THORSTEIN

CHAPTER I.

HOW THORSTEIN LOST HIS KINGDOM.

There once reigned a king and queen, a long, long time ago, who had an only child, a son called Thorstein.

The lad was brave, strong, and handsome, and was greatly beloved by every one on account of his kind-heartedness and open-handed generosity.

But as years passed and he attained to man’s estate, his indiscriminating kindness was often taken advantage of. His father and mother tried to check him, pointing out that heedless generosity often did more harm than good; but Thorstein could not be brought to believe that kindness could ever be wrong or do harm, and continued to give to every one who asked him, as long as he had anything he could part with.

At length the king and queen died. On their death-bed they again endeavoured to impress upon their son that a good and wise king must not only reign with kindness, but also with justice; but though Thorstein, who loved his parents dearly, and was terribly grieved at the idea of losing them, promised he would do his best and bear their wise counsel in mind, no sooner were the burial ceremonies concluded and he was crowned king, than all his good resolves to be firm and discriminating were scattered to the winds.

He kept open house for all who choose to come, gave gifts to all who asked, so that all the riches and treasure his wise father had so carefully collected began very speedily to disappear, without any one being really the better or happier for them.

So quickly indeed did all he had inherited vanish, that ere many months had passed he had nothing left but the kingdom itself; and then realizing the truth, that a penniless king has but small authority or power, he decided to part with his throne, and thus have some money wherewith to make a fresh start in life.

There was no difficulty in finding a purchaser, and Thorstein, in exchange for a horse and a sack filled with gold and silver, parted with his inheritance.

But when he had once sold his kingdom, his so-called friends, who had been so numerous before, now speedily began to drop off, and as the sack got emptier, so did his companions grow fewer in number.

“There will soon be nothing more to be got out of him,” they said. “A fool and his money is soon parted.” So they gradually deserted him.

Then, when it was too late, Thorstein began to realize the sad plight he had brought himself to, and determined to quit the country, and leave his false friends behind him. He therefore put together the few things he had left, placed them on the horse he had bought, and mounting his own fine chestnut, which he could never bring himself to part with, he started off on his travels.

For a long time Thorstein wandered on over desolate moors and through dark sombre forests, not knowing or caring where he went or what became of him. He had no friends, not a single creature to care for, or who loved him, so he allowed the horses to roam where they listed, letting them graze whenever they came to any fresh grass, but beyond this never resting or pausing anywhere.

Once, when they had stopped to graze near a tiny stream on the banks of which the grass looked specially fresh, he got off his horse, and throwing himself down on the ground almost made up his mind to go no further. Why not rest there till death overtook him? But even as this thought flashed through him, he raised his eyes towards the west, where the sun was just setting in a bed of crimson and gold, flushing all the distant peaks of the great snow-capped mountains with magic rainbow hues.

Whilst still lost in wondering admiration at the gorgeous spectacle, the rosy clouds suddenly parted, and a star of exquisite brilliancy shot down a ray of light that seemed to touch Thorstein’s face, and he heard a voice saying: “Fear not, Thorstein, but go forth on thy travels with a brave heart. Learn from the mistakes of thy youth, that indiscriminate open-handedness is neither just nor kind, but only does harm, and that a true sovereign must also be a father to his people.”

And even as the voice died away, the rosy light gradually faded from sky and mountain, and the pale golden moon rose and shed its soft silvery radiance over earth and sky.

Thorstein started to his feet. He felt the warm blood coursing quickly through his veins; and whistling to his horses, who came obedient to his call, he mounted his noble chestnut with a light heart, fully determined to seek his fortune.

CHAPTER II.

HIS ARRIVAL AT THE GIANT’S CASTLE.

For some time he followed the rough track across the open plain, but presently he arrived at a small farm. Knocking at the door, he asked the old man who opened it if he might rest the night there.

“Oh yes,” replied the man; “if you don’t mind taking things as you find them, you are very welcome.”

Thorstein thanked him kindly, and after stabling his horses in the shed at the back, threw himself down on the rushes that were lying in one corner of the room, the farm servants occupying the opposite corner, and the old man sleeping in a third corner, the remaining one being filled by the huge stove.

Thorstein, tired out with his long day’s journey, slept soundly all night, but when he woke next morning he was surprised to find the farmer and his men had already gone out.

Fearing lest some treachery might be meditated, he sprang up from his bed and rushed out of the house.

There, to his surprise, he saw the farmer and all his men busily at work with their pitchforks, digging and raking up the earth from a large tumulus, or grave, at some little distance from the farm.

Thorstein hurried up to the farmer, and asked him what he was doing, and why he was disturbing the grave.

“I have very good reason for doing so,” replied the man; “the man who lies buried there owes me two hundred dollars!”

“But,” said Thorstein, “no amount of digging will give you back the money he owed you! On the contrary, you are losing your own time as well as that of your men, and you will probably, in addition, get fined for disturbing the grave.”

But the farmer was obstinate. He said he did not care. Only he was quite determined that the dead man should not rest peacefully in his grave, while he owed him all that money, and that he and his men would continue to dig and stir up the ground day after day.

Then Thorstein asked him if he would be satisfied and let the man rest in his grave if some one else paid the dead man’s debt.

“Oh yes!” answered the farmer; “but I don’t see where that man is likely to come from, as he had no sons.”

Then Thorstein drew forth his purse, which contained the last of his money, and gave it to the farmer in payment of the debt. The farmer thanked him warmly, and promised not to disturb the grave any more.

So Thorstein bade his host farewell; but ere he left he asked him which road he should take, so as to reach a populous neighbourhood, where he might chance to get some work to do.

“You must continue along this same road,” replied the farmer, “until you come to four cross-roads. Then don’t take the road that goes east, but take the one that goes west.”

Thorstein thanked him, and rode away. After some time he arrived at the cross-roads, and took the rode to the west, as the farmer had advised him. But he had not gone very far when he thought he would rather like to know why the man had said he should not go the other way.

“Perhaps there are giants or some other dangers one may meet,” thought Thorstein; so he promptly turned back till he arrived at the cross-roads, when he proceeded along the road leading east.

For some time he saw nothing new or strange. The road wound among many small fields and brushwood, with here and there some groups of tall, dark pine-trees; but after passing through a narrow defile, he suddenly came to a large, deep valley, in the centre of which rose a fine big house, standing quite by itself on a steep, rocky mound. At first he could see no way of getting up to it, but presently he noticed a narrow path, almost hidden by trees and thicket; so, fastening his horses to a stake, he made his way up to the house.

As he approached he saw the door was wide open and no one anywhere about. Thorstein therefore went in and came into a big hall, in which stood two huge beds, one on each side, covered with rich silken hangings, while down the middle ran a table, ready laid with two plates, two knives and forks, two great goblets of rarely chased silver, and two large golden flagons of wine. But no one was visible here either.

After waiting a short time, to see if the owners would appear, Thorstein went down the hill again to look after his horses, for he thought he might as well stay the night in the house, even if there were a little danger in so doing. So he lifted the saddles off the horses, tethered them with sufficient length of rope that they could both graze and lie down comfortably, and then took all he needed out of his saddlebags, with his sword, which, after his favourite chestnut, was his most precious possession. Then, giving a last look to the horses to see they were all right, he returned to the house, and going to the kitchen, he brought thence some bread and the meat which was roasting before the fire.

Cutting this up carefully, he placed a good portion in each plate, together with a large slice of bread; he then went to the beds, shook up the pillows, and made them all ready for the night. After this, feeling rather tired, he thought he would lie down and rest. He did not, however, venture to occupy either of the beds, but threw himself down on some mats that lay in a corner, carefully pulling one over him.

After lying awake for some time, Thorstein was just dropping off to sleep when he heard loud underground rumblings. Presently the door was thrown open, and he heard heavy steps crossing the floor.

Then a loud, gruff voice exclaimed: “Some one has been here! but whoever it is, we shall soon put an end to him.”

“No,” answered another voice, “that you shall not do! I take him, whoever it may be, under my protection; I have the right to do this, for it is my turn, and can dispose of him as I like. He came here of his own free will, and has shown himself both able and willing to be useful. He has made our beds, prepared our food, and all has been well done. Let him now show himself and no harm shall befall him.”

When Thorstein heard these words, he once again began to breathe freely, and throwing back the rug he had drawn over him, stood up before them.

The young men were regular giants, both in size and strength, especially the elder, who had taken his part, and who was quite a head taller than his brother.

Thorstein then went to fetch another plate and cup, and shared in the giants’ meal, after which the two brothers retired to their beds, Thorstein again taking possession of his rugs, where he soon fell soundly asleep, never waking till long after the sun had risen.

Then, while they were at breakfast, the elder giant, whose name was Osric, asked Thorstein whether he would stay on with them; that all he would have to do would be to get their meals ready for them and make their beds. He might also keep his horses in their stables; and as to food and wine, Thorstein would only have to tell them what was needed, and they would always keep the larder and cellar filled, so that Thorstein need never leave the hill.

Thorstein said he would try it for a week. At the end of that time the giants were so well pleased with him, that they urged him to remain with them, for a year, at any rate; and though Thorstein found the life rather dull and stupid, he agreed to stop, Osric, the elder giant, promising him a rich reward at the end of his term. He then handed him the keys of all the rooms in the house, except one key, and this the giant always wore fastened to a string round his neck, only taking it off at night when he went to bed.

When the two brothers had gone off on their daily expeditions, Thorstein made a regular round of the house, looking into the storerooms, cellars, and every room except the one of which Osric kept the key. In vain he tried all the keys on his bunch, hoping one of them might open the lock; but in vain. He then tried to force open the door by throwing himself against it with all his might; but in this also he failed.

Later on, Thorstein noticed that Osric always went into this room every night and morning, while Bifrou, the younger giant, waited for him outside. So one day he asked Osric why, when handing him the keys of all the other rooms, he had kept back this one.

“Surely,” he continued, “if you have found me faithful in all you have entrusted me with, you might also trust me with what is in that room.”

But Osric said there was really nothing particular in the room. Thorstein might be quite sure of that, for, having found him so faithful and honest respecting everything placed under his care, they would certainly also have trusted him if there had been anything valuable in that room.

But although Thorstein pretended that he was quite satisfied with the giant’s answer, he made up his mind to solve the mystery in some way.

At length the end of the year arrived, and the two giant brothers, well pleased to have secured so careful a servant, gave him as his wages two great sacks filled with gold. They had never been made so comfortable before, and again begged Thorstein to remain another year.

To this Thorstein would not agree, but said he would remain six months, as he was more than ever determined to find out the mystery of the locked room.

He therefore carefully watched every opportunity, hoping Osric might perhaps by chance leave the key behind him. But the giant was much too careful to do so.

One morning, when Thorstein had risen particularly early, in order to bake the bread, the thought of the locked chamber came constantly before him, and while kneading the dough he kept puzzling his head as to how he could circumvent the giant. Suddenly a bright idea struck him. Creeping softly to the back door, which led into the stable yard, he gave a loud knock, and then ran back as quickly as he could to the room where the giants were sleeping, and asked them, with a scared face (holding the dough he had been kneading in his hands), whether they had not heard some one knocking.

“Oh yes,” they both replied; “we did hear something, but we thought it was you knocking down a chair while you were sweeping.”

Thorstein declared he had not knocked down anything, and added that he was afraid to open the door, for he was quite positive some one had knocked there.

The giants said he was quite right not to open it, for it might be some unfriendly giant; so they got up themselves, and ran to the door to see who had disturbed them at that early hour in the morning.

No sooner had they left the room than Thorstein drew forth the key of the mysterious chamber, which the biggest giant always kept under his pillow at night, and quickly taking an impression of it in the dough he had in his hand, replaced the key in its former place.

When the brothers came back they were not a little put out, for of course they found no one at the door, and declared that Thorstein had only said it in order to make fun of them.

But this Thorstein denied stoutly, and maintained that he had heard some one knocking, and supposed, whoever it was, must have run away.

CHAPTER III.

THE MYSTERY OF THE LOCKED ROOM.

As soon as the giants had gone forth that day to seek for treasure, as usual, Thorstein tried to make a key at the giants’ forge from the impression he had taken in the dough; but many and fruitless were the trials ere he succeeded. Then, watching his opportunity, when the brothers had gone on a long expedition, he unlocked the forbidden door, and entered the mysterious chamber.

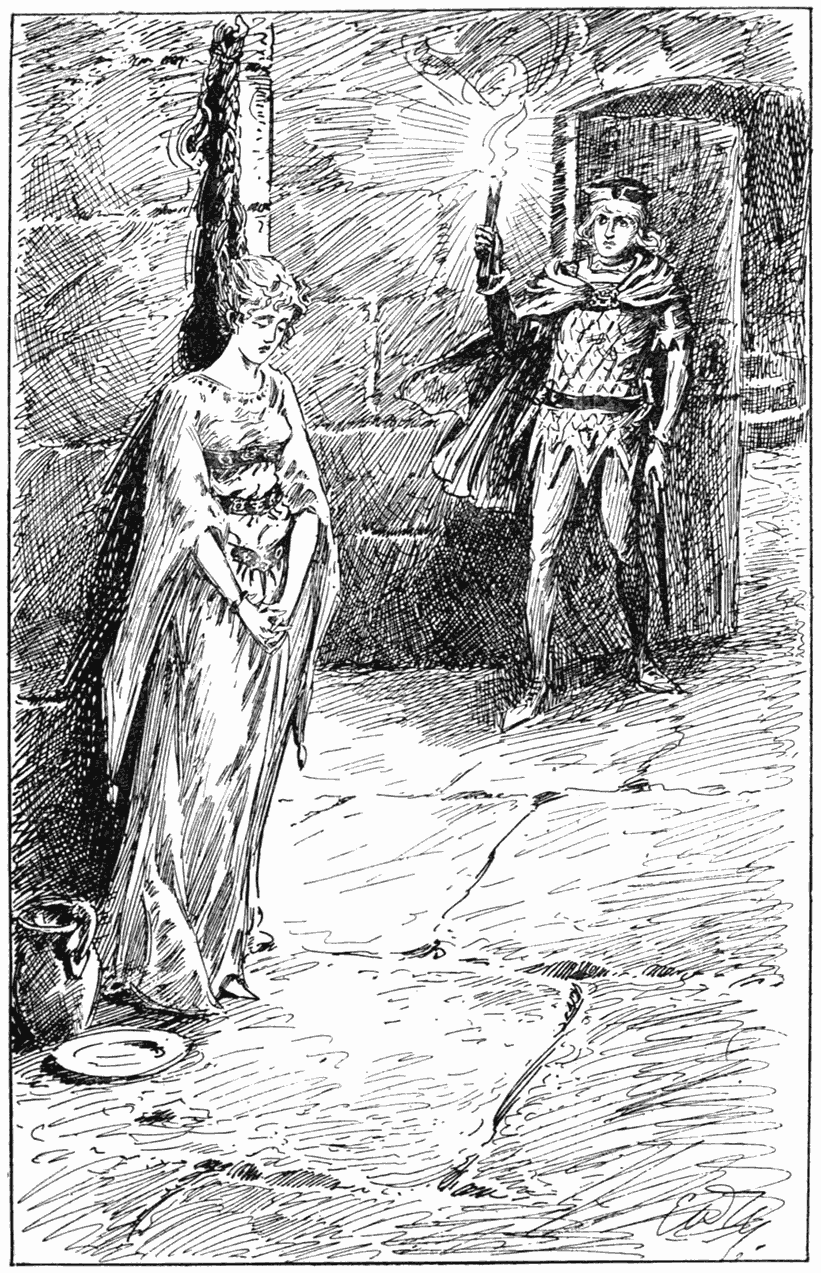

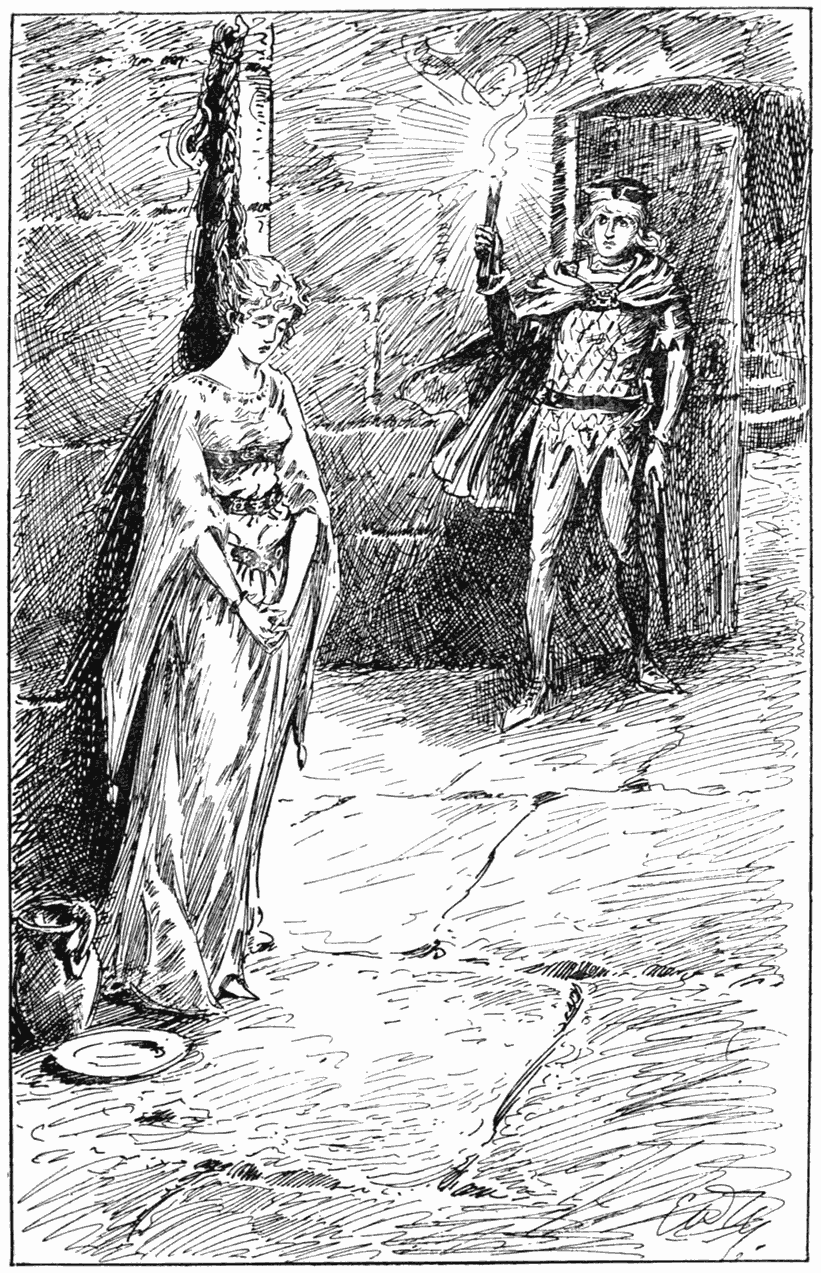

At first he could see nothing, for it was almost dark, the single window being heavily barred and shuttered. But having struck a light, he glanced eagerly round. There, to his amazement and horror, he saw a young girl fastened to a nail in the wall by her long plaits of hair.

Mounting on a chair, he hastened to release her, and begged her to tell him who she was, and how and why she had come there.

At first the poor girl could scarcely believe that she had at last found a friend; but Thorstein looked so good and kind, that her fears quickly vanished.

“Alas!” she said, “I am a most unhappy maiden! My name is Thekla, and my father is King Alfhelm. One day, as I was playing in a field near the palace with my maidens, a great giant suddenly rushed in among us from the neighbouring wood, and snatching me up in his arms, despite all my cries and struggles, carried me down to the shore, where his boat was waiting. Ere any help could reach us, we were well out of sight, till at length we arrived at this place. He then asked me to marry him, which I indignantly refused to do; and though he comes every day to try and persuade me to consent, I will never give in; no, not though they starve or kill me!” And she burst again into bitter sobs.

Thorstein tried to comfort her as best he could. He told her that, having now made a key, he would be able to come and see her every day while the giants were away. He then brought her some food, for the poor girl was half starved (as the giant only gave her just enough to keep her alive), and then, as evening drew near, Thorstein again fastened Thekla’s hair to the nail, ere he closed the door before the giants’ return.

From that day forward Thorstein visited the poor girl regularly every day, always bringing her some food, and then putting all straight again ere the brothers returned, so that they had no idea of what took place during their absence.

“HE SAW A YOUNG GIRL FASTENED TO A NAIL IN THE WALL BY HER LONG PLAITS OF HAIR.”

When the end of the six months drew near, Thorstein told the giants that he wished to leave. But they had got so used to him, and he waited on them so carefully, that they did not want to part with him, and begged him to remain another year.

At first Thorstein refused, but after much persuasion, the brothers giving him again two more sacks of gold as wages, Thorstein said he would remain another six months, if at the end of that time they would give him as wages whatever was in the locked room—no matter whether it was valuable or not.

When Osric heard this he grew very angry, and told Thorstein not to be a fool; that what he was asking for was utterly worthless; and that he had much better accept the good wages they were quite willing to give him.

Thorstein, however, would not give in. He said he did not care whether the contents of the room were valuable or not. He had set his heart upon that, and nothing else, and would remain with them on no other condition.

Osric grew furious, and they argued and fought over this, till at last Bifrou, seeing that Thorstein was quite determined, advised his brother to give in, for they could keep him in no other way. So the big giant at last agreed to his terms.

During the six months that followed, Thorstein did his utmost to lighten Thekla’s imprisonment. Many a long and pleasant chat they had together, planning their future life, while Thekla described her former home, and how delighted her father would be to see her safely back again.

At length the weary six months came to an end; and though the giant brothers again tried to persuade Thorstein to remain with them, he was firm, and would listen to no further promises of future wealth and greatness with which they tried to bribe him.

So, seeing that neither persuasions nor threats would prevail, Osric at last opened the door and brought out Thekla; very much surprised he was to see her looking so well when he saw her in the daylight, and half repented him of his promise.

But Thorstein led forth his two horses, which he had all this time carefully groomed and tended. Placing two sacks of gold on each, he lifted Thekla on one horse, and buckling on his sword, as well as a sharp dagger, mounted the other horse.

As he did so, Thekla noticed the giants whispering together, and heard the younger one mutter, with a laugh, “Yes, as soon as they get to the ravine.”

“Oh, Thorstein,” she said, when they had ridden on a short distance, “I know they mean to attack us. I heard them say so.”

“Never fear,” replied Thorstein. “My good sword has never failed me yet! But you ride on in front.”

As soon as they were out of sight, he placed the other sacks of gold on Thekla’s horse, and bidding her ride on ahead, he drew his sword and kept a keen look-out.

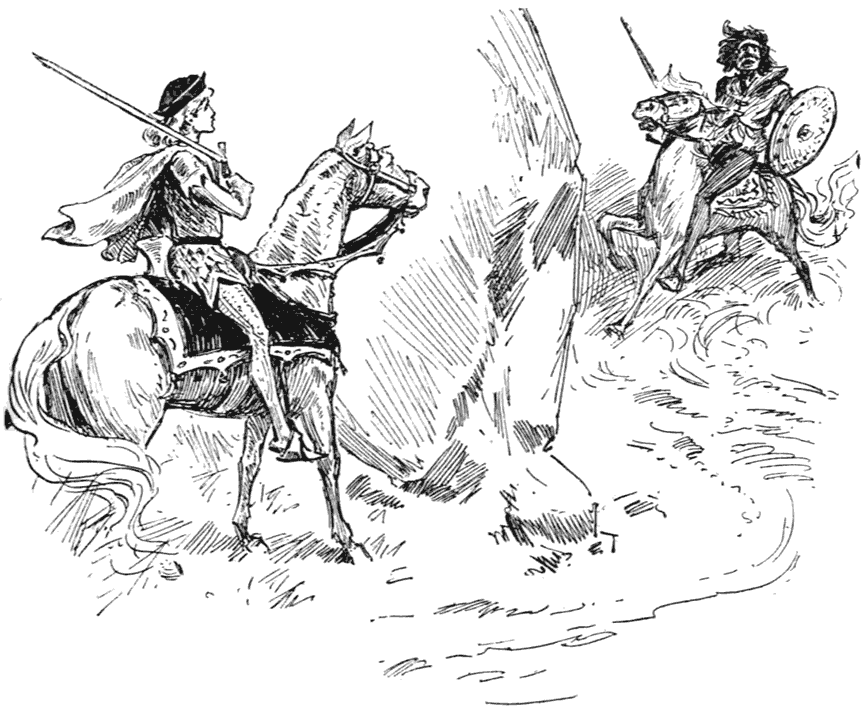

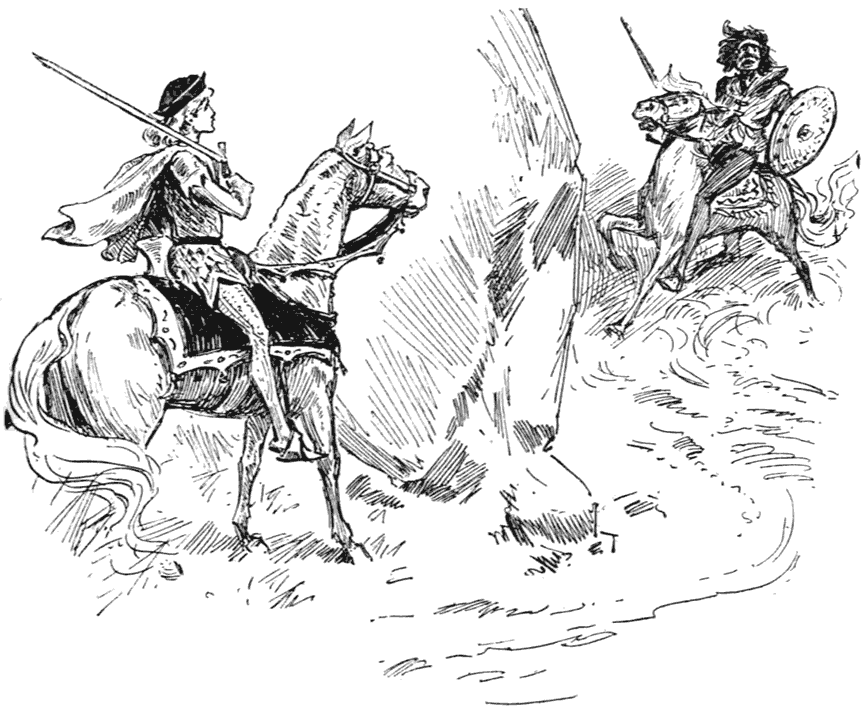

“HE THEN HID HIMSELF BEHIND A PROJECTING ROCK.”

They rode on thus for some little distance. The country was open, and though the road was rough, they were soon out of sight of the castle. At length they arrived at the narrow ravine which led down to the shore. They had not long entered it when they heard the clatter of horses’ hoofs behind them. Thorstein bade Thekla ride on. He then hid himself behind a projecting rock, and as Bifrou, who was in front, rode past, Thorstein rushed at him, and with one blow of his sword, severed his head from his body. Osric, seeing what had befallen his brother and fearing the same fate, rode back to the castle for more help.

Thorstein then joined Thekla, who had anxiously watched the combat, and they rode on, hoping that all danger of pursuit was now over. But just as they emerged from the ravine, Thorstein, looking back, saw Osric, accompanied by a still bigger and fiercer-looking giant, hurrying after them.

Again sending Thekla on in front, he turned and faced his enemies. A terrible combat now ensued. They attacked Thorstein, one on each side, but he swung his great broadsword round his head and with one blow cut off Osric’s head. Then the big giant, seeing his friend fall to the ground, grew furious. He threw away his sword, and grasping Thorstein round the waist, flung him to the ground. But in an instant Thorstein was on his feet again, and now a desperate conflict ensued. They wrestled together fiercely; sometimes one, sometimes the other was uppermost, but at length the giant’s weight and size began to tell, and Thekla was horrified to see Thorstein grow pale and stagger.

Without a moment’s thought or hesitation she sprang from her horse, and, snatching up the dagger that had fallen from Thorstein’s girdle during the struggle, she thrust it through the heart of the giant, who rolled over on his side without a groan.

Both the giant brothers and their friend being now dead, Thorstein said they had better return to their house and take possession of all the treasure they could find. This they did, and by making several journeys backwards and forwards, they had quite a large store of boxes on the shore, filled with gold and precious stones.

Then, to their joy, they one day saw a vessel nearing the land, which, as it came closer, proved to be a ship belonging to Thekla’s father, the captain, called Randur, being one of his chief ministers.

The latter was delighted when he saw Thekla, for her father had been so greatly distressed at her disappearance that he had fitted out several ships to go in search of her, promising that he would bestow her as a bride on whoever was fortunate enough to find her.

Randur therefore at once offered to take them home, and sent some of his men ashore to help and carry Thorstein’s treasure down to the ship. When everything was put on board, the sails were set, and the good vessel sped gallantly on her homeward way.

CHAPTER IV.

HOW THORSTEIN’S KIND ACTIONS RECEIVED THEIR REWARD.

Thekla and Thorstein now thought all their trials were surely over, and gave themselves up to the enjoyment of each other’s society. But Randur had no intention of letting the latter reach Thekla’s home. So he watched his opportunity, and one night, when they were well out at sea, he had one of the boats lowered. In this he placed Thorstein, who was fast asleep in the after-part of the ship, and, casting loose the boat, let it drift away. He then made the men take a solemn oath never to mention what had been done, but that if any one asked about Thorstein, they were to say they knew nothing about him.

Next morning, when Thekla, surprised at not seeing Thorstein, asked where he was, Randur pretended to be greatly surprised at his non-appearance, and instituted a search all over the vessel for him.

Thekla was very unhappy to think that Thorstein should have disappeared so unaccountably; then, suddenly missing one of the boats, she said that perhaps he had gone fishing, and insisted upon the vessel being put about to search for him.

But though Randur pretended to obey her orders, shifting the sails and issuing various commands, he was in reality hurrying home as fast as he could, rejoicing at having so successfully rid himself of his rival.

The boat, meanwhile, in which Thorstein lay fast asleep, had drifted a long distance from the ship ere he awoke, and on first opening his eyes he could not imagine where he was. But when he once realized his position, he decided that Randur’s jealousy must have played him this trick, and he set himself to think what he had better do.

When Randur had sent him adrift, he had put neither food nor water in the boat, and as the sun rose higher and higher in the heavens, the heat grew intense. In vain he steeped his clothes in the water, hoping thus, at least, to assuage his thirst, which was causing him much suffering. He gradually grew more faint and weary, and a feeling of hopelessness was stealing over him, when suddenly he heard a voice saying, “Do not lose heart, Thorstein, though your plight is sad, drifting thus hopelessly about on the ocean. But as you once spent your all to give me rest, so now I will also aid you.”

And immediately the boat flew rapidly over the water, propelled by an unseen force. Thorstein’s thirst and weariness vanished, and he reached the island where Thekla’s father lived at the same time as the ship in which she was returning, though he landed at a different point.

As Thorstein stepped on shore, he again heard the strange voice, saying, “I am only repaying what I owe you, for had you not given up all you possessed to the farmer to whom I was in debt, he would never have allowed my bones to rest in peace in the grave. And now I will help you further. This is King Alfhelm’s country. Go to the palace, and there offer to look after the king’s chestnut horses, of which he is very proud. His late groom was very careless, and has been dismissed, so he will engage you. But, remember, whatever is found beneath the horses’ mangers belongs to you, and you can keep it.”

So saying, the spirit of the dead man departed, and Thorstein, having thanked him gratefully, at once started off for the king’s palace.

King Alfhelm, who had been rather at a loss as to whom to entrust with his fine chestnut horses, of which he was very proud, was greatly pleased with Thorstein’s appearance, and at once put him in charge of the stable, where Thorstein, to his surprise, saw his own chestnut among the other horses—for Randur, on landing, had given it as a present to the king. But the horse would allow no strange hand to come near it; the moment it saw Thorstein, however, it became gentle as a lamb.

The king, meanwhile, was greatly rejoiced at his daughter’s safe return, for he had almost given up all hope of ever seeing her again. So he ordered a great feast to be prepared to celebrate her arrival, and believing Randur’s tale, that he had rescued the princess from the giants, promised to give him his daughter in marriage.

To this, however, Thekla objected.

“Rather than wed Randur, I will remain single all my life,” she said.

This threat so frightened the king, for, having no son, he looked forward to seeing Thekla’s children growing up, that he did not urge her any further.

Thekla then begged her father to summon the new groom to the great hall that evening, for she had been told that he had travelled a great deal, and it would amuse them all to hear his adventures.

So the king, willing to please his daughter, and anxious himself to hear the tale of his adventures, summoned Thorstein to the big hall, where the whole court was assembled.

And then the whole truth came to light; and when King Alfhelm heard the wickedness and treachery of his minister, he grew so angry that he ordered Randur to be torn to pieces by wild horses.

But Thekla and Thorstein both interceded for him, so he was only banished for life from the kingdom.

Very soon after, the marriage of Thorstein and the fair princess was celebrated, amid general rejoicings. In addition to the treasure they had brought back from the giant’s house, Thorstein, on looking under the horses’ mangers, found an immense pile of old go