CHAPTER XVI

“IF I WERE A WOMAN”

WE had been together about half an hour, discussing eagerly the news which Spernow had brought, when Zoiloff arrived. His face showed that he too had passed anxious hours since we parted. I received him with a laugh and rallied him upon his looks, and then told him the news.

He had not the same intense personal interest in it that I had, and he received it very differently; though his friendship made him understand my feelings.

“It is her first step,” he said, gravely. “We must act warily.”

“A necessity for others besides ourselves,” I retorted.

“It is not certain what form his hostility will take. He may not care to quarrel openly with you, Count; although, if he does, you know he is not a swordsman to be taken lightly.”

“He would serve me no ill turn were he to send his sword through my heart,” I answered, and meant every word I said.

“That would be an ill enough turn for us, though.”

“Let us go to the gallery and see. I have scarcely closed my eyes all night, and when Spernow came he found me hipped and down. It will be a good test for my nerves. If I can hold my own against you under such conditions, we need not be doubtful about this other affair.”

In a few minutes we were busy with the foils, and I told Zoiloff to try with all the skill at his command to beat me. For myself, I tried to make myself believe for the moment that he was the man whom I might have to meet, and I put forth every effort. I never fenced more skilfully or with more spirit, now limiting myself only to defensive measures and now forcing the attack with vehement and even fiery impetuosity.

“I cannot hold you, Count,” said Zoiloff, at length; “I have not touched you once, except that graze on the leg, and you have had me three times badly. If this were in earnest I should be a dead man. But, remember, you know my work now, and that I am not the Duke’s equal with the sword.”

“I must take that risk, and shall not take it without pleasure, I assure you.”

“But that’s not the only risk to be taken.”

“You are in a despondent mood, my friend,” I said, for I knew he referred to what General Kolfort might do afterwards. “Let’s meet them one at a time. This one faced and overcome may mean much to us; and, at any rate, will put us in good heart for what may follow.” My spirits were now as high as previously they had been depressed, and once again I was full of fight.

Zoiloff told me what he had already done to expedite our plans, and when I went to do my regimental work even the knowledge of what I had to tell Christina she must be prepared to do had become less oppressive and disheartening.

On my return home, however, I found a note from Mademoiselle Broumoff, asking me to see Christina at once. “General Kolfort has been with her this morning, and something passed which has upset the Princess extremely. Although she has not told me that she wishes to see you, I am sure of it. Don’t mention this letter.”

This alarmed me, and early in the afternoon I was at her house. I found her looking troubled and agitated, and so pale that I was filled with concern. She received me as graciously as usual, but I could detect a touch of shrinking reserve.

“I hope you have no ill news; we cannot, of course, expect a big scheme like ours to go forward without an occasional check,” I said.

“There must be no check—none if I can prevent it, that is.” She spoke very sadly, and then forced a smile to her face.

“You have had some news, I see,” I said after a pause.

“Yes, I have bad news; I have had General Kolfort here.”

“His visit was probably the outcome of yesterday’s event.”

“Have you come to upbraid me with what you think my weakness?” she cried quickly, with a swift glance of reproach.

“No, indeed not. But when the Countess Bokara left me she declared with all the malice in her that she would do her utmost to ruin us all. I judge that she has commenced—that is all.”

“She cannot ruin us. Let her do her worst.” It was easy to see, however, that the first blow had been a telling one. Then a thought struck me.

“I think I can tell you the purport of General Kolfort’s message,” I said quietly. “He is anxious to push forward a certain step in his plans to bind you to him. I mean, of course, your marriage.”

Her face grew scarlet, and I guessed it was at the remembrance of the bluntness with which the General would have told her what he had heard about us. I could judge well enough the way he would speak.

“Have you seen him?” she asked after a pause.

“No; but I foresaw what must happen,” I answered gently. “It was inevitable. The only practical proof you could give him of the falseness of the rumour that that woman has set abroad.”

She locked her fingers tightly together, and her face was drawn and troubled. My heart ached for her. Remembering my own sorrow, I could gauge the bitterness of hers. Presently, in a low tone of despair, she said:

“The marriage is to take place in three days;” and, hiding her face then in her hands, she abandoned herself to emotions which she could no longer control. I turned to the window and looked out, that she might have time to regain some measure of calmness.

Presently I heard the rustle of her dress, and I turned round and went back to her.

“You have caught me in a moment of weakness, Count,” she said, smiling through the cloud on her brow and in her eyes. “I think you had better leave me.”

“I came prepared for the news. Indeed, I came to tell you myself that you must be ready to hear it.”

“I would rather have heard it from you;” and she smiled wearily. Then, laying her hands impulsively in mine, she said sweetly but mournfully: “It is hard to inflict sorrow like this, and I do not hide from myself, dear friend, that this must give you pain. Believe me, that thought is not my least grief in this. If I were only a woman,” she cried, with a deep sigh.

Her words and tenderness almost unmanned me. I had no words to reply, but stood still, holding her hands in mine and meeting her gaze with glances that spoke the love I felt.

“I have no thought but for your happiness,” I murmured at length.

“Happiness?” she whispered; and her eyes closed an instant as she drew a deep breath as of unbearable pain. Then she mastered her emotion. “I must never see you alone again, Count. I ought not to have seen you now, but—I am a woman. I felt I must thank you once alone, and tell you how it wounds me to wound you thus. Others may think of me as ambitious, cold, unwomanly, selling myself for a throne, a heartless creature without the attributes and qualities of my sex. But you will know the truth. You must know it, even if I bare my inmost heart in telling you. You will not think ill of me, though I have made you so poor a requital for all that you have done and would do for me. Do you think I am seeking my happiness in this?”

“Forgive me that word. If I know what you are suffering in this it is because my own heart tells me; and I dare not utter all that it tells me.”

“You are a strong man and will fight it down.”

“I shall never forget,” I cried earnestly, my voice hoarse with passion. “And never again so long as my heart beats will it hold a feeling such as that which fills it now.”

This pleased her, and she smiled sweetly and tenderly, while the clasp of her fingers tightened on mine.

“Would God it could have gone otherwise for us,” she breathed, her eyes lingering lovingly on my face, with infinite sadness and yearning.

I carried her fingers to my hot lips and kissed them fervently.

“Go, go,” she cried passionately at the touch of my lips. “Go, or I shall bid you stay, let the consequences be what they will.”

I looked up into her radiant face, now fired with her passion.

“One touch of your lips, if only to ease my suffering.”

The ruby colour flowed rich and deep over her face, and, bending forward, she kissed me on the forehead.

“Go, in pity for me, go,” she cried, excitedly.

One moment longer I stood, gazing at her with my soul in my eyes, feasting my senses on the signs of her love, and then I tore myself away. A last glance as I left the room showed me that she had thrown herself back in her chair with her hands clasped in front of her face.

I rushed back to my house, my head bewildered and dizzied with the sweet delirium of her avowed love, and I sat like a crazy loon for hours, running over and over again in thought all the incidents of the scene.

She loved me. Nothing could rob me of the sweetness of that knowledge. All else that could happen was as nothing compared to that. The plot might succeed or fall; she loved me. Bulgaria might be free or enslaved; she loved me. The Russians might triumph or fail; she loved me. It was the one balm for every sorrow, one true note of joy in every trial: she loved me; and I was mad with the delight of it all.

In the early evening Spernow came to me; and then I remembered with an effort—for all memory was swallowed up in the one delicious remembrance of her love avowal—that I had promised to go out with him. I did not care whether I went or stayed; what I said or did, all was alike indifferent to me; but when he urged me, I dressed and went with him. As we drove along he said something, however, which brought my intoxicated wits together.

“Duke Sergius will be here to-night, Count. We shall see what he means to do.” I laughed so loudly that he looked at me in surprise. What cared I for the Duke Sergius? I carried a charmed life, for Christina loved me. He might marry her: but it was I had her heart. If he killed me, he could not alter that. And whether I lived or died mattered nothing now. I hoped he would quarrel with me. “To be married in three days.” Marriages are not made with the dead, my lord Duke, I thought, and laughed again.

“If he wants to quarrel he will find me ready enough,” I said, boastfully and noisily; but before I entered the house I had put a restraint upon myself and wore my usual reserve, covering up that mad, wild, whirling passion that was heating every vein in my body. I soon saw, too, there was a cause to be wary.

“His friends are in strong force here,” muttered Spernow, as together we entered the room and were greeted by our host, a man named Metzler, who led us forward chatting pleasantly about nothing.

There were about a dozen of us in all in the room, and the first glance showed me that it was intended to be a wet, wild night. Three or four of the men I knew to be dare-devil scapegraces, hard drinkers and harder players even for that city of hard drinking and high gambling, and it was easy to see by their faces that some of them had made haste to begin, for they were already flushed and excited. It was the kind of party where an empty glass was considered a sign of discourtesy to the host.

The Duke was gambling, but saw me enter, and when I approached him gave me no more than a surly nod in place of his customary rather effusive greeting. I augured well from this, but was careful to be particularly courteous.

In a few minutes Spernow and I were seated at a table playing some silly card game or other for fairly high stakes. I felt no interest in it, and cared not one jot whether I won or lost. I staked moderately and drank very sparingly, finding my amusement in watching the flushed eagerness of the men about me; the noisy laughter when they won, and the muttered oaths when fortune went against them.

I glanced now and again at the other tables, and I noticed that the Duke was in much the same mood as myself, and twice caught him scowling angrily and darkly at me. Each time I laughed in my heart and smiled pleasantly with my lips.

“Fortune with you, Duke?” I cried the second time.

“My turn is coming,” he answered, with an expression that in a dog or a wolf you would call a snarl.

“Well, don’t be afraid to back it when it does come. I’m winning,” I said with another smile, as though cards were the one absorbing thought in my head just then. But he seemed to put his own interpretation on my words, for he answered in a surly tone:

“Ah! your luck may change;” and he turned to his game again.

After an hour or two a halt was called for supper, and I observed that the Duke scrupulously avoided me. I noticed, too, that he had begun to drink much more freely, and while I chatted with the men about me I kept a close watch upon all that he did.

As soon as supper was finished the glasses were refilled and the gambling began again.

“Thank Heaven that’s over; now we can settle down to business,” said one of the men near me, who had been a high player and a heavy loser; and that voiced the thoughts of most men in the room.

An hour later I noticed that Spernow was infected with the mania for high play. He was staking large amounts, which I knew he could not afford to lose, and he was losing them. I gave him a warning look or two, but he would pay no heed; and to create a diversion I declared that I had played enough. It was all to no purpose, however. It did not check him, and it irritated the men about us.

For that I cared nothing, but it brought the crisis for which I had been waiting. The men were urging me to continue, and I was refusing, when I heard the Duke say to a man at his table, in a voice intentionally loud enough to be heard by all:

“Nothing like cards to test a man’s pluck;” and he accompanied the words with a sneer and a shrug of the shoulders.

I would not take the words to myself, though I knew, as did the rest, that they were flung at me.

“I would rather not play again,” I said to those about me.

“I don’t suppose we are to stop, gentlemen, to please one man’s caprice—or cowardice, or whatever you call it,” said the Duke insolently.

“You will not mind if we resume, Count?” said our host, nervously, trying to fill the awkward pause that followed the words.

“Not in the least,” I answered, pleasantly, for all the anger that began to stir in me. “I will look on.”

“No, no, Metzler,” cried the Duke noisily. “I object to that. Lookers-on can see too much and can make use of their knowledge. If Count Benderoff is too careful of his money to play, you should ask him to retire.”

“That is the third unpleasant thing you have said about me in as many minutes,” I said, turning pointedly to him, but speaking coolly.

“Is it?” and he laughed insolently. “Well, you’re doing a deuced unpleasant thing, and I suppose I may express my opinion.” This time two of the other men sniggered.

“I have merely expressed a wish to play no more.”

“And you do it with an air of a highly virtuous priest with a mission to teach us how to behave ourselves. We don’t want you Englishmen or Roumanians, or whatever you please to call yourself, coming here to set up any canting standard of morals. We can look after ourselves,” he sneered, his face flushed and his eyes glittering angrily.

The situation was fast growing serious, and every man stopped to watch us two.

“I have done nothing of the kind, as you and these gentlemen know quite well. It seems that you wish to insult me wantonly.”

“Do you mean to say that I don’t speak the truth, Count Benderoff?” he cried, rising and coming towards me.

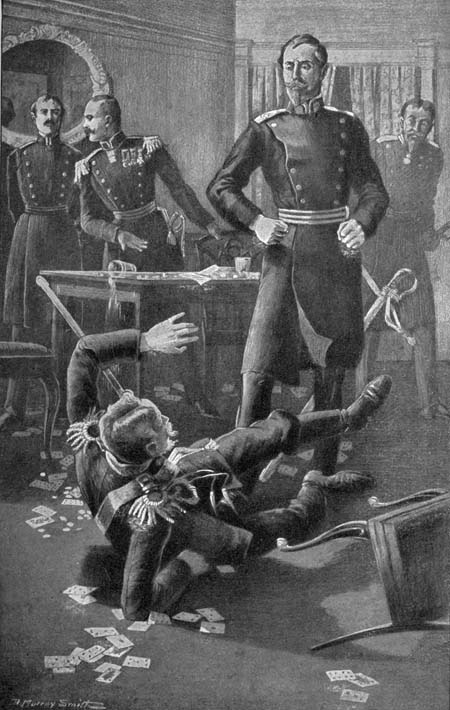

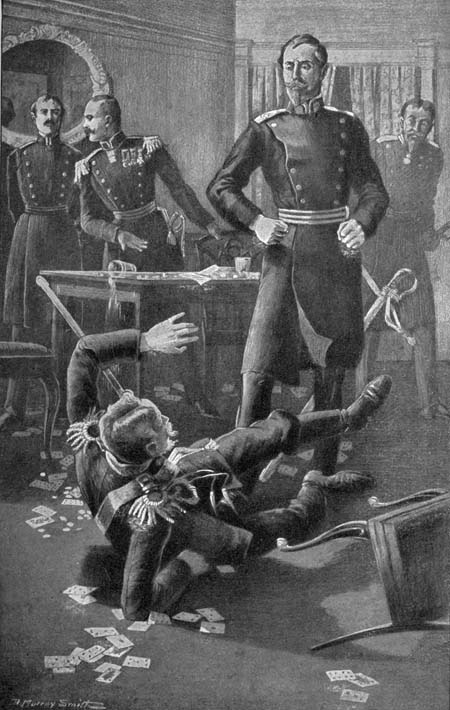

“I STRUCK HIM A VIOLENT BLOW AND KNOCKED HIM DOWN.”—

“Gentlemen, this has surely gone far enough,” said Metzler, his face pale, as he put himself between us hurriedly. “The Count has only expressed a desire not to play any longer, and, of course, in my house I should not think of urging him;” and he glanced at the rest, as if asking them to interfere.

“Our host’s views are my answer to you,” I said.

But the Duke was bent on the quarrel.

“A very discreet shield,” he sneered, and then his passion broke out. “What I said I maintain,” he continued furiously. “You have tried deliberately to break up the party with your infernally domineering interference. I have had far too much of your interference, not only here but elsewhere. I’ll have no more of it. Who are you, to come thrusting yourself into concerns that are nothing to you? If you don’t like our company, leave it; and if you don’t like the country, leave that too. And the sooner the better. This is no garbage-heap for either renegade Roumanians or cowardly English to be carted here;” and he laughed in my face.

My blood boiled at his words, but I meant the quarrel to go even farther yet, and after a pause of dead silence I answered, clipping my words short:

“Rather a hunting-ground where a fortune may be picked up by any drunken, bankrupt Russian duke, infamous enough to stoop to any cowardly baseness.”

He could scarce restrain himself to hear me out before he flung himself at me in wild, desperate rage.

I caught his arm in my left hand as it was raised, and flinging out my right with all my strength I struck him a violent blow on the mouth and knocked him down.

In another moment the men had thrown themselves between us, holding him as he struggled to his feet and drew his sword, striving to get at me and cursing wildly.

I was as cool now outwardly as if nothing had happened, and in my heart a feeling of almost wild exultation throbbed and rushed.

“You are all witnesses, gentlemen,” I said to the men near me, “that from the first this quarrel has been forced upon me. Lieutenant Spernow, for the present you will act for me.”

“I will have your life for this!” cried the Duke, mad with rage.

I made no reply. There was nothing more to be gained by any further taunts.

“I am sorry this has happened here and to-night,” I said to my host. “But you must have seen it was none of my seeking. You will excuse me if I go.”

I left, and walked home with a feeling of rare pleasure at the thought of the coming fight. If I did not punish him for his foul insult, then surely was I what he had said—a coward.