CHAPTER XVIII.

CONGRATULATIONS.

Joan was not really ill: she had contracted a chill, accompanied by a certain amount of fever, but this was all. Indeed, the fever had already taken her on the night of her love scene with Henry, and to its influence upon her nerves may be attributed a good deal of the conduct which to Lady Graves had seemed to give evidence of art and experienced design. Nothing further was said by her aunt as to her leaving the house, and things went on as usual till the morning when she woke up and learned that her lover had gone under such sad circumstances. It was a shock to her, but she grieved more for him than for herself. Indeed, she thought it best that he should be gone; it even seemed to her that she had anticipated it, that she had always known he must go and that she would see him no more. The curtain was down for ever; her short tragedy had culminated and was played out, so Joan believed, unaware that its most moving acts were yet to come. It was terrible, and henceforth her life must be a desolation; but it cannot be said that as yet her conscience caused her to grieve for what had been: sorrow and repentance were to overtake her when she learned all the trouble and ruin which her conduct had caused.

No, at present she was glad to have met him and to have loved him, winning some share of his love in return; and she thought then that she would rather go broken-hearted through the remainder of her days than sponge out those memories and be placid and prosperous without them. Whatever might be her natural longings, she had no intention of carrying the matter any further, least of all had she any intention of persuading or even of allowing Henry to marry her, for she had been quite earnest and truthful in her declarations to him upon this point. She did not even desire that his life should be burdened with her in any way, or that she should occupy his mind to the detriment of other persons and affairs; though of course she hoped that he would always think of her with affection, or perhaps with love, and she would have been no true woman had she not done so. Curiously enough, Joan seemed to expect that Henry would adopt the same passive attitude towards herself which she contemplated adopting towards him. She knew that men are for the most part desirous of burying their dead loves out of sight—sometimes, in their minds, marking the graves with a secret monument visible to themselves alone, be it a headstone with initials and a date, or only a withered wreath of flowers; but more often suffering the naked earth of oblivion to be trodden hard upon them, as though fearful lest their poor ghosts should rise again, and, taking flesh and form, come back to haunt a future in which they have no place.

She did not understand that Henry was not of this class, that in many respects his past life had been different to the lives of the majority of men, or that she was absolutely the first woman who had ever touched his heart. Therefore she came to the conclusion, sadly enough, and with an aching jealousy which she could not smother, but with resignation, that the next important piece of news she was likely to hear about her lover would be that of his engagement to Miss Levinger.

As it chanced, tidings of a totally different nature reached her on the following day, though whether they were true or false she could not tell. It was her aunt who brought them, when she came in with her supper, for Joan was still confined to her room.

“There are nice doings up there at Rosham,” said Mrs. Gillingwater, eyeing her niece curiously.

Joan’s heart gave a leap.

“What’s the matter?” she asked, trying not to look too interested.

“Well, the old baronet is gone for one thing, as was expected that he must; and they say that he slipped off while he was cursing and swearing at his son, the Captain, which don’t seem a right kind of way to die, to my mind.”

“Died cursing and swearing at Captain Graves? Why?” murmured Joan faintly.

“I can’t tell you rightly. All I know about it came to me from Lucilla Smith, who is own sister to Mary Roberts, the cook up there, who, it seems, was listening at the door, or, as she puts it, waiting to be called in to say good-bye to her master, and she had it from the gardener’s boy.”

“She? Who had it, aunt?”

“Why, Lucilla Smith had, of course. Can’t you understand plain English? I tell you that old Sir Reginald sat up in bed and cursed and swore at the Captain till he was black in the face. Then he screeched out loud and died.”

“How dreadful!” said Joan. “But what was he cursing about?”

“About? Why, because the Captain wouldn’t promise to marry Miss Levinger, who’s got bonds on all the property, down to the plate in the pantry, in her pocket. That old fox of a father of hers stole them when he was agent there, I expect——” Here Mrs. Gillingwater checked herself, and added hastily, “But that’s neither here nor there; at any rate she’s got them, and can sell the Graves’s up to-morrow if she likes, which being so, it ain’t wonderful that old Sir Reginald cursed when he heard his son turn round coolly and say that he wouldn’t marry her at any price.”

“Did he tell why he wouldn’t marry her?” asked Joan, with a desperate effort to look unconcerned beneath her aunt’s searching gaze.

“I don’t know that he did. If so, Lucilla doesn’t know, so I suppose that Mary Roberts couldn’t hear. She did hear one thing, however: she heard your name, miss, twice, so there wasn’t no mistake about it.”

“My name? Oh! my name!” gasped Joan.

“Yes, yours, unless there is another Joan Haste in these parts, which I haven’t heard on. And now, perhaps, you will tell me what it was doing there.”

“How can I tell you when I don’t know, aunt?”

“How can you tell me when you won’t say, miss? That’s what you mean. Look here, Joan: do you take me for a fool? Do you suppose that I haven’t seen through your little game? Why, I have watched it all along, and I’m bound to say that you don’t play half so bad for a young hand. Well, it seems that you pulled it off this time, and I’m not saying but what I am proud of you, though I still hold that you would have done better to have married Samuel; for I believe, when all is said and finished, he will be the richer man of the two. It’s very nice to be a baronet’s lady, no doubt; but if you have nothing to live on—and I don’t fancy that there are many pickings left up there at Rosham—I can’t see that it helps you much forrarder.”

“What do you mean, aunt?”

“Mean? Now, Joan, don’t you begin trying your humbug on me: keep that for the men. You’re not going to pretend that you haven’t been making love to the Captain—I beg his pardon, Sir Henry he is now—as hard as you know how. Well, it seems that you have bamboozled him finely, and have made him so sweet on your pretty face that he’s going to throw over marrying the Levinger girl in order to marry you, for that’s what it comes to, and you may very well be proud of it. But don’t you be carried away; you wouldn’t take my advice about Samuel Rock, and I spoke to you rough that night on purpose, for I wanted you to make sure of one or the other. Well, take my advice about Sir Henry. Remember there is many a slip between the cup and the lip, and that out of sight is apt to be out of mind. Don’t you keep out of sight too long. You strike while the iron is hot, and marry him; on the quiet if you like, but marry him. Of course there will be a row, but all the rows under heaven can’t unmake a wife and a ladyship. Now listen to me. I have gone out of my way to talk to you like this, because you are a fine girl and I’m fond of you, which is more than you are of me, and I should like to see you get on in the world; and perhaps when you’re up you will not forget your old aunt who is down. I tell you I have gone out of my way to give you this tip, for there’s some as won’t be pleased to see you turned into Lady Graves. Yes, there’s some who’d give a good deal to stop it: Samuel Rock, for instance; he don’t like parting, but he’d lay down something handsome, and I doubt if I’ll ever see the coin out of you that I might out of him and others, for after all you won’t be a rich woman at best. However, we must sacrifice ourselves at times, and that’s what I am doing on your account, Joan. And now, if you want to get a note up to Rosham, I will manage it for you. But perhaps you had better wait and go yourself.”

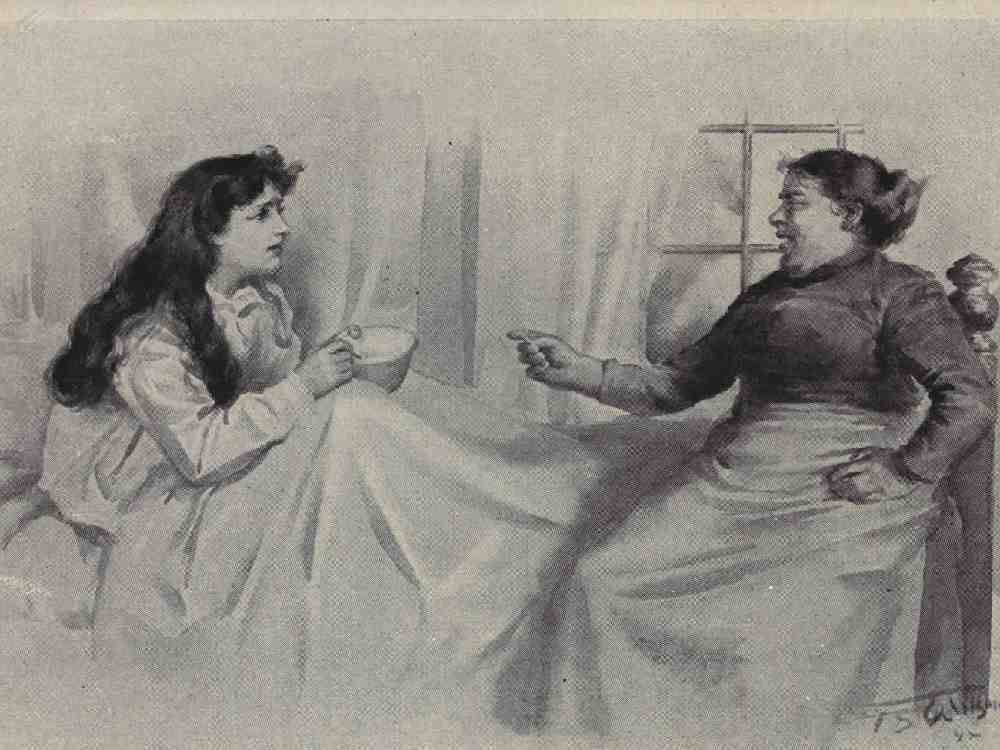

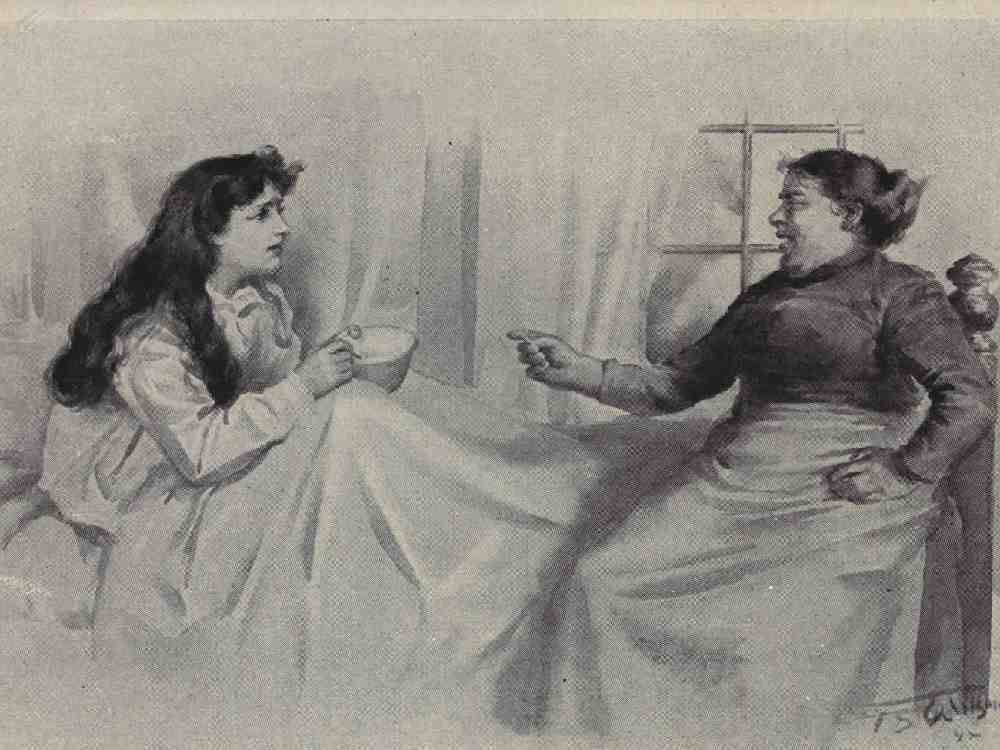

‘“My name? Oh! my name!” gasped Joan.’

Joan listened to this long address in amazement mingled with scorn. It would be hard to say which of its qualities disgusted her the most—its coarseness, its cunning, or its avarice. Above all these, however, it revolted her to learn that her aunt thought her capable of conceiving and carrying out so disgraceful a plot. What must the woman’s mind be like, that she could imagine such evil in others? And what had she, Joan, ever done, that she should be so misunderstood?

“I don’t understand you, aunt: I don’t wish to marry Captain Graves,” she said simply.

“Do you mean to tell me that you ain’t blind gone on him, and that he’s not gone on you, Joan?”

“I said that I did not wish to marry him,” she answered, evading the question. “To marry a girl like me would be the ruin of him.”

Mrs. Gillingwater stared at her niece as she lay on the bed before her; then she burst into a loud laugh.

“Oho! you’re a simple one, you are,” she said, pointing her finger at her. “You’re downright innocent, if ever a girl was, with your hands folded and your hair hanging about your face, like a half-blown angel, more fit for a marble monument than for this wicked world. You couldn’t give anybody a kiss on the quiet, could you? Your lips would blush themselves off first, wouldn’t they? And as for marrying him if his ma didn’t like it, that you’d never, never do. I’ll tell you what it is, Joan: I’m getting a better opinion of you every day; you ain’t half the fool I thought you, after all. You remember what I said to you about Samuel, and you think that I’ve got his money in my pocket and other people’s too perhaps, and that I’m just setting a trap for you and going to give you away. Well, as a matter of fact I wasn’t this time, so you might just as well have been open with me. But there you are, girl: go about your own business in your own fashion. I see that you can be trusted to look after yourself, and I won’t spoil sport. I’ve been blind and deaf and dumb before now—yes, blinder than you think, perhaps, for all your psalm-singing air—and I can be again. And now I’m off; only I tell you fair I won’t work for nothing, so don’t you begin to whine about poor relations when once you’re married, else I may find a way to make it hot for you yet, seeing that there’s things you mightn’t like spoken of when you’re ‘my lady’ and respectable.” And with this jocular threat on her lips Mrs. Gillingwater vanished.

When her aunt had gone, Joan drew the sheet over her face as though she sought to hide herself, and wept in the bitterness of her shame. She was what she was; but did she deserve to be spoken to like this? She would rather a hundred times have borne her aunt’s worst violence than be made the object of her loathly compliments. How much did this woman know? Surely everything, or she would not dare to address her as she had done. She had no longer any respect for her, and that must be the reason of her odious assumption that there was nothing to choose between them, that they were equal in evil. She would not believe her when she said that she had no wish to marry Henry—she thought that the speech was dictated by a low cunning like her own. Well, perhaps it was fortunate that she did not believe her; for, if she had, what would have happened?

Very soon it became clear to Joan that on this point it would be best not to undeceive her aunt, since to do so might provoke some terrible catastrophe of which she could not foresee the consequences. After further reflection, another thing became clear to her: that she must vanish from Bradmouth. What was truth and what was falsehood in Mrs. Gillingwater’s story, she could not say, but obviously it contained an alloy of fact. There had been some quarrel between Henry and his dying father, and in that quarrel her name had been mentioned. Strange as it seemed, it might even be that he had declared an intention of marrying her. Now that she thought of it, she remembered that he had spoken of such a thing several times. The idea opened new possibilities to her—possibilities of a happiness of which she had not dared to dream; but, to her honour be it said, she never allowed them to take root in her mind—no, not for a single hour. She knew well what such a marriage would mean for Henry, and that was enough. She must disappear; but whither? She had no means and no occupation. Where, then, could she go?

For two or three days she stayed in her room, keeping her aunt as much at a distance as possible, and pondering on these matters, but without attaining to any feasible solution of them.

On the day of Sir Reginald’s funeral, which Mrs. Gillingwater attended, and of which she gave her a full account, she received Henry’s message brought to her by the doctor, and returned a general answer to it. Next morning her uncle Gillingwater, who chanced to be sober, brought her word that Mr. Levinger had called, and asked that she would favour him with a visit at Monk’s Lodge so soon as she was about again. Joan wondered for what possible reason Mr. Levinger could wish to see her, and her conscience answered that it had to do with Henry. Well, if he was not her guardian, he took an undefined interest in her, and it occurred to her that he might be able to help her to escape from Bradmouth, so for this reason, if for no other, she determined to comply with his wish.

Two days later, accordingly, Joan started for Monk’s Lodge, having arranged with the local grocer to give her a lift to the house, whither his van was bound to deliver some parcels; for, after being laid up, she did not feel equal to walking both ways. About two o’clock, arrayed in her best grey dress, she went to the grocer’s shop and waited outside. Presently she heard a shrill voice calling to her from the stable-yard, that joined the shop, and a red-haired boy poked his head through the open door.

“Sorry to keep you waiting, Joan Haste,” said the boy, who was none other than Willie Hood; “but I’ve been cleaning up the old horse’s bit in honour of having such a swell as you to drive. Stand clear now; here we come.” And he led out the van, to which a broken-kneed animal was harnessed, that evidently had seen better days.

“Why, you’re never going to drive me, Willie, are you?” asked Joan in alarm, for she remembered the tale of that youth’s equestrian efforts.

“Yes, I am, though. Don’t you be skeered. I know what you’re thinking of; but I’ve been grocer’s boy for a month now, and have learned all about hosses and how to ride and drive them. Come, up you get, unless you’d rather walk behind.”

Thus adjured, Joan did get up, and they started. Soon she perceived that her fears as to Willie Hood’s powers of driving were not ill-founded; but, fortunately, the animal that drew them was so reduced in spirit that it did not greatly matter whether any one was guiding him or no.

“Is he all right again?” said Willie presently, as, leaving the village, they began to travel along the dusty road that lay like a ribbon upon the green crest of the cliff.

“Do you mean Captain Graves?”

“Yes: who else? I saw him as they carried him into the Crown and Mitre that night. My word! he did look bad, and his trouser was all bloody too. I never seed any one so bloody before; though, now I come to think of it, you were bloody also, just like people in a story-book. That was a bad beginning for you both, they say.”

“He is better; but he is not all right,” answered Joan, with a sigh. Why would every one talk to her about Henry? “Captain Graves is not here now, you know.”

“No; he’s up at the Hall. And the old Squire is dead and buried. I went to see his funeral, I did. It was a grand sight—such lots of carriages, and such a beautiful polished coffin, with a brass cross and a plate with red letters on it. I’d like to be buried like that myself some day.”

Joan smiled, but made no answer; and there was silence for a little time, while Willie thrashed the horse till his face was the colour of his hair.

“I say, Joan,” he said, when at last that long-suffering animal broke into a shuffling trot, which caused the dust to rise in clouds, “is it true that you are going to marry him?”

“Marry Sir Henry Graves! Of course not. What put that idea into your head, you silly boy?”

“I don’t know; it’s what folks say, that’s all. At least, they say that if you don’t you ought to—though I don’t rightly understand what they mean by that, unless it is that you are pretty enough to marry anybody, which I can see for myself.”

Joan blushed crimson, and then turned pale as the dust.

“No need to pink up because I pay you a compliment, Joan,” said Willie complacently.

“Folks say?” she gasped. “Who are the folks that say such things?”

“Everybody mostly—mother for one. But she says that you’re like to find yourself left on the sand with the tide going out, like a dogfish that’s been too greedy after sprats, for all that you think yourself so clever, and are so stuck-up about your looks. But then mother never did like a pretty girl, and I don’t pay no attention to her—not a mite; and if I was you, Joan, I’d just marry him to spite them.”

“Look here, Willie,” answered Joan, who by now was almost beside herself: “if you say another word about me and Sir Henry Graves, I’ll get out and walk.”

“Well, I dare say the old horse would thank you if you did. But I don’t see why you should take on so just because I’ve been answering your questions. I expect it’s all true, and that you do want to marry him, or else you’re left on the beach like the dogfish. But if you are, it’s no reason why you should be cross with me.”

“I’m not cross, Willie, I am not indeed; but you don’t understand that I can’t bear this kind of gossip.”

“Then you’d better get out of Bradmouth as fast as you can, Joan, for you’ll have lots of it to bear there, I can tell you. Why, I’m downright sick of it myself,” answered the merciless Willie. Then he lapsed into a dignified silence, that for the rest of the journey was only broken by his exhortations to the sweating horse, and the sound of the whacks which he rained upon its back.

At length they reached Monk’s Lodge, and drove round to the side entrance, where Joan got down hurriedly and walked to the servants’ door.