Chapter 26. Bristol.

Present day. Clifton Antiquarian Club. Bristol, England.

Charlie Winston was buzzing with energy. He

was going to be very famous soon, as his discoveries would

reverberate around the country and the world. Today, he was in

Bristol, England, where he would be giving his first lecture on the

subject of his discoveries to an audience of scholars. When this

speech was over, he would publish his findings in a new book.

Doubleday had already given him a very healthy advance for the

manuscript. Many of his friends were here, and this would be an

entertaining weekend of scholarly discussions about American

History. Winston was seated at the head table next to the podium,

waiting for the Club’s Chairman to introduce him.

"Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. I am

John Waithe, the current Chairman of the Clifton Antiquarian Club,

and it is with great pleasure that I welcome each of the scholars

in this room to what I believe will be history in the making." The

sixty year-old Englishman was tall and thin, with a healthy head of

white hair. His round, gold-rimmed glasses rested down on the edge

of his sharp nose, giving the impression that the speaker could not

decide whether he wanted his glasses on or off. He wore a tweed

jacket, a slightly wrinkled blue-and-white pinstriped shirt, and a

navy blue bow-tie. But what distinguished him today was his big

smile. He did not seem to mind that his teeth were orthodontically

imperfect and slightly yellow or that he was in the early stages of

gum disease. He did not mind that the wrinkles around his eyes

furrowed more when he smiled. Today was not a day to hold back. For

a lover of ancient and antique things, especially antique things

involving Bristol, today was a wonderful day.

Charlie Winston sat in the front row with his

program, excited about the day's events. Each of the fifty-three

scholars in the room had been invited to attend a "pre-viewing" of

important new documents recently discovered by Charlie Winston in

Seville behind the wall of the Virgin of the Navigators painting.

The purpose of the meeting was to have the documents verified and

interpreted by scholars before a public announcement was made to

the rest of the world.

"As you may know, our Antiquarian Club was

founded here in Bristol in 1884. Since that time, our society has

been dedicated to the search for truth in history, especially when

that history has anything to do with England, or more particularly,

Bristol. And today, we have a real treat--proof that our great

little city of Bristol was the true birthplace of the Americas. We

have been waiting for this day since 1908, when our former

Antiquarian Club Chairman Alfred Hudd first posited the theory that

Bristol was intimately connected to the discovery and naming of

America. Over one hundred years after Alfred Hudd’s first

postulation, Emory University Professor Charlie Winston, in the

great tradition of Indiana Jones, found a treasure trove of

documents hidden behind a painting in the Alcazar in Seville,

Spain. Those documents will prove, once and for all, that our

history books have it wrong. But the full telling of the story

belongs to the discoverer, so I would like to proudly introduce to

you our good friend, noted scholar, and the man who is going to put

Bristol back on the map, Emory University Professor Charlie

Winston!”

The room erupted with applause. Charlie

Winston took the podium, armed with his Mac Book Pro and some index

note cards.

“Welcome distinguished scholars, and thank

you for inviting me here today. This is a story about a brave

explorer, a wealthy benefactor, a violent murderer, and a sneaky

schemer, all of whom played a part in the discovery and naming of

America. Could we please turn down the lights?” The lights were

dimmed and Winston began a slide show from his laptop. Winston

tapped the microphone to make sure it was working, and then began

the lecture.

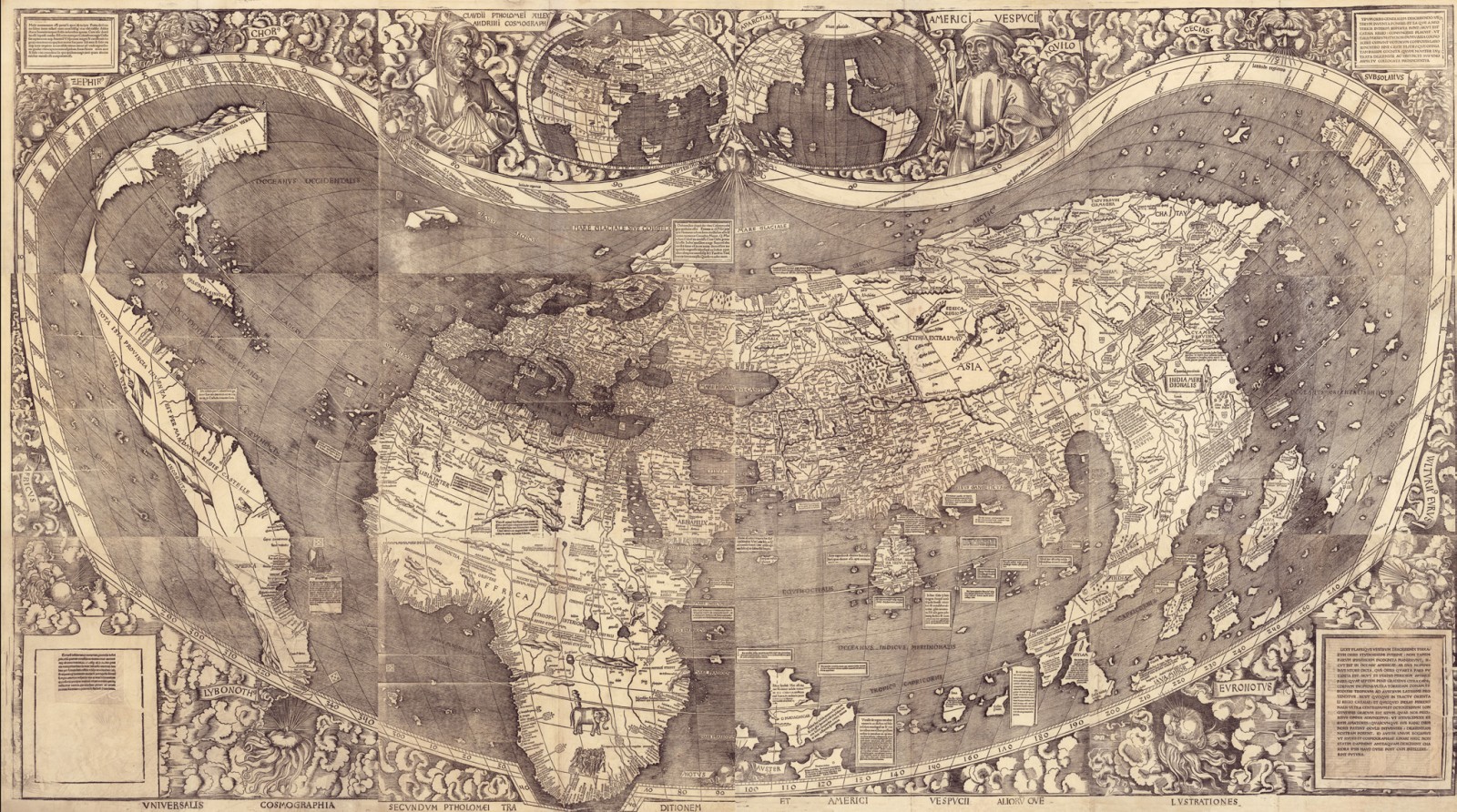

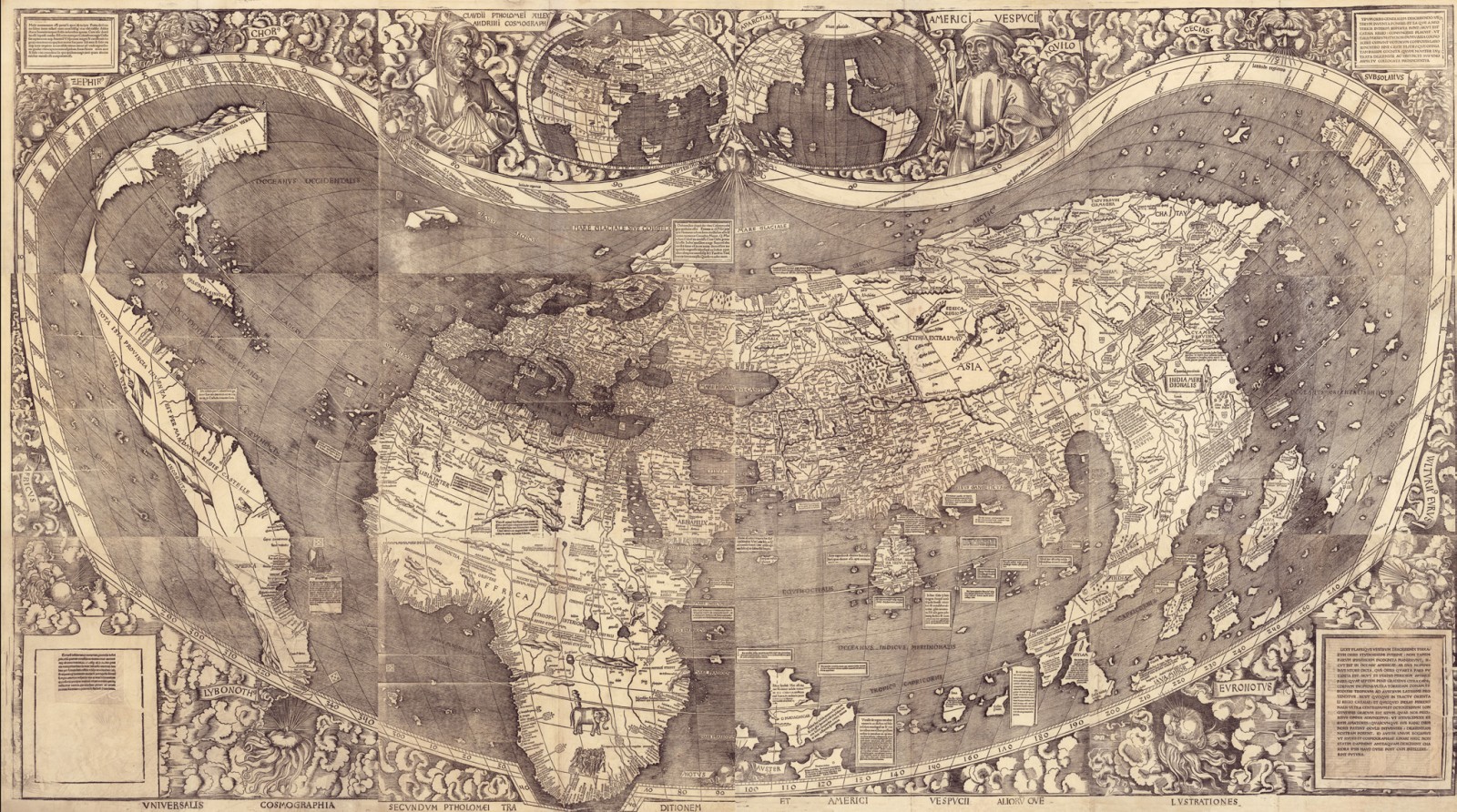

“Our history books tell us that America was

named after Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci. Why?” Winston paused

for a few moments. “Why? There is only one document in the annals

of time upon which this entire thesis is based. That is the

so-called ‘Waldseemüller Map,’ drawn in 1507 by a German monk named

Martin Waldseemüller. The map today sits in the Library of

Congress, and it has puzzled historians for centuries. Here is a

copy of it.” Winston clicked his air mouse and a large black and

white map appeared on the screen:

"This 1507 map, for the first time, lists the

name 'America' on the South American mainland:

When the monk Waldseemüller published the

1507 map, he included an engraving upon which he wrote this glowing

accolade of Vespucci.” Morse clicked the air mouse again:

“'Now that the regions are truly and amply

explored, and another fourth part has been discovered by Amerigo

Vespucci (as will be heard later), I do not see why anyone can

prohibit its name being given the name of its discoverer Amerigo,

wise man of genius, Amerigen, that is, land of Amerigo, in other

words America, since Europe and Asia also took their names from

women. Its location and customs of its people can be known easily

in the account of Amerigo's four voyages that follow.'

“Keep in mind that a monk in France living in

a monastery would have no idea who discovered what. The only

explorer hanging around the monastery giving an account of events

at that time was Vespucci, and no one was there to contradict him.

Columbus was dead. John Cabot was dead. Why should the monk not

believe Vespucci was telling the truth?

“So what is strange about this map? Well, the

first thing that historians have noted is that it would be quite

bizarre to name a new land ‘America’ after someone whose first name

was ‘Amerigo.’ The general rule of naming lands was that lands were

named after the first name of royalty--for example, Charleston,

Georgetown, Jamestown--but after the last name of a commoner.

Vespucci was not royalty; like Columbus, he was a commoner. Why

would anyone name a land discovered by a commoner after his first

name instead of his last name? Let's remember, did we call the

district where our nation's capital sits the District of

Christopheria? No, we called it the District of Columbia, after the

last name of Columbus. So that naming has always seemed odd. If

Vespucci really wanted the mapmaker to name the new land after him,

why didn’t he suggest that he call it 'Vespuccia'?

“The second strange thing about the

Waldseemüller map is that it pretty accurately shows the Pacific

Ocean, which would not even be discovered by Balboa until 1513,

some six years later! How could a German monk who had never

traveled to the New World so accurately depict the western

coastline of the Americas and the Pacific Ocean when no one had

ever traveled there before? There is only one logical answer.

Balboa did not discover the Pacific Ocean. Someone else did, and it

was not Amerigo Vespucci.

“So how do we explain these two oddities on

the Waldseemüller map? The answer that I have postulated for many

years is that the famous explorer John Cabot was the one who

actually discovered the Pacific Ocean, in 1499, some fourteen years

before Balboa. I have suggested that Cabot wrote the name ‘America’

on his own maps, for reasons we shall discover shortly, and then

Vespucci, in an act of thievery on the high seas, stole Cabot’s

maps. Then when Waldseemüller saw the maps given to him by

Vespucci, which were stolen from Cabot, the monk must have asked

Vespucci about the name ‘America’ on the map. Vespucci, thinking

quickly, and desiring to weasel his way into history, lied to the

German monk and told him that the lands were named ‘America’ after

him.

“Farfetched? Some historians said so when I

first espoused this theory some ten years ago. But in the meantime,

recent discoveries of centuries-old documents have finally proved

this theory correct.

“Now, with your indulgence, I would like to

set forth my own view of what truly happened. In the 1470s, Bristol

was a fishing town, and the fishermen caught cod in the waters near

Iceland. In 1475, seventeen years before Columbus’ famous voyage,

the King of Norway issued a declaration prohibiting British

fishermen from fishing for cod in Icelandic waters. This forced the

men in Bristol to seek additional fishing lanes further to the

west. In 1479, four Bristol merchants received a royal charter to

find another source of cod. Two ships, the Trinity and the George,

were launched in 1480 in search of cod in the Western Atlantic.

There is evidence that these fishermen, sometime between 1480 and

1491, landed on a small island off Newfoundland which they called

'Hy-Brassyle,' or sometimes just 'Brassyle,' named after the brazil

wood which they found there. Today, we actually have a 1481 letter

from a Bristol marine merchant with the initials 'R.A.' advising

that he will be sending salt to his fishermen 'at Brassyle' to salt

the codfish." Winston clicked the air mouse and a picture of the

1481 letter appeared on the screen. "This certainly suggests that

the Bristol fishermen had found Hy-Brassyle in America by 1481.

There is additional evidence of this discovery. In 1490, the

earlier ruling of the Danish King was reversed and the Bristol

fishermen were once again allowed to search for cod near Iceland.

But instead of returning to Icelandic waters, the Bristol fishermen

declined the offer, telling the King of Norway that they no longer

needed to fish for cod near Iceland. That probably means that the

fishermen found a more abundant supply of cod in the Western

Atlantic.

"Now that brings us to the hero of our story,

Venetian explorer Mr. Zuan Chabotto, or as he is known by his

Anglicized name, John Cabot." The professor adjusted his blue

bow-tie and took off his blue blazer, putting it over a chair. He

clicked the air mouse for another photo, and John Cabot's picture

came up.

"John Cabot was a great person. Now there is

a man we should name a holiday after. John Cabot was born in Genoa,

Italy. Cabot's family moved to Venice when he was a small boy.

Venice at that time was the epicenter for sailors. If you wanted to

learn how to be the pilot of a ship, this is where you learned.

John Cabot was a poor young man from a poor family, but he excelled

at navigation and ship piloting. Cabot's hero was Marco Polo, and

he longed to find a passage to the west from Europe which could

lead all the way to the island of Japan, where he believed there

would be gold and spices galore. In 1480, at the age of thirty, he

moved with his wife and three children to Bristol, England. Now

Cabot couldn't sail a ship in Bristol right away because he didn't

have any money. So he worked for a rich Bristol cod merchant named

Richard Amerike. Remember that man who wrote the letter in 1481

about salting the cod, who had the initials R.A.? Well, that's him.

That was Cabot's boss, the man who was signing the paychecks.

“How do we know that Richard Amerike was

Cabot’s boss? In 1908, Alfred Hudd, then the Chairman of this

Clifton Antiquarian Club where we sit today, found pension records

kept in Westminster Abbey which affirmatively show that Amerike

paid Cabot’s pension. So that is an established fact.

“Cabot worked for this cod merchant in

Bristol down at the docks, loading the smelly cod fish off the

boats, grinding it out, day after day for eleven years. Now you can

be sure that in those eleven years, as he is working down at the

docks elbow to elbow with the Bristol fishermen, he hears their

stories about this place called Hy-Brassyle, this new land across

the Atlantic Ocean. He is dying to emulate his hero Marco Polo and

take a ship over there to check it out. Finally, in the eleventh

year, in 1491, he finally saves enough money to build his own ship,

called the Matthew after his Venetian wife Mattea. After one

unsuccessful trip in 1491, he began his voyage to the New World in

1494.

“We know, of course, that Christopher

Columbus set sail in 1492, as our grade school textbooks told us,

but--and here is the important part-- he did not land on the

American mainland. He landed on Santo Domingo (the modern day

Dominican Republic), on Cuba, and on some of the Caribbean islands.

Assuming de Huelva did not get there first, Columbus can take

credit at most for being the first European to land on those

islands in the Caribbean Sea--but that's it! He cannot claim credit

to being the first European since the Vikings to land on the

American mainland, because he wasn't. The laws of discovery at that

time were that when a navigator discovered an island, that entire

island belonged to that navigator’s country. So Santa Domingo,

Cuba, and other Caribbean islands, being discovered by Columbus,

became the provinces of Spain. But by 1492, Columbus had never

reached the mainland of America, so that 'island' did not belong to

Spain and was still fair game. In fact, Columbus would never hit

the American mainland until his third voyage in 1498. In the

meantime, John Cabot beat Columbus to the American mainland by

landing in Newfoundland in 1494. So it was John Cabot, not

Columbus, who can lay claim to discovering America.

“After Cabot returned to England after his

1494 voyage, he decided upon a more ambitious voyage to chart the

eastern coastline of this new land to the west. So he applied to

the English King Henry VII for a Royal Charter. King Henry VII

granted the Charter in 1496, but there was one catch--the King

would not finance the journey. Cabot would have to pay for the trip

himself. In order to get funding for the brave new venture, which

would involve sailing much further than ever before, Cabot had few

choices. He did not know any wealthy bankers. The most reasonable

explanation is that Cabot turned to his wealthy cod merchant friend

and former employer, Richard Amerike. Amerike was happy to finance

the journey because it could have led to information about

additional fishing lanes. I postulate that Cabot, an honorable man,

must have agreed to name any new lands which were discovered after

his friend Mr. AMERIKE." Winston clicked the mouse and a slide with

the name "AMERIKE" in capital letters appeared. Winston clicked the

mouse again. "Is the name ‘Amerike’ sounding familiar? This is a

drawing of Richard Amerike's merchant seal." A circle appeared on

the screen. Inside the circle, were letters going around

concentrically. The letters around the merchant seal spelled

“A-M-E-R-I-C” and then returned to the same “A.' “'AMERICA,'” said

Winston triumphantly. “There it is." The professor paused a few

seconds for effect. “America. America was named NOT after Amerigo

Vespucci, but after the wealthy cod merchant Richard Amerike.”

Charlie Winston looked out on the crowd,

expecting to see surprised and impressed looks. Instead, he saw a

lot of frowns. Most of the scholars were not buying it. Well, truth

is stranger than fiction, he thought. He would just have to

convince them.