CHAPTER XXXIII.

THE GATE OF HELL.

On the afternoon of the day following the interview between Lady Graves and Joan, it occurred to Henry, who chanced to be in Bradmouth, that he might as well call at the post-office to get any letters which had been despatched from London on the Sunday. There was but one, and, recognising the handwriting on the envelope, he read it eagerly as he sat upon his horse.

Twice did he read it, then he put it in his pocket and rode homewards wondering, for as yet he could scarcely believe that it had been written by Joan Haste. There was nothing in the letter itself that he could find fault with, yet the tone of it disgusted him. It was vulgar and flippant. Could the same hand have written these words and those other words, incoherent and yet so touching, that had stirred his nature to its depths? and if so, which of them reflected the true mind of the writer? The first letter was mad, but beautiful; the second sane, but to his sense shocking. If it was genuine, he must conclude that the person who penned it, desired to have done with him: but was it genuine? He could not account for the letter, and yet he could not believe in it; for if Joan wrote it of her own free will, then indeed he had misinterpreted her character and thrown his pearls, such as they were, before the feet of swine. She had been ill, she might have fallen under other influences; he would not accept his dismissal without further proof, at any rate until he had seen her and was in a position to judge for himself. And yet he must send an answer of some sort. In the end he wrote thus:—

“DEAR JOAN,—

“I have received your note, and I tell you frankly that I cannot understand it. You say that you do not wish to marry me, which, unless I have altogether misunderstood the situation (as may be the case), seems incomprehensible to me. I still purpose to come to town on Friday, when I hope that you will be well enough to see me and to talk this matter over.

“Affectionately yours,

“HENRY GRAVES.”

Joan received this note in due course of post.

“Just what I expected,” she thought: “how good he is! Most people would have had nothing more to do with me after that horrid, common letter. How am I to meet him if he comes? I cannot—simply I cannot. I should tell him all the truth, and where would my promise be then! If I see him I shall marry him—that is, if he wishes it. I must not see him, I must go away; but where can I go? Oh! Heaven help me, for I cannot help myself!”

The journey to London had not changed Mr. Samuel Rock’s habits, which it will be remembered were of a furtive nature. When Lady Graves saw him on the Sunday, he was employed in verifying the information as to Joan’s address that he had obtained from Mrs. Gillingwater. Any other man would have settled the matter by inquiring at No. 8 as to whether or not she lived there, but he preferred to prowl up and down in the neighbourhood of the house till chance assured him of the fact.

As it happened, Fortune favoured him from the outset, for if Lady Graves saw him, he also saw her as she left the house, and was not slow to draw conclusions from her visit, though what its exact object might be he could not imagine. One thing was clear, however: Mrs. Gillingwater had not lied, since to suppose that by the merest coincidence Lady Graves was calling at this particular house for some purpose unconnected with Joan Haste, was an idea too improbable to be entertained. Still his suspicious mind was not altogether satisfied: for aught he knew Joan had left the place, or possibly she might be dead. In his desire to solve his doubts on these points before he committed himself to any overt act, Samuel returned on the Monday morning to Kent Street from the hotel where he had taken a room, and set himself to watch the windows of No. 8; but without results, for the fog was so thick that he could see nothing distinctly: In the afternoon, when the fog lifted, he was more successful, for, just as the November evening was closing in, the gas was lit in the front room on the first floor, and for a minute he caught a glimpse of Joan herself drawing down a blind. The sight of her filled him with a strange rapture, and he hesitated a while as to whether he should seek an interview with her at once, or wait until the morrow. In the end he decided upon the latter course, both because his courage failed him at the moment, and because he wished to think over his plan of action.

On the Tuesday morning he returned about ten o’clock, and with many inward tremblings rang the bell of No. 8. The door was answered by Mrs. Bird, whom he saluted with the utmost politeness, standing on the step with his hat off.

“Pray, ma’am, is Miss Haste within?” he asked.

“Yes, sir, being so ill, she has not been out for many weeks.”

“So I have heard, ma’am; and I think that you are the lady who has nursed her so kindly.”

“I have done my best, sir: but what might be your errand?”

“I wish to see her, ma’am.”

Mrs. Bird looked at him doubtfully, and shook her head, “I don’t think that she can see any one at present—unless, indeed, you are the gentleman from Bradmouth whom she expects.”

An inspiration flashed into Samuel’s mind. “I am the gentleman from Bradmouth,” he answered.

Again Mrs. Bird scanned him curiously. To her knowledge she had never set eyes upon a baronet, but somehow Samuel did not fulfil her idea of a person of that class. He seemed too humble, and she felt that there was something wrong about the red tie and the broad black hat. “Perhaps he is disguising himself,” she thought: “baronets and earls often do that in books”; then added aloud, “Are you Sir Henry Graves?”

By now Samuel understood that to hesitate was to lose all chance of seeing Joan. His aim was to obtain access to the house; once there, it would be difficult to force him to leave until he had spoken to her. After all he could only be found out, and if he waited for another opportunity, it was obvious that his rival, who was expected at any moment, would be beforehand with him. Therefore he lied boldly, answering,—

“That is my name, ma’am. Sir Henry Graves of Rosham.”

Mrs. Bird asked him into the passage and shut the door.

“I didn’t think you would be here till Friday, sir,” she said, “but I dare say that you are a little impatient, and that your mother told you that Joan is well enough to see you now”; for Mrs. Bird had heard of Lady Graves’s visit, though Joan had not spoken to her of its object.

“Yes, ma’am, you are right: I am impatient very impatient.”

“That is as it should be, sir, seeing all the lost time you have to make up for. Well, the past is the past, and you are acting like a gentleman now, which can never be a sorrow to you, come what may.”

“Quite so, ma’am: but where is Joan?”

“She is in that room at the top of the stairs, sir. Perhaps you would like to go to her now. I know that she is up and dressed, for I have just left her. I do not think that I will come with you, seeing that you might feel it awkward, both of you, if a third party was present at such a meeting. You can tell me how you got on when you come down.”

“Thank you, ma’am,” said Samuel again. And then he crept up the stairs, his heart filled with fear, hope, and raging jealousy of the man he was personating. Arriving at the door, he knocked upon it with a trembling hand. Joan, who was reading Henry’s note for the tenth time, heard the knock, and having hastily hidden the paper in her pocket, said “Come in,” thinking that it was her friend the doctor, for she had caught the sound of a man’s voice in the passage. In another moment the door had opened and shut again, and she was on her feet staring at her visitor with angry, frightened eyes.

“How did you come here, Mr. Rock?” she said in a choked voice: “how dare you come here?”

“I dare to come here, Joan,” he answered, with some show of dignity, “because I love you. Oh! I beg of you, do not drive me away until you have heard me; and indeed, it would be useless, for I shall only wait in the street till I can speak to you.”

“You know that I do not wish to hear you,” she answered; “and it is cowardly of you to hunt me down when I am weak and ill, as though I were a wild beast.”

“I understand, Joan, that you are not too ill to see Sir Henry Graves; surely, then, you can listen to me for a few minutes; and as for my being cowardly, I do not care if I am though why a man should be called a coward because he comes to ask the woman he loves to marry him, I can’t say.”

“To marry you!” exclaimed Joan, turning pale and sinking back into her chair; “I thought that we had settled all that long ago, Mr. Rock, out by the Bradmouth meres.”

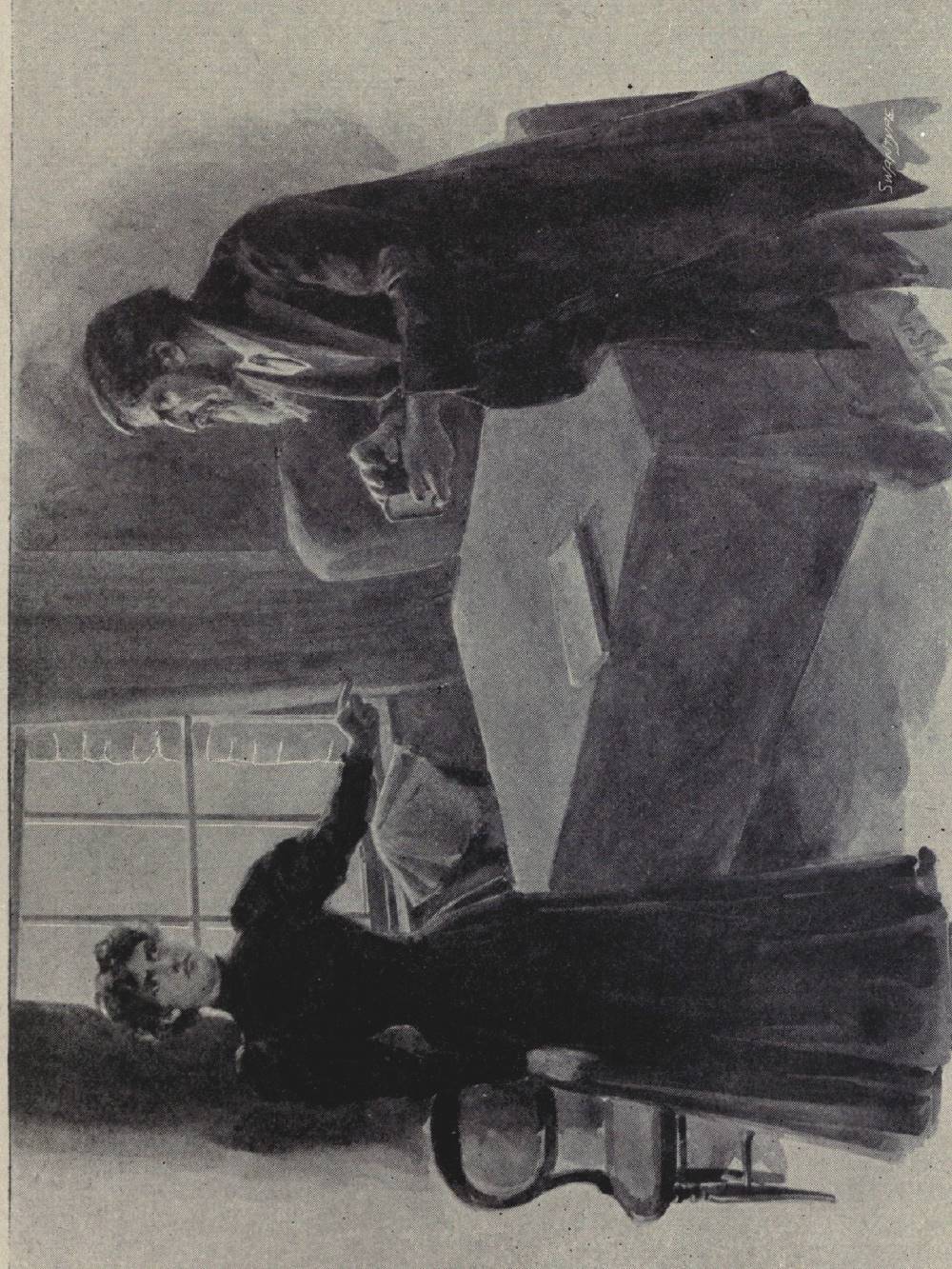

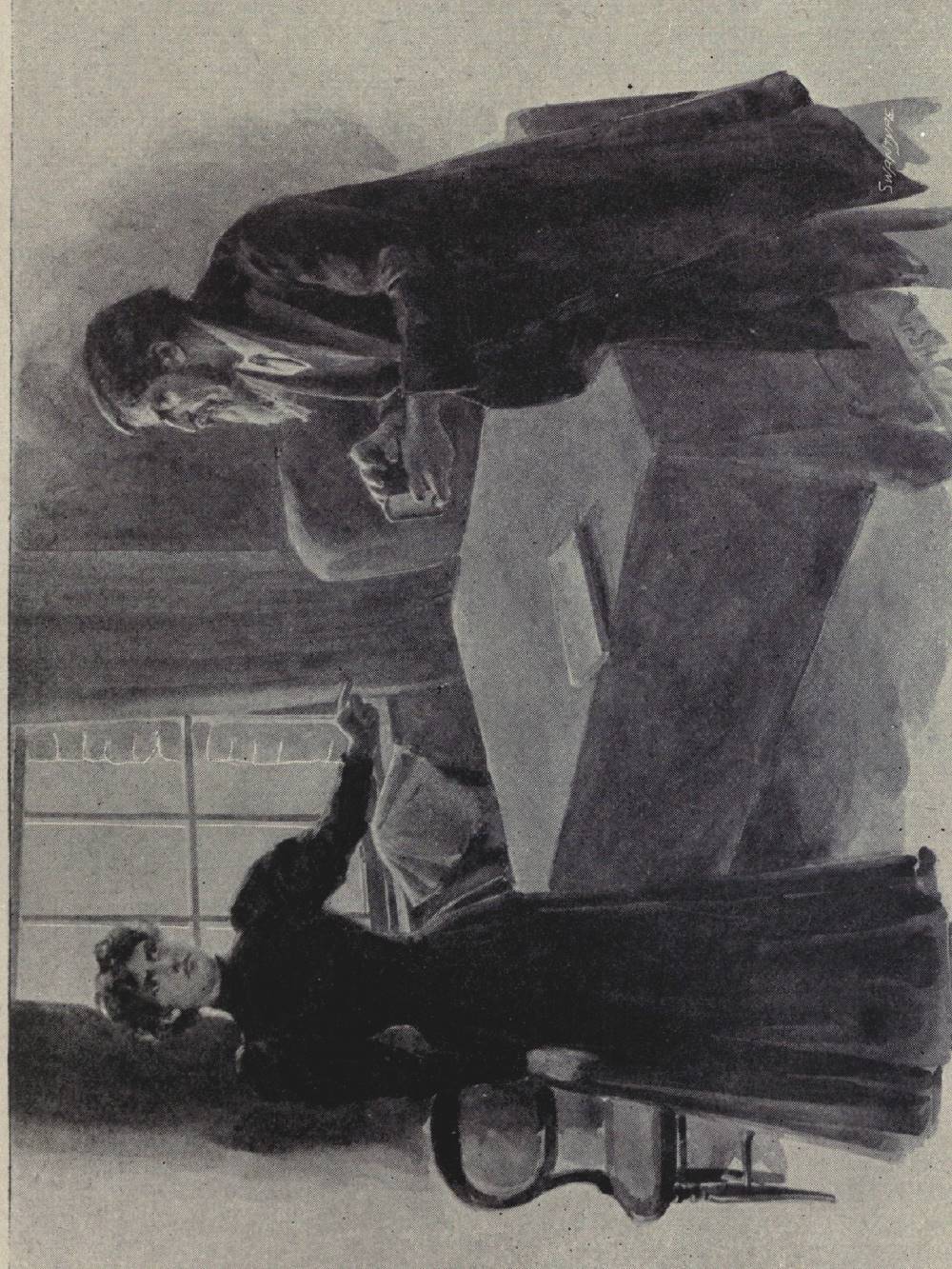

“We spoke of it, Joan, but we did not settle it. We both grew angry, and said and did things which had best be forgotten. You swore that you would never marry me, and I swore that you should live to beg me to marry you, for you drove me mad with your cruel words. We were wrong, both of us; so let’s wipe all that out, for I believe I shall marry you, Joan, and I know that you will never plead with me to do it, nor would I wish it so. Oh! hear me, hear me. You don’t know what I have suffered since I lost you; but I tell you that I have been filled with all the tortures of hell; I have thought of you by day and dreamed of you by night, till I began to believe my brain would burst and that I must go mad, as I shall do if I lose you altogether. At last I heard that you had been ill and got your address, and now once more I come to pray you to take pity on me and to promise to be my wife. If only you will do that, I swear to you I will be the best husband that ever a woman had: yes, I will make myself your slave, and you shall want for nothing which I can give you. I do not ask your love, I do not even ask that you should treat me kindly. Deal with me as you will, be bitter and scornful and trample me in the dirt, and I will be content if only you will let me live where I can see you day by day. This isn’t a new thing with me, Joan it has gone on for years; and now it has come to this, that either I must get the promise of you or go mad. Then do not drive me away, but have mercy as you hope for mercy. Pity me and consent.” And with an inarticulate sound that was half a sob and half a groan, he flung himself upon his knees and, clasping his hands, looked up at her with a rapt face like that of a man lost in earnest prayer.

Joan listened, and as she listened a new and terrible idea crept into her mind. Here, if she chose to take it if she could bring herself to take it was an easy path out of her difficulty: here was that which would effectually cure Henry of any desire to ruin himself by marrying her, and would put her beyond the reach of temptation. The thought made her faint and sick, but still she entertained it, so desperate was the case between her love and what she conceived to be her duty. If it could be done with certain safeguards and reservations why should it not be done? This man was in a humour to consent to anything; it was but a question of the sacrifice of her miserable self, whereby, so they said and so she believed, she would save her lover. In a minute she had made up her mind: at least she would sound the man and put the matter to proof.

“Do not kneel to me,” she said, breaking the silence; “you do not know what sort of woman it is to whom you are grovelling. Get up, and now listen. I love another man; and if I love another man, what do you think that my feelings are to you?”

“I think that you hate me, but I do not mind that,—in time you would come to care for me.”

“I doubt it, Mr. Rock; I cannot change my heart so easily. Do you know what terms I stand on with this man?”

“If you mean Sir Henry Graves, I have heard plenty of all that, and I am ready to forgive you.”

“You are very generous, Mr. Rock, but perhaps I had better explain a little. I think it probable that, unless I change my mind, within a week I shall be married to Sir Henry Graves.”

“Oh! my God!” he groaned; “I never thought that he would marry you.”

“Well, as it happens he will—that is, if I consent. And now do you know why?”

He shook his head.

“Then I will tell you, so that you may understand exactly about the woman whom you wish to make your wife. Do not think that I am putting myself in your power, for in the first place, if you use my words against me I shall deny them, and in the second I shall be married to Sir Henry and able to defy you. This is the reason, Mr. Rock:” and she bent forward and told him all in a few words, speaking in a low, clear voice.

Samuel’s face turned livid as he heard.

“The villain!” he muttered. “Oh! I should like to kill him. The villain—the villain!”

“Don’t talk in that kind of way, Mr. Rock, or, if you wish to do so, leave me. Why should you call him a villain, seeing that he loves me as I love him, and is ready to marry me to-morrow? Are you prepared to do as much now? Stop before you answer: you have not heard all the terms upon which, even if you should still wish it, I might possibly consent to become your wife, or my reason for even considering the matter, First as to the reason; it would be that I might protect Sir Henry Graves from the results of his own good feeling, for it cannot be to his advantage to burden his life with me, and unless I take some such step, or die, I shall probably marry him. Now as to the condition upon which I might consent to marry anybody else, you, for instance, Mr. Rock: it is that I should be left alone to live here or wherever I might select for a year from the present date, unless of my own free will I chose to shorten the time. Do you think that you, or any other man, Mr. Rock, could consent to take a woman upon such terms?”

“What would happen at the end of the year?” he asked.

“At the end of the year,” she answered deliberately, “if I still lived, I should be prepared to become the faithful wife of that man, provided, of course, that he did not attempt to violate the agreement in any particular. If he chose to do so, I should consider the bargain at an end, and he would never see me again.”

“You want to drive a hard trade, Joan.”

“Yes, Mr. Rock a very hard trade. But then, you see, the circumstances are peculiar.”

“It’s too much: I can’t see my way to it, Joan!” he exclaimed passionately.

“I am very glad to hear that, Mr. Rock,” she answered, with evident relief; “and I think that you are quite right. Good-bye.”

Samuel picked up his hat, and rose as though to go.

“Shall you marry him?” he said hoarsely.

“I do not see that I am bound to answer that question, but it is probable, for my own sake I hope so.”

He took a step towards the door, then turned suddenly and dashed his hat down upon the carpet.

“I can’t let you go to him,” he said, with an oath; “I’ll take you upon your own terms, if you’ll give me no better ones.”

“Yes, Mr. Rock: but how am I to know that you will keep those terms?”

“I’ll swear it, but if I swear, when will you marry me?”

“Whenever you like, Mr. Rock. There’s a Bible on the table: if you are in earnest, take it and swear, for then I know you will be afraid to break your oath.”

Samuel picked up the book, and swore thus at her dictation: “I swear that for a year from the date of my marrying you, Joan Haste, I will not attempt to see you, but will leave you to go your own way without interfering with you by word or deed, upon the condition that you have nothing to do with Sir Henry Graves” (this sentence was Samuel’s own), “and that at the end of the year you come to me, to be my faithful wife.” And, kissing the book, he threw it down upon the table, adding, “And may God blast me if I break this oath! Do you believe me now, Joan?”

“On second thoughts I am not sure that I do,” she answered, with a contemptuous smile, “for I think that the man who can take that vow would also break it. But if you do break it, remember what I tell you, that you will see no more of me. After all, this is a free country, Mr. Rock, and even though I become your wife in name, you cannot force me to live with you. There is one more thing: I will not be married to you in a church, I will be married before a registrar, if at all.”

“I suppose that you must have your own way about that too, Joan; though it seems an unholy thing not to ask Heaven’s blessing on us.”

“There is likely to be little enough blessing about the business,” she answered; then added, touched by compunction: “You had best leave it alone, Mr. Rock; it is wicked and wrong from beginning to end, and you know that I don’t love you, nor ever shall, and the reasons why I consent to take you. Be wise and have done with me, and find some other woman who has no such history who will care for you and make you a good wife.”

‘Samuel picked up the book, and swore… at her dictation.’

“No, Joan; you have promised to do that much when the time comes, and I believe you. No other woman could make up to me for the loss of you, not if she were an angel.”

“So be it, then,” she answered; “but do not blame me if you are unhappy afterwards, for I have warned you, and however much I may try to do my duty, it can’t make up to a man for the want of love. And now, when is it to be?”

“You said whenever I liked, Joan, and I say the sooner we are married the sooner the year of waiting will be over. If it can be done, to-morrow or the next day, as I think for you have been living a long while in this parish I will go and make arrangements and come to tell you.”

“Don’t do that, Mr. Rock, as I can’t talk any more to-day. Send me a telegram. And now good-bye: I want to rest.”

He waited for her to offer him her hand, but she did not do so. Then he turned and went, walking so softly that until she heard the front door close Mrs. Bird was unaware that he had left the room above. Throwing down her work she ran upstairs, for her curiosity would not allow her to delay. Joan was seated on the sofa staring out of the window, with wide-opened eyes and a face so set that it might have been cut in stone.

“Well, my dear,” said the little woman, “so you have seen Sir Henry, and I hope that you have arranged everything satisfactorily?”

Joan heard and smiled; even then it struck her as ludicrous that Mrs. Bird could possibly mistake Samuel Rock for Sir Henry Graves. But she did not attempt to undeceive her, since to do so would have involved long explanations, on which at the moment she had neither the wish nor the strength to enter; moreover, she was sure that Mrs. Bird would disapprove of this strange contract and oppose it with all her force. Even then, however, she could not help reflecting how oddly things had fallen out. It was as though some superior power were smoothing away every difficulty, and, to fulfil secret motives of its own, was pushing her into this hideous and shameful union. For instance, though she had never considered it, had not Mrs. Bird fatuously taken it for granted that her visitor must be Sir Henry and no other man, it was probable that she would have found means to prevent him from seeing her, or, failing that, she would have put a stop upon the project by communicating with Henry. For a moment Joan was tempted to tell her the truth and let her do what she would, in the hope that she might save her from herself. But she resisted the desire, and answered simply,—

“Yes; I shall probably be married to-morrow or the next day.”

“To-morrow!” ejaculated Mrs. Bird, holding up her hands. “Why, you haven’t even got a dress ready.”

“I can do without that,” she replied, “especially as the ceremony is to be before a registrar.”

“Before a registrar, Joan! Why, if I did such a thing I should never feel half married; besides, it’s wicked.”

“Perhaps,” said Joan, smiling again; “but it is the only fashion in which it can be arranged, and it will serve our turn. By the way, shall you mind if I come back to live here afterwards?”

“What, with your husband? There would not be room for two of you; besides, a baronet could never put up with a place like this.”

“No, without him. We are going to keep separate for a year.”

“Good heavens!” exclaimed Mrs. Bird, “what an extraordinary arrangement!”

“There are difficulties, Mrs. Bird, and it is the only one that we could come to. I suppose that I can stay on?”

“Oh! yes, if you like; but really I do not understand.”

“I can’t explain just at present, dear,” said Joan gently. “I am too tired; you will know all about it soon.”

“Well,” thought Mrs. Bird, as she left the room, “somehow I don’t like that baronet so much as I did. It is all so odd and secret. I hope that he doesn’t mean to deceive Joan with a false marriage and then to desert her. I have heard of people of rank doing such things. But if he tries it on he will have to reckon with me.”

That afternoon Joan received the following telegram: “All arranged. Will call for you at two the day after to-morrow. Samuel.”