CHAPTER XVIII

THE FIGHT

AS I dismounted I saluted the others and glanced sharply at the Duke, who feigned not to notice my salute, and looked away without returning it. I hoped I could detect an expression of genuine anxiety on his face, as if he did not at all relish the turn things had taken; and purposely I assumed as dark and stern an expression as I could force into my face. Though I was debarred from killing him, I would at least act as if I meant to.

It did not take much time to select the place and complete the necessary preliminaries, and while I was making ready I drew Zoiloff aside.

“I must have a last word with you, my friend,” I said earnestly. “Matters have taken a strange turn since I saw you; I have had an urgent request from the Princess not to kill the Duke, and I don’t hide from myself that I am now going probably to my death. If I am to act only on the defensive, I can’t carry on the fight indefinitely, of course; and, if I fall, I charge you on your honour to let the Princess know that my last thoughts were of her.”

He saw instantly how grave the prospect was, and was more moved than I could have believed.

“We have arranged that it shall be to the death, Count. She had no right to make such a request. Not knowing the conditions, such a request cannot, and must not, be listened to. She cannot wish your death rather than his. Women don’t understand these things. You must not be bound.”

“I have reasoned it out in my own way,” I answered with a smile, “and I shall observe the condition.”

“By Heaven, I would have had no hand in it at all had I foreseen this. But I suppose she does not wish you to be killed like a sheep, without an effort,” he cried excitedly. “You can wound him, at any rate. But die you must not. We cannot spare you, Count; she cannot, she does not, know what she asks.”

“When you think it over calmly you will see she is right. He must not die by my hand, things being as they are.” He knew what I meant, and had no answer to it. He wrung my hand, much affected; and, after a moment, growled into his moustache:

“Hang the women; they spoil everything.”

“Remember,” I said, warningly, “if things go badly with me, give my message—but no reproaches. She must know nothing except that I was beaten by the Duke’s superior skill. On your honour, Zoiloff?”

“On my honour,” he answered; and, as I was ready, we went forward together.

The Duke eyed me with a look of hate, and it was easy to see he meant to do his worst. As our swords crossed, and we engaged, I seemed to feel the thrill of his passion, as if it were an electric current passing through the steel.

He fought well and cleverly, but he was not my match. I had been trained in a better school, and held him at bay without much difficulty. I was much cooler, too, than he; and his fiery temper made him too eager to press the fight.

He made no attempt to wound me slightly, but sought with the vindictiveness of passion to get through my guard and thrust his blade into my heart. My fighting was all defensive; and after a short time my tactics evidently puzzled him. He thought my object was to wear him down. This cooled him, and he began to fight much more warily and cautiously, and with far less waste of energy and strength.

The first point fell to me, partly by accident. Making an over-zealous thrust at my body, which I parried with some difficulty, he came upon my sword point, which just touched his body and drew blood. The seconds interfered; his wound was examined and found to be slight, and we were ordered to re-engage.

In the second bout he changed his tactics, and again attacked me with great impetuosity. The result was what might have been expected. He gave me more than one chance which I could have taken with deadly effect; and when he saw that I did not—for he fenced well enough to understand this—I saw him smile sardonically. He might well wonder why I should wish to spare him. But each time Christina’s words were before my eyes and ringing in my ears, and, bitterly though I hated him, I dared not, and would not, kill him. Then he wounded me. He thought he had found the opportunity he sought, and his eyes gleamed viciously as he lunged desperately at my heart. I parried the stroke, but not sufficiently, for I felt his sword enter my side, and for a moment I thought all was over.

But when the fight was stopped for the second time it was found that the blow had gone home too high, and had pierced the flesh above the heart, and close under the shoulder. The blood made a brave show, but there was no danger—nothing to prevent my fighting on; and again we had to engage.

It was now with the greatest difficulty that I could restrain myself to act only on the defensive. The triumphant gleam in his eyes when his sword found its way into my body had sent my temper up many degrees. A man of honour, having such skill of fence as he possessed, and seeing that I was making no effort to attack him, and was, indeed, actually letting pass the openings he gave, would have refused to continue a fight on such unequal terms. But he grew more murderous the longer we fought, and more than once made a deliberate use of my reluctance to wound him by exposing himself recklessly in order to try and kill me. He did it deftly and skilfully, with great caution, step by step, as if to assure himself of the fact before he relied and risked too much upon it; but, having satisfied himself, he grew bolder every minute.

It was no better than murder; and, strive as I would, remembering Christina’s words and seeking to be loyal to her, I could not stop my rising temper nor check the rapidly growing desire to punish him for his abominable and cowardly tactics. As the intention hardened in my mind, so my fighting changed. My touch grew firmer, more aggressive; I began to press him in my turn, and to show him the dangers that he ran. He read the thought by that subtle instinct which all swordsmen know, and, as my face grew harder and my eyes shone with a more deadly light, I saw him wince, and noted the shadow of fear come creeping over his face and into his eyes. He began to fight without confidence and nervously, dropping the attack and standing like a man at bay.

I pressed him harder and harder, my blood growing ever more and more heated with the excitement of the fight; Christina’s words were forgotten; and springing up again in my breast came that deadly resolve of the previous night to kill him. He read it in my face instantly, and it drove him to make one or two desperate and spasmodic attempts to get at me; though I noticed with a grim smile that now he was cautious not to expose himself as before.

I defeated his attempts without difficulty, and was even in the act of looking out for an opening to strike, when the remembrance of my pledge, and of what my love would say to me if I killed him, shot back into my mind, and at a stroke killed all the desire to kill. The change of mood must in some way have affected my fighting, as we know it will, for I left myself badly guarded, and like a dart of lightning his blade came flashing at me.

I was wounded again; but, fortunately, malice, or fear, or too great glee, made him over-confident, so that his aim was awry, and, instead of piercing my heart, his sword glanced off my ribs, inflicting another flesh wound, but barely more than skin deep.

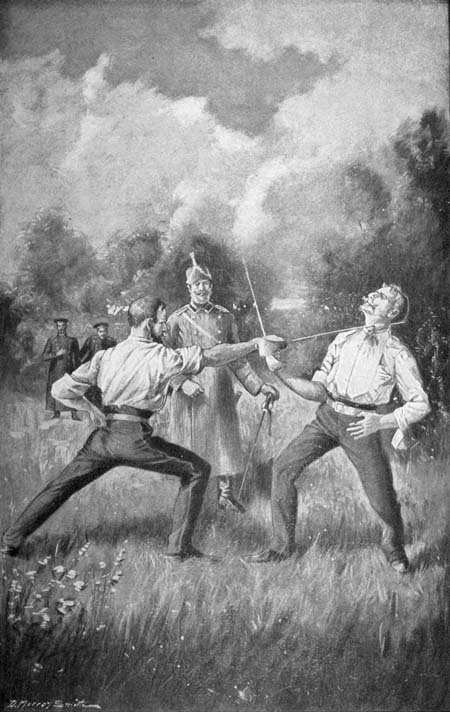

“I RAN MY SWORD THROUGH HIS NECK.”—

“This can’t go on,” growled Zoiloff in my ear, during the pause. “You could have killed him half a dozen times. We shall be here all day.” The absurd bathos of the speech made me smile, despite the grim situation, and the smile was still lurking on my face when we crossed swords for the fourth time. A glance at my opponent’s face was enough to kill any smile, however; and almost as soon as our blades touched he commenced again to force the fight as though he meant to finish it off quickly. So vehement was his attack, that for a while I needed all my nerve and skill to defend myself; but I contented myself with defensive tactics—for the interval had cooled my temper—until, by a little dastardly, unswordsmanlike trick, he tried to catch me at a disadvantage. In an instant my passion flamed up beyond restraint, and before there was time for me to regain control of my temper, an opening came in his guard, and, unable to stay the fighting instinct to take advantage of it, I ran my sword through his neck.

The blood came gushing out in a full crimson stream from the wound and through his parted lips, dyeing his shirt front; he staggered back, his sword dropped from his nerveless grasp, and he fell to the ground with a groan.

I looked on more than a little aghast at my work. If he should die! And at the thought the picture of Christina’s face as she would meet me flashed before my eyes, and for the moment I would have given all I was worth to have called back that laggard thrust.

Zoiloff and Spernow came and stood by me, as I waited, sword in hand, to know if the fierce combat was to go on still further. Then his chief second crossed to us, and in a formal tone said:

“My principal can fight no longer.”

“Is the hurt dangerous? Will he die?” I asked, and the man glanced at me in evident surprise at the concern in my tone.

“Not necessarily. The wound is severe, but the doctor says the artery has not been touched.” Then after a pause he added, as if in involuntary compliment to the skill I had shown: “It is surprising that the fight lasted so long, Count Benderoff. I can bear witness that he owes his life to your forbearance.” And with a bow as formal as his tone he went back to the others.

“We may go,” said Zoiloff; and I handed him my sword and then dressed.

“I am glad you wounded him. I feared you were going to let him kill you. He tried his utmost, and you had one very narrow escape,” said Zoiloff. “But now, where are we to go?”

“I should like first to make quite certain about the nature of his wound. Will you question the surgeon yourself? Spernow and I will wait by the horses.”

“What of your own wounds? Won’t you have them dressed? Better run no risks.”

I had almost forgotten them in my excitement, but I agreed; and as soon as the surgeon could be spared from his attendance on the Duke he came and dressed them rapidly. The one was a mere scratch, and the other not by any means serious. I had been lucky indeed to escape so lightly. “A couple of days’ rest for the arm would be enough,” declared the doctor, who was inclined to be garrulous about the affair until he found that I made no response.

When he had finished with me, however, I questioned him as to my opponent’s condition. He gave me a learned and technical description of the exact character of the injury, and then in simple and intelligent language told me that in all probability, if the wound healed as it should, the Duke would be a prisoner to his room for two or three weeks; if it healed badly, it might be as many months. But he put his estimate at not more than a month.

“There is no danger of his death?” I asked.

“Not the least, unless he is imprudent. In a month’s time he should be quite able to fight another duel should he feel so disposed.”

I saw no wit in so grim a pleasantry, for he intended it as such, and turned away with a hasty word of thanks for his attention.

“Where to?” asked Zoiloff when we were mounted.

“Back to Sofia,” I answered promptly. “I am going straight to General Kolfort to ascertain the meaning of last night’s attempt on me;” and I clapped my heels into my horse’s flanks and started at a sharp pace for the city.