LAUGHING INGIBJÖRG

CHAPTER I.

THORWALD AND INGIBJÖRG ARE CRUELLY TREATED BY THEIR STEPMOTHER, WHO TRIES TO GET RID OF THEM.

Long ago, when giants and ogres still walked about the earth, in a far distant country, there once lived a king and queen. They had two children, called Thorwald and Ingibjörg; but before the children were grown up, the good queen died.

The king, who was very fond of his wife, was quite inconsolable at her death. He lost interest in everything, shut himself up in his own rooms, only coming out to sit and weep beside her grave.

This went on for so long, that at last his ministers came to him, and told him that everything was going wrong in his kingdom, and that there was a rumour abroad, that a neighbouring prince, hearing that the king no longer took any interest in his affairs, meant to cross the water and take possession of the king’s throne and lands. They therefore begged him to rouse himself and look out for another wife, and either go forth and seek her himself, or else send his ambassadors to try and bring back a suitable princess.

At first the king would not listen to a word they said, but after a time he saw that his ministers were right, so he agreed to fit out some ships and send an embassy to several other countries in order to find some fair princess worthy to share his throne.

Soon after the ambassadors had started and were once fairly on the high seas, a great storm arose. The sky grew black as night, the thunder roared and the lightning flashed, and the wind blew so strongly, driving the ships in all directions, that the sailors quite lost their reckoning; their rudders were broken, and they drifted about at the mercy of the winds and waves. At length, after many days, they sighted land; but when they came near, they saw it was quite an unknown shore.

The chief men of the expedition now disembarked, in order to make some inquiries, leaving the sailors in charge of the ships.

For some time they could see no sign of any human habitation, and thought they must have landed on some uninhabited island, but at length they arrived at a small farm, consisting of a few wretched huts.

Not hearing a sound, and seeing no one about, they at first concluded the place was deserted; but when they reached the last hovel, an old woman came forth, who, despite her great age, was both tall and stately, and at once asked them who they were and whence they had come.

“We have been driven here by the storm,” replied the leader, and he then proceeded to tell her the object of their search.

“You certainly have been very unfortunate so far,” answered the old woman, “and I fear there is but little chance of your finding what you seek here.”

While they were talking, the sun had set, and as the weather showed signs of again turning stormy, the ambassadors asked the old woman whether she could give them shelter.

At first she absolutely refused, saying her miserable hut was not fitted to receive people accustomed to live in royal castles; but, as the storm increased, they continued to urge her to let them stay, till at length she consented and bade them enter.

What was their surprise and astonishment to find the inside of this apparently miserable hut richly fitted up like some kingly apartment

Handsome skins covered the floor, soft couches ran round the walls, which were ornamented with richly chased shields and arms, and a bright fire burnt cheerily on the hearth.

As soon as the men were seated, the old woman laid the great oaken table which stood in the centre, and served the strangers with such dainty dishes as might well befit a royal table.

“And do you mean to say that you live here all alone?” asked the chief ambassador, during the meal.

“I might almost say that I do,” replied the woman, “for besides myself there is no one here but my only child Guda.”

“And, pray, may we not see the maiden?” asked the ambassador; for they were all wondering what the girl, living alone with her mother in these strange surroundings, would be like.

Again the old woman demurred; but the more she pretended to hesitate, the more the ambassadors urged her, till at last she consented, and said she would bring her daughter.

When at last she entered by her mother’s side, the ambassadors were almost startled by her marvellous beauty. Tall and fair, like a stately lily, with a perfect wealth of golden hair, falling in shining masses to the ground, Guda appeared before them like the goddess Freya. Surely, they thought, nowhere could they find a lovelier maiden to fill the vacant seat beside the king’s throne.

So, without further hesitation, they at once solicited her hand in marriage, in the king’s name.

The old woman pretended to think they were only joking, and laughed at the idea of the king seeking a wife in a peasant’s cottage, adding that poor girls like her daughter had better remain at home, for such grandeur was not for them, and their ignorance of the ways of the world only brought them to shame instead of honour.

The king’s ambassadors, however, would not be put off, and the more the old woman declared she could not part with her daughter, the more determined they were to take her away with them. At last, seeing the men would take no refusal, she consented to let the girl go, on condition that they would bring her back again, if, on seeing her, the king did not wish to marry her.

To this the ambassadors agreed, and then they all retired for the night.

Next morning the men prepared to return to the ships, and the old woman said her daughter would be ready to accompany them when she had got her things together. Then, to their surprise, they found she had so many packages that it needed all the ships’ crews to carry them to the shore and put them on board.

The mother and daughter now went down to the beach together, talking earnestly, but in such low tones that no one could make out what they were saying; but one man heard the old woman say, “Remember, you must send me back the big stone; I will manage the rest.”

And then they reached the shore, where the old mother kissed her daughter, and, bidding her good-bye, wished her all good luck and prosperity.

Then the anchors were weighed, the sails were hoisted, and the vessels put out to sea, reaching their destination without any mishaps.

When the king heard that his ambassadors had returned, he went down to the shore, accompanied by all the chief officers of his court, to bid the travellers welcome, and when he saw the young girl whom the ambassadors had chosen for his queen, he was greatly delighted, for she was more beautiful than any maiden he had ever seen, and seemed as sweet and good as she was lovely.

He conducted her back to the palace in great state. There a magnificent banquet had been prepared, and soon after the wedding was celebrated, amid the rejoicings of the whole island. The feast lasted three days, and every one who saw the fair Queen Guda in her rich and costly robes, seated on the throne beside her husband, declared no more beautiful queen could possibly have been found, and though the king had loved his first wife, he soon became so completely wrapped up in Guda, that her word was law in everything.

Some months after the wedding, a war broke out in a neighbouring kingdom, belonging to a cousin of the king, who had, therefore, to start off and help him, as his enemies were too strong for him to fight them alone.

The king, therefore, ordered out his war-galleys, and, as he expected to be away some time, he, at the queen’s request, handed her his royal signet ring, begging her to rule the kingdom during his absence, and be a kind and loving mother to his two children, Thorwald and Ingibjörg.

This Guda promised she would do. So the king took a tender farewell of his wife and children, and getting on board his ship, followed by his men, a strong wind rapidly carried the vessels out of sight.

For some little time after the king had left, Queen Guda was very kind to the children. She had them to dine at her own table, gave them fruit and sweets and toys, and often took them for drives in her beautiful chariot, with the cream-coloured horses.

Then one day she asked them to go down to the shore with her and play some games.

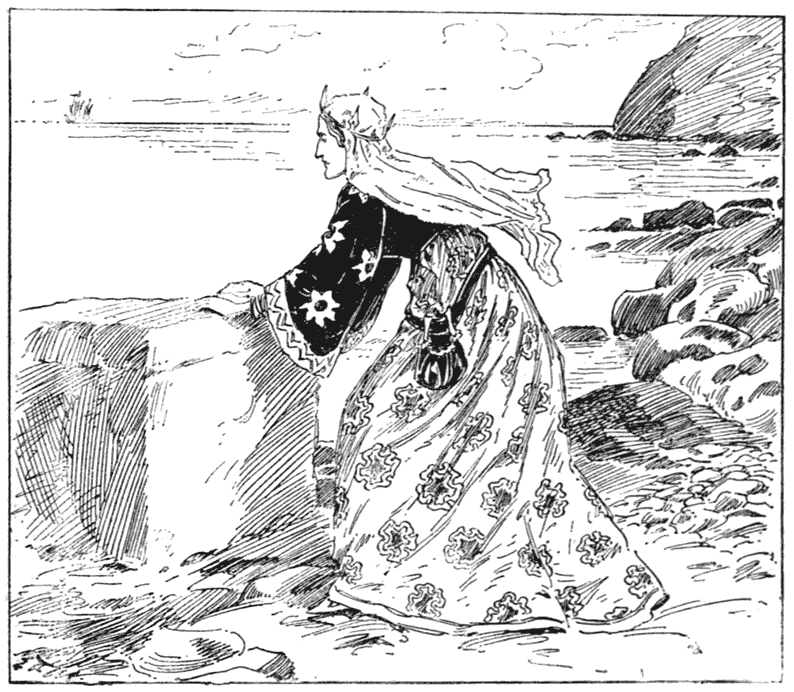

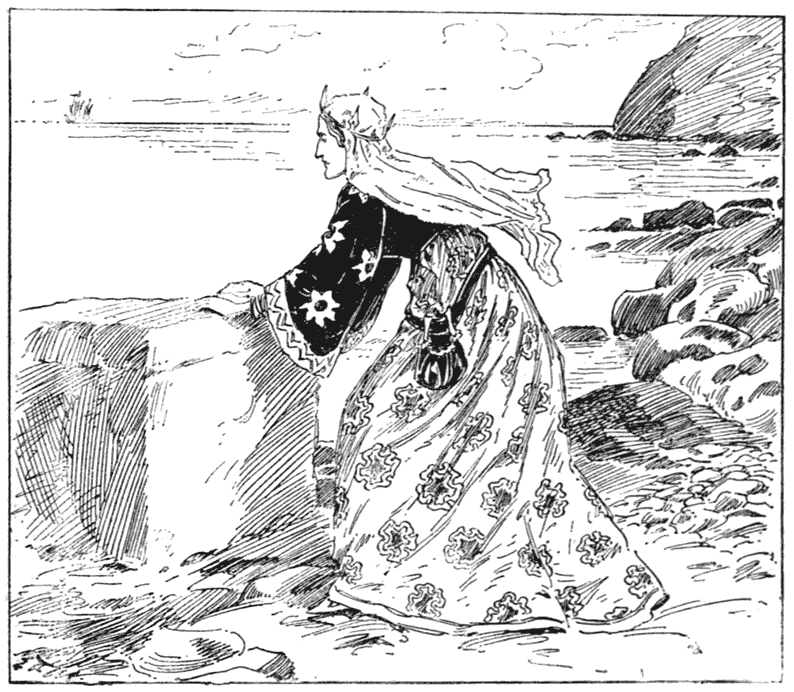

It was a beautiful morning; the sun shone warm and bright, the blue sea was smooth and glistening like a great sheet of glass, and as the tiny wavelets receded, the golden sands were strewn with lovely pink and violet shells and glistening feathery weeds of every hue and shade.

“Oh, Thorwald!” cried Ingibjörg, running up to her brother and laughing merrily, her arms filled with long trails of crimson and green seaweed. “Look how beautiful they are! Let us play at being king and queen, and I will make two lovely crowns.”

“No; come here, children,” said the queen. She had walked some little distance along the shore, and now stood beside a big square stone. Then, as Thorwald and Ingibjörg came near her, she muttered, “Open, oh stone!” And at these words the great square stone parted asunder, showing a large cavity inside, and before the children knew what had happened, Queen Guda had pushed them both in; the stone closed with a snap, and, giving it a strong shove, she rolled the stone into the sea.

“QUEEN GUDA ROLLED THE STONE INTO THE SEA.”

She then returned to the castle weeping, telling her attendants that the children had run away, that she had called them to come back, but all in vain, they would not obey; so she now sent out messengers in all directions, pretending terrible grief at their supposed loss.

CHAPTER II.

HOW THORWALD AND INGIBJÖRG FOUND THEMSELVES AT THE WITCH’S ISLAND, AND WHAT THEY DID.

The two children meanwhile, when they felt the stone closing, tried their utmost to force it open. But all their efforts proved fruitless; the stone remained shut, and the children soon felt, by the rapid motion, that they were fairly out at sea, for, being a magic stone, it floated on the surface of the water instead of sinking to the bottom. The waves tossed it about for many hours, but at length the children felt the motion getting less and less, until at last the stone lay perfectly still.

“I think we must be near land now,” said Thorwald. “There is no motion at all.”

“If you think that, why should not you say the same words the queen did?” replied Ingibjörg.

So Thorwald waited a little longer in order to make sure it was not merely a temporary lull, and then he called out loudly—

“Open, oh stone!”

And immediately the great stone parted asunder, and Thorwald saw they were close to the shore.

The two children then slipped out, and paddled through the shallow water to the land. But though they wandered along the fine dry sand for some distance, they could see no sign of any habitation. They therefore determined to try and build a little hut for themselves.

Now, Thorwald, although but a young lad, had always gone out hunting with his father, who had given him a small gun and hunting-knife. These and his flute, on which he played wonderfully well, the boy never parted with, and he therefore had them with him when he and his sister had gone out with the queen in the morning.

Fashioning a rough wooden spade out of some driftwood for Ingibjörg, he used his knife to such purpose that a large hole was soon dug in the dry sand. This he then covered over with branches cut from the brushwood on the rocks, and leaving his sister to collect dry wood for a fire, he went in search of some birds for their supper. But although successful in shooting a couple, there was, alas! no fire to cook them, and poor Ingibjörg, who was getting very hungry, looked sadly at the food they could not eat.

“You pluck and prepare the birds,” said Thorwald, “and I will go further inland and see if I cannot get some fire.”

So saying, he went up a narrow valley instead of, as heretofore, keeping along the shore, and after he had gone some little distance, he came to a small miserable-looking farm. He could see no one about, so he climbed up the steep slanting roof of the centre hut and peeped down the hole which served as a chimney.

There he saw an old, very ugly, and dirty woman, busily engaged raking out the ashes from the hearth. But he noticed that half the cinders tumbled down among her feet, instead of into the ashpan she held in her left hand. So Thorwald made certain that the old woman must be blind.

He determined, therefore, to enter quietly into the house, and carry off a few live coals. First slipping down the roof, he crept slowly in at the low door, and then, watching his opportunity, he crawled along the wall till he reached the hearth. Then, seeing a small iron cup, he carefully pushed some glowing coals into it, and seeing no one else about, he made sure the old woman was alone, and while she was still busy raking, he crept out of the hut, and, much pleased with his success, hastened back to his sister.

Ingibjörg was delighted when she saw him arrive, and, the fire being all ready laid, a bright flame soon shot up; the birds were roasted, and the two children made a hearty supper, Ingibjörg’s merry laugh sounding again as gay as ever.

Thorwald, somewhat tired with his day’s work, asked his sister to make up a good fire ere they went to sleep, so that it might last all night. But, alas! when they woke next morning the fire was out, so he had to go again to the old woman’s farm to fetch more coals.

This time he begged Ingibjörg earnestly not to let the fire out; but, alack! the little princess, though very willing and anxious to please her brother, had not been accustomed to attend to fires, so, though doing her best by making up a huge fire ere she went to sleep, it was out in the morning.

Ingibjörg even tried to wake up very early in order to put on fresh wood; but, despite all her efforts, each morning the fire was out, and Thorwald had to go every day to fetch fresh fire.

CHAPTER III.

THEIR FURTHER ADVENTURES AND ESCAPE.

Thus the brother and sister lived for some time on the birds and game that Thorwald killed; and Ingibjörg having made a net out of the long tough shore grasses, they also managed to catch some fish and crabs, and their days passed pleasantly enough, while every morning Thorwald went up the valley and brought away some live coals, without the old woman ever finding it out.

Once, after he had taken away the coals, he heard her mutter—

“Ah! those devil’s children! they are a long time in coming, but arrive here at last they must, for I made Guda promise to send them in the stone, and she dare not disobey me. Ah! only let me once get hold of them, and I will very soon put them out of the way.”

Thorwald thought these words must surely refer to himself and his sister, who had arrived there in such a strange manner. He was, therefore, very careful whenever he came to the hut for the fire coals, to make as little noise as possible. He sometimes scarcely dared to breathe for fear the old woman might discover him.

Meanwhile Ingibjörg, who had been very good about staying alone in their little hut, at last became very curious about the old woman, and begged and entreated Thorwald to let her go with him some day. Thorwald, though willing to please his sister, was afraid to trust her, for he knew that the sight of the queer old woman would make her laugh; but he found it very difficult to deny her anything within his power to grant, and when, therefore, she continued to beg him to take her, he at last consented on condition that, no matter what she saw or heard, she must promise him she would not laugh, as, if she did, it might cost them their lives.

Ingibjörg promised she would keep quite still; so the next day the brother and sister started off together for the old farm.

When they got there they climbed up the sloping roof, and, with another warning to keep silent, Thorwald let his sister peep down through the chimney hole. But, alas! what Thorwald had dreaded actually took place.

The old woman, who stood near the hearth, was raking out the ashes so vigorously, that not only did she send them all over the floor instead of into the ashpan, but she made such a cloud of dust that she was soon completely covered from head to foot with a coating of grey ashes, and began to cough violently.

When Ingibjörg saw this, she could not repress her laughter, and a merry peal rang out in the clear air.

No sooner did the old woman hear this, than she chuckled gleefully.

“Ha! ha! ha! So those devil’s children have come at last, have they? Ho! ho! ho! what a joke! Now I shall have them! Ha! ha! ha!”

And with these words she rushed out of the house. She was so quick, that she came up to the children just as they were sliding down the roof, and they might even then have got away, but that Ingibjörg, at sight of the old woman, could not stop laughing; she thought her still more comical-looking when she began to run.

But the laugh now turned to grief, for the old witch pulled some strong leather straps out of her pocket, and, fastening them round the brother and sister, she drove them back into the house. There she shut them up in a lean-to, and secured them firmly with another strap to two strong wooden posts.

The children at first were terribly frightened when they found they could not get away, and Ingibjörg blamed herself greatly for having, through her foolish laughter, brought about this terrible pass.

But the old woman evidently did not mean to starve them, for presently she placed a big bowl of bread and milk before each of them, saying—

“Now eat all you can, and don’t waste anything.”

In the evening she again brought them food in plenty; and this went on for some days.

But, though they were not harshly treated, except that they were never untied, the children grew very weary and tired; the room was almost dark, the only light coming through the hole in the roof, which also served as a chimney. On the third day, the old woman took one of each of their hands, and mumbling and gently biting their fingers, she muttered—

“No, no! Not fat enough yet!”

Thorwald, therefore, determined to make every effort in order to free themselves; but this was no easy matter. At length, after many attempts, he succeeded in biting through the strap that fastened his hands. He was thus able to get at his hunting-knife, which he fortunately always wore beneath his tunic, so the old woman had not seen it, else she would certainly have taken it away. Then, waiting till night closed in and the old witch was asleep, he cut through the rest of the straps that bound him and his sister.

“But the old woman will run after us and catch us if she sees us,” whispered Ingibjörg.

“I have thought of that too,” replied Thorwald; “we must, therefore, make sure she is asleep.” And, creeping cautiously along the floor, he bent over the old hag, who lay snoring in one corner on a great heap of skins.

“She is sound,” he then whispered, turning to Ingibjörg, having first carefully placed another thick skin over the old woman. “We must get away ere she wakens. Come, sister; don’t delay!” And, taking Ingibjörg by the hand, he hurried her out of the house.

“Now you wait behind that great stone,” said he, “while I cut and widen this ditch which runs across the road.” Then Thorwald set energetically to work with his hunting-knife, and ere long had cut a deep wide ditch, throwing up the loose earth to form a bank, which rose up between them and the hut.

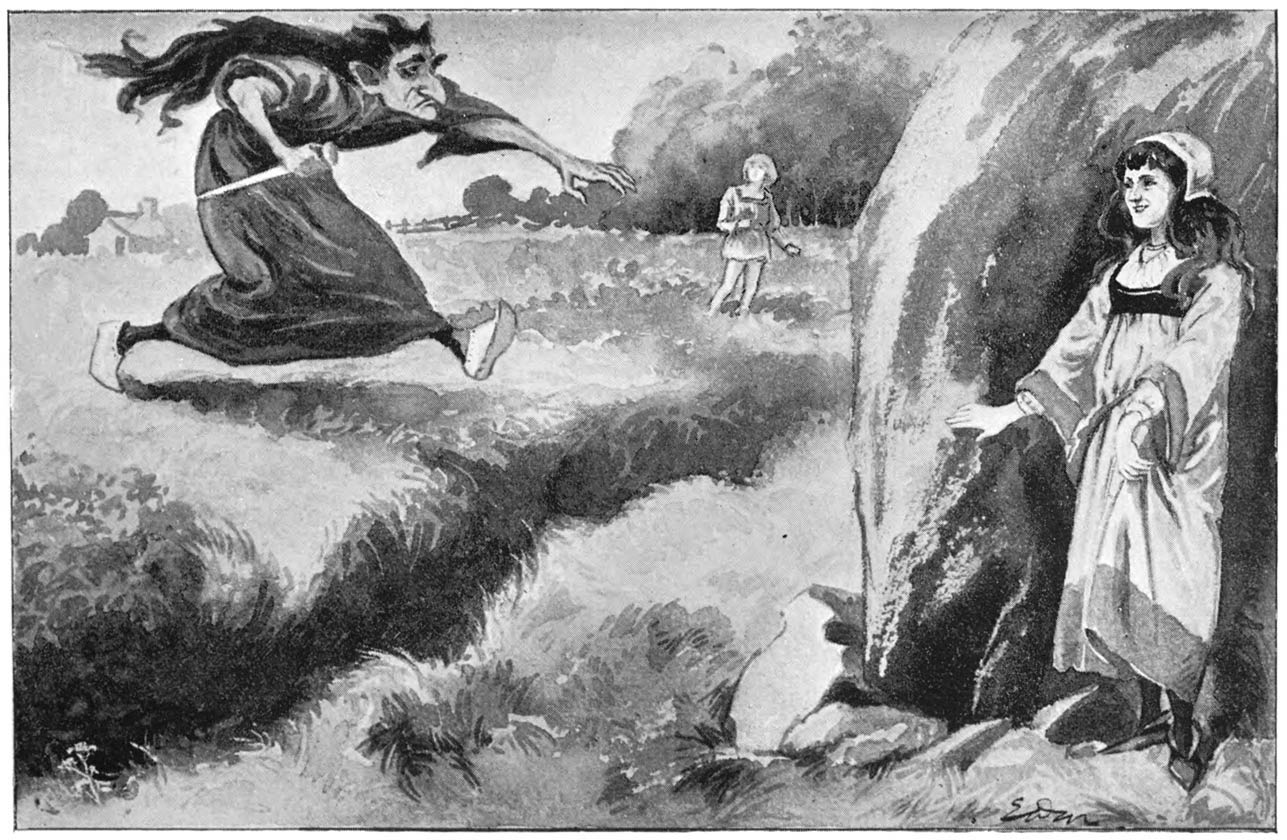

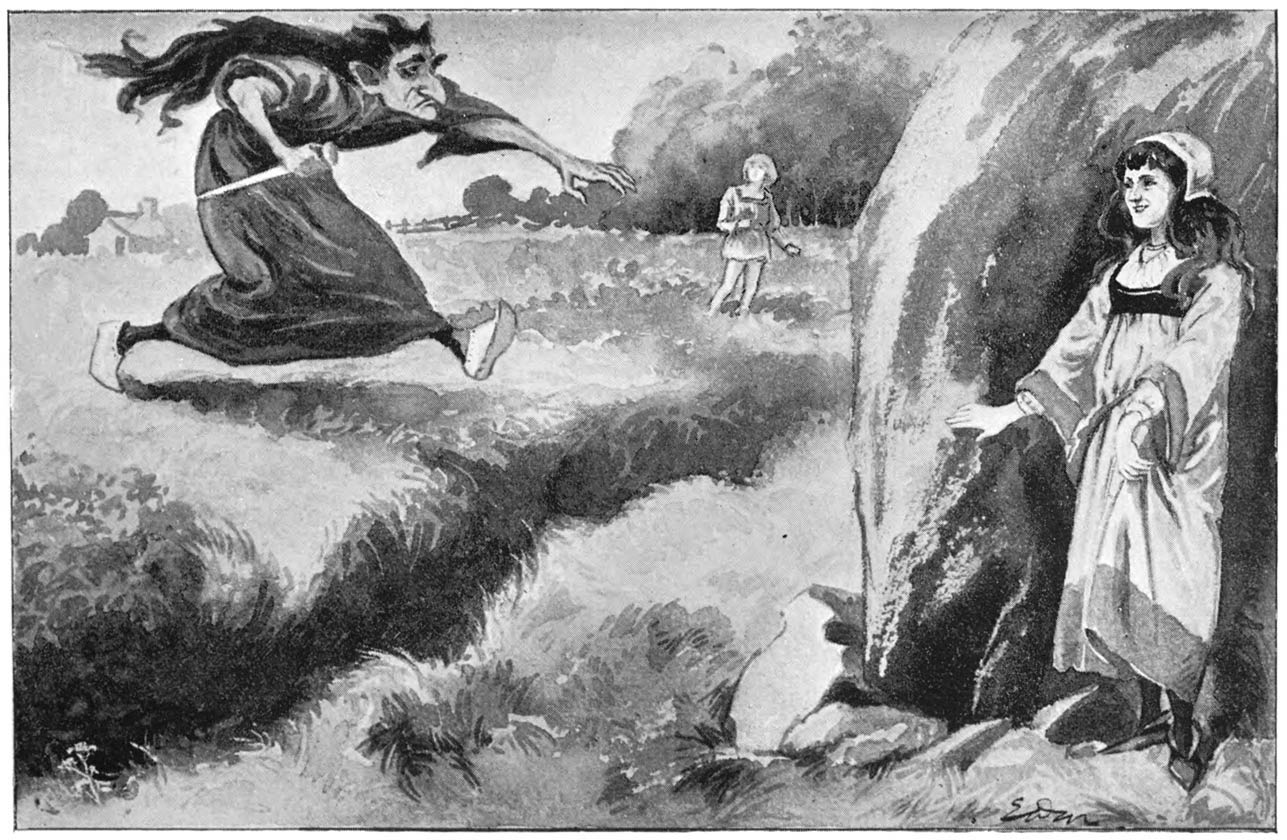

By this time the old ogress had wakened up, and, not hearing a sound, began feeling about for the children. When she had tapped all round and could not find them, she began to scream and swear with rage, and ran out, calling loudly after them.

As soon as Ingibjörg saw her rushing along, her hair streaming wildly behind her, she could not help laughing out aloud.

“Ha! so you are there, you bad wicked children!” cried the ogress. “But only wait, just let me catch you, and I will teach you to run away! You shall be put into the oven at once, for you are quite fat enough now, and then I shall have a good meal!” So saying she ran along the path to where she heard Ingibjörg’s voice, but, unable to see the ditch, she fell in headlong and broke her neck.

“ ‘JUST LET ME CATCH YOU.’ ”

Thorwald did not wait to learn what happened, but as soon as he saw the ogress run after them and fall into the ditch, he took hold of Ingibjörg’s hand, and together they raced back to the shore, very thankful that they were now safe from the old witch’s clutches.

CHAPTER IV.

THE KING’S RETURN, AND QUEEN GUDA’S RELEASE FROM THE WITCH’S THRALL.

Several weeks now passed. Each morning Thorwald first gave a look across the sea in hopes of seeing a ship or boat, and would then start off in search of birds and game, while, strangely enough, after the old witch’s death their fire never went out, and Ingibjörg, by carefully attending to it, was able to keep it burning both day and night.

Sometimes, when no food was needed, the children having laid in a sufficient supply of game and fish, Thorwald would take his flute and play, while his sister plaited mats and baskets out of the long rushes that grew near the shore.

Thus it happened that one day, while the two children sat on the shore, they saw several ships sailing slowly past the island.

Thorwald, who had just put down his flute, now took it up again, and began playing as loud as he could.

The ships came gradually nearer.

“Oh, Thorwald!” cried Ingibjörg, clapping her hands, “see, they are coming nearer! Oh, play louder, louder!” and she joined her voice to his flute.

And sure enough, ere long, the largest of the vessels cast anchor close to the shore, the other ships still keeping out to sea at some distance.

And then, to the children’s great joy, they saw their father standing on the deck. A boat was lowered, the king and one of his followers were quickly rowed to shore, and in a few more moments Thorwald and Ingibjörg were clasped in their father’s arms.

Great was his surprise to find them on this lonely island, for he had heard nothing of what had happened in his own country during his absence, and it was only by chance that he had sailed close to the island, none of his people caring to come near it, as it was supposed to be the home of evil spirits; and when they heard the sound of the flute they thought it must surely be the song of some mermaids, wiling the king’s fleet to destruction by their soft sweet melodies.

But the king for some reason felt he must find out what it was, so had ventured near the land, the rest of his fleet keeping out to sea.

The king then asked his children how it was they were there, and when he heard what had happened during his absence, he grew very wroth.

He at once took the children on board his own ship, and commanded his people under pain of instant death not to breathe a word to any one of what had occurred.

The fleet was then ordered to set sail and return home with all possible speed. Arrived near his own island, the king chose a quiet and retired part of the shore, and there he landed the children in charge of his own attendant, telling him to keep them hidden till he sent him word to appear with them at court.

The fleet then departed and cast anchor at the usual landing-place. Here the queen, arrayed in her richest garments and attended by all her maidens, came down to welcome the king, expressing great joy at his return.

The king appeared well pleased to be at home again.

“But where are the children?” he asked; “and why have they not come to meet me, as they always do?”

“Alas, alas!” cried the queen, putting her handkerchief to her eyes as if to hide her tears, but really because she was afraid to look at the king. “Poor, poor children! Pray do not speak of them! Soon after you went away, they suddenly got very ill, and though I watched and nursed them myself, the poor little things both died!” and Guda began to sob and cry in reality, for she greatly feared what the king might do if he ever heard the truth.

And no one dared say a word; for during the king’s absence Guda, urged on by fear of her mother if she did not get rid of her stepchildren, and also thinking that she could only govern by making herself feared, had ruled the kingdom with great severity, so no one dared say a word against her, believing that the king was still devoted to her.

The king, wishing to get at the truth of the strange tale, pretended great sorrow at the news of the children’s death.

“And where are the poor little things buried?” he asked. “I should like to see their tomb.”

The queen tried to persuade him not to go. She said she was sure it would only increase his sorrow, and entreated him to desist.

But the more she urged him not to go, the more determined he was to see their tomb.

So at length Guda yielded, and herself accompanied him to the wood at the back of the palace, where, in a pretty open glade, she had caused a handsome mausoleum to be erected.

He greatly admired the beautiful carving on the stone, but he never shed a tear, which somewhat surprised the queen. Soon after they both returned to the palace, where the queen had had a banquet prepared to welcome home the travellers.

All during the feast the king still remained very silent and preoccupied, and next morning he again went to the mausoleum, and then said he meant to have the children’s coffins taken out.

When the queen heard this, she threw herself on her knees before the king, and begged and entreated him not to thus further increase his pain and grief. But the king remained firm. The door of the great mausoleum was thrown back, and two small coffins, handsomely ornamented with gold and silver, were brought forth. But, behold, when at the king’s order these were opened, instead of containing the bodies of the two children, they were filled up with stones!

The queen gave a great cry when she saw her wickedness had come to light. She fell down at the king’s feet, and, sobbing and praying for mercy, she confessed what she had done, adding that her mother, the old witch, had forced her to do it.

But the king was so angry that he would not listen to her words, and ordered her to be shut up in the castle donjon till the Volkthing decided what her punishment should be.

Meanwhile Thorwald and Ingibjörg arrived at the palace, the king having sent a messenger for them, and great was the rejoicing among the people when they learnt their young prince and princess, whom they thought dead, were alive and once again among them all.

The children then told their story before the assembled nobles and vikings, and when Ingibjörg related how Thorwald had killed the old ogress, who had only been fattening them up in order to eat them, there was a flash of lightning, and a loud crash of thunder resounded through the great hall. The door at the lower end opened, and, to the surprise of every one, the queen, draped in a long glistening white robe, walked up the hall, and falling down at the king’s feet, she raised her clasped hands towards him.

“Pardon and forgiveness, oh king!” she cried. “The spell that has nearly cost me my life, is at length broken! That terrible old ogress was not my mother, but a wicked fairy who, because she thought my mother had not treated her as well as the other fairies at my christening, condemned me as soon as my mother died, to serve her and obey all her behests as long as she lived. Now that your brave boy has killed her, I am freed from her wicked spells. And now, oh my king, punish me for the harm I have so unwillingly done; but, oh, let me live to prove my gratitude to you and yours!”

Great was the surprise of every one at the queen’s story, and the ambassadors then recalled to mind how silent and grave the young queen had been when they first saw her, even while she did all the old witch ordered her to do.

Thorwald also added his entreaties to those of the queen, and when Ingibjörg with a merry laugh threw one arm round her father and the other round the queen, the king relented. And thereupon the interrupted feast was renewed amid general rejoicing, the queen seated at the king’s right hand with Thorwald beside her, and Ingibjörg on his left hand.

There was no happier