CHAPTER XXV.

“I FORBID YOU.”

On the following Monday morning Joan began her career as a shop-girl, to describe which in detail would be too long, however instructive it might prove. Her actual work, especially at this, the dead season of the year, was not so hard as she had expected, nor was she long in mastering her duties; but, accustomed as she had been to a country life and the fresh air, she soon found confinement for so many hours a day in the close atmosphere of the shop exceedingly irksome. From Kent Street to Messrs. Black and Parker’s was but a quarter of an hour’s walk; and, as Joan discovered by experiment, without exposing herself to many annoyances it was impossible for her to wander about the streets after dark in search of exercise. As a last resource she was driven to rising at the peep of day and taking her walks abroad in the Park so soon as the gates were open—a daily constitutional which, if wholesome, was not exhilarating, and one that could only be practised in fine weather and while the days were long. This craving for air, however, was among the least of her troubles, for soon it became clear to her that she had no vocation for shop life; indeed, she learned to loathe it and its surroundings. At first the humours of the business amused her a little, but very shortly she discovered that even about these there was a terrible sameness, for one cannot be perpetually entertained by the folly of old ladies trying to make themselves look young, or by the vanity of the young ones neglected by nature and attempting to supply their deficiencies with costly garments.

What galled her chiefly, however, were the attentions with which she was honoured by the young men of the establishment. Worst of all, the oiled and curled Mr. Waters singled her out as the object of his especial admiration, till at length she lost her temper, and answered him in such a fashion as to check his advances once and for all. He left her muttering “You shall pay for that”; and he kept his word, for thenceforth her life was made a misery to her, and it seemed that she could do nothing right. As it chanced, he could not actually discharge her, for Joan had attracted the favourable notice of one of the owners of the business, who, when Mr. Waters made some trumped-up complaint against her, dismissed it with a hint that he had better be more careful as to his facts in future.

For the rest, she had no amusements and no friends, and during all the time she spent in London she never visited a theatre or other place of entertainment. Her only recreation was to read when she could get the books, or, failing this, to sit with little Mrs. Bird in the Kent Street parlour and perfect herself in the art of conversation with the deaf and dumb.

As may be imagined, such an existence did not tend to cause Joan to forget her past, or the man who was to her heart what the sun is to the world. She could renounce him, she could go away vowing that she would never see him more; but to live without him, and especially to live such a life as hers, ah! that was another matter.

Moreover, as time went on, a new terror took her, that, vague in the beginning, grew week by week more definite and more dreadful. At first she could scarcely believe it, for somehow such a thing had never entered into her calculations; but soon she was forced to acknowledge it as a fact, an appalling, unalterable fact, which, as yet secret to herself, must shortly become patent to the whole world. The night that the truth came home to her without the possibility of further doubt was perhaps the most terrible which she ever spent. For some hours she thought that she must go mad: she wept, she prayed, she called upon the name of her lover, who, although he was the author of her woe, in some mysterious fashion had now grown doubly dear to her, till at last sleep or insensibility brought her relief. But sleep passes with the darkness, and she awoke to find this new spectre standing by her bedside and to know that there it must always stand till the end came. All that day she went about her work dazed by her secret agony of mind, but in the evening her senses seemed to come back to her, bringing with them new and acuter suffering.

Where was she to go and what was she to do, she who had no friend in the wide world, or at least none in whom she could confide? Soon they would turn her out upon the streets; even the Bird family would shrink from her as though she had a leprosy. Would it not be better to end it at once, and herself with it? Abandoning her usual custom, Joan did not return home, but wandered about London heedless of the stares and insults of the passers-by, till at length she came to Westminster Bridge. She had not meant to come there—indeed, she did not know the way—but the river had drawn her to its brink, as it has drawn so many an unfortunate before her. There beneath those dim and swirling waters she could escape her shame and find peace, or at least take it to a region beyond all familiar things, whereof the miseries and unrest would not be those of the earth, even if they surpassed them. Twice she crossed the bridge; once she tore herself away, walking for a while along the Embankment; then she returned to it again, brought back by the irresistible attraction of the darkling river.

Now she thought that she would do it, and now her hand was on the parapet. She was quite alone for the moment, there were none to stop her,—alone with her fear and fate. Yes, she would do it: but oh! what of Henry? Had she a right to make him a murderer? Had she the right to be the murderess of his child? What would he say when he heard, and what would he think? After all, why should she kill herself? Was it so wicked to become a mother? According to religion and custom, yes—that is, such a mother as she would be—but how about nature? As for the sin, she could not help it. It was done, and she must suffer for it. She had broken the law of God, and doubtless God would exact retribution from her; indeed, already He was exacting it. At least she might plead that she loved this man, and there were many married women who could bear their children without shame, and could not say as much. Yet they were virtuous and she was an outcast—that was the rule. Well, what did it matter to her? They could not put her in prison, and she had no name to lose. Why should she kill herself? Why should she not bear her baby and love it for its father’s sake and its own? Now she came to think of it, there was nothing that she would like better. Doubtless there would be difficulties and troubles, but she was answerable to no one. However much she might be ashamed of herself, there were none to be ashamed of her, and therefore it was a mere question of pounds, shillings and pence. She could get these from Mr. Levinger, or, failing him, from Henry. He would not leave her to starve, or his child either—she knew him too well for that. What a fool she had been! Had she not come to her senses, by now she would be floating on that river or lying in the mud at the bottom of it. Well, she had done with that, and so she might as well go home. The future and the wrath of Heaven she must face, that was all; she had sown, and she must reap—as we always do.

Accordingly she hailed a passing hansom and told the driver to take her to the Marble Arch, for she was too weary to walk; moreover she did not know the road.

It was ten o’clock when she reached Kent Street. “My dear,” said Mrs. Bird, “how flushed you look! Where have you been? We were all getting quite anxious about you.”

“I have been walking,” answered Joan: “I could not stand the heat of that shop any longer, and I felt as though I must get some exercise or faint.”

“I do not think that young women ought to walk about the streets by themselves at night,” said Mrs. Bird reprovingly. “If you were so very anxious for exercise I dare say that I could have managed to accompany you. Have you had supper?”

“No, and I don’t want any. I think that I will go to bed. I am tired.”

“You will certainly not go to bed, Joan, until you have had something to eat. I don’t know what has come to you—I don’t indeed.”

So Joan was forced to sit down and go through the farce of swallowing some food, while Sally ministered to her, and Jim, perceiving that something was wrong, smiled sympathetically across the table. How she got through the meal she never quite knew, for her mind was somewhat of a blank; though she could not help wondering vaguely what these good people would say, could they become aware that within the last hour she had been leaning on the parapet of Westminster Bridge purposing to cast herself into the Thames.

Next morning Joan went to her work as usual. All day long she stood in the shop attending to her duties, but it seemed to her as though she had changed her identity, as though she were not Joan Haste, but a different woman, whom as yet she could not understand. Once before she had suffered this fancied change of self: on that night when she lay in the churchyard clasping Henry’s shattered body to her breast; and now again it was with her. That was the hour when she had passed from the regions of her careless girlhood into love’s field of thorns and flowers—the hour of dim and happy dream. This, the second and completer change, came upon her in the hour of awakening; and though the thorns still pierced her soul, behold, the red bloom she had gathered was become a bitter fruit, a very apple of Sodom, a fruit of the tree of sinful knowledge that she must taste of in the wilderness which she had won. Love had been with her in the field, and still he was with her in the desert; but oh! how different his aspect! Then he was bright and winged and beautiful, with lips of honey, and a voice of promise murmuring many a new and happy word; now he appeared terrible and stern, and spoke of sin, of sorrow, and of shame. Then also her lover had been at her side, now she was utterly alone, alone with the accusing angel of her conscience, and in this solitude she must suffer, with no voice to cheer her and no hand to help.

From the hour of their parting she had longed for him, and desired the comfort of his presence. How much more, then, did she long for him now! Soon indeed this craving swallowed up every other need of her nature, and became a physical anguish that, like some deadly sickness, ended in the conquest of her mind and body. Joan fought against it bravely, for she knew what submission meant. It meant that she would involve Henry in her own ruin. She remembered well what he had said about marrying her, and the tale which she had heard as to his refusing to become engaged to Miss Levinger on the ground that he considered himself to be already bound to her. If she told him of her sore distress, would he not act upon these declarations? Would he not insist upon making her his wife, and could she find the strength to refuse his sacrifice? Beyond the barrier that she herself had built between them were peace and love and honour for her. But what was there for him? If once those bars were down—and she could break them with a touch—she would be saved indeed, but Henry must be lost. She was acquainted with the position of his affairs, and aware that the question was not one of a mésalliance only. If he married her, he would be ruined socially and financially in such a fashion that he could never lift up his head again. Of course even in present circumstances it was not necessary that he should marry her, especially as she would never ask it of him; but if once they met, if once they corresponded even, as she knew well, the whole trouble would begin afresh, and at least there would be an end of his prospects with Miss Levinger. No, no; whatever happened, however great her sufferings, her first duty was silence.

Another week went by, leaving her resolution unchanged; but now her health began to fail beneath the constant strain of her anxieties, and a physical languor that rendered her unfit for long hours of work in a heated shop. Now she lacked the energy to tramp about the Park before her early breakfast; indeed, the advance of autumn, with its rain and fogs, made such exercise impossible. Her first despair, the despair that suggested suicide, had gone by, but then so had the half-defiant mood which followed it. Whatever may have been her faults, Joan was a decent-minded woman, and one who felt her position bitterly. Never for one moment of the day or night could she be free from remorse and care, and the weight of apprehension that seemed to crush all courage out of her. Even if from time to time she could succeed in putting aside her mental troubles, their place was taken by anxieties for the future. Soon she must leave the home that sheltered her, and then where was she to go?

One afternoon, about half-past three o’clock, Joan was standing in the mantle department of Messrs. Black and Parker’s establishment awaiting customers. The morning had been a heavy one, for town was filling rapidly, and she felt very tired. There was, it is true, no fixed rule to prevent Messrs. Black and Parker’s employés from seating themselves when not actually at work; but since a pique had begun between herself and Mr. Waters, in practice Joan found few opportunities of so doing. On two occasions when she ventured to rest thus for a minute, the manager had rated her harshly for indolence, and she did not care to expose herself to another such experience. Now she was standing, the very picture of weariness and melancholy, leaning upon a chair, when of a sudden she looked up and saw before her—Ellen Graves and Emma Levinger. They were speaking.

“Very well, dear,” said Ellen, “you go and buy the gloves while I try on the mantles. I will meet you presently in the doorway.”

“Yes,” said Emma, and went.

Joan’s first impulse was to fly; but flight was impossible, for with Ellen, rubbing his white hands and bowing at intervals, was Mr. Waters.

“I think you asked for velvet mantles, madam, did you not? Now, miss, the velvet mantles—quick, please—those new shapes from Paris.”

Almost automatically Joan obeyed, reaching down cloak after cloak to be submitted to Miss Graves’s critical examination. Three or four of them she put by as unsuitable, but at last one was produced that seemed to take her fancy.

“I should like the young person to try on this one, please,” she said.

“Certainly, madam. Now, miss: no, not that, the other. Where are your wits this afternoon?”

Joan put on the garment in silence, turning herself round to display its perfections, with the vain hope that Ellen’s preoccupation and the gathering gloom in the shop would prevent her from being recognised.

“It is very dark here,” Ellen said presently.

“Yes, madam; but I have ordered them to turn on the electric light. Will you be seated for a moment, madam?”

Ellen took a chair, and began chatting with the manager about the advantages of the employment of electricity in preference to gas in shops, while Joan, with the cloak still on her shoulders, stood before them in the shadow.

Just then she heard a footstep, the footstep of a lame man who was advancing towards them from the stairs, and the sound set her wondering if Henry had recovered from his lameness. Next moment she was clinging to the back of a chair to save herself from falling headlong to the floor, for the man was speaking.

“Are you here, Ellen?” he said: “it is so infernally dark in this place. Oh! there you are. I met Miss Levinger below, and she told me that I should find you upstairs trying on bodices or something.”

“One does not generally try on bodices in public, Henry. What is the matter?”

“Nothing more than usual, only I have made up my mind to go back to Rosham by the five o’clock train, and thought that I would come to see whether you had any message for my mother.”

“Oh! I understood that you were not going till Wednesday, when you could have escorted us home. No, I have no particular message, beyond my love. You may tell her that I am getting on very well with my trousseau, and that Edward has given me the loveliest bangle.”

“I have to go,” answered Henry: “those confounded farms, as usual,” and he sighed.

“Oh! farms,” said Ellen,—“I am sick of farms. I wish that the art of agriculture had never been invented. Thank goodness”—as the electric light sprang out with a sudden glare—“we can see at last. If you have a minute, stop and give me your opinion of this cloak. Taste is one of your redeeming virtues, you know.”

“Well, it is about all the time I have,” he said, glancing at his watch. “Where’s the article?”

“There, before you, on that young woman.”

“Oh!” said Henry, “I see. Charming, I think; but a little long, isn’t it? Now I’m off.”

At this moment, for the first time Ellen saw Joan’s face.

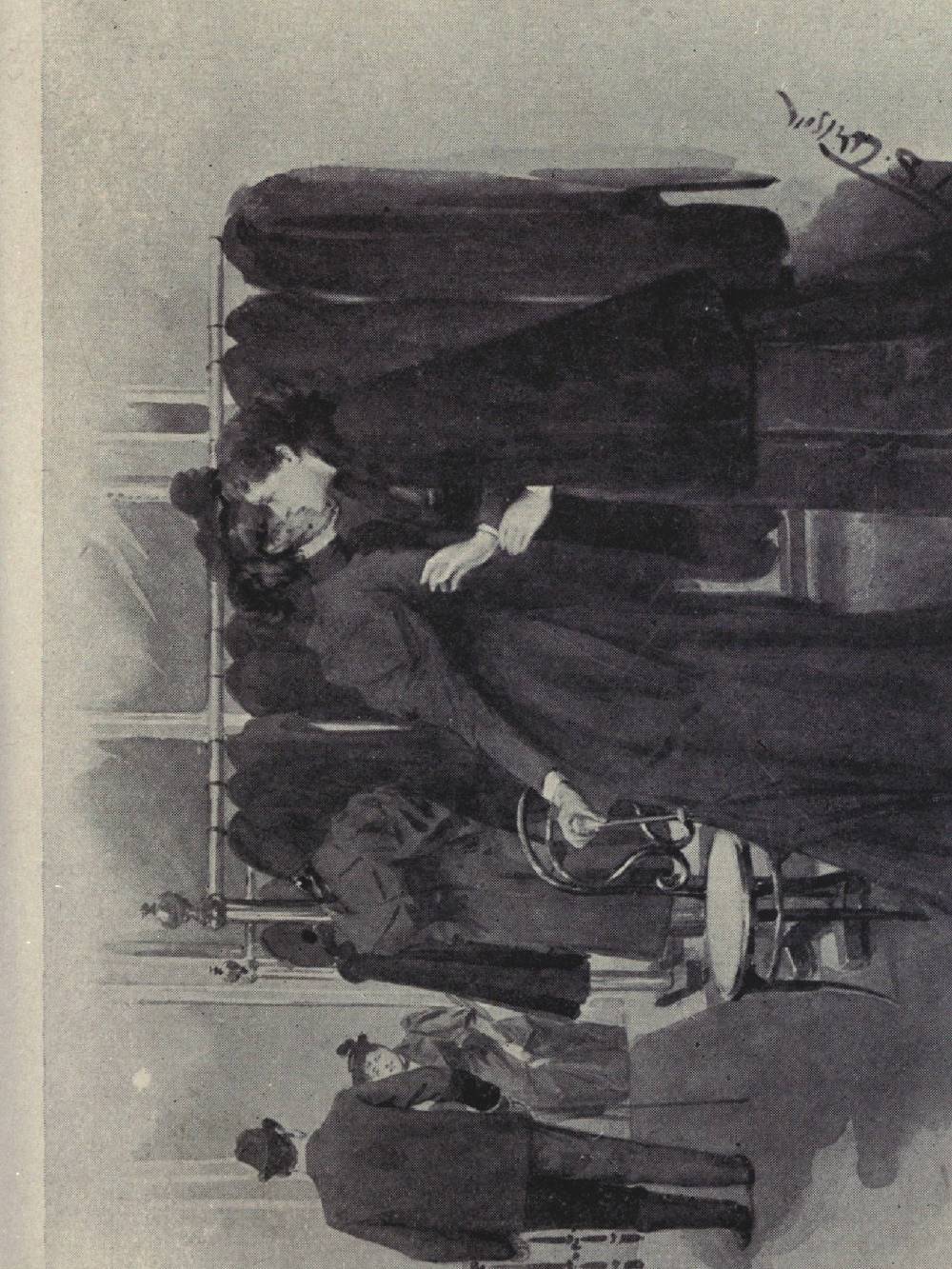

She recognised her instantly—there was no possibility of mistake in that brilliant and merciless light. And what a despairing face it was! so much so, indeed, that it touched even Ellen’s imagination and moved her to pity. The great brown eyes were opened wide, the lips were set apart and pale, the head was bent forward, and from beneath the rich folds of the velvet cloak the hands were a little lifted, as though in entreaty.

In an instant Ellen grasped the facts: Joan Haste had seen Henry, and was about to speak to him. Trying as was the situation, Ellen proved herself its mistress, as she had need to do, for an instinct warned her that if once these two recognised each other incalculable trouble must result. With a sudden movement she threw herself between them.

“Very well, dear,” she said: “good-bye. You had better be going, or you will miss the train.”

“All right,” answered Henry, “there is no such desperate hurry; let me have another look at the cloak.”

“You will have plenty of opportunities of doing that,” Ellen said carelessly; “I have settled to buy it. Why, here comes Emma; I suppose that she is tired of waiting.”

Henry turned and began to walk towards the stairs. Joan saw that he was going, and made an involuntary movement as though to follow him, but Ellen was too quick for her. Stepping swiftly to one side, she spoke, or rather whispered into her ear:

“Go back: I forbid you!”

‘Go back: I forbid you!’

Joan stopped bewildered, and in another moment Henry had spoken some civil words of adieu to Emma and was gone.

“Will you be so good as to send the cloak with the other things?” said Ellen to Mr. Waters. “Come, Emma, we must be going, or we shall be late for the ‘at home,’” and, followed by the bowing manager, she left the shop.

“Oh, my God!” murmured Joan, putting her hands to her face, “oh, my God! my God!”