CHAPTER II

DEVELOPMENTS

MY view of the trouble was that it was a case of robbery. The disordered condition of the city was sure to be used by the roughs as a cover for their operations; and I jumped to the conclusion that the woman whose cry I was answering had been decoyed to the house to be robbed.

But as I ran down the stairs I heard enough to show me that it was in reality a sort of by-product of the riot in the streets. The woman was a prisoner in the hands of some of the mob, and they were threatening her with violence because she was, in their jargon, an enemy of the cause of the people.

To my surprise it was against this that she was protesting so vehemently. Her speech, in strong contrast to that of the men, was proof of refinement and culture, while the little note of authority which I had observed at first suggested rank. It was almost inconceivable, therefore, that she could have anything in common with such fellows as her captors.

The door of the room in which they all were stood slightly ajar, and as I reached it she reiterated her protest with passionate vehemence.

“You are mad. I am your friend, not your enemy. I swear that. One of you must know Dr. Barosa. Find him and bring him here and he will bear out every word I have said.”

“Holding my revolver in readiness, I entered.”

“That’s enough of that. Lies won’t help you,” came the reply in the same gruff bullying tone I had heard before. “Now, Henriques,” he added, as if ordering a comrade to finish the grim work.

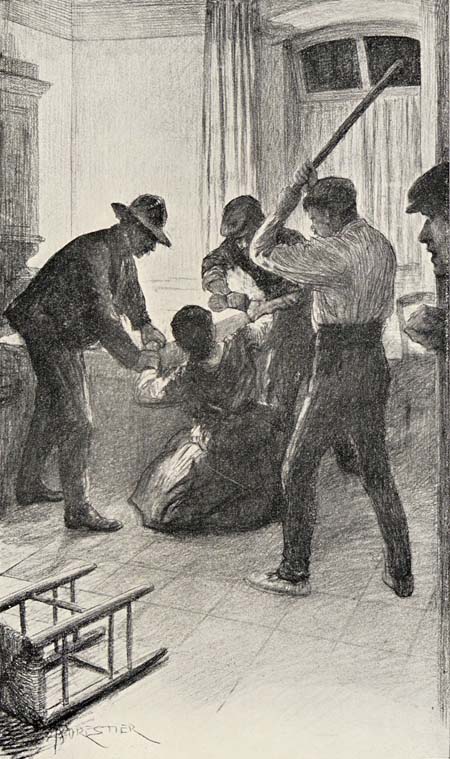

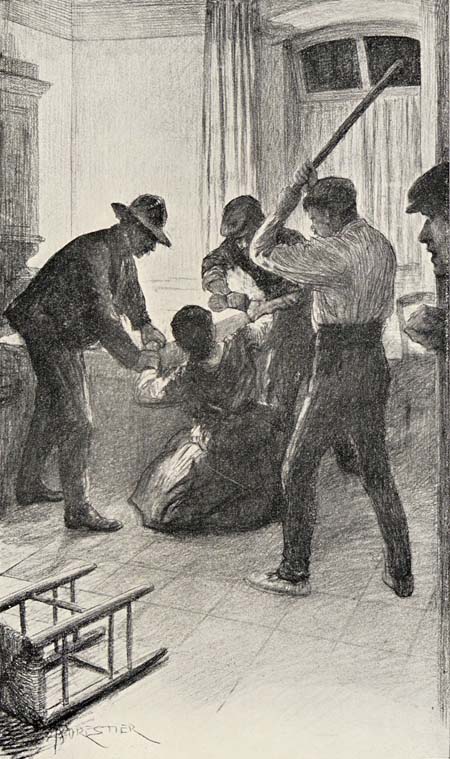

Holding my revolver in readiness, I entered. There were three of the rascals. Two had hold of the woman who knelt between them with her back to me, while the third, also with his back to me, was just raising a club to strike her.

They were so intent upon their job and probably so certain that no one was in the house, that they did not notice me until I had had time to give the fellow with the club a blow on the side of the head which sent him staggering into a corner with an oath of surprise and rage. The others released their hold of the woman, and as I stepped in front of her, they fell away in healthy fear of my levelled weapon.

They were the reverse of formidable antagonists; rascals from the gutter apparently; venomous enough in looks, but undersized, feeble specimens; ready to attack an unarmed man or a defenceless woman, but utterly cowed by the sight of the business end of my revolver.

They slunk back toward the door, rage, baulked malice and fear on their ugly dirty faces.

“A spy! A spy!” exclaimed the brute who had the stick; and at the word they felt for their knives.

“Put your hands up, you dogs,” I cried. “The man who draws a knife will get a bullet in his head.”

Meanwhile the woman had scrambled to her feet, with a murmured word of thanks to the Virgin for my opportune intervention, and then to my intense surprise she put her hand on my arm and said in a tone of entreaty: “Do not fire, monsieur. They have only acted in ignorance.”

“You hear that, you cowardly brutes,” I said, without turning to look at her, for I couldn’t take my eyes off the men. “Clear out, or——” and I stepped toward them as if I meant to fire.

In that I made a stupid blunder as it turned out. They hung together a second and then at a whisper from the fellow who appeared to be the leader, they suddenly bolted out of the room, and locked the door behind them.

Not at all relishing the idea of being made a prisoner in this way, I shouted to them to unlock the door, threatening to break it down and shoot them on sight if they refused. As they did not answer I picked up a heavy chair to smash in one of the panels, when my companion again interposed.

But this time it was on my and her own account. “They have firearms in the house, monsieur. If you show yourself, they will shoot you; and I shall be again at their mercy.”

She spoke in a tone of genuine concern and, as I recognized the wisdom of the caution, I put the chair down again and turned to her.

It was the first good square look I had had at her, and I was surprised to find that she was both young and surpassingly handsome—an aristocrat to her finger tips, although plainly dressed like one of the people. Her features were finely chiselled, she had an air of unmistakable refinement, she carried herself with the dignity of a person of rank, and her eyes, large and of a singular greenish brown hue, were bent upon me with the expression of one accustomed to expect ready compliance with her wishes. She had entirely recovered her self-possession and in some way had braided up the mass of golden auburn hair, the dishevelled condition of which I had noticed in the moment of my entrance.

“You are probably right, madame,” I said; “but I don’t care for the idea of being locked in here while those rascals fetch some companions.”

I addressed her as madame; but she couldn’t be more than four or five and twenty, and might be much younger.

“There will be no danger, monsieur,” she replied in a tone of complete confidence.

“There appeared to be plenty of it just now; and the sooner we are out of this place, the better I shall be pleased.” And with that I turned to the window to see if we could get out that way. It was, however, closely barred.

“You may accept my assurance. These men have been acting under a complete misunderstanding. They will bring some one who will explain everything to them.”

“Dr. Barosa, you mean?”

“What do you know of him?” The question came sharply and with a touch of suspicion, as it seemed to me.

“Nothing, except that I heard you mention him just as I entered.”

She paused a moment, keeping her eyes on my face, and then, with a little shrug, she turned away. “I will see if my ser—my companion is much hurt,” she said, and bent over the man who was lying against the wall.

I noticed the slip; but it was nothing to me if she wished to make me think he was a companion instead of a servant.

She knew little or nothing about how to examine the man’s hurt, so I offered to do it for her. “Will you allow me to examine him, madame? I have been a soldier and know a little about first aid.”

She made way for me and went to the other end of the room while I looked him over. He had had just such a crack on the head as I feared for myself when bolting from the troops. It had knocked the senses out of him; but that was all. He was in no danger; so I made him as comfortable as I could and told her my opinion.

“He will be all right, no doubt,” was her reply, with about as much feeling as I should have shown for somebody else’s dog; and despite her handsome face and air of position, I began to doubt whether he would not have been better worth saving than she.

“How did all this happen?”

She gave a little impatient start at the question, as if resenting it. “He was brought here with me, monsieur, and the men struck him,” she replied after a pause.

“Yes. But why were you brought here?”

“I have not yet thanked you for coming to my assistance, monsieur,” she replied irrelevantly. “Believe me, I do thank you most earnestly. I owe you my life, perhaps.”

It was an easy guess that she found the question distasteful and had parried it intentionally; so I followed the fresh lead. “I did no more than I hope any other man would have done, madame,” I said.

“That is the sort of reply I should look for from an Englishman, monsieur.” Her strange eyes were fixed shrewdly upon me as she made this guess at my nationality.

“I am English,” I replied with a smile.

“I am glad. I would rather be under an obligation to an Englishman than to any one except a countryman of my own.” She smiled very graciously, almost coquettishly, as if anxious to convince me of her absolute sincerity. But she spoilt the effect directly. Lifting her eyes to heaven and with a little toss of the hands, she exclaimed. “What a mercy of the Virgin that you chanced to be in the house—this house of all others in the city.”

I understood. She wished to cross-examine me. “You are glad that I arrived in time to interrupt things just now?” I asked quietly.

“Monsieur!” Eyes, hands, lithe body, everything backed up the tone of surprise that I should question it. “Do I not owe you my life?” I came to the conclusion that she was as false as woman of her colour can be. But she was an excellent actress.

“Then let me suggest that we speak quite frankly. Let me lead the way. I am an Englishman, here in Lisbon on some important business, and not, as the doubt underneath your question, implies—a spy. I——”

“Monsieur!” she cried again as if in almost horrified protest.

“I was caught in the thick of a street fight,” I continued, observing that for all her energetic protest she was weighing my explanation very closely. “And had to run for it with the police at my heels. I saw a window of this house standing partly open and scrambled through it for shelter.”

“What a blessed coincidence for me!”

“It would be simpler to say, madame, that you do not believe me,” I said bluntly.

“Ah, but on my faith——”

“Let me put it to you another way,” I cut in. “I don’t know much of the ways of spies, but if I were one I should have contented myself with listening at that door, instead of entering, and have locked you all in instead of letting myself be caught in this silly fashion.” Then I saw the absurdity of losing my temper and burst out laughing.

She drew herself up. “You are amused, monsieur.”

“One may as well laugh while one can. If my laugh offends you, I beg your pardon for it, but I am laughing at my own conversion. An hour or two back I was ridiculing the idea of there being anything to bother about in the condition of the Lisbon streets. Since then I have been attacked by the police, nearly torn to pieces by the mob, had to bolt from the troops, and now you thank me for having saved your life and in the same breath take me for a spy. Don’t you think that is enough cause for laughter? If you have any sense of humour you surely will.”

“I did not take you for a spy, monsieur,” she replied untruthfully. “But you have learnt things while here. We are obliged to be cautious.”

“My good lady, how on earth can it matter? We have met by the merest accident; there is not the slightest probability that we shall ever meet again; and if we did—well, you suggested just now that you know something of the ways of us English, and in that case you will feel perfectly certain that anything I have seen or heard here to-night will never pass my lips.”

“You have not mentioned your name, monsieur?”

“Ralph Donnington. I arrived yesterday and stayed at the Avenida. Would you like some confirmation? My card case is here, and this cigar case has my initials outside and my full name inside.”

“I do not need anything of that sort,” she cried quickly, waving her hands. But she read both the name and the initials.

“What have you inferred from what you have seen here to-night?”

“That the rascals who brought you here are some of the same sort of riff-raff I saw attacking the police and got hold of you as an enemy of the people. I heard that bit of cant from one of them. That you are of the class they are accustomed to regard as their oppressors was probably as evident to them as to me; and when you expressed sympathy with them——”

“You heard that?” she broke in earnestly.

“Certainly, when I heard you tell them to fetch this Dr. Barosa. But it is nothing to me; nor, thank Heaven, are your Portuguese politics or plots. But what is a good deal to me is how we are going to get out of this.”

“And for what do you take me, monsieur?”

“For one of the most beautiful enthusiasts I ever had the pleasure of meeting, madame,” I replied with a bow. “And a leader whom any one should be glad indeed to follow.”

She was woman enough to relish the compliment and she smiled. “You think I am a leader of these people, then?”

“It is my regret that I am not one of them.”

“I am afraid that is not true, Mr. Donnington.”

“At any rate I shall be delighted to follow your lead out of this house.”

“You will not be in any danger, I assure you of that.”

As she spoke we heard the sounds of some little commotion outside the room and I guessed that the scoundrels had brought up some more of their kind.

“I hope so, but I think we shall soon know.”

“I have your word of honour that you will not breathe a word of anything you have witnessed here to-night.”

“Certainly. I pledge my word of honour.”

The men outside appeared to have a good deal to chatter about and seemed none too ready to enter. They were probably discussing who should have the privilege of being the first to face my revolver. I did not like the look of the thing at all.

“If they are your friends, why don’t they come in?” I asked my companion. “Hadn’t you better speak to them?”

She crossed to the door and it occurred to me to place the head of a chair under the handle and make it a little more difficult for them to get in.

“You need have no fear, Mr. Donnington,” she said with a touch of contempt as I took this precaution.

“It’s only a slight test of the mood they are in.”

As she reached the door the injured man began to show signs of recovering his senses; and I stooped over him while she spoke to the men.

“Is Dr. Barosa there?” she called.

Getting no reply, she repeated the question and knocked on the panel.

There was an answer this time, but not at all what she had expected. One of the fellows fired a pistol and the bullet pierced the thin panel and went dangerously near her head.

I pulled her across to a spot where she would be safe from a chance shot. Only just in time, for half a dozen shots were fired in quick succession.

She was going to speak again, but I stopped her with a gesture; and then extinguished one of the two candles by which the room was lighted.

A long pause followed the shots, as if the scoundrels were listening to learn the effect of the firing.

In the silence the man in the corner groaned, and I heard the key turned in the lock as some one tried to push the door open.

I drew out my weapon.

“You will not shoot them, Mr. Donnington?” exclaimed my companion under her breath.

“Doesn’t this man Barosa know your voice?” I whispered.

“Of course.”

“Then he isn’t there,” I said grimly.

I raised my voice and called loudly: “Don’t you dare to enter. I’ll shoot the first man that tries to.” Then to my companion: “You’d better crouch down in the corner here. There’ll be trouble the instant they are inside.”

But she had no lack of pluck and shook her head disdainfully. “You must not fire. If you shoot one of these men you will not be safe for an hour in the city.”

“I don’t appear to be particularly safe as it is,” I answered drily.

There was another pause; then a vigorous shove broke the chair I had placed to the door and half a dozen men rushed in.

As I raised my arm to fire, my companion caught it and stopped me.

For the space of a few seconds the scoundrels stared at us, their eyes gleaming in vicious malice and triumph. I read murder in them.

“Throw your weapon on the table there,” ordered one of them.

Then a thought occurred to me.

I made as if to obey; but, instead of doing anything of the sort, I extinguished the remaining candle, grabbed my companion’s arm, drew her to the opposite side of the room and, pushing her into a corner, stood in front of her.

And in the pitchy darkness we waited for the ruffians to make the first move in their attack.