CHAPTER XXXII

A HUNDRED LASHES

I WAS not without apprehension that, as soon as the drunkards and rowdies woke up, there would be some renewal of the night’s disturbances, with trouble to follow for the women and for us who had kept watch over them.

But the anticipation was unfounded. The men were too ill to make trouble. The fearful atmosphere they had breathed, combined with the effects of their intoxication, had sapped alike their strength and their energy. Listless, sick both in mind and body, crushed in spirit and utterly downcast, they kept apart from us and huddled together in a compact companionship of weary, lifeless, dejected wretchedness.

Several of those at our end of the prison, men and women alike, were in much the same condition. Daylight appeared to add to their sufferings, instead of diminishing it. In the dim gas light they had been spared the sight of the other’s condition; but it was revealed to them now and made them the more conscious of their own evil plight. The pestilential atmosphere had also enfeebled them; and the frail little Pia and her strong helpmate were hard put to it to keep them from giving way. Many of them fainted, gasping piteously for air; and Pia asked me to get the men to help in holding one or two of them up to the windows that they might breathe fresh air in place of the pestilence-laden atmosphere of the gaol.

The men agreed readily, although themselves greatly weakened by the night’s experiences, and I had just laid down one woman whom a companion had helped me to revive in this way, when he began to speak of Pia; praising her courage, her endurance and her resource.

“She is a little heroine and will be missed by our friends,” he said, when I echoed his praises warmly. “I hope they can prove nothing against her. How long have you known her?”

“I saw her for the first time here.”

“She is heart and soul in our cause and one of the staunchest workers and the bravest.”

“What cause is yours, my friend?”

“You are right to be cautious; but my cause is yours, and yours mine.”

At this moment Pia touched me on the arm. “Will you come and look at this poor soul here?” she asked; and as I turned and we bent over a woman who had fainted, she whispered hurriedly: “That man is a spy. Be careful what you say to him.”

I was astounded. It seemed incredible that any money, any reward however lavish, could induce a man to face the horrors of such an inferno as that gaol.

“Can you lift her to the window?” asked Pia, seeing my look of incredulity; and she whispered: “It is true. I know. Be very careful.”

The man helped me hold the unconscious woman to the air; and when we set her down somewhat revived, he was at me again, seeking to draw some compromising admissions from me in response to his own violent abuse of the Government.

“You are mistaken about me and should not speak so unguardedly to a stranger even in this place,” I answered.

“I should not had I not seen how you sympathize with our friends here. It is true we have not met before, and in that sense we are strangers; but a fellowship of suffering in our common cause makes us all friends—aye, and more than friends.”

“What I have done has been done for motives of mere humanity.”

“But they recognize a leader in you—and I proclaim myself as devoted a follower as any of them.”

“I am no leader of any cause, man. I am an Englishman; my name is Donnington; and I have been brought here through the blundering of the police.”

“They are devils,” he exclaimed vehemently, and then tried to lead me into joining in his abuse of them. But little Pia had put me on my guard, and after a time he abandoned his efforts and fastened on to another man, with results I was delighted to see.

The man listened for a while and presently, taking offence at something which the spy said, answered hotly; the spy lost his temper and let fall a remark which others beside the man he was pumping resented. They closed round him and first thrashed him soundly and then knocked him across to the other group. The latter glad to get hold of one of us grabbed hold of him, and venting on his cowardly body all the rage they dared not vent on us, they beat and kicked and mauled him unmercifully, until his screams for help attracted the attention of the warders and they entered and dragged him away.

Knowing that he would seek revenge by lying about us, I got from Pia all the names of the men who had stood by me during the night, so that when I was out of my own troubles, I might tell Volheno what had really occurred.

Soon after that the door was thrown open and several officials entered. They made a careful note of the unusual division of the prisoners into the two groups, and at once ordered the removal of those with whom we had had the trouble.

While this was going on I went up to the chief official and told him my name and asked for food for myself and those remaining. I was famished and parched with thirst. I had not had even a crust of bread for twenty-four hours and only the sip of brandy which Inez had given me.

His reply was an oath and an order to hold my tongue.

I pointed to the women and asked for food for them, and the brute raised his hand and struck me across the mouth.

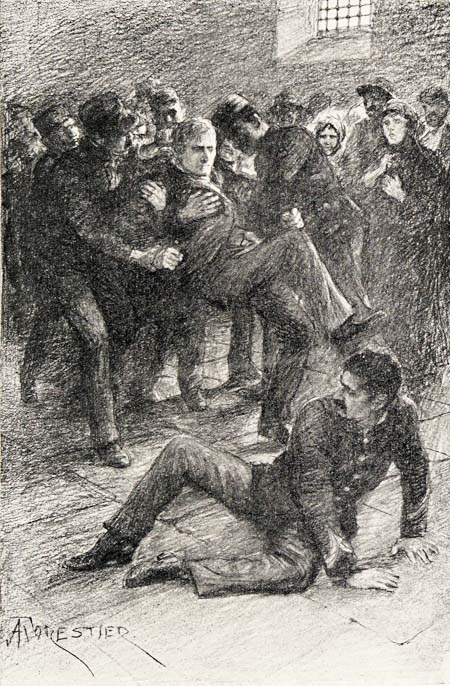

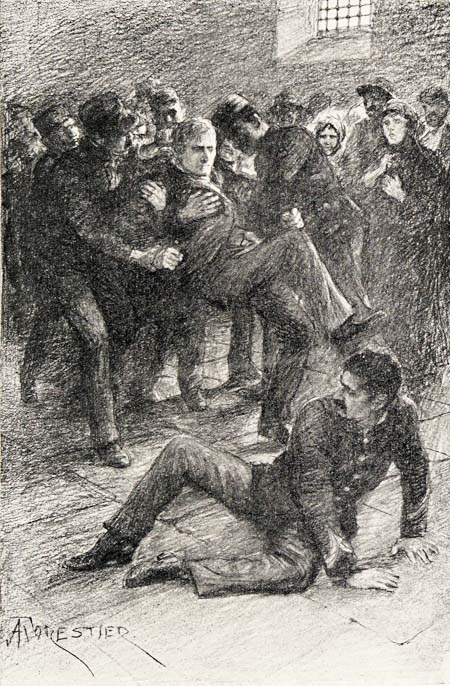

Mad with rage at this, I sprang on him and pulled him down, dashing his head against the stone flags. In a moment half a dozen of his men rushed up and dragged me off, kicking and mauling me with the utmost violence, and then put my wrists in irons.

Their leader rose livid with rage. “You shall have the lash for this, you traitorous dog,” he hissed between his teeth. “Fling him in the corner there,” he ordered. “The lash shall tear the flesh from your back for this. Yes, the lash and plenty of it. That shall be your breakfast. Yes, the lash, the lash;” and he repeated this several times, each time with a fierce and bitter oath, as if gloating in the prospective treat of seeing my flesh cut to ribbons.

I was flung into the corner, as he had ordered—the loathsome spot, reeking with all the filthy abominations of the vile crew who had passed the night in it—and the other prisoners were forbidden to come near me under penalty of sharing my punishment. But the door had scarcely closed on them before little Pia came straight across, with gentle reproaches for my futile violence and words of sympathy for my trouble.

I tried to send her away, fearing the warders would return and find she had disobeyed their order; but she would not go. The skin of my face was broken slightly where one of the men had kicked me—only a graze, for the force of the kick was spent before his foot touched me; and she insisted upon wiping the few drops of blood away. Her touch was that of a hand skilled in healing; and as she did what she could to cleanse the little wound, her eyes were full of tears and her face a living mask of pity and sympathy.

“In a moment half a dozen of his men rushed up

and dragged me off.”

“Go, go before they return and find you here,” I urged her.

“Is it not you who saved us all from the worst terrors of this awful night? Shall I desert you now you have brought this trouble on yourself?”

“Go, please go. You can do me no good and only harm yourself,” I begged her; but she would not go, and was still with me when the men came back to lead me out.

They seized her at once and, being brutes not men, handled her with cruel violence. I would have cursed them in my empty rage had it not seemed like a dishonour to her, in her calm quiet, almost saint-like resignation.

We were taken out together into a large quadrangle, and I caught my breath with a shiver of panic as I saw on the other side the whipping post surrounded by a group of men, two of whom held many-thonged, heavily knotted whips.

We were led across to it and a halt was made, and the two powerful men with the whips eyed us both with sinister, half-gloating gaze.

I was ashamed of my cowardice then. Grit my teeth as I would in a firm resolve to bear the awful punishment of the lash, I turned cold and sick at the thought of it. But the frail creature by my side was utterly unmoved. She was pale, but no paler than usual, and as calm and unmoved as the whipping post itself.

To the brutalized ruffians, the tragedy was more like a pleasant farce.

“Only two this morning?” asked one of those holding a whip.

“May be more presently,” replied one of the men with us.

“I want more exercise than this,” was the growling answer, uttered with a sort of snarling laugh.

“You’ll have plenty with this dog. He struck the captain.”

“He looks as if he had less stomach for his breakfast than the girl here.”

The taunt bit like an acid and did more than anything could have done to revive my drooped courage.

In this coarse way they jested until another prisoner was brought out from a different cell and tied up for the lash. I will not dwell on the sickening scene which followed. I shut my eyes and, had I not been ironed, would gladly have closed my ears as well to keep out the awful sound of the poor wretch’s screams, until the blessed relief of unconsciousness silenced them.

Pia stood with her hands clasped to her eyes and her thumbs pressed close to her ears, and did not look up until the unfortunate victim was carried away, the blood dripping from his lacerated back making a gruesome and significant track across the flags.

I thought my flogging would follow immediately; but it turned out otherwise. We had merely been made to witness the terrible punishment that our courage might be broken and our senses racked by the sight of what was in store for us.

Instead of being triced up to the post, we were led away into another part of the building; and one of the men with me explained with a chuckle that such a number of strokes as I should receive for my offence could only be ordered by the Governor of the prison himself.

As we were taken into the room I saw the officer I had struck, who was addressed as Captain Moros, in close consultation with a tall, thin, grey-bearded man in an elaborate uniform decorated with several medals. This was His Excellency the Governor. He frowned at me over the rims of his pince-nez; and I perceived at once that he had been already informed of my heinous deed, and that the captain had made the case as black as possible.

“This is the man, I suppose?” the Governor asked him.

“Yes,” said the captain, and he turned to the warders by my side.

“Is he securely ironed? He is a very desperate and very dangerous ruffian,” he added to the Governor. “I have ascertained that he nearly killed one of his fellow-prisoners in the night and instigated an attack upon another of them this morning;” and he bent toward the Governor and whispered to him.

He was describing the incident of the spy’s mauling, and he finished in a tone loud enough to reach me. “There is no doubt he recognized him and was at the bottom of the whole thing.”

“Who is he? Is he known to our men?”

“Oh, yes. I have made inquiries. He is one of the most violent revolutionaries in the city. Altogether a most reckless, dangerous man. I am able to vouch for all this personally; and there is no doubt he meant to kill me. I had a most marvellous escape.”

“How do you say the attack was made?”

“Without a word of warning. I was watching as some of the prisoners were taken out of the cell and he sprang on me suddenly from behind and tried to throttle me. It took half a dozen men to drag him away.”

“Certainly a very bad case; as bad as it could be. And the woman, who is she?” asked the Governor.

“A political suspect in league with the man. I have reason to believe that she incited him to attack me. I had the fellow separated from the rest and ordered them not to go near him on pain of sharing his punishment. I really did that as a test to find out if he had any close associates among them. She went to him at once in defiance of my orders; and I find that they are old companions. They acted together all the night in a very suspicious manner indeed.”

“She looks very young and fragile for such a punishment.”

“Your Excellency will see that flagrant disobedience of our orders such as this woman was guilty of cannot be passed over. She knew the penalty of disobedience; and if prisoners find that we can be set at defiance with impunity, the difficulty of keeping them in subjection will be very great. I feel that my sense of duty compels me to press this case.”

“I see that, of course. The doctor had better examine her to see if she can bear the punishment.”

“You may of course leave that to me,” was the reply; and the Governor was quite willing to do it.

A pause followed, and I was waiting to be questioned, for I had not even been asked my name, when Pia’s clear young voice broke the silence.

“General de Sama.”

If a bomb had exploded suddenly in the room it would not have produced much more astonishment. The Governor looked up with surprise; the captain shouted “Silence her;” and the two men holding Pia shook her angrily, one of them clapping a hand to her mouth. It was evident that none but official dogs must bark in that place, and for a prisoner to open her lips was a crime.

I made an effort to explain, but before a couple of words were out of my lips, I was silenced as Pia had been.

When the commotion caused by this had subsided, the Governor addressed me. “You have attempted the life of Captain Moros and you are evidently a very dangerous and desperate man. The punishment for your crime under the law is death; but your intended victim has interceded for you and has mercifully asked that the case shall be dealt with, not as a capital crime against the law of the land, but as an offence against the discipline of the prison. As such I have power to deal with it. It is a very grave offence, very grave indeed, and the punishment must be in proportion to its gravity. You will receive a hundred lashes to be administered twenty strokes at a time with such intervals between each flogging as the doctor shall decide. You have every reason to be grateful to Captain Moros for his leniency. As for you,” he added, turning to Pia, “your case is different, but I am compelled to uphold the discipline of the prison. You knew beforehand the punishment of disobedience. But you are young and may have been led into this trouble by your evil companion there. You will receive five strokes with the lash.”

With that he signed to the men to take us away.

I was so dazed, stunned and overwhelmed by the terrible sentence that even the gloating look of triumph and malice on Captain Moros’ face failed to rouse my resentment, as my guards hustled me away.