CHAPTER XIV

THE BATTLE OF THE ALAMO

THE scream and the pistol shot had awakened Mrs. Allison; and when the boys appeared in the doorway with the fainting girl, she was awaiting them.

“Put her down there,” she directed calmly, pointing to a couch covered with a huge buffalo robe.

Under the attentions of Mrs. Allison, who was one of the women of the border, and had been for years accustomed to sudden dangers and calls for help, Ethel Norton quickly revived. In a very little while she had recovered from her fright and was able to talk; and then Bill Hutchinson introduced Walter and Ned, and they told their story once more.

“Oh!” cried the girl, when she had heard it all and realized the nature of the danger she had just escaped, “how can people be so cruel and so wicked! And,” looking from one to the other of them, “how can I thank you all for what you have done for me?”

They were still talking the situation over eagerly when the sound of horses’ hoofs came from the trail. It was the party under old Dolph and Jed.

“They never stopped,” cried Sid Hutchinson as he slid from the horse of Jed, for he had been mounted behind that adventurer. “They fired back at us, but kept right on running.”

“He means,” said Jed, with a laugh, “all of them that were able to.”

“What of Huntley and Davidge and Barker?” asked Ned, anxiously.

Old Dolph shook his head.

“They are among the ones not able to,” said he. “You youngsters need never be uneasy about them varmints any more.”

For about a week after this Ethel Norton was quite ill, and still another week passed before she felt able to travel; and the boys remained in San Antonio watching the preparations going on for receiving Santa Anna and his army; and also preparing for their own long journey across the plains toward the Red River.

Davy Crockett gave them much good advice upon this point.

“Wait a few days,” said he; “I think a party will be going your way and you can join them. And if there is not, we’ll have old Dolph guide you back. We can spare one man, I suppose.”

The boys waited well into the third week; but there was no sign of a party traveling in this direction. So Crockett consulted with Travis, Bowie and old Dolph, and it was decided that they delay no longer.

“You were sent to get the girl to Louisville,” said Crockett to the boys, “and I guess you’d better do it right away. In a country as unsettled as this one is, too much delay is dangerous.”

“But you are going to stay, colonel?” said Walter.

“As long as Texas has a foe out in the open, I’ll stay,” replied the backwoodsman. “Some day I may go back to Tennessee; but that all depends on how things go with me. War, you know,” and he smiled in his droll way, “is a mighty uncertain thing.”

During the remainder of that day the boys, together with the Hutchinson brothers and old Dolph, looked to their arms and horses. A mustang was presented to Ethel by Colonel Crockett; and at noon on the day following the girl, the veteran Texan and the four boys mounted and waved a good-bye to the heroes they were leaving behind—and heroes they were—heroes such as the world has seldom seen.

Upon the day on which the young travelers recrossed the Colorado, sentinels upon a roof top at San Antonio noted the advance of a Mexican force. It proved to be Santa Anna with an army of seven thousand men. The Texans quickly retreated across the river to the Franciscan mission buildings, known as the Alamo. For there were only one hundred and fifty men in the garrison, and they could not hope to face seven thousand in the open.

The Alamo buildings consisted of a church, with a convent and hospital behind it. Then there was a yard enclosed by a stone wall. The entire place was too much for so small a force to defend; so Travis very wisely stationed his men in the church, which was a stone structure with powerful walls and facing the river and town.

“We have fourteen guns mounted on the walls,” said the young North Carolinian as he swept the plaza before the mission with his keen eyes. “And I reckon the Mexicans will know they’ve been in a fight if they ever get within reach of them.”

Behind these cannon the Texan riflemen awaited the movements of the force of Santa Anna. That commander at once grouped his guns in battery formation and opened fire; the defenders of the Alamo replied with their guns; but their deadly rifles were the most effective weapon; with them they picked off the gunners as berries are picked from a bush.

Travis, while the way was yet open, sent out a message to the Texas government asking that aid be sent them. All the time the force of the Mexicans was growing larger. Colonel Fannin set out from Goliad with three hundred men and four pieces of artillery, to the aid of the Texans at the Alamo. But he had little provision, his ammunition wagon broke down, and he hadn’t enough oxen to get his cannon across the river. Fannin at length gave up the attempt and returned to Goliad. However, a bold leader, at the head of thirty-two daring followers, arrived on the night of March first and slipped through the Mexican lines. This was Captain Smith and his little command from Gonzales; and the defenders welcomed them with cheers.

On March fourth Travis sent off a last message to the Texan authorities; this was carried by the brave Captain Smith, who set his comrades’ lives above his own safety. The message said in part:

“... although we may be sacrificed to the vengeance of a Gothic enemy, the victory will cost that enemy so dear that it will be worse than a defeat.... A blood red flag waves from the church of Bexer and in the camp above us, in token that the war is one of vengeance against rebels. These threats have had no influence upon my men but to make all fight with desperation and with that high souled courage which characterizes the patriot who is willing to die for his country; liberty and his own honor; God and Texas; victory or death!”

On the day following the sending of this message, Santa Anna assembled his troops for an assault upon the Alamo; but it was not until the succeeding day that the attack was delivered. Twenty-five hundred troops were divided into four columns commanded by Colonels Duque, Romero and Morales; they had bars, axes and scaling ladders. All the Mexican cavalry were drawn up around the mission to see that no one escaped.

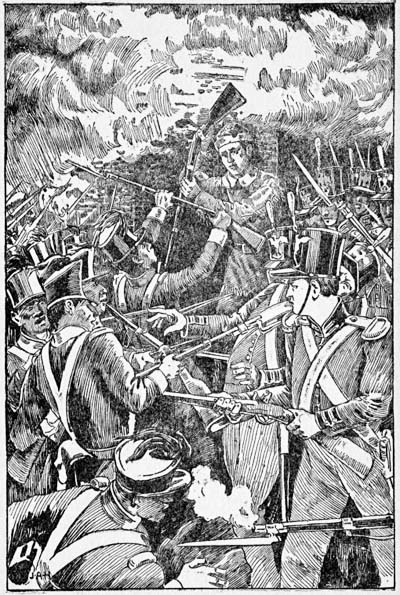

Early in the morning the four columns, at the sound of the bugle, dashed forward; the Texan cannon and the long rifles spat death in their faces. The column under Duque recoiled from the north wall, their commander badly wounded. East and west the attack also failed; the Mexicans swarmed in a shouting mob upon the north side. Their officers shouted and struck at them, forcing them to scale the walls. Once more the sleet of bullets from the American rifles came forth, and once more the attackers fell back. But again the officers forced them to the walls; this time they scaled it and fell over it in crowds. By sheer weight of numbers they forced the Texans across the convent yard and into the hospital.

The captured cannon were turned upon the ’dobe walls of the hospital and smashed them in; a howitzer, loaded with musket balls and broken iron, was fired into the building and the Texans fell like sheep. Then a desperate hand-to-hand conflict ensued. Crockett, Travis and Bonham fought like the heroes of old. Knife, pistol and clubbed rifle played their parts. Jim Bowie had been wounded while defending the wall early in the fight. He lay upon a bed, coolly firing one pistol after another as the Mexicans showed themselves. But he was finally killed by a musket shot.

A DESPERATE HAND-TO-HAND CONFLICT ENSUED

From room to room fought the Texans, contesting every step of the way; the proof of their desperation is the great number of Mexicans who fell in this bloody close-quarters fight; forty-five bodies were counted in one spot after all was over.

Travis fell here, and so did the brave Colonel Bonham. With his loved rifle clubbed in his hands and with many a foeman stretched beside him, fell that gallant Tennessean, Davy Crockett, defending a doorway. Like fiends, the Mexicans, urged by the bloody minded Santa Anna, stabbed and shot, and when the fight was done, every Texan in the Alamo was dead.

News traveled slowly in those days and the boys had reached the Mississippi once more, they had said good-bye to Sid and Bill Hutchinson and Dolph, and were about to embark upon a steamboat for Louisville, when a New Orleans newspaper caught their eyes. And in it they saw the first news of the fall of the Alamo, and of the noble death of Colonel Crockett.

Ethel Norton was as shocked at the news as they were, for the boys had been telling her of the backwoodsman’s good nature and rare qualities of heart.

“And to think,” said she, the big tears starting in her eyes, “that all his high hopes should end in death.”

“But it will not be for nothing,” said Walter Jordan. “Men like Colonel Crockett and Travis and Bowie do not die this way without making a stir. Who knows but their death will so arouse Texas and the Texans that they will not wait to be attacked—that it may make them carry the war to Santa Anna, and so set their country free.”

And it was not long after the three had arrived in Louisville, and Ethel Norton with the services of the elder Mr. Jordan had proved her identity, that news from far-away Texas showed Walter’s judgment to have been good. Texas had declared herself free; Santa Anna had marched another army against her, and was met by a force under the celebrated Sam Houston on the San Jacinto River. The Mexicans were utterly defeated, Santa Anna was a prisoner, and the Lone Star flag had taken its place among the emblems of the world.