CHAPTER V.

THE LEVINGERS VISIT ROSHAM.

Seldom did Henry Graves spend a more miserable night than on this occasion of his return to Rosham. He had expected to find his father’s affairs in evil case, but the reality was worse than anything that he had imagined. The family was absolutely ruined—thanks to his poor brother’s wickedness, for no other word was strong enough to describe his conduct—and now it seemed that the remedy suggested for this state of things was that he should marry the daughter of their principal creditor. That was why he had been forced to leave the Navy and dragged home from the other side of the world. Henry laughed as he thought of it, for the situation had a comical side. Both in stories and in real life it is common enough for the heroine of the piece to be driven into these dilemmas, in order to save the honour or credit of her family; but it is unusual to hear of such a choice being thrust upon a man, perhaps because, when they chance to meet with them, men keep these adventures to themselves.

Henry tried to recall the appearance of the young lady; and after a while a vision of her came back to him. He remembered a pale-faced, silent girl, with an elegant figure, large grey eyes, dark lashes, and absolutely flaxen hair, who sat in the corner of the room and watched everybody and everything almost without speaking, but who, through her silence, or perhaps on account of it, had given him a curious impression of intensity.

This was the woman whom his family expected him to marry, and, as his sister seemed to suggest, who, directly or indirectly, had intimated a willingness to marry him! Ellen said, indeed, that she was “half in love” with him, which was absurd. How could Miss Levinger be to any degree whatsoever in love with a person whom she knew so slightly? If there were truth in the tale at all, it seemed more probable that she was consumed by a strange desire to become Lady Graves at some future time; or perhaps her father was a victim to the desire and she a tool in his hands. Although personally he had met him little, Henry remembered some odds and ends of information about Mr. Levinger now, and as he lay unable to sleep he set himself to piece them together.

In substance this is what they amounted to: many years ago Mr. Levinger had appeared in the neighbourhood; he was then a man of about thirty, very handsome and courteous in his manners, and, it was rumoured, of good birth. It was said that he had been in the Army and seen much service; but whether this were true or no, obviously he did not lack experience of the world. He settled himself at Bradmouth, lodging in the house of one Johnson, a smack owner; and, being the best of company and an excellent sportsman, gradually, by the help of Sir Reginald Graves, who seemed to take an interest in him and employed him to manage the Rosham estates, he built up a business as a land agent, out of which he supported himself—for, to all appearance, he had no other means of subsistence.

One great gift Mr. Levinger possessed—that of attracting the notice and even the affection of women—and, in one way and another, this proved to be the foundation of his fortunes. At length, to the secret sorrow of sundry ladies of his acquaintance, he put a stop to his social advancement by contracting a glaring mésalliance, taking to wife a good-looking but homely girl, Emma Johnson, the only child of his landlord the smack owner. Thereupon local society, in which he had been popular so long as he remained single, shut its doors upon him, nor did the ladies with whom he had been in such favour so much as call upon Mrs. Levinger.

When old Johnson the smack owner died, a few months after the marriage, and it became known that he had left a sum variously reported at from fifty to a hundred thousand pounds behind him, every farthing of which his daughter and her husband inherited, society began to understand, however, that there had been method in Mr. Levinger’s madness.

Owing, in all probability, to the carelessness of the lawyer, the terms of Johnson’s will were somewhat peculiar. All the said Johnson’s property, real and personal, was strictly settled under this will upon his daughter Emma for life, then upon her husband, George Levinger, for life, with remainder “to the issue of the body of the said George Levinger lawfully begotten.”

The effect of such a will would be that, should Mrs. Levinger die childless, her husband’s children by a second marriage would inherit her father’s property, though, should she survive her husband, apparently she would enjoy a right of appointment of the fund, even though she had no children by him. As a matter of fact, however, these issues had not arisen, since Mrs. Levinger predeceased her husband, leaving one child, who was named Emma after her.

As for Mr. Levinger himself, his energy seemed to have evaporated with his, pecuniarily speaking, successful marriage. At any rate, so soon as his father-in-law died, abandoning the land agency business, he retired to a comfortable red brick house situated on the sea shore in a very lonely position some four miles south of Bradmouth, and known as Monk’s Lodge, which had come to him as part of his wife’s inheritance. Here he lived in complete retirement; for now that the county people had dropped him he seemed to have no friends. Nor did he try to make any, but was content to occupy himself in the management of a large farm, and in the more studious pursuits of reading and archæology.

The morrow was a Saturday. At breakfast Ellen remarked casually that Mr. and Miss Levinger were to arrive at the Hall about six o’clock, and were expected to stay over the Sunday.

“Indeed,” replied Henry, in a tone which did not suggest anxiety to enlarge upon the subject.

But Ellen, who had also taken a night for reflection, would not let him escape thus. “I hope that you mean to be civil to these people, Henry?” she said interrogatively.

“I trust that I am civil to everybody, Ellen.”

“Yes, no doubt,” she replied, in her quiet, persistent voice; “but you see there are ways and ways of being civil. I am not sure that you have quite realised the position.”

“Oh yes, I have thoroughly. I am expected to marry this lady, that is, if she is foolish enough to take me in payment of what my father owes to hers. But I tell you, Ellen, that I do not see my way to it at present.”

“Please don’t get angry, dear,” said Ellen more gently; “I dare say that such a notion is unpleasant enough, and in a way—well, degrading to a proud man. Of course no one can force you to marry her if you don’t wish to, and the whole business will probably fall through. All I beg is that you will cultivate the Levingers a little, and give the matter fair consideration. For my part I think that it would be much more degrading to allow our father to become bankrupt at his age than for you to marry a good and clever girl like Emma Levinger. However, of course I am only a woman, and have no ‘sense of honour’ or at least one that is not strong enough to send my family to the workhouse when by a little self-sacrifice I could keep them out of it.”

And with this sarcasm Ellen left the room before Henry could find words to reply to her.

That morning Henry walked with his mother to the church in order to inspect his brother’s grave a melancholy and dispiriting duty the more so, indeed, because his sense of justice would not allow him to acquit the dead man of conduct that, to his strict integrity, seemed culpable to the verge of dishonour. On their homeward way Lady Graves also began to talk about the Levingers.

“I suppose you have heard, Henry, that Mr. Levinger and his daughter are coming here this afternoon?”

“Yes, mother; Ellen told me.”

“Indeed. You will remember Miss Levinger, no doubt. She is a nice girl in every sense; your dear brother used to admire her very much.”

“Yes, I remember her a little; but Reginald’s tastes and mine were not always similar.”

“Well, Henry, I hope that you will like her. It is a delicate matter to speak about, even for a mother to a son, but you know now how terribly indebted we are to the Levingers, and of course if a way could be found out of our difficulties it would be a great relief to me and to your dear father. Believe me, my boy, I do not care so much about myself; but I wish, if possible, to save him from further sorrow. I think that very little would kill him now.”

“See here, mother,” said Henry bluntly: “Ellen tells me that you wish me to marry Miss Levinger for family reasons. Well, in this matter, as in every other, I will try to oblige you if I can; but I cannot understand what grounds you have for supposing that the young lady wishes to marry me. So far as I can judge, she might take her fortune to a much better market.”

“I don’t quite know about it, Henry,” answered Lady Graves, with some hesitation. “I gathered, however, that, when he came here after you had gone to join your ship about eighteen months ago, Mr. Levinger told your father, with whom you know he has been intimate since they were both young, that you were a fine fellow, and had taken his fancy as well as his daughter’s. Also I believe he said that if only he could see her married to such a man as you are he should die happy, or words to that effect.”

“Rather a slight foundation to build all these plans on, isn’t it, mother? In eighteen months her father may have changed his mind, and Miss Levinger may have seen a dozen men whom she likes better. Here comes Ellen to meet us, so let us drop the subject.”

About six o’clock that afternoon Henry, returning from a walk on the estate, saw a strange dog-cart being run into the coach-house, from which he inferred that Mr. and Miss Levinger had arrived. Wishing to avoid the appearance of curiosity, he went straight to his room, and did not return downstairs till within a few minutes of the dinner-hour.

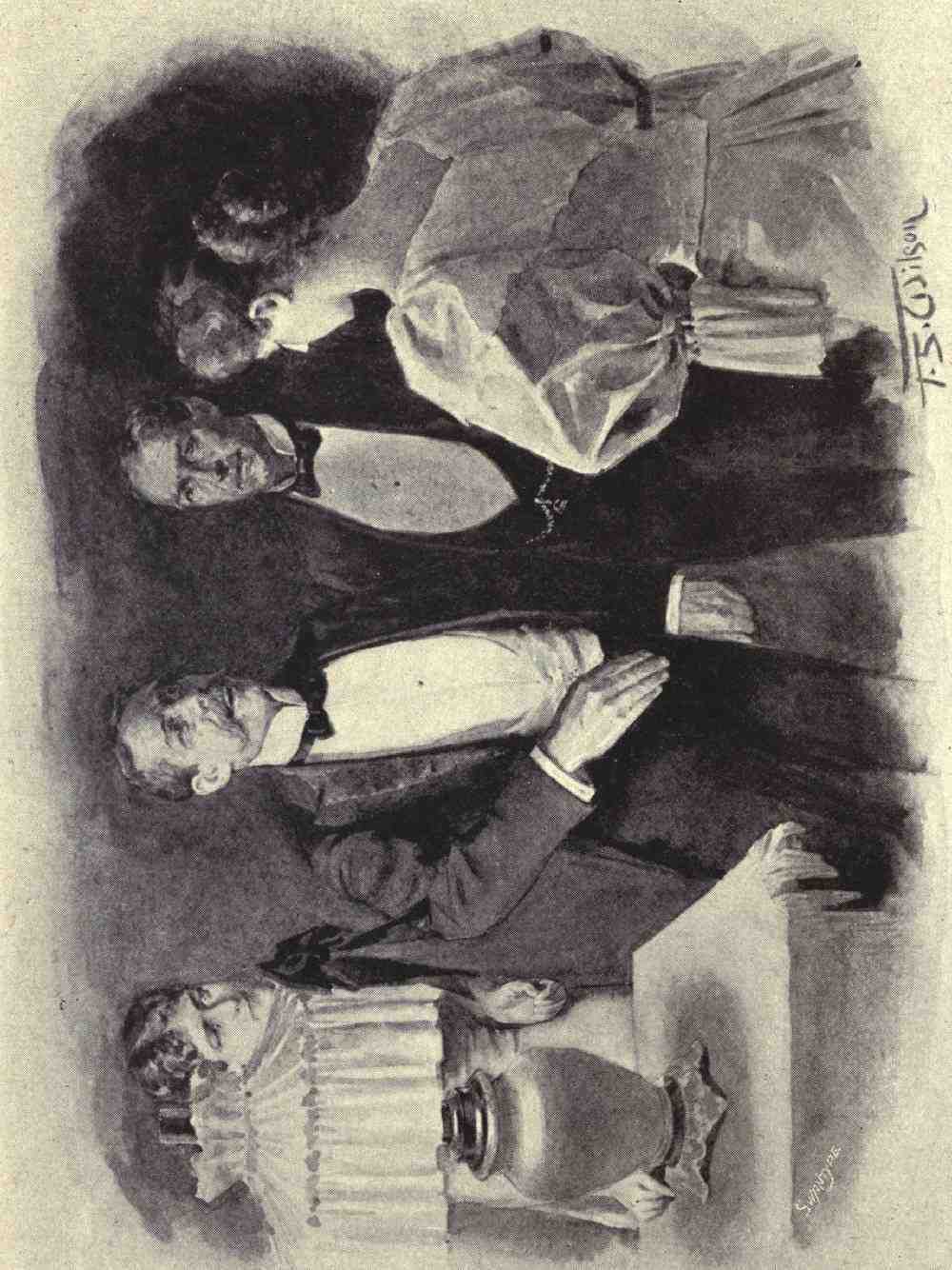

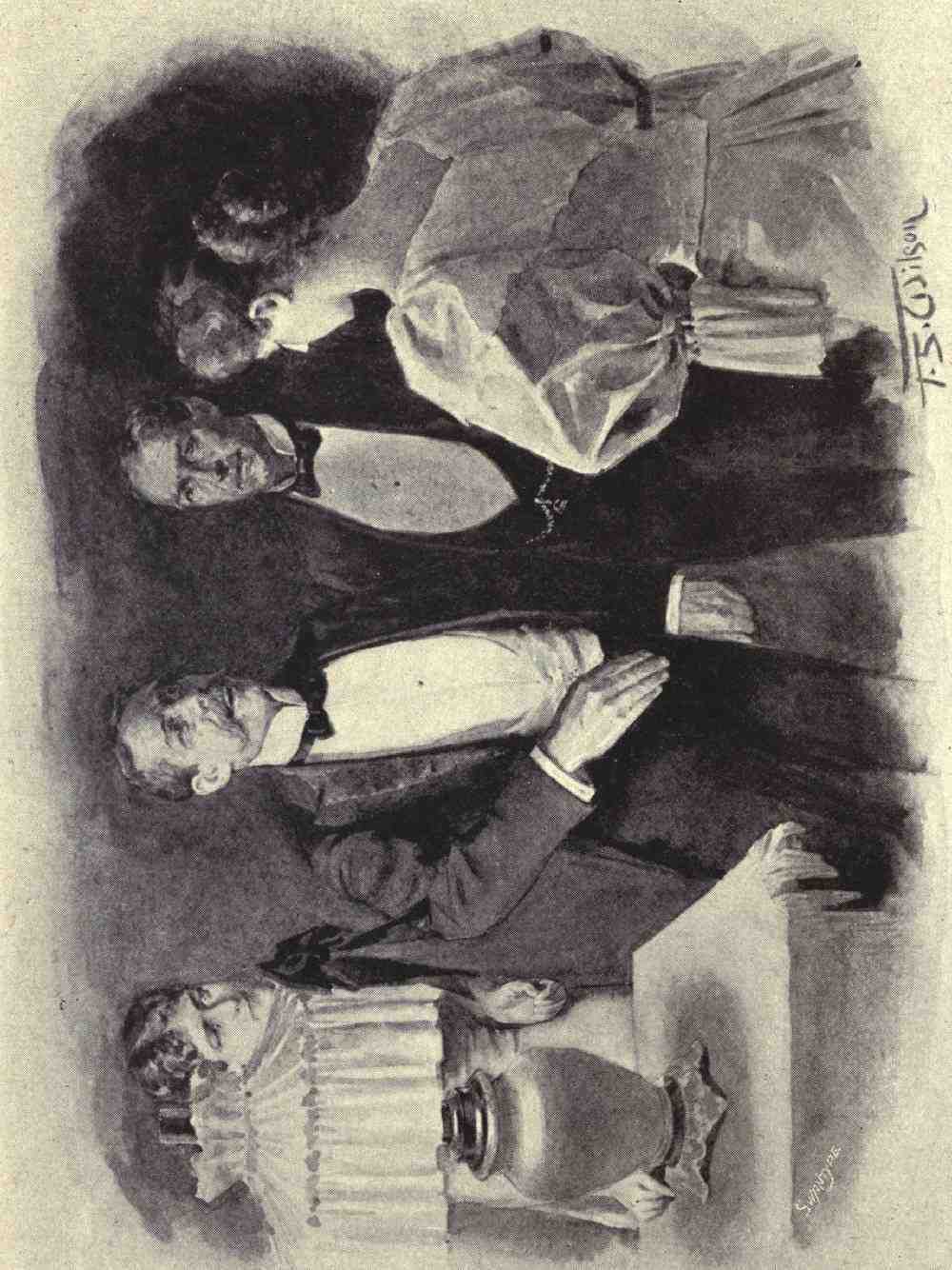

The large and rather ill-lighted drawing-room seemed to be empty when he entered, and Henry was about to seat himself with an expression of relief, for his temper was none of the best this evening, when a rustling in a distant corner attracted his attention. Glancing in the direction of the noise, he perceived a female figure seated in a big arm-chair reading.

“Why don’t you come to the light, Ellen?” he said. “You will ruin your eyes.”

Again the figure rustled, and the book was shut up; then it rose and advanced towards him timidly a delicate figure dressed with admirable taste in pale blue, having flaxen hair, a white face, large and beseeching grey eyes, and tiny hands with tapering fingers. At the edge of the circle of lamp-light the lady halted, overcome apparently by shyness, and stood still, while her pale face grew gradually from white to pink and from pink to red. Henry also stood still, being seized with a sudden and most unaccountable nervousness. He guessed that this must be Miss Levinger in fact, he remembered her face but not one single word could he utter; indeed, he seemed unable to do anything except regret that he had not waited upstairs till the dinner-bell rang. There is this to be said in excuse of his conduct, that it is somewhat paralysing to a modest man unexpectedly to find himself confronted by the young woman whom his family desire him to marry.

“How do you do?” he ejaculated at last: “I think that we have met before.” And he held out his hand.

“Yes, we have met before,” she answered shyly and in a low voice, touching his sun-browned palm with her delicate fingers, “when you were at home last Christmas year.”

“It seems much longer ago than that,” said Henry, “so long that I wonder you remember me.”

“I do not see so many people that I am likely to forget one of them,” she answered, with a curious little smile. “I dare say that the time seemed long to you, abroad in new countries; but to me, who have not stirred from Monk’s Lodge, it is like yesterday.”

“Well, of course that does make a difference;” then, hastening to change the subject, he added, “I am afraid I was very rude; I thought that you were my sister. I can’t imagine how you can read in this light, and it always vexes me to see people trying their eyes. If you had ever kept a night watch at sea you would understand why.”

“I am accustomed to reading in all sorts of lights,” Emma answered.

“Do you read much, then?”

“I have nothing else to do. You see I have no brothers or sisters, no one at all except my father, who keeps very much to himself; and we have few neighbours round Monk’s Lodge—at least, few that I care to be with,” she added, blushing again.

Henry remembered hearing that the Levingers were considered to be outside the pale of what is called society, and did not pursue this branch of the subject.

“What do you read?” he asked.

“Oh, anything and everything. We have a good library, and sometimes I take up one class of reading, sometimes another; though perhaps I get through more history than anything else, especially in the winter, when it is too wretched to go out much. You see,” she added in explanation, “I like to know about human nature and other things, and books teach me in a second-hand kind of way,” and she stopped suddenly, for just then Ellen entered the room, looking very handsome in a low-cut black dress that showed off the whiteness of her neck and arms.

‘So we meet at last.’

“What, are you down already, Miss Levinger!” she said, “and with all your things to unpack too. You do dress quickly,” and she looked critically at her visitor’s costume. “Let me see: do you and Henry know each other, or must I introduce you?”

“No, we have met before,” said Emma.

“Oh yes! I remember now. Surely you were here when my brother was on leave last time.” At this point Henry smiled grimly and turned away to hide his face. “There is not going to be any dinner-party, you know. Of course we couldn’t have one even if we wished at present, and there is no one to ask if we could. Everybody is in London at this time of the year. Mr. Milward is positively the only creature left in these parts, and I believe mother has asked him. Ah! here he is.”

As she spoke the butler opened the door and announced —“Mr. Milward.”

Mr. Milward was a tall and good-looking young man, with bold prominent eyes and a receding forehead, as elaborately dressed as the plain evening attire of Englishmen will allow. His manner was confident, his self-appreciation great, and his tone towards those whom he considered his inferiors in rank or fortune patronising to the verge of insolence. In short, he was a coarse-fibred person, puffed up with the pride of his possessions, and by the flattery of women who desired to secure him in marriage, either themselves or for some friend or relation.

“What an insufferable man!” was Henry’s inward comment, as his eyes fell upon him entering the room; nor did he change his opinion on further acquaintance.

“How do you do, Mr. Milward?” said Ellen, infusing the slightest possible inflection of warmth into her commonplace words of greeting. “I am so glad that you were able to come.”

“How do you do, Miss Graves? I had to telegraph to Lady Fisher, with whom I was going to dine to-night in Grosvenor Square, to say that I was ill and could not travel to town. I only hope she won’t find me out, that is all.”

“Indeed!” answered Ellen, with a touch of irony: “Lady Fisher’s loss is our gain, though I think that you would have found Grosvenor Square more amusing than Rosham. Let me introduce you to my brother, Captain Graves, and to Miss Levinger.”

Mr. Milward favoured Henry with a nod, and turning to Emma said, “Oh! how do you do, Miss Levinger? So we meet at last. I was dreadfully disappointed to miss you when I was staying at Cringleton Park in December. How is your mother, Lady Levinger? Has she got rid of her neuralgia?”

“I think that there is some mistake,” said Emma, visibly shrinking before this bold, assertive man: “I have never been at Cringleton Park in my life, and my mother, Mrs. Levinger, has been dead many years.”

“Oh, indeed: I apologise. I thought you were Miss Levinger of Cringleton, the great heiress who was away in Italy when I stayed there. You see, I remember hearing Lady Levinger say that there were no other Levingers.”

“I am afraid that I am a living contradiction to Lady Levinger’s assertion,” answered Emma, flushing and turning aside.

Ellen, who had been biting her lip with vexation, was about to intervene, fearing lest Mr. Milward should make further inquiries, when the door opened and Mr. Levinger entered, followed by her father and mother. Henry took the opportunity of shaking hands with Mr. Levinger to study his appearance somewhat closely—an attention that he noticed was reciprocated.

Mr. Levinger was now a man of about sixty, but he looked much older. Either because of an accident, or through a rheumatic affection, he was so lame upon his right leg that it was necessary for him to use a stick even in walking from one room to another; and, although his hair was scarcely more than streaked with white, frailty of health had withered him and bowed his frame. Looking at him, Henry could well believe what he had heard that five-and-twenty years ago he was one of the handsomest men in the county. To this hour the dark and sunken brown eyes were full of fire and eloquence—a slumbering fire that seemed to wax and wane within them; the brow was ample, and the outline of the features flawless. He seemed a man upon whom age had settled suddenly and prematurely—a man who had burnt himself out in his youth, and was now but an ash of his former self, though an ash with fire in the heart of it.

Mr. Levinger greeted him in a few courteous, well-chosen words, that offered a striking contrast to the social dialect of Mr. Milward,—the contrast between the old style and the new,—then, with a bow, he passed on to offer his arm to Lady Graves, for at that moment dinner was announced. As Henry followed him with Miss Levinger, he found himself wondering, with a curiosity that was unusual to him, who and what this man had been in his youth, before he drifted a waif to Bradmouth, there to repair his broken fortunes by a mésalliance with the smack owner’s daughter.

“Was your father ever in the Army?” he asked of Emma, as they filed slowly down the long corridor. “Forgive my impertinence, but he looks like a military man.”

He felt her start at his question.

“I don’t know: I think so,” she answered, “because I have heard him speak of the Crimea as though he had been present at the battles; but he never talks of his young days.”

Then they entered the dining-room, and in the confusion of taking their seats the conversation dropped.