CHAPTER III.

THE day after Paul’s departure for London with his lawyer and his uncle, Mr. Gus left the Markham Arms. By a fatality Fairfax thought, he too was going away at the same time. He had gone up to Markham in the morning early for no particular reason. He said to himself that he wanted to see the house of which he had so strangely become an inmate for a little while and then had been swept out of, most probably for ever. To think that he knew all those rooms as familiarly as if they belonged to him, and could wander about them in his imagination, and remember whereabouts the pictures hung on the walls, and how the patterns went in the carpet, and yet never had seen them a month ago, and never might see them again! It is a strange experience in a life when this happens, but not a very rare one. Sometimes the passer-by is made for a single evening, for an hour or two, the sharer of an existence which drops entirely into the darkness afterwards, and is never visible to him again. Fairfax asked himself somewhat sadly if this was how it was to be. He thought that he would never in his life forget one detail of those rooms, the very way the curtains hung, the covers on the tables: and yet they could never be anything to him except a picture in his memory, hanging suspended between the known and the unknown. The great door was open as he had known it (“It is always open,” he said to himself), and all the windows of the sitting-rooms, receiving the full air and sunshine into them. But up stairs the house was not yet open. Over some of the windows the curtains were drawn. Where they still sleeping, the two women who were in his thoughts? He cared much less in comparison for the rest of the family. Paul, indeed, being in trouble, had been much in his mind as he came up the avenue; but Paul had not been here when Fairfax had lived in the house, and did not enter into his recollections; and Paul he knew was away now. But the two ladies—Alice, whom he had been allowed to spend so many lingering hours with, whom he had told so much about himself—and Lady Markham, whom he had never ceased to wonder at; they had taken him into the very closest circle of their friendship; they had said “Go,” and he had gone; or “Come,” and he had always been ready to obey. And now was he to see no more of them for ever? Fairfax could not but feel very melancholy when this thought came into his mind. He came slowly up the avenue, looking at the old house. The old house he called it to himself, as people speak of the home they have loved for years. He would never forget it though already perhaps they had forgotten him. His foot upon the gravel caught the ear of Mr. Brown, who came to the door and looked out curiously. When things of a mysterious character are happening in a house the servants are always vigilant. Brown came down stairs early; he suffered no sound to pass unnoticed. And now he came out into the early sunshine, and looked about like a man determined to let nothing escape him. And the sight of Fairfax was a welcome sight, for was not he “mixed up” with the whole matter, and probably able to throw light upon some part of it, could he be got to speak.

“I hope I see you well, sir,” said Mr. Brown. “This is a sad house, sir—not like what it was a little time ago. We have suffered a great affliction, sir, in the loss of Sir William.”

“I am going away, Brown,” said Fairfax. “I came up to ask for the ladies. Tell me what you can about them. How is Lady Markham? She must have felt it terribly, I fear.”

“Yes, sir, and all that’s happened since,” said Brown. “A death, sir, is a thing we must all look forward to. That will happen from time to time, and nobody can say a word; but there’s a deal happened since, Mr. Fairfax—and that do try my lady the worst of all.”

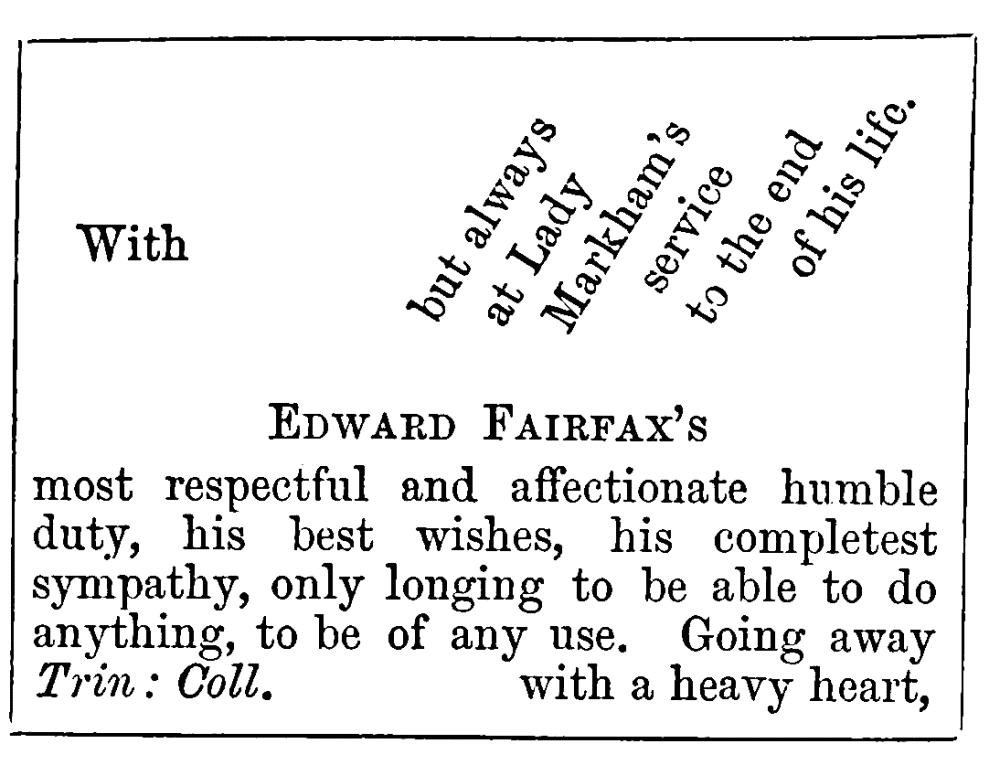

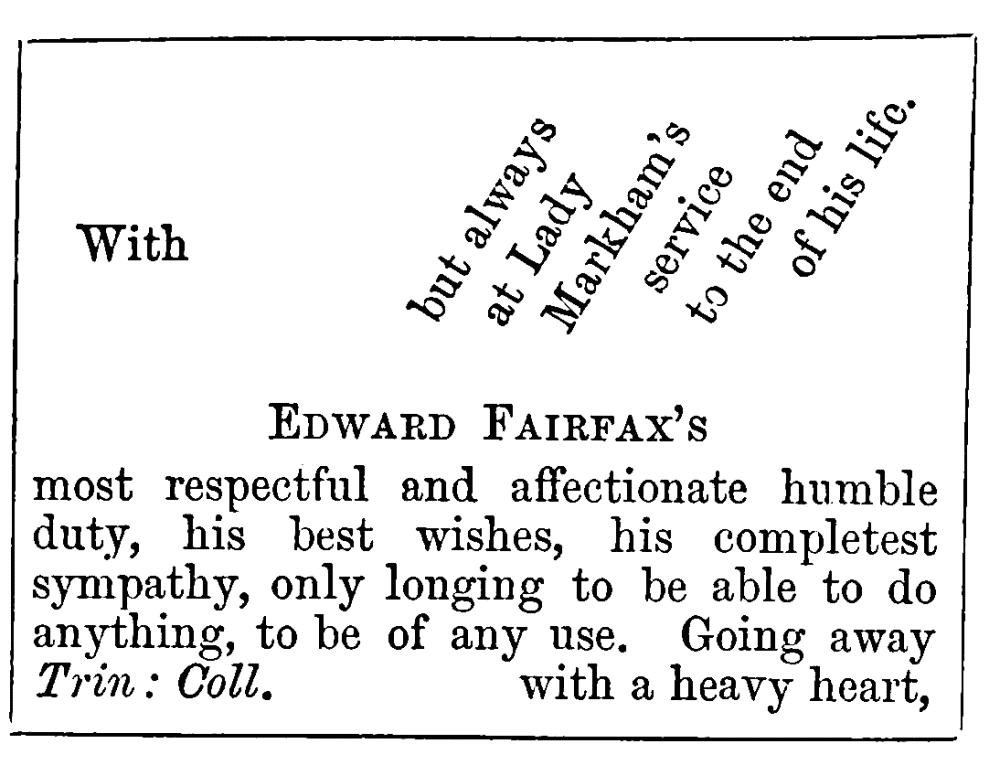

Fairfax did not ask what had happened, which Mr. Brown very shrewdly took as conclusive that he knew all about it. He said half to himself, “I will leave a card, though that means nothing;” and then he mused long over the card, trying to put more than a message ever contained into the little space at his disposal. This was at last what he produced—

When he had written this—and only when he had written it—it occurred to him how much better it would have been to have written a note, and then he hesitated whether to tear his card in pieces; but on reflection, decided to let it go. He thought the crowded lines would discourage Brown from the attempt to decipher it.

“You will give them that, and tell them—but there is no need for telling them anything,” Fairfax said with a sigh.

“You are going away, sir?”

“Yes, Brown”—he said, confidentially, “directly,” feeling as if he could cry; and Brown felt for the poor young fellow. He thought over the matter for a moment, and reflected that if things were to go badly for the family, it would be a good thing for Miss Alice to have a good husband ready at hand. Various things had given Brown a high opinion of Fairfax. There were signs about him—which perhaps only a person of Mr. Brown’s profession could fully appreciate—of something like wealth. Brown could scarcely have explained to any one the grounds on which he built this hypothesis, but all the same he entertained it with profound conviction. He eyed the card with great interest, meaning to peruse it by and by; and then he said—

“I beg your pardon, sir, but I think Miss Alice is just round the corner, with the young ladies and the young gentlemen. You won’t mention, sir, as I said it—but I think you’ll find them all there.”

Fairfax was down the steps in a moment; but then paused:

“I wonder if it will be an intrusion,” he said; then he made an abject and altogether inappropriate appeal, “Brown! do you think I may venture, Brown?”

“I would, sir, if I was you,” said that personage with a secret chuckle, but the seriousness of his countenance never relaxed. He grinned as the young man darted away in the direction he had pointed out. Brown was not without sympathy for tender sentiments. And then he fell back upon those indications already referred to. A good husband was always a good thing, he said to himself.

And Fairfax skimmed as if on wings round the end of the wing to a bit of lawn which they were all fond of—where he had played with the boys and talked with Alice often before. When he got within sight of it, however, he skimmed the ground no longer. He began to get alarmed at his own temerity. The blackness of the group on the grass which he had seen only in their light summer dresses gave him a sensation of pain. He went forward very timidly, very doubtfully. Alice was standing with her back towards him, and it was only when he was quite near that she turned round. She gave a little startled cry—“Mr. Fairfax!” and smiled; then her eyes filled with tears. She held out one hand to him and covered her face with the other. The little girls seeing this began to cry too. For the moment it was their most prevailing habit. Fairfax took the outstretched hand into both his, and what could he do to show his sympathy but kiss it?—a sight which filled Bell and Marie with wonder, seeing it, as they saw the world in general, through that blurred medium of tears.

“I could not help coming,” he said, “forgive me! just to look at the windows. I know them all by heart. I had no hope of so much happiness as to see—any one; but I could not—it was impossible to go away—without——”

Here they all thought he gave a little sob too, which said more than words, and went to their hearts.

“But, Mr. Fairfax,” said Bell, “you were here before—”

“Yes; I could not go away. I always thought it possible that there might be some errand—something you would tell me to do. At all events I must have stayed for——”

The funeral he would have added. He could not but feel that though Alice had given him her hand, there was a little hesitation about her.

“But, Mr. Fairfax,” Bell began again, “you were staying at the inn with—the little gentleman. Don’t you know he is our enemy now?”

“I don’t think he is your enemy,” Fairfax said—which was not at all what he meant to say.

“Hush, Bell, that was not what it was; only mamma thought—and I—that poor Paul was your friend and that you would not have put yourself—on the other side.”

“I put myself on the other side!” cried the young man. “Oh, how little you know! I was going to offer to go out to that place myself to make sure, for it does not matter where I go. I am not of consequence to any one like Paul; but——”

“But—what?”

Alice half put out her hand to him again.

“You will not think this is putting myself on the other side. It all looks so dreadfully genuine,” said Fairfax, sinking his voice.

Only Alice heard what he said. She was unreasonable, as girls are.

“In that case we will not say anything more on the subject, Mr. Fairfax; you cannot expect us to agree with you,” she said. “Good-bye. I will tell mamma you have called.”

She turned away from him as she spoke, then cast a glance at him from under her eyelids, angry yet relenting. They stood for a moment like the lovers in Molière, eying each other timidly, sadly—but there was no one to bring them together, to say the necessary word in the ear of each. Poor Fairfax uttered a sigh so big that it seemed to move the branches round. He said—

“Good-bye then, Miss Markham; won’t you shake hands with me before I go?”

“Good-bye,” said Alice faintly. She wanted to say something more, but what could she say? Another moment and he was gone altogether, hurrying down the avenue.

“Oh, how nasty you were to poor Mr. Fairfax,” cried Bell. “And he was always so kind. Don’t you remember, Marie, how he ran all the way in the rain to fetch the doctor? even George wouldn’t go. He said he couldn’t take a horse out, and was frightened of the thunder among the trees; but Mr. Fairfax only buttoned his coat and flew.”

“The boys said,” cried little Marie, “that they were sure he would win the mile—in a moment——”

“Oh, children,” cried Alice, “what do you know about it? you will break my heart talking such nonsense—when there is so much trouble in the house. I am going in to mamma.”

But things were not much better there, for she found Lady Markham with Fairfax’s card in her hand, which she was reading with a great deal of emotion. “Put it away with the letters,” Lady Markham said. They had kept all the letters which they received after Sir William’s death by themselves in the old despatch-box which had always travelled with him wherever he went, and which now stood—with something of the same feeling which might have made them appropriate the greenest paddock to his favourite horse—in Lady Markham’s room. Some of them were very “beautiful letters.” They had been dreadful to receive morning by morning, but they were a kind of possession—an inheritance now.

“Put it with the letters,” Lady Markham said; “any one could see that his very heart was in it. He knew your dear father’s worth; he was capable of appreciating him; and he knows what a loss we have had. Poor boy—I will never forget his kindness—never as long as I live.”

“But, mamma,” said Alice, loyal still though her heart was melting, “you know you thought it very strange of Mr. Fairfax to take that horrid little man’s part against Paul.”

“I can’t think he did anything of the sort,” Lady Markham said, but she would not enter into the question.

It was not wonderful, however, if Alice was angry. She had sent him away because of the general family anger against him; and lo, nobody seemed to feel that anger except herself.

But it may be easily understood how Fairfax felt it a fatality when he found Gus’s portmanteaux packed, and himself awaiting his return to go by the same train.

“Why should I stay here?” he said. “I did not come to England to stay in a village inn. I will go with you, and go to that lawyer, and get it all settled. Why should they make such a fuss about it? I mean no one any harm. Why can’t they take to me and make me one of the family? except that I should be there instead of my poor father, I don’t know what difference it need make.”

“But that makes a considerable difference,” said Fairfax. “You must perceive that.”

“Of course it makes a difference; between father and son there is always a difference—but less with me than with most people. I do not want to marry, for instance. Most men marry when they come into their estates. There was once a girl in the island,” said Gus, with a sigh; “but things were going badly, and she married a man in the Marines. No, if they will consent to consider me as one of the family—I like the children, and Alice seems a nice sort of girl, and my stepmother a respectable motherly woman——, eh?”

Some hostile sound escaped from Fairfax which made the little gentleman look up with great surprise. He had not a notion why his friend should object to what he said.

But the end was that the two did go to town together, and that it was Fairfax who directed this enemy of his friends’ where to go, and how to manage his business. Gus was perfectly helpless, not knowing anything about London, and would have been as likely to settle himself in Fleet Street as in Piccadilly—perhaps more so. Fairfax could not get rid of his companion till he had put him in communication with the lawyer, and generally looked after all his affairs. For himself nothing could be more ill-omened. He went about asking himself what would the Markhams think of him?—and yet what could he do? Gus’s mingled perplexity and excitement in town were amusing, but they were embarrassing too. He wanted to go and see the Tower and St. Paul’s. He wanted Fairfax to tell him exactly what he ought to give to every cabman. He stood in the middle of the crowd in the streets folding his arms, and resisting the stream which would have carried him one way or the other.

“You call this a free country, and yet one cannot even walk as one likes,” he said. “Why are these fellows jostling me; do they want to rob me?”

Fairfax did not know what to do with the burden thus thrown on his hands.

And it may be imagined what the young man’s sensations were, when having just deposited Gus in the dining-room of one of the junior clubs of which he was a member, he met Paul upon the steps of the building coming in. Paul was a member too. Fairfax was driven to his wits’ end. The little gentleman was tired, and would not budge an inch until he had eaten his luncheon and refreshed himself. What was to be done? Paul was not too friendly even to himself.

“Are you here, too, Markham? I thought there was nobody in London but myself,” Fairfax said.

“There are only a few millions for those who take them into account; but some people don’t——”

“Oh, you know what I mean,” Fairfax said. And then they stood and looked at each other. Paul was pale. His mourning gave him a formal look, not unlike his father. He had the air of some young official on duty, with a great deal of unusual care and responsibility upon him.

“You look as if you were the head of an office,” said Fairfax, attempting a smile.

“It would not be a bad thing,” said the other languidly; “but the tail would be more like it than the head. I must do something of that kind.”

“Do you mean that you are going into public life?”

“That depends upon what you mean by public life,” said Paul. “I am not, for instance, going into Parliament, though there were thoughts of that once; but I have got to work, my good fellow, though that may seem odd to you.”

“To work!” Fairfax echoed with dismay; which dismay was not because of the work, but because the means of getting him out of the place, and out of risk of an encounter with Gus, became less and less every moment. Paul laughed with a forced and theatrical laugh. In short, he was altogether a little theatrical—his looks, his dress, everything about him. In the excess of his determination to bear his downfall like a man, he was playing with exaggerated honesty the part of a fallen gentleman and ruined heir.

“You think that very alarming then? but I assure you it depends altogether on how you look at it. My father worked incessantly, and it was his glory. If I work, not as a chief, but as an underling, it will not be a bit less honourable.”

“Markham, can you suppose for a moment that I think it less honourable?” said Fairfax; “quite otherwise. But does it mean——? Stop, I must tell you something before I ask you any questions. That little beggar who calls himself your brother——”

“I believe he is my brother,” said Paul, formally; and then he added with another laugh: “that is the noble development to which the house of Markham has come.”

“He is there. Yes, in the dining-room, waiting for his luncheon. One moment, Markham!—we were at the inn in the village together, and he has hung himself on to me. What could I do? he knew nothing about London; he is as helpless as a baby. And the ladies,” said Fairfax, his countenance changing, “the ladies—take it as a sign that I am siding with him against you.”

He felt a quiver come over his face like that of a boy who is complaining of ill-usage, and for the moment could scarcely subdue a rueful laugh at his own expense; but Paul laughed no more. He became more than ever like the head of an office, too young for his post, and solemnised by the weight of it. His face shaped itself into still more profound agreement with the solemnity of those black clothes.

“Pardon me, my good fellow,” he said. Paul was not one of the men to whom this mode of address comes natural. There was again a theatrical heroism in his look. “Pardon me; but in such a matter as this I don’t see what your siding could do for either one or the other. It is fact that is in question, nothing else.”

And with a hasty good day he turned and went down the steps where they had been talking. Fairfax was left alone, and never man stood on the steps of a club and looked out upon the world and the passing cabs and passengers with feelings more entirely uncomfortable. He had not been unfaithful in a thought to his friend, but all the circumstances were against him. For a few minutes he stood and reflected what he should do. He could not go and sit down at table comfortably with the unconscious little man who had made the breach; and yet he could not throw him over. Finally he sent a message by one of the servants to tell Gus that he had been called unexpectedly away, and set off down the street at his quickest pace. He walked a long way before he stopped himself. He was anxious to make it impossible that he should meet either Gus again or Paul. Soon the streets began to close in. A dingier and darker part of London received him. He walked on, half interested, half disgusted. How seldom, save perhaps in a hansom driven at full speed, had he ever traversed those streets leading one out of another, these labyrinths of poverty and toil. As he went on, thinking of many things that he had thought of lightly enough in his day, and which were suggested by the comparison between the region in which he now found himself and that which he had left—the inequalities and unlikeness of mankind, the strange difference of fate—his ear was suddenly caught by the sound of a familiar voice. Fairfax paused, half thinking that it was the muddle in his mind, caused by that association of ideas with the practical drama of existence in which he found himself involved, which suggested this voice to him; but looking round he suddenly found himself, as he went across one of the many narrow streets which crossed the central line of road, face to face with the burly form of Spears.