thousand men. The logs were laid one upon another in parallel rows, at a distance of sixteen feet, bound together with heavier timbers which were dovetailed and bolted into the logs. The work of constructing this fort was a good preparatory lesson for the great conflict that was to follow. Tom grew brown and tough and sinewy with the long days of labor in the sun; the wonderful strength of Cole, the dumb-slave, was a constant source of astonishment to both officers and men; to the amazement of all he would lift, unaided, a great piece of massy timber to crown an embrasure and set it in place, or, when horses were scarce, go down on the beach and drag the ponderous tree trunks from the water. At sight of the open-eyed astonishment of those about him he would throw back his head, his white teeth shining in two even rows, and laugh with the perfect glee of a child.

In spite of the incessant labor of the soldiers the fort was still unfinished when the recently arrived and powerful British fleet appeared before its walls. Colonel Moultrie’s force consisted of four hundred and thirty-five men, rank and file, comprising four hundred and thirteen of the Second Regiment, and twenty-two of the Fourth Artillery. The fort at this time mounted thirty-one guns; nine were French twenty-sixes; six, English eighteens; the remainder were twelve and nine pounders.

The day before the British hove in sight, Tom Deering was witness to an exciting scene which took place between General Charles Lee, whom the Continental Congress at Philadelphia had recently sent to take command of the Army of the South, and Colonel Moultrie. The two officers were standing upon a bastion, looking seaward; Tom and Cole were bolting some timbers together, near at hand.

“It is madness to attempt a defence of this point,” said General Lee. “The fleet is even now in the roadstead and the works, here, are far from being finished.”

“I disagree with you, general,” returned Colonel Moultrie.

“But, Colonel Moultrie,” cried General Lee, not seeming to relish having his opinion so candidly opposed, “how are you going to defend yourself?”

“With the guns of the fort,” said the colonel; “and the brave men who will be behind them.”

“All very well, my dear sir, if it were Frenchmen or Spaniards who manned the attacking fleet; but they are British ships, sir! British ships, and sailed by British tars!”

General Charles Lee had been trained in the English army, and he had, perhaps, naturally enough, an overweening respect for the prowess of an English fleet. It is fortunate that this feeling of awe was not shared by Colonel Moultrie and his men.

“Let them once get within range of my heavy guns,” said the colonel, “and it will make no difference as to what nation they belong. We shall make them run from Charleston harbor, just the same.”

“Your fort presents, at present, little more than a front to the sea,” protested General Lee. “Once let them get into the position for enfilading and you cannot maintain your position.”

“I will risk it,” said Colonel Moultrie. His officers were with him in this; and Lee’s authority was not great enough to force them to evacuate their position against their will.

On the 20th day of June, 1776, the British ships of war, nine in number, and consisting of two vessels of fifty guns, five of twenty-eight, one of twenty-six, and a small bomb-vessel, sailed up the harbor under the able command of Sir Peter Parker. They drew abreast of the fort, let go their anchors with springs upon their cables, and began a terrible bombardment. They strove, after a time, to gain a position for the destructive enfilading fire which General Lee so feared; but the Defence, the Tartar sloop, commanded by Tom’s father, and several other small vessels, came down boldly and maintained such a stubborn resistance, that Sir Peter quickly displayed signals ordering the attempt to be abandoned.

Fort Moultrie at the beginning of the fight had but five thousand pounds of powder; this small supply had to be used with great care.

“Not a shot must be wasted,” cried Colonel Moultrie; “every one must do execution. Let each officer in command of a gun aim it in person.”

This command was obeyed, and its results were frightfully fatal to the British and their ships. In the battle the Bristol, Sir Peter’s flag-ship, lost forty killed and wounded; Sir Peter himself lost one of his arms; the Experiment, another fifty gun vessel, lost about twice as many. The fire of the fort was directed mainly at the heavy craft. Tom Deering, as he toiled with rammer and sponge at one of the French twenty-six pounders, of which Marion had charge, heard that little officer constantly call to his brother gunners:

“Look to the Commodore—look to the heavy ships; they can do us most damage!”

In the heat of the action the Acteon, one of the smaller of the enemy’s ships, being hard pressed by the Defence and Tartar, ran aground and immediately took fire. At this point the British Commodore would have been forced to strike his colors, or be destroyed, but suddenly the powder ran out and the fire of the fort slackened and finally ceased altogether.

Struck with astonishment at this the British also ceased their fire, thinking the fort had been abandoned.

“We must secure ammunition,” cried Colonel Moultrie, his face ashen. Here was victory all but in his grasp, and to have to give it up would be almost fatal in its effect upon his men.

“The schooner Defence has a large supply,” said Marion, to his commander, as he wiped the black powder stains from his face.

“But she is nowhere in sight,” said Moultrie, sweeping the harbor with his glass.

Tom stepped forward, his hand at the salute.

“Well,” demanded the colonel.

“I saw the Defence chased into Stone Gap Creek awhile ago,” stated the lad eagerly. “She is safe, though, for see,” and he pointed shoreward, “there are her topmasts above the trees.”

“Good,” exclaimed Marion, his face lighting up.

“But how can we reach her? The enemy’s vessels will not allow her to come out,” said the colonel.

“We can go to her,” ventured Tom, hesitatingly, for it seemed presumptuous for him to offer a suggestion to his commander. “The Tartar is lying under the guns of the fort. We could reach the Defence in her. The British could not follow us up the creek; they draw too much water.”

The ammunition that remained on board the Tartar, save a few rounds, Tom’s father gladly gave up to Colonel Moultrie, and a few guns resumed service from the fort, but firing slowly. Under mainsail and jib the gallant little sloop then stood out, in the teeth of the British, heading for the creek where the Defence was lying. Major Marion, Tom Deering and Cole stood upon her deck, watching a brig-of-war which had just started to head them off.

“She’s a fast sailer,” said Mr. Deering, a shade passing over his face, after he had watched the quality of their pursuer for a few moments.

“Do you think she can overhaul us?” asked Major Marion.

“There is no question about it,” returned the planter, “if she is given time enough. But the distance to the creek is short; we may reach there. Then, with the help of the Defence, we can fight her off on the return run.”

The Tartar had arrived within hailing distance of the mouth of the creek, when the brig suddenly discharged a lucky shot from a long bow gun that splintered the sloop’s mast and left her lying a helpless hulk upon the waters.

“It’s all over,” said Marion, quietly.

“The boat remains,” said Mr. Deering. “Quick. You have still time to gain the Defence.”

“And you, father?” said Tom.

“I remain with the sloop,” answered the planter.

“But you will be taken prisoner!”

“I will not leave my crew,” said his father, firmly. “There is not room for us all in the single yawl.”

“Then I will remain, also,” said Tom.

“You will join Major Marion in the boat,” commanded the planter, evenly. “Carolina has need of all her youth. It would be a needless sacrifice for you to throw yourself into the hands of her enemies.”

Despite the boy’s protests, his father remained firm; so with a heavy heart Tom climbed into the boat with Marion. Cole would have remained behind with his master; but the planter, who recognized the great attachment of the giant black to his son, and saw how valuable he would be during these dangerous times, promptly ordered him, also, into the yawl.

They were just pulling into Stone Gap when a small boat with an armed crew left the British brig and pulled for the wrecked Tartar. So it happened that Roger Deering was one of the first prisoners of war taken in Carolina.

Apparently the British skipper did not realize the significance of the sloop’s errand; for after taking her crew from her she set fire to the hull and sailed back to rejoin the other vessels in the line of battle.

An hour later the Defence crept out of Stone Gap Creek and headed for Fort Moultrie. She was a swift sailer, and the old salt who commanded her knew how to make her do her best. So, in spite of pursuit and flying shot, she anchored under the guns of the fort and quickly transferred her powder. The British, during the protracted lull in the fort’s fire, had drawn closer; but now, under the brisk and accurate cannonade they withdrew again to their first position. The fight then continued, hotter than ever; shortly afterward the fort received another supply of powder from the city, which did much to encourage the defenders.

The cheers, however, that greeted the arrival of the ammunition had scarcely died away when a distant roar of voices raised in exultation came from the British fleet.

“Look; the flag,” cried some one.

A solid shot from one of the flag-ship’s heavy guns had carried away the flag and it fell, fluttering like a wounded bird, outside the walls of the fort. In an instant Tom Deering, who was once more helping to serve the gun, threw his rammer to Cole and leaped upon the wall. A storm of canister swept about him and a hundred voices shouted for him to return; but, without hesitation he leaped to the sandy beach below, between the ramparts and the enemy, seized the fallen colors, stuffed them into his bosom and then with the help of the mighty, outstretched arm of Cole, scrambled back inside.

Again the flag was run up to the top of the staff, by means of fresh halyards; the sight of it seemed to give the colonists renewed courage, for they turned to the conflict with a resolution that was unconquerable. The British ships were fast becoming mere wrecks, so seeing that a continuation of the combat would be mere folly, the signal flags were flown at the masthead of Commodore Parker’s vessel to cease firing. Ten minutes afterward a fleet of ships, with sails hanging from the rigging in shot-rent rags, and with hulls battered, leaking and torn with canister, ran out of Charleston harbor in disorder.

“They carry your father with them, a prisoner,” said Major Marion, to Tom Deering, as they leaned, watching, upon a hot gun.

“But they shall not keep him,” cried the lad, “to die in their prison hulks! He shall be free! I am only a boy; but the whole British navy shall not keep me from him. It may be a month, a year, or even more, but he shall be free in spite of all the fleets and armies they can send!”