CHAPTER XXXVII.

THE TRUTH, THE WHOLE TRUTH.

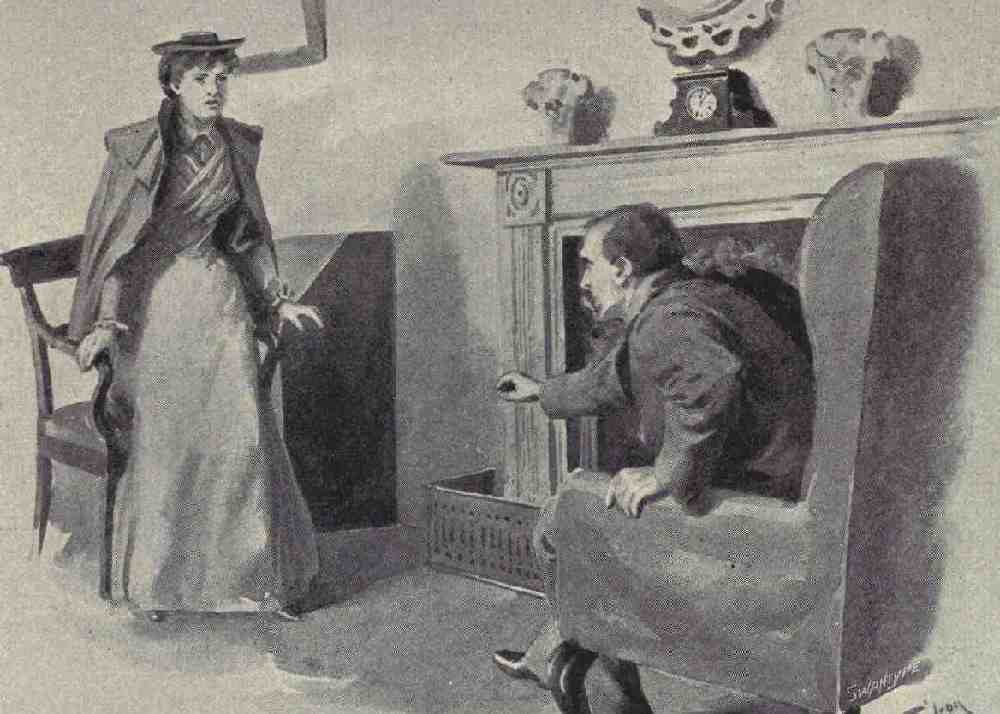

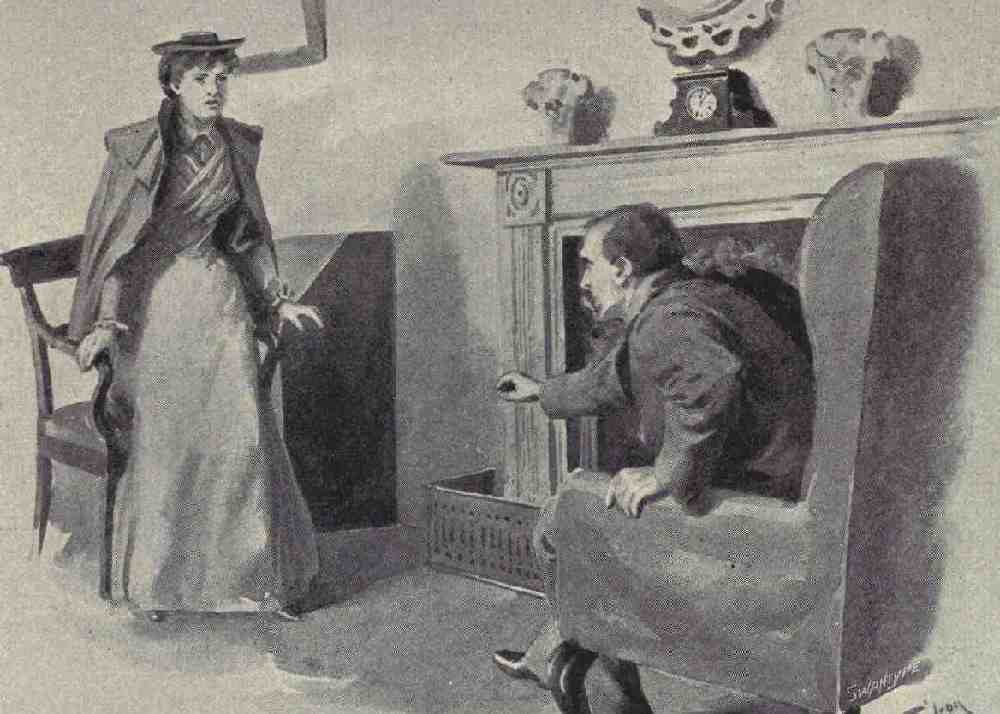

“Your daughter!” she said, rising in her astonishment, “you must be mad! If I were your daughter, could you have lied to me as you did, and treated me as you have done?”

‘Your daughter!’

“I pray you to listen before you judge, and at present spare your reproaches, for believe me, Joan, I am not fit to bear them. Remember that I need have told you nothing of this; the secret might have been buried in my grave—”

“As it would have been, sir, had you not feared to die with such falsehood on your soul.”

He made an imploring gesture with his hand, and she ceased.

“Joan,” he went on, “I will tell you the whole truth. You are not only my child, you are also legitimate.”

“And Miss Levinger—Lady Graves, I mean—is she legitimate too?”

“No, Joan.”

She heard, and bit her lip till the blood ran, but even so she could not keep silence.

“Oh!” she cried, “I wonder if you will ever understand what you have done in hiding this from me. Do you know that you have ruined my life?”

“I pray that you may be mistaken, Joan. Heaven is my witness that I have tried to act for the best. Listen: many years ago, when I was still a youngish man, it was my fate to meet and to fall in love with your mother, Jane Lacon. Like you, she was beautiful, but unlike you she was hot-tempered, violently jealous, and, when she was angered, rough of speech. Such as she was, however, she obtained a complete empire over my mind, for I was headstrong and passionate; indeed, so entirely did I fall into her power that in the end I consented to marry her. This, however, I did not dare to do here, for in those days I was poor and struggling, and it would have ruined me. Separately, and without a word being said to any one, we went to London, and there were secretly married in an obscure parish in the East End. In proof of my words here is a copy of the certificate,”—and, taking a paper from a despatch-box that stood on the table beside him, he handed it to Joan, then went on:—

“As you may guess, a marriage thus entered into between two people so dissimilar in tastes, habits and education did not prove successful. For a month or so we were happy, then quarrels began. I established her in lodgings in London, and, while ostensibly carrying on my business as a land agent here, visited her from time to time. With this, however, she was not satisfied, for she desired to be acknowledged openly as my wife and to return with me to Bradmouth. I refused to comply indeed, I dared not do so whereupon she reviled me with ever-increasing bitterness. Moreover she became furiously jealous, and extravagant beyond the limit of my means. At length matters reached a climax, for a chance sight that she caught of me driving in a carriage with another woman, provoked so dreadful an outburst that in my rage and despair I told her a falsehood. I told her, Joan, that she was not really my wife, and had no claim upon me, seeing that I had married her under a false name. This in itself was true, for my own name is not Levinger; but it is not true that the marriage was thereby invalidated, since neither she nor those among whom I had lived for several years knew me by any other. When your mother heard this she replied only that such conduct was just what she should have expected from me; and that night I returned to Bradmouth, having first given her a considerable sum of money, for I did not think that I should see her again for some time. Two days afterwards I received a letter from her,—here it is,” and he read it:—

“‘GEORGE,

“‘Though I may be what you call me, a common woman and a jealous scold, at least I have too much pride to go on living with a scoundrel who has deceived me by a sham marriage. If I were as bad as you think, I might have the law of you, but I won’t do that, especially as I dare say that we shall be best apart. Now I am going straight away where you will never find me, so you need not trouble to look, even if you care to. I haven’t told you yet that I expect to have a child. If it comes to anything, I will let you know about it; if not, you may be sure that it is dead, or that I am. Good-bye, George: for a week or two we were happy, and though you hate me, I still love you in my own way; but I will never live with you again, so don’t trouble your head any more about me.

‘Yours,

‘JANE——?

“‘P.S. Not knowing what my name is, I can’t sign it.’

“When I received this letter I went to London and tried to trace your mother, but could hear nothing of her. Some eight or nine months passed by, and one day a letter came addressed to me, written by a woman in New York—I have it here if you wish to see it—enclosing what purports to be a properly attested American certificate of the death of Jane Lacon, of Bradmouth in England. The letter says that Jane Lacon, who passed herself off as a widow, and was employed as a housekeeper in an hotel in New York, died in childbirth with her infant in the house of the writer, who, by her request, forwarded the certificate of death, together with her marriage ring and her love.

“I grieved for your mother, Joan; but I made no further inquiries, as I should have done, for I did not doubt the story, and in those days it was not easy to follow up such a matter on the other side of the Atlantic.

“A year went by and I married again, my second wife being Emma Johnson, the daughter of old Johnson, who owned a fleet of fishing boats and a great deal of other property, and lived at the Red House in Bradmouth. Some months after our marriage he died, and we came to live at Monk’s Lodge, which we inherited from him with the rest of his fortune. A while passed, and Emma was born; and it was when her mother was still confined to her room that one evening, as I was walking in front of the house after dinner, I saw a woman coming towards me carrying a fifteen-months’ child in her arms. There was something in this woman’s figure and gait that was familiar to me, and I stood still to watch her pass. She did not pass, however; she came straight up to me and said:—

“‘How are you, George? You ought to know me again, though you won’t know your baby.’

“It was your mother, and, Joan, you were that baby.

“‘I thought that you were dead, Jane,’ I said, so soon as I could speak.

“‘That’s just what I meant you to think, George,’ she answered, ‘for at that time I had a very good chance of marrying out there in New York, and didn’t want you poking about after me, even though you weren’t my lawful husband. Also I couldn’t bear to part with the baby; though it’s yours sure enough, and I’ve been careful to bring its birth papers with me to show you that it is not a fraud; and here they are, made out in your name and mine, or at least in the name that you pretended to marry me under.’ And she gave me this certificate, which, Joan, I now pass on to you.

“‘The fact of the matter is,’ she went on, ‘that when it came to the point I found that I couldn’t marry the other man after all, for in my heart I hated the sight of him and was always thinking of you. So I threw him up and tried to get over it, for I was doing uncommonly well out there, running a lodging-house of my own. But it wasn’t any use: I just thought of you all day and dreamed of you all night, and the end of it was that I sold up the concern and started home. And now if you will marry me respectable so much the better, and if you won’t—well, I must put up with it, and sha’n’t show you any more temper, for I’ve tried to get along without you and I can’t, that’s the fact. You seem to be pretty flourishing, anyway; somebody in the train told me that you had come into a lot of money and bought Monk’s Lodge, so I walked here straight, I was in such a hurry to see you. Why, what’s the matter with you, George? You look like a ghost. Come, give me a kiss and take me into the house. I’ll clear out by-and-by if you wish it.’

“These, Joan, were your mother’s exact words, as she stood there in the moonlight near the roadway, holding you in her arms. I have not forgotten a syllable of them.

“When she finished I was forced to speak. ‘I can’t take you in there,’ I said, because I am married and it is my wife’s house.’ She turned ghastly white, and had I not caught her I think that she would have fallen.

“‘O My God!’ she said, ‘I never thought of this. Well, George, you won’t cast me off for all that, will you? I was your wife before she was, and this is your daughter.’

“Then, Joan, though it nearly choked me, I lied to her again, for what else was I to do? ‘You never were my wife,’ I said, ‘and I’ve got another daughter now. Also all this is your own fault, for had I known that you were alive, I would not have married. You have yourself to thank, Jane, and no one else. Why did you send me that false certificate?’

“‘I suppose so,’ she answered heavily. ‘Well, I’d best be off; but you needn’t have been so ready to believe things. Will you look after the child if anything happens to me, George? She’s a pretty babe, and I’ve taught her to say Daddy to nothing.’

“I told your mother not to talk in that strain, and asked her where she was going to spend the night, saying that I would see her again on the morrow. She answered, at her sister’s, Mrs. Gillingwater, and held you up for me to kiss. Then she walked away, and that was the last time that I saw her alive.

“It seems that she went to the Crown and Mitre, and made herself known to your aunt, telling her that she had been abroad to America, where she had come to trouble, but that she had money, in proof of which she gave her notes for fifty pounds to put into a safe place. Also she said that I was the agent for people who knew about her in the States, and was paid to look after her child. Then she ate some supper, and saying that she would like to take a walk and look at the old place, as she might have to go up to London on the morrow, she went out. Next morning she was found dead beneath the cliff, though how she came there, there was nothing to show.

“That, Joan, is the story of your mother’s life and death.”

“You mean the story of my mother’s life and murder,” she answered. “Had you not told her that lie she would never have committed suicide.”

“You are hard upon me, Joan. She was more to blame than I was. Moreover, I do not believe that she killed herself. It was not like her to have done so. At the place where she fell over the cliff there stood a paling, of which the top rail, that was quite rotten, was found to have been broken. I think that my poor wife, being very unhappy, walked along the cliff and leaned upon this rail wondering what she should do, when suddenly it broke and she was killed, for I am sure that she had no idea of making away with herself.

“After her death Mrs. Gillingwater came to me and repeated the tale which her sister had told her, as to my having been appointed agent to some person unknown in America. Here was a way out of my trouble, and I took it, saying that what she had heard was true. This was the greatest of my sins; but the temptation was too strong for me, for had the truth come out I should have been utterly destroyed, my wife would have been no wife, her child would have been a bastard, I should have been liable to a prosecution for bigamy, and, worst of all, my daughter’s heritage might possibly have passed from her to you.”

“To me?” said Joan.

“Yes, to you; for under my father-in-law’s will all his property is strictly settled first upon his daughter, my late wife, with a life interest to myself, and then upon my lawful issue. You are my only lawful issue, Joan; and it would seem, therefore, that you are legally entitled to your half-sister’s possessions, though of course, did you take them, it would be an act of robbery, seeing that the man who bequeathed them certainly desired to endow his own descendants and no one else, the difficulty arising from the fact of my marriage with his daughter being an illegal one. I have taken the opinions of four leading lawyers upon the case, giving false names to the parties concerned. Of these, two have advised that you would be entitled to the property, since the law is always strained against illegitimate issue, and two that equity would intervene and declare that her grandfather’s inheritance must come to Emma, as he doubtless intended, although there was an accidental irregularity in the marriage of the mother.

“I have told you all this, Joan, as I am telling you everything, because I wish to keep nothing back; but I trust that your generosity and sense of right will never allow you to raise the question, for this money belongs to Emma and to her alone. For you I have done my best out of my savings, and in some few days or weeks you will inherit about four thousand pounds, which will give you a competence independent of your husband.”

“You need not be afraid, sir,” answered Joan contemptuously; “I would rather cut my fingers off than touch a farthing of the money to which I have no right at all. I don’t even know that I will accept your legacy.”

“I hope that you will do so, Joan, for it will put you in a position of complete independence, will provide for your children, and will enable you to live apart from your husband, should you by any chance fail to get on with him. And now I have told you the whole truth, and it only remains for me to most humbly beg your forgiveness. I have done my best for you, Joan, according to my lights; for, as I could not acknowledge you, I thought it would be well that you should be brought up in your mother’s class—though here I did not make sufficient allowance for the secret influences of race, seeing that, not withstanding your education, you are in heart and appearance a lady. I might, indeed, have taken you to live with me, as I often longed to do; but I feared lest such an act should expose me to suspicion, suspicion should lead to inquiry, and inquiry to my ruin and to that of my daughter Emma. Doubtless it would have been better, as well as more honest, if I had faced the matter out; but at the time I could not find the courage, and the opportunity went by. My early life had not been altogether creditable, and I could not bear the thought of once more becoming the object of scandal and of disgrace, or of imperilling the fortune and position to which after so many struggles I had at length attained. That, Joan, is my true story; and now again I say that I hope to hear you forgive me before I die, and promise that you will not, unless it is absolutely necessary, reveal these facts to your half-sister, Lady Graves, for if you do I verily believe that it will break her heart. The dread lest she should learn this history has haunted me for years, and caused me to strain every nerve to secure her marriage with a man of position and honourable name, so that, even should it be discovered that she had none, she might find a refuge in her disgrace. Thank Heaven that I, who have failed in so many things, have at least succeeded in this, so that, come what may when I am dead, she is provided for and safe.”

“I suppose, sir, that Sir Henry Graves knows all this?”

“Knows it! Of course not. Had he known it I doubt if he would have married her.”

“Possibly not. He might even have married somebody else,” Joan answered. “It seems, then, that you palmed off Miss Emma upon him under a false description.”

“I did,” he said, with a groan. “It was wrong, like the rest; but one evil leads to another.”

“Yes, sir, one evil leads to another, as I shall show you presently. You ask me to forgive you, and you talk about the breaking of Lady Graves’s heart. Perhaps you do not know that mine is already broken through you, or to what a fate you have given me over. I will tell you. Your daughter’s husband, Sir Henry Graves, and I loved each other, and I have borne his child. He wished to marry me, though, believing myself to be what you have taught me to believe, I was against it from the first. When he learned my state he insisted upon marrying me, like the honourable man that he is, and told his mother of his intention. She came to me in London and pleaded with me, almost on her knees, that I should ward off this disgrace from her family, and preserve her son from taking a step which would ruin him. I was moved by her entreaties, and I felt the truth of what she said; but I knew well that, should he come to marry me, as within a few days he was to do, for our child’s and our love’s sake, if not for my own, I could never find the strength to deny him.

“What was I to do? I was too ill to run away, and he would have hunted me out. Therefore it came to this, that I must choose between suicide—which was both wicked and impossible, for I could not murder another as well as myself—and the still more dreadful step that at length I took. You know the man Samuel Rock, my husband, and perhaps you know also that for a long while he has persecuted me with his passion, although again and again I have told him that he was hateful to me. While I was ill he obtained my address in London—I believe that he bought it from my aunt, Mrs. Gillingwater, the woman in whose charge you were satisfied to leave me—and two days after I had seen Lady Graves, he came to visit me, gaining admission by passing himself off as Sir Henry to my landlady, Mrs. Bird.

“You can guess the rest. To put myself out of temptation, and to save the man I loved from being disgraced and contaminated by me, I married the man I hated—a man so base that, even when I had told him all, and bargained that I should live apart from him for many months, he was yet content to take me. I did more than this even: I wrote in such a fashion to Sir Henry as I knew must shock and revolt him; and then I married, leaving him to believe that I had thrown him over because the husband whom I had chosen was richer than himself. Perhaps you cannot guess why I should thus have dishonoured both of us, and subjected myself to the horrible shame of making myself vile in Sir Henry’s eyes. This was the reason: had I not done so, had he once suspected the true motives of my sacrifice, the plot would have failed. I should have sold myself for nothing, for then he would never have married Emma Levinger. And now, that my cup may be full, my child is dead, and to-morrow I must give myself over to my husband according to the terms of my bond. This, sir, is the fruit of all your falsehoods; and I say, Ask God to forgive you, but not the poor girl—your own daughter—whom you have robbed of honour and happiness, and handed over to misery and shame.”

Thus Joan spoke to him, in a quiet, an almost mechanical voice indeed, but standing on her feet above the dying man, and with eyes and gestures that betrayed her absorbing indignation. When she had finished, her father, who was crouched in the chair before her, let fall his hands, wherewith he had hidden his face, and she saw that he was gasping for breath and that his lips were blue.

“‘The way of transgressors is hard,’ as we both have learned,” he muttered, with a deathly smile, “and I deserve it all. I am sorry for you, Joan, but I cannot help you. If it consoles you, you may remember that, whereas your sorrows and shame are but temporal, mine, as I fear will be eternal. And now, since you refuse to forgive me, farewell; for I can talk no more, and must make ready, as best I can, to take my evil doings hence before another, and, I trust, a more merciful Judge.”

Joan turned to leave the room, but ere she reached the door the rage died out of her heart and pity entered it.

“I forgive you, father,” she said, “for it is Heaven’s will that these things should have happened, and by my own sin I have brought the worst of them upon me. I forgive you, as I hope to be forgiven. But oh! I pray that my time here may be short.”

“God bless you for those words, Joan!” he murmured.

Then she was gone.