CHAPTER X

ATTACKED BY COMANCHES

THERE were four men in the party in the grove beside Crockett and Dolph. The two lads made up eight in all.

“Hold your fire,” cautioned Davy Crockett. “Don’t waste any of it, boys; because we’ve got our work cut out for us.”

There were at least twoscore of the savages dashing down upon the grove upon the backs of their hardy mustangs. Crockett had no idea of the marksmanship of his companions. Eight rifles in the hands of men who knew how to use them would work deadly havoc among the oncoming Indians; but if it should prove that the men were not skilled with the weapon, things would not be so well.

But the backwoodsman set his teeth.

“It won’t be long before I know,” said he, grimly.

He threw forward his rifle.

“Ready!” said he.

The other weapons went forward; eight black muzzles peered out at the oncoming savages.

“Fire!” said Crockett.

The rifles spoke sharply; down in their tracks went several of the mustangs; and several others went dashing riderless across the prairie. Shrill yells went up from the Comanches; their ponies, startled at the sudden blaze of fire from ahead, and the fall of their fellows, reared, bucked, and tried to bolt off to one side. The Comanches fought with their mounts and at last headed them around, together, in the proper direction. But by this time the whites had reloaded.

“Fire!” ordered Colonel Crockett, once more.

Again the rifles cracked; and down went more horses and riders in a plunging heap, while the savage band, unable to face the deadly tubes which threw death into their faces, turned and bounded away over the grassy plain beyond range of the white men’s fire.

Crockett rammed a fresh charge home.

“Good shooting,” said he, approvingly. “One way or another, boys, we’ve accounted for a full dozen of the red rapscallions.”

The old Texan, together with the others, was also charging his piece.

“They’re not done yet, colonel,” said he. “The Comanche is a fighting Injun, and it takes a good bit to make him change his mind, once he’s taken to the war-path.”

“I didn’t hear nothing ’bout them being at war with the whites,” remarked one of the men.

“No more did I,” said Dolph. “But, then, you can never tell. They are always rising. Let some rascal of a white man cheat a Comanche at a trading place and that Injun goes and tells his friends. Like as not, a small war follows, until they think they’ve got satisfaction.”

“Well, that might be what this is,” said Crockett, his eyes upon the party of savages which had come to a halt about a half mile out upon the prairie and were listening, apparently, to the eloquence of a chief. “But I’ve got an idea of my own.”

“What’s that?” asked the Texan.

“These redskins had some of their people in Nacogdoches last night and they were watching for some small party that was to leave the town. We happened to be that party. It’s my idea they have taken a leaf from the white man’s book, and are nothing more or less than robbers.”

Old Dolph nodded.

“Well,” said he, “I’ve heard of them doing things like that before now. But, whatever they’re after, they mean to give it another try.”

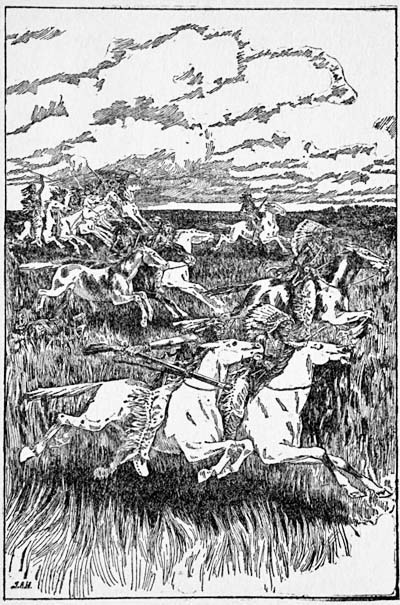

As he spoke the Texan pointed out across the prairie. The Comanches had remounted and were riding forward in an open fashion, their bows and rifles held ready for use. But at some distance from the grove they halted; dismounting, they made their ponies lie down. Then stretched at full length behind this living breastwork, they leveled their guns, and fitted arrows to their bows.

From behind trees and logs, the white men watched the preparations of the savages.

“That is a kind of a cute little dodge,” spoke Crockett. “I never see an Injun do it before.”

Old Dolph nodded and said:

“It’s a favorite trick with the Comanche and the Apache. These Injuns of the plain are ‘horse’ Injuns; and they’re different in their ways from the redskins you meet with in the wooded countries and the mountains. They spend most of their time catching and breaking ponies and learning tricks in riding. There are some fine horsemen on these southwestern plains; but the finest of all are the Comanches.”

THE COMANCHES HAD REMOUNTED

Here the rifles of the Indians spoke. But, if they were excellent horsemen, as the Texan said, they were not good marksmen, for their bullets went wide. Their arrows, however, flew true, and many a feathered shaft struck with a deadly thud into the trunk of a tree behind which stood one of the whites.

A man near Crockett fired, rather excitedly, in return, and the bullet did no more than knock up the dust.

“Take care of your powder,” said Crockett, from behind his tree, but never shifting his eyes from the dry grass where the savages lay behind their horses. “Don’t waste a single charge. Take good aim; and don’t fire until you see the whites of some one’s eyes.”

There was an interval of inaction; the savages were apparently reloading.

“When they have loaded,” said old Dolph, “they’ll take a peep around their ponies to see what things look like over this way. So watch for them.”

“But don’t fire unless you are sure of your Injun,” said Crockett, who knew there was only a limited supply of powder in the party; and as there was no knowing how long the attack would continue, he wished to be as sparing as possible.

Sure enough, as the old Texan had said, when the Comanches had finished loading they showed a desire to know the exact position of their intended victims. A tufted head appeared around the side of a mustang. Dolph’s rifle cracked like a whip; there was a yell of pain and then silence.

“I got him,” said the old Texan, and he calmly reloaded his rifle.

Again came the flight of arrows and the reports of the Comanche rifles; but as before, the shafts and bullets did no harm. Crockett fired when he saw the plumes of a savage show above the back of a horse. It so chanced that the speeding bullet struck the mustang; it leaped up, forgetting its training; its rider was now exposed to the fire of the whites. Three rifles cracked; and the Comanche threw up his arms and sank back.

Seeing the deadly nature of the white men’s marksmanship, the savages grew wary. Only now and then an arrow flew; occasionally a bullet lodged in the ground or in a tree trunk.

An hour passed in this way. It was now almost three o’clock; and Davy Crockett as he crouched behind his tree grew both weary and restless.

“They are cunning varmints,” said he, “and they are holding off until nightfall. Under cover of darkness they’ll creep up on us and beat us down by weight of numbers.”

“Darkness will favor them,” spoke old Dolph. “And if we are here when it falls, we are goners.”

“Well,” said Crockett, in his dry way, “I don’t see how we can get away with thirty pairs of eyes watching us.”

Here Walter Jordan spoke.

“Colonel Crockett,” said he, “I have an idea.”

“Good!” said the backwoodsman.

“We can’t see the Comanches as they lie behind their mustangs,” said the lad. “But suppose I climbed one of these trees. I could have a good sight of them then, and could drive them off with a couple of shots, maybe.”

Crockett smiled and twisted his good-humored mouth drolly to one side.

“That’s a very good plan, youngster,” said he. “But it has one big drawback. How are you going to get up the tree? The redskins would tumble you over before you’d get half-way.”

He saw the disappointed look upon the boy’s face, and added:

“If we were hard pressed and had to do something on the jump, it would be a thing we could try. But, as it stands, I think I’ll make a little experiment that’ll be safe.”

Then turning his head he glanced toward the tree which concealed the old Texan.

“Dolph, who do you reckon’s the best shot in the lot of us?”

“You are,” replied the veteran, promptly.

“Who’s next?” asked Crockett.

“I’d like to say I am,” spoke Dolph, humorously. “But I can’t, and stick close to the truth. Jed Curley’s the best shot here after yourself, colonel.”

Jed Curley was a young adventurer of about twenty-five with whom both Walter and Ned had become very friendly. He was a powerfully built fellow, and his clear eyes and steady nerves gave him the working basis of a sharp-shooter.

“All right,” said Crockett. “Just where are you located, Jed?”

“Right here, colonel,” came the voice of the young man.

“All right. Lie low, but listen to what I’m going to say to you.”

“I’m listening.”

“I’m going to fire at that pinto Injun pony,” said Crockett. “Not to kill it, though; I’ll be careful of that. You see, that pony jumping up a while ago gave me a notion.”

“I see it, colonel,” came the voice of Jed. “You scare up the mustang, that leaves the Injun uncovered, and before he can get shelter, I draw a bead on him.”

“Exactly,” answered Crockett. “Ready, Jed?”

“All ready.”

There was a moment’s silence; then Crockett’s rifle rang out. One of the ponies leaped up with a snort; Jed Curley’s piece cracked instantly and the red rascal behind it lay silent in the grass.

Quickly the two men reloaded; again Crockett fired; once more a wounded mustang uncovered its master; a second time the sharp-shooter’s rifle spoke, and the master lay as silent as the other.

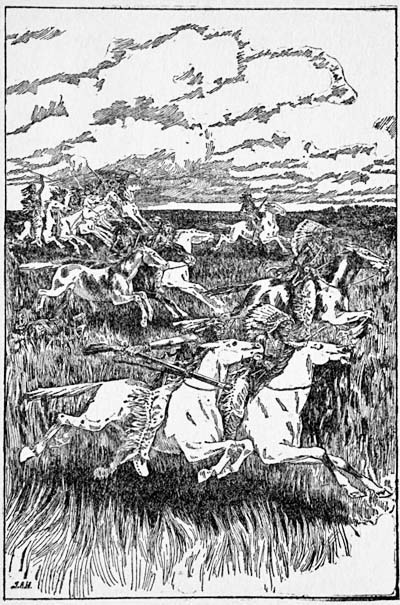

Within twenty minutes this performance had been gone through three times; then a panic seemed to strike the savages; they leaped up, urged their horses to their feet, mounted and turned to flee.

“A volley, boys!” yelled Crockett. “Take good aim.”

The volley pealed from the six rifles that were still loaded, and four more of the Comanches fell. Then the remainder of the band, with startled yells, went flying toward the east.