CHAPTER XXIX

GENERAL KOLFORT TO THE RESCUE

AS I stood in a last second of desperate thought I heard the crash of glass, and I knew the men were breaking into the house; and I knew, too, that another minute would see them in the room where I should be caught red-handed. The instant General Kolfort returned to consciousness he would be the first to denounce me, despite the fact that I had saved him from death. He would only too gladly use against me the awful proofs of my apparent guilt which the mad woman had afforded by her self-murder. It was just such a chance as he would welcome.

I dared not leave him behind me.

I seized him, and, tearing with the strength of passion at his bonds, tugged and wrenched until I freed his hands and lifted him in my arms. He was still faint, though I detected now the signs of returning consciousness. Then I extinguished the light, darted with him through the entrance into the secret passage, and, clapping a hand over his mouth that he should utter no sound when his senses came back, I drew my revolver, and peering through the glass into the dark room, stood at bay, resolved to sell my life dearly, whatever chanced.

But I had secured a magnificent hostage for ultimate freedom, could I only get through this mess. It would all turn on what happened when the General’s men entered the room, and I clenched my teeth as I stared into the darkness.

There was no long wait. I had barely hidden myself when someone knocked at the door of the room, paused for a reply, knocked again, and entered. Two men came in, the faint light from the hall beyond showing up their uniformed figures.

“This isn’t the room; it’s all in darkness,” said one in a deep bass voice.

“Yes, it is; it’s the library,” said the other, who evidently knew the house. “Are you there, General? Did you call?”

They both waited for an answer, and, getting none, came further into the room.

“It can’t be it,” said the first speaker.

“Better get a light,” returned the second. “I know it is the right room.”

“Well, it’s devilish odd.” Fumbling in his pocket, he got a match, struck it and held it up, glancing round the room with the faint, flickering light held above his head.

“Here’s a lamp,” said his companion; “hot too, only just put out. I don’t like this. Where can the General be?”

“Better mind what we’re doing, Loixoff. The General won’t thank us to come shoving our noses into his affairs.”

“You heard the scream for help, Captain?”

“Yes, but it wasn’t the General’s voice,” returned the Captain drily. “And he was alone with the woman we were to take prisoner afterwards.”

They were lighting the lamp when this little unintentional revelation of old Kolfort’s intended treachery to the Countess Bokara was made.

At that moment I felt my prisoner move, and I pressed my hand tightly over his mouth and held him in a grip that made my muscles like steel, lest he should struggle, and, by the noise, bring the men upon us.

When they had lighted the lamp they stood looking round them in hesitation. From where they stood the body of the dead woman was concealed by the table.

“The General’s been here,” said the man who had been addressed as Loixoff. “Here are his cap and gloves.” They lay not far from the lamp. “What had we better do?”

My prisoner made another movement then and drew a deep breath through his nostrils, and I felt his arm begin to writhe in my grip. I slipped my revolver into my belt for a moment, lifted him up in my arms, holding him like a child, put his legs between mine while I pinioned him with my left arm so that he could not move hand or foot, and moved my right hand up to cover both nostrils and mouth. I would stifle his life out of him where he lay rather than let him betray me.

I could understand the men’s hesitation. Old Kolfort was certain to resent any interference or prying on their part into his secrets, and they foresaw that the consequences to them might be serious if they were to do what he did not wish. He knew how to punish interlopers. They were afraid, and I began to hope that, after all, I should yet get out of this plight if I could only keep my prisoner quiet.

Even if I had to kill him I could still get the paper I had come for; and as no one would know of my visit to the house, no glint of suspicion would ever fall on me. At this thought I almost hoped he would die.

The two men stood in sore perplexity for a time that seemed an hour to me, but may have been a couple of minutes, and then the elder one, the Captain, said:

“We’d better look through the other rooms.”

“As you please,” said his companion, and he turned away while the Captain picked up the lamp.

“I can’t understand it,” he muttered.

“Perhaps we’d better not try,” said Loixoff. As he spoke he started, and I saw him stare at the spot where the Countess lay. “By God! Captain, there’s the woman, dead!”

They crossed the room together, and while the Captain held the lamp down close to the body Loixoff examined it.

“It’s that fiend, Anna Bokara,” he cried. “Now we know what that scream meant.”

“Is she dead?”

“Yes; here’s a knife thrust right through her heart. There’s no pulse,” he added after a pause. “Is this his work?”

“It must be,” returned the Captain; and I saw them look meaningly into each other’s eyes.

“We’d best clear out of this,” said the Captain. “I suppose it’s only a case of suicide after all,” he added significantly.

“Probably,” was Loixoff’s dry answer as he rose from his knees. “Where’s the General, do you think?”

“I never think in these cases;” and the Captain put the lamp down, taking care to find the exact spot where it had stood, and then extinguished it. “We’ll wait till he calls us, Loixoff. And mind, not a word that we’ve been here. Leave the General to make his own plans.”

They went out, closing the door softly behind them, and I heard them leave the house. As I pushed open the doors of the cabinet again their steps crunched on the gravel outside as they walked away down the drive.

I breathed freely once more. I was safe so far, and in the relief from the strain of the last few terrible minutes my muscles relaxed, and I leant against the wall with scarcely sufficient strength to prevent my companion from slipping out of my arms to the floor.

But there was still much to be done, and I made a vigorous effort to pull myself together. I relit the lamp, but placed it so that no gleam of the light could be seen through the windows. Then laying my prisoner, who had fainted again as the result of my rough treatment of him in the hiding-place, on a couch, I secured the paper of the route I was to take to the frontier.

Next I applied myself vigorously to restore him to consciousness. I dashed cold water in his face, and then, getting brandy from a cupboard in the room, I poured some down his throat, and bathed his forehead. The effect was soon apparent; his breathing became deeper and more regular, until with a deep-drawn sigh he opened his eyes and stared at me, at first in a maze of bewilderment, but gradually with gathering remembrance and recognition.

“You’ll do now, General; but you’ve had a near shave. If I hadn’t come in the nick of time that woman’s knife would have been in your heart,” I said.

He started, and terror dilated his pupils as he glanced wildly about him.

“You’re safe from her. She’s killed herself. Drink this;” and I gave him more brandy. As I handed it to him he started again and stared at the blood on my hand. He was still scared enough for my purposes. He drank the brandy and it strengthened him, and presently he struggled and sat up.

I drew out my revolver, made a show of examining it to make sure that it was loaded, and put it back in my pocket. I had run my hands over him before to make certain that he had no weapon.

“What are you going to do?” he asked, with a glance of fresh terror.

“Not to use that unless you force me,” I said, with a look which he could read easily enough. “As soon as you’re ready to listen I’ve something to say.”

He hid his face behind his trembling hands in such a condition of fright that I could have pitied him had it not been necessary for me to play on his fears. He sat like this in dead silence for some minutes, and I waited, thinking swiftly how to carry out the plan I had formed.

“What is it you want?” he asked at length.

“You came here to-night to meet the Countess Bokara in the belief that she could put into your hands such papers as would give you an excuse to have me put to death, and when she had done it you meant to have had her arrested. Instead of that you fell into her trap, and she was on the point of killing you when I interfered and saved your life. Then she turned on me and struggled to kill me in order that she might carry out her purpose. Her failure drove her insane, and in her frenzy of baulked revenge she plunged the knife into her own heart. You will therefore write out a statement of these facts while they are still fresh in your mind, sign it, and give it to me.”

I pointed to my table, on which I had laid the writing materials in readiness. He was fast recovering his wits, if not his courage, and he listened intently as I spoke. I saw a look of cunning pass over his face as he agreed to what I said, and crossed to the writing-table. He thought he could easily disown the statement, and had been quick to perceive the use he could make of the facts against me. But he did not know the further plan I had, and he wrote out a clear statement exactly as I had required.

“Seal it with your private seal,” I said when he had signed it, his handwriting throughout having been purposely shaky. He would have demurred, but I soon convinced him I was in no mood to be fooled with. “Your seal can’t be disowned as a forgery,” I said pointedly. “And now, as your hand has recovered its steadiness, you can write this again—this time, if you please, so that no one can mistake it;” and while he did this I watched him closely to prevent a similar trick.

“Good!” I exclaimed when all was finished. The second paper he had written I folded up carefully and placed in my pocket; the first I laid inside the dress of the dead woman, in such a position that anyone finding the body must see the paper.

“That will explain what has happened when the body is found,” I said drily. “I want the facts made very plain.” He looked at me with an expression of hate and fear and cunning combined.

“I must go; I am not well,” he said.

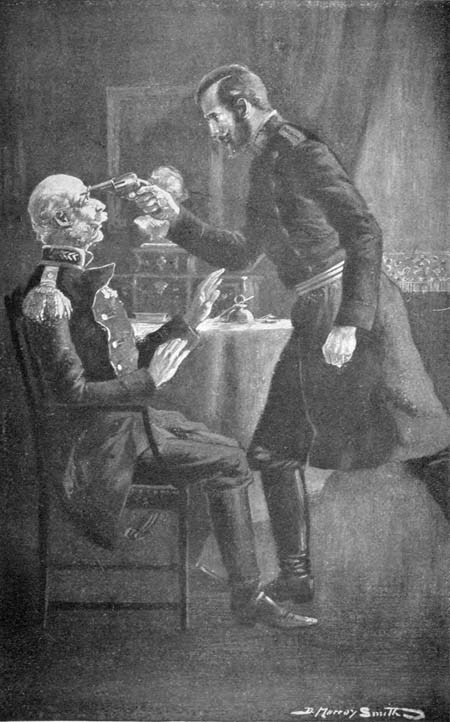

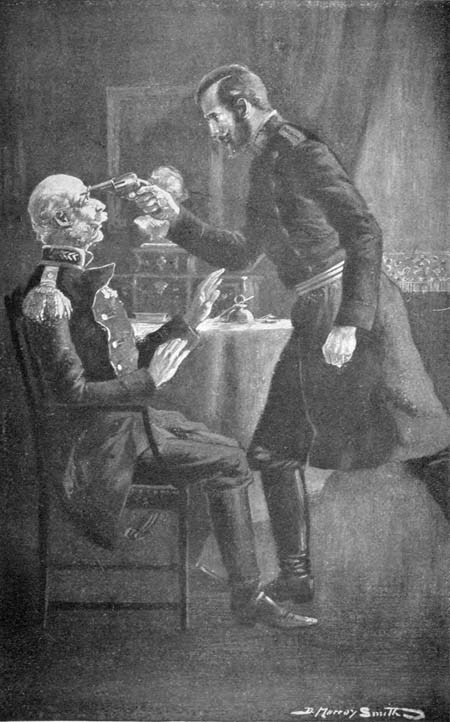

“We are going together, General,” I returned quietly. “I am willing to assume that you are so grateful to me for having saved your life, that in turn you wish to secure my safety. You have had me arrested once, your men have treated me like a felon, you have filled the roads with your agents until I cannot take a step without further fear of instant capture, and up to this moment you have sought my life with tireless energy; but now you are so concerned for my safety, so eager to repair your mistaken estimate of me, and heedful for my welfare, that you are going to see me safe to the Servian frontier. That is the part you are cast for; and, listen to me, if you refuse, if you give so much as a sign or suggestion of treachery, if you don’t play that part to the letter, I swear by all I hold sacred I’ll scatter your brains with this pistol;” and I clapped it to his head till the cold steel pressed a ring on his temple. “Now what do you say?”

He cowered and shrank at my desperate words, and all the horror and fright of death with which the Countess Bokara had filled his soul came back upon him again as he stared helplessly up at me. His dry bloodless lips moved, but no sound passed them; he lifted his hands as if in entreaty, only to drop them again in feeble nervelessness; and he shook and trembled like one stricken with sudden ague.

“You value your life, I see, and you can earn it in the way I’ve said. So long as I am safe you will be safe, and not one second longer. That I swear. If there is danger on the road for me it is your making, and you shall taste of the risks you order so glibly for others. Every hazard that waits there for me will be one for you as well. You are dealing with a man you have rendered utterly reckless and desperate. Remember that. Now, do you agree?”

“Anything,” he whispered, in so low a tone that I could only catch it with difficulty.

“THE COLD STEEL PRESSED A RING ON HIS TEMPLE.”—

“Then we’ll make a start. Come first with me.” I led him upstairs to my dressing-room, and made him wait while I exchanged the uniform I was wearing for a civilian’s dress, and shaved off my beard and moustache. He sat watching me in dead silence, his eyes following my every action, much like a man spellbound and fascinated. I had saturated him through and through with fear of me, till his very brain was dizzy and dimmed with terror.

When my hasty preparations were finished, I took him down to the shooting gallery while I armed myself with a stout sword-stick of the highest temper, testing the blade before him, and took a plentiful supply of ammunition for my revolver. I kept absolute silence the whole time, letting the looks which I now and again cast on him tell their own story of my implacable resolve. He was like a weak woman in his dread of me, and at every fierce glance of mine he started with a fresh access of terror.

When all was ready for my start, I drew the plan of my route from my pocket and studied it carefully.

“I am ready,” I said; “and now mark me. You will call up one of your men. What is that Captain’s name who is here with you?”

“Berschoff,” he answered, like a child saying a lesson.

“You will call up Captain Berschoff and order him to draw off his men, and to send your carriage, unattended, mind, up to the front door. You will be careful that the Captain does not see me. When the carriage comes, you will order your coachman to drive you as fast as he can travel to the village of Kutscherf. While you are speaking to Captain Berschoff my hand will be on your shoulder and my revolver at your head, and if you dare to falter in so much as a word or syllable of what I have told you, that moment will be your last on earth. Come!”

I held my revolver in hand as we left the gallery and went to the door of the house.

My breath came quickly in my fast-growing excitement, for I knew that a moment would bring the crisis on the issue of which all would turn. When once I had got rid of his men, his sense of helplessness would be complete, and my task would be lighter. But my fear was that in his cunning he might even dare to play me false in the belief that I should be afraid to make my threat good. He knew as well as I that to shoot him right in front of his captain would be an act fraught with consummate peril for me.

My heart beat fast as I unfastened the heavy door, opened it, and turning gripped him by the shoulder as he went forward on to the step and called to Captain Berschoff.

Then I pulled him back, closed the door to within a couple of inches, and, planting my foot to prevent it being opened wider, I pressed the barrel of the pistol to his head, as we stood listening to the hurried footsteps of the approaching officer.