CHAPTER XXXIX.

HUSBAND AND WIFE.

When Joan parted from Henry she walked quickly to Monk’s Vale station to catch the train. Arriving just in time, she bought a third-class ticket to Bradmouth, and got into an empty carriage. Already they were starting, when the door opened, and a man entered the compartment. At first she did not look at him, so intent was she upon her own thoughts, till some curious influence caused her to raise her eyes, and she saw that the man was her husband, Samuel Rock.

She gazed at him astonished, although it was not wonderful that she should chance to meet a person within a few miles of his own home; but she said nothing.

“How do you do, Joan?” Samuel began, and as he spoke, she noticed that his eyes were bloodshot and wild, and his face and hands twitched: “I thought I couldn’t be mistook when I saw you on the platform.”

“Have you been following me, then?” she asked.

“Well, in a way I have. You see it came about thus: this morning I find that young villain, Willie Hood, driving his donkeys off my foreshore pastures, and we had words, I threatening to pull him, and he giving me his sauce.

“Presently he says, ‘You’d be better employed looking after your wife than grudging my dickies a bellyful of sea thistles; for, as we all know, you are a very affectionate husband, and would like to see her down here after she’s been travelling so long for the benefit of her health.’ Then, of course, I ask him what he may chance to mean; for though I have your letter in my pocket saying that you were coming home shortly, I didn’t expect to have the pleasure of seeing you to-day, Joan; and he tells me that he met you last night bound for Monk’s Vale. So you see to Monk’s Vale I come, and there I find you, though what you may happen to be doing, naturally I can’t say.”

“I have been to see Mr. Levinger,” she answered; “he is very ill, and telegraphed for me yesterday.”

“Did he now! Of course that explains everything; though why he should want to see you it isn’t for me to guess. And now where might you be going, Joan? Is it ‘home, sweet home’ for you?”

“I propose to go to Moor Farm, if you find it convenient.”

“Oh, indeed! Well, then, that’s all right, and you’ll be heartily welcome. The place has been done up tidy for you, Joan, by the same man that has been working at Rosham to make ready for the bride. She’s come home to-day too, and it ain’t often in these parts that we have two brides home-coming together. It makes one wonder which of the husbands is the happier man. Well, here we are at Bradmouth, so if you’ll come along to the Crown and Mitre I’ll get my cart and we’ll drive together. There are new folks there now. Your aunt’s in jail, and your uncle is in the workhouse; and both well suited, say I, though p‘raps you will think them a loss.”

To all this talk, and much more like it, Joan made little or no answer. She was not in a condition to observe people or things closely, nevertheless it struck her that there was something very strange about Samuel’s manner. It occurred to her even that he must have been drinking, so wild were his looks and so palpable his efforts to keep his words and gestures under some sort of control.

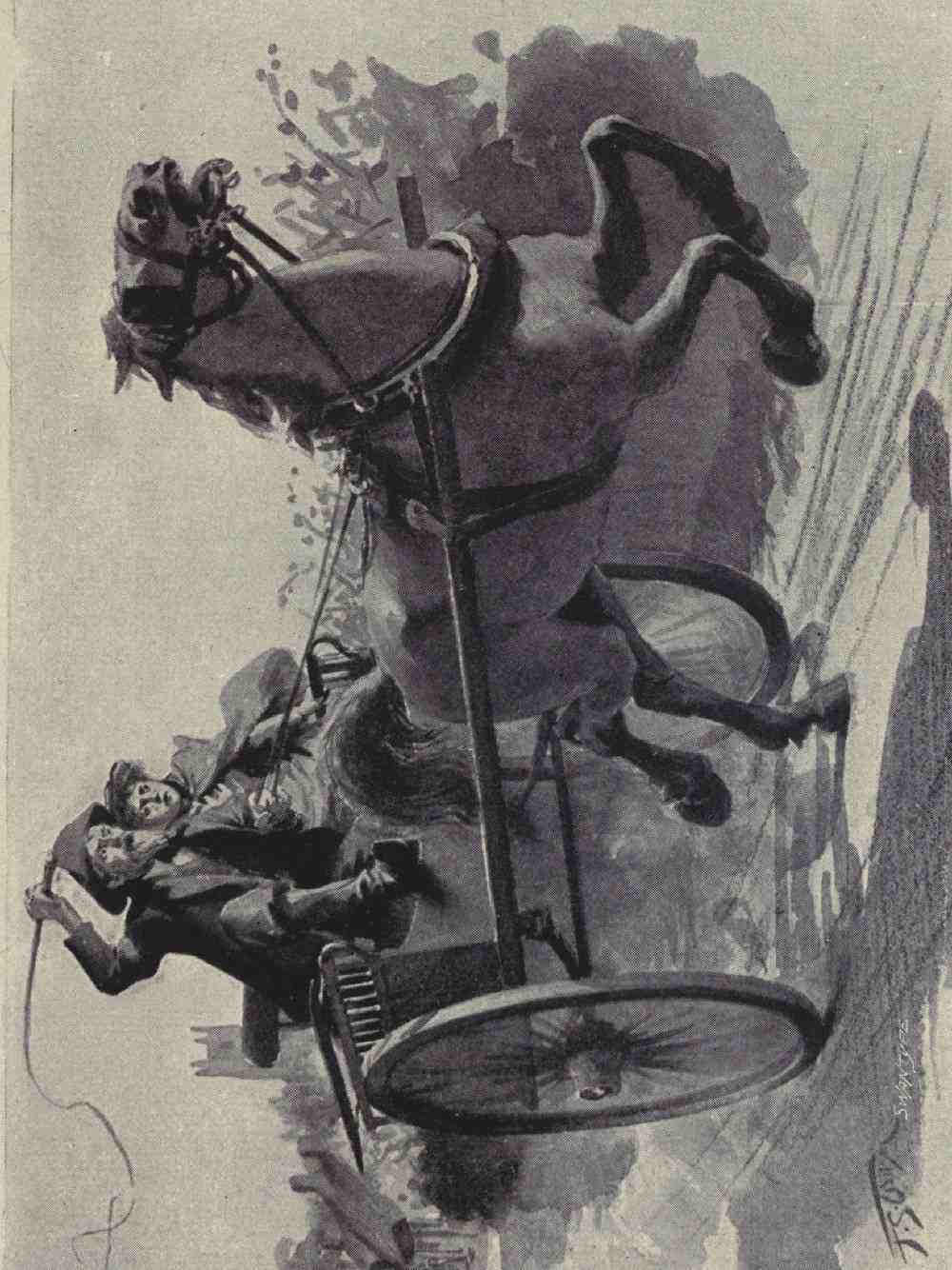

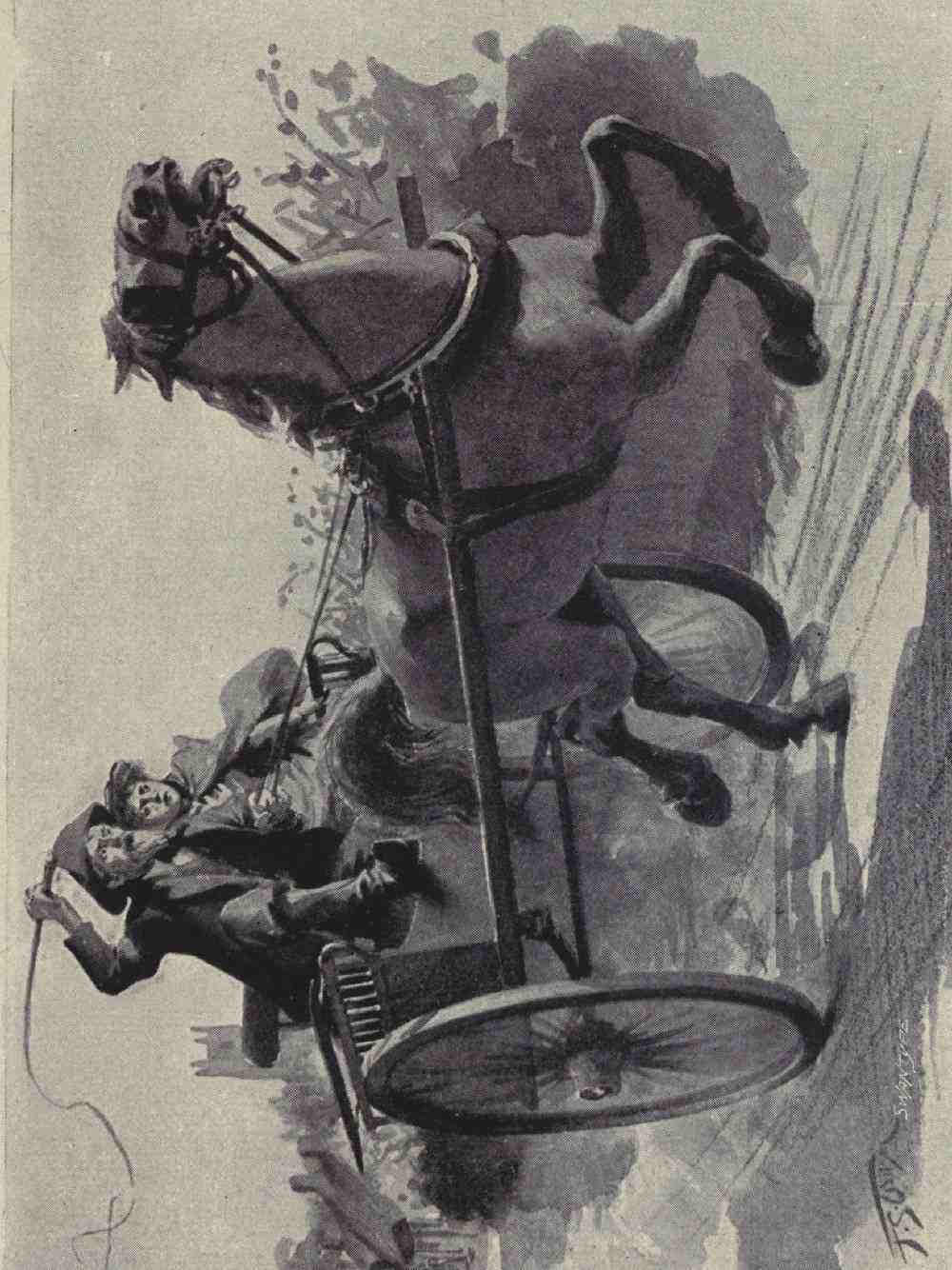

Presently they were seated in the cart and had started for Moor Farm. The horse was a young and powerful animal, but Samuel drove it quietly enough till they were clear of the village. Then he commenced to shout at it and to lash it with his whip, till the terrified beast broke into a gallop and they were tearing along the road at a racing pace.

“We can’t get home too fast, can we, darling?” he yelled into her ear, “and the nag knows it. Come on, Sir Henry,—come on! You know that a pretty woman likes to go the pace, don’t you?” and again he brought down his heavy whip across the horse’s flanks.

Joan clung to the rail of the cart, clenched her teeth and said nothing. Luckily the last half-mile of the road ran up a steep incline, and, notwithstanding Rock’s blows and urgings, the horse, being grass-fed, became blown, and was forced to moderate its pace. Opposite the door of the house Rock pulled it up so suddenly that Joan was almost thrown on to her head; but, recovering her balance, she descended from the cart; which her husband gave into the charge of a labourer.

“Here’s your missus come home at last, John,” he said, with an idiotic chuckle. “Look at her: she’s a sight for sore eyes, isn’t she?”

“Glad to see her, I’m sure,” answered the man. “But if you drive that there horse so you’ll break his wind, that’s all, or he’ll break your neck, master.”

“Ah! John, but you see your missus likes to go fast. We’ve been too slow up at Moor Farm, but all that’s going to be changed now.”

As he spoke two great dogs rushed round the corner of the house baying, and one of them, seeing that Joan was a stranger, leapt at her and tore the sleeve of her dress. She cried out in fear, and the man, John, running from the head of the horse, beat the dogs back.

“Ah! you would, Towser, would you?” said Rock. “You wait a moment, and I’ll teach you that no one has a right to touch a lady except her husband,” and he ran into the house.

‘Come on, Sir Henry—come on!’

“Don’t go, pray,” said Joan to the man; “I am frightened,” —and she shrank to his side for protection, for the dogs were still walking round her growling, their hair standing up upon their backs.

By way of answer John tapped his forehead significantly and whispered, “You look out for yourself, missus; he’s going as his grandfather did. He’s allus been queer, but I never did see him like this before.”

Just then Rock reappeared from the house, carrying his double-barrelled gun in his hand.

“Towser, old boy! come here, Towser!” he said, addressing the dog in a horrible voice of pretended affection, that, however, did not deceive it, for it stood still, eyeing him suspiciously.

“Surely,” Joan gasped, “you are not going——”

The words were scarcely out of her mouth when there was a report, and the unfortunate Towser rolled over on to his side dying, with a charge of No. 4 shot in his breast. The horse, frightened by the noise, started off, John hanging to the reins.

“There, Towser, good dog,” said Rock, with a brutal laugh, “that’s how I treat them that try to interfere with my wife. Now come in, darling, and see your pretty home.”

Joan, who had hidden her eyes that she might not witness the dying struggles of the wretched dog, let fall her hand, and looked round wildly for help. Seeing none, she took a few steps forward with the idea of flying from this fiend.

“Where are you going, Joan?” he asked suspiciously. “Surely you are never thinking of running away, are you? Because I tell you, you won’t do that; so don’t you try it, my dear. If I’m to be a widower again, it shall be a real one next time.” And he lifted the gun towards her and grinned.

Then, the man John having vanished with the cart, Joan saw that her only chance was to appear unconcerned and watch for an opportunity to escape later.

“Run away!” she said, “what are you thinking of? I only wanted to see if the horse was safe,” and she turned and walked through the deserted garden to the front door of the house, which she entered.

Rock followed her, locking the door behind her as he had done when Mrs. Gillingwater came to visit him, and with much ceremonious politeness ushered her into the sitting-room. This chamber had been re-decorated with a flaring paper, that only served to make it even more incongruous and unfit to be lived in by any sane person than before; and noting its gloom, which by contrast with the brilliant June sunshine without was almost startling, and the devilish faces of carved stone that grinned down upon her from the walls, Joan crossed its threshold with a shiver of fear.

“Here we are at last!” said Samuel. “Welcome to your home, Joan Rock!” And he made a movement as though to embrace her, which she avoided by walking straight past him to the farther side of the table.

“You’ll be wanting something to eat, Joan,” he went on. “There’s plenty in the house if you don’t mind cooking it. You see I haven’t got any servants here at present,” he added apologetically, “as you weren’t expected so soon; and the old woman who comes in to do for me is away sick.”

“Certainly I will cook the food,” Joan answered.

“That’s right, dear—I was afraid that you might be too grand but perhaps you would like to wash your hands first while I light the fire in the kitchen stove. Come here,” and he led the way through the door near the fireplace to the foot of an oaken stair. “There,” he said, “that’s our room, on the right. It’s no use trying any of the others, because they’re all locked up. I shall be just here in the kitchen, so you will see me when you come down.”

Joan went upstairs to the room, which was large and well furnished, though, like that downstairs, badly lighted by one window only, and secured with iron bars, as though the place had been used as a prison at some former time. Clearly it was Samuel’s own room, for his clothes and hats were hung upon some pegs near the door, and other of his possessions were arranged in cupboards and on the shelves.

Almost mechanically she washed her hands and tidied her hair with a brush from her handbag. Then she sat down and tried to think, to find only that her mind had become incapable, so numbed was it by all that she had undergone, and with the terrors mental and bodily of her present position. Nor indeed was much time allowed her for thought, since presently she heard the hateful voice of her husband calling to her that the fire was ready. At first she made no answer, whereon Samuel spoke again from the foot of the stairs, saying,—

“If you won’t come down, dear, I must come up, as I can’t bear to lose sight of you for so long at a time.”

Then Joan descended to the kitchen, where the fire burnt brightly and a beef-steak was placed upon the table ready for cooking. She set to work to fry the meat and to boil the kettle and the potatoes; while Samuel, seated in a chair by the table, followed her every movement with his eyes.

“Now, this is what I call real pleasant and homely,” he said, “and I’ve been looking forward to it for many a month as I sat by myself at night. Not that I want you to be a drudge, Joan—don’t you think it. I’ve got lots of money, and you shall spend it: yes, you shall have your carriage and pair if you like.”

“You are very kind,” she murmured, “but I don’t wish to live above my station. Perhaps you will lay the table and bring me the teapot, as I think that the steak is nearly done.”

He rose to obey with alacrity, but before he left the room Joan saw with a fresh tremor that he was careful to lock the kitchen door and to put the key into his pocket. Evidently he suspected her of a desire to escape.

In a few more minutes the meal was ready, and they were seated tête-à-tête in the parlour.

When he had helped her Joan asked him if she should pour out the tea.

“No, never mind that wash,” he said; “I’ve got something that I have been keeping against this day.” And going to a cupboard he produced glasses and two bottles, one of champagne and the other of brandy. Opening the first, he filled two tumblers with the wine, giving her one of them.

“Now, dear, you shall drink a toast,” he said. “Repeat it after me. ‘Your health, dearest husband, and long may we live together.’”

Having no option but to fall into his humour, or run the risk of worse things, Joan murmured the words, although they almost choked her, and drank the wine—for which she was very thankful, for by now it was past seven o’clock, and she had touched nothing since the morning. Then she made shift to swallow some food, washing it down with sips of champagne. If she ate little, however, her husband ate less, though she noticed with alarm that he did not spare the bottle.

“It isn’t often that I drink wine, Joan,” he said, “for I hold it sinful waste not but what there’ll always be wine for you if you want it. But this is a night to make merry on, seeing that a man isn’t married every day,” and he finished the last of the champagne. “Oh! Joan,” he added, “it’s like a dream to think that you’ve come to me at last. You don’t know how I’ve longed for you all these months; and now you are mine, mine, my own beautiful Joan for those whom God has joined together no man can put asunder, however much they may try. I kept my oath to you faithful, didn’t I, Joan? and now it’s your turn to keep yours to me. You remember what you swore that you would be a true and good wife to me, and that you wouldn’t see nothing of that villain who deceived you. I suppose that you haven’t seen him during all these months, Joan?”

“If you mean Sir Henry Graves,” she answered, “I met him to-day as I walked to Monk’s Vale station.”

“Did you now?” he said, with a curious writhing of the lips: “that’s strange, isn’t it, that you should happen to go to Monk’s Lodge without saying nothing to your husband about it, and that there you should happen to meet him within a few hours of his getting back to England? I suppose you didn’t speak to him, did you?”

“I spoke a few words.”

“Ah! a few words. Well, that was wrong of you, Joan, for it’s against your oath; but I dare say that they were to tell him just to keep clear in future?”

Joan nodded, for she dared not trust herself to speak.

“Well, then, that’s all right, and he’s done with. And now, Joan, as we’ve finished supper, you come here like a good wife, and put your arms round my neck and kiss me, and tell me that you love me, and that you hate that man, and are glad that the brat is dead.”

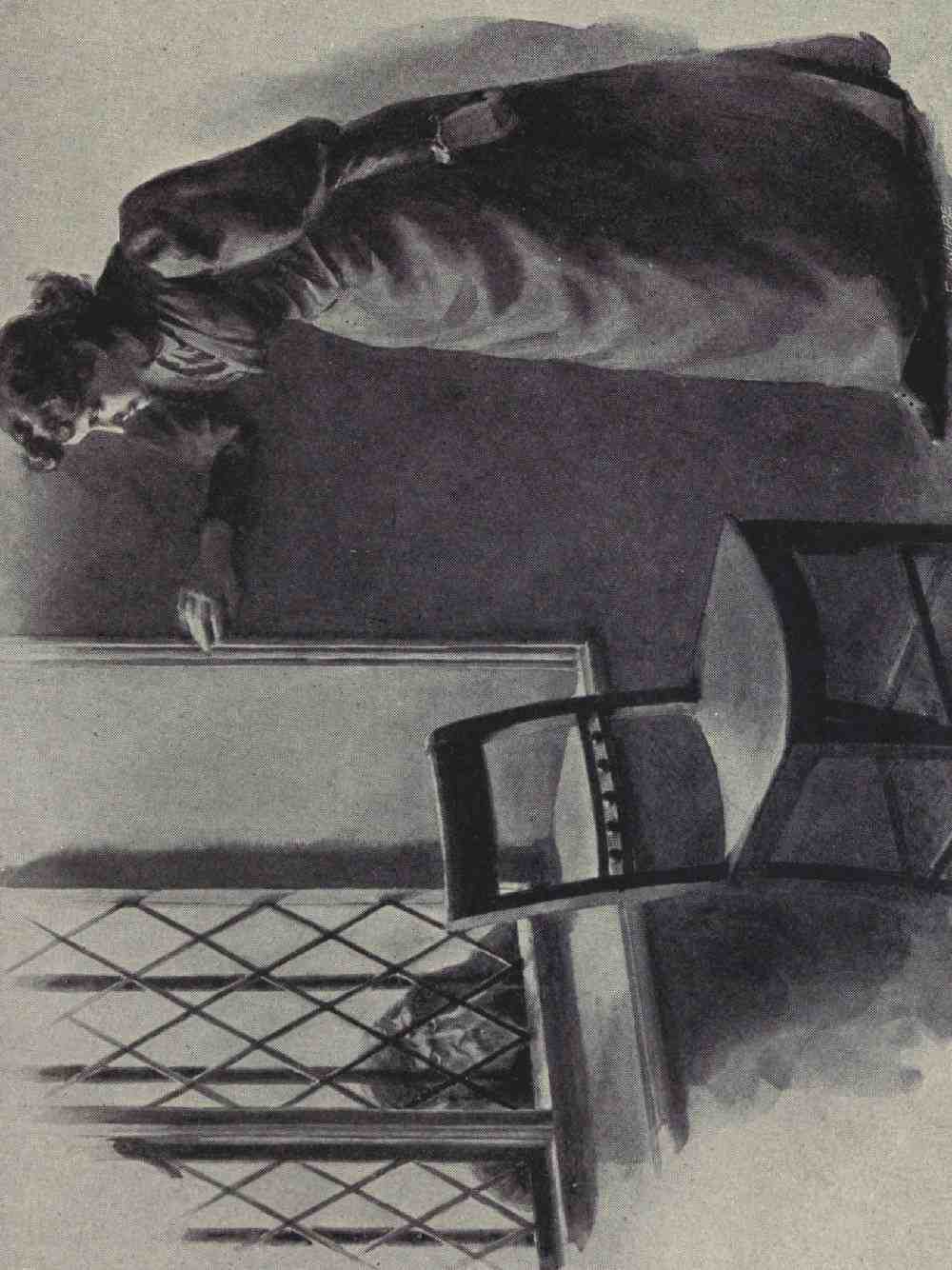

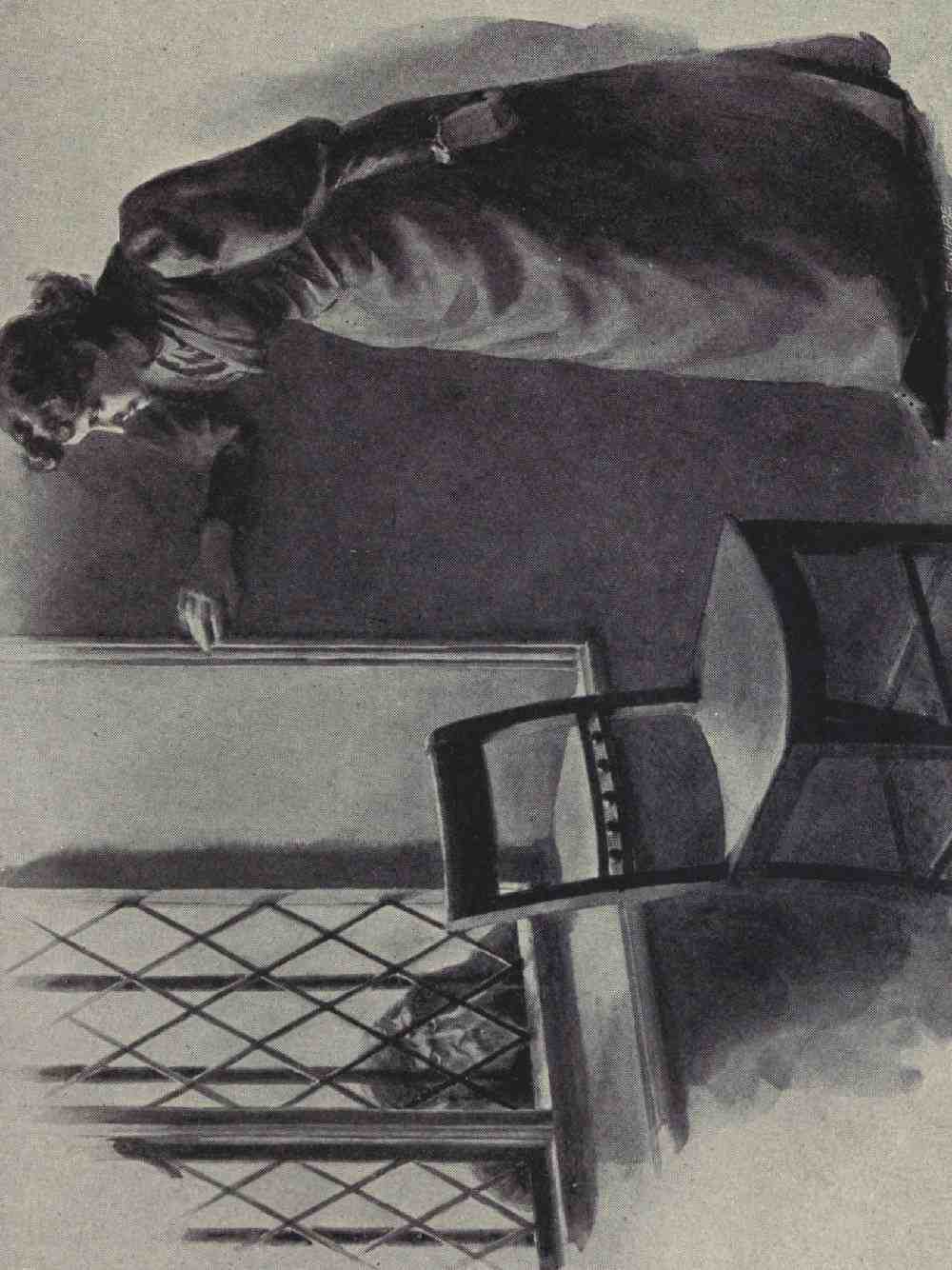

Joan sat silent, making no answer. For a few moments he waited as though expecting her to move, then he rose and came towards her with outstretched arms.

Seeing his intention, she sprang from her chair and slipped to the other side of the table.

“Come,” he said, “don’t run from me, for our courting days are over, and it’s silly in a wife. Are you going to say what I asked you, Joan?”

“No,” she answered in a quiet voice, for her instincts overcame her fears; “I have promised to live with you, though you know why I married you, and I’ll do it till it kills me, even if you are mad; but I’ll not tell you a lie, for I never promised to love you, and I hate you now more than ever I did.”

Samuel turned deadly white, then poured out a glass of neat brandy and drank it before he answered.

“That’s straight, anyway, Joan. But it’s queer that while you won’t lie to me of one thing you ain’t above doing it about another. P’raps you didn’t know it, but I was there to-day when you had your ‘few words’ with your lover. He never saw me, but I followed him from Bradmouth step for step, though sometimes I had to hide behind trees and hedges to do it. You see I thought he would lead me to you; and so he did, for I saw you kissing and hugging —yes, you who belong to me—I saw you holding that man in your arms. Mad, do you say I am? Yes, I went mad then, though mayhap if you’d done what I asked you just now I might have got over it, for I felt my brain coming right; but now it is going again, going, going! And, Joan, since you hate me so bad, there is only one thing left to do, and that is——” And with a wild laugh he dashed towards the mantelpiece to reach down the gun which hung above it.

Then Joan’s nerve broke down, and she fled. From the house itself there was no escape, for every door was locked; so, followed by the madman, she ran panting with terror upstairs to the room where she had washed her hands, and, shutting the door, shot the strong iron bolt not too soon, for next instant her husband was dashing his weight against it. Very shortly he gave up the attempt, for he could make no impression upon oak and iron; and she heard him lock the door on the outside, raving the while. Then he tramped downstairs, and for a time there was silence. Presently she became aware of a scraping noise at the lattice; and, creeping along under shelter of the wall, she peeped round the corner of the window place. Already the light was low, but she could see the outlines of a white face glowering into the room through the iron bars without. Next instant there was a crash, and fragments of broken glass fell tinkling to the carpet. Then a voice spoke, saying, “Listen to me, Joan: I am here, on a ladder. I won’t hurt you, I swear it; I was mad just now, but I am sane again. Open the door, and let us make it up.”

Joan crouched upon the floor and made no answer.

Now there came the sounds of a man wrenching at the bars, which apparently withstood all the strength that he could exert. For twenty minutes or more this went on, after which there was silence for a while, and gradually it grew dark in the room. At length through the broken pane she heard a laugh, and Samuel’s voice saying:

‘A white face glowering into the room.’

“Listen to me, my pretty: you won’t come out, and you won’t let me in, but I’ll be square with you for all that. You sha’n’t have any lover to kiss to-morrow, because I’m going to make cold meat of him. It isn’t you I want to kill; I ain’t such a fool, for what’s the use of you to me dead? I should only sit by your bones till I died myself. I’ve gone through too much to win you to want to be rid of you so soon. You’d be all right if it wasn’t for the other man, and once he’s gone you’ll tell me that you love me fast enough; so now, Joan, I’m going to kill him. If he sticks to what I heard him tell his servant this morning, he should be walking back to Rosham in about an hour’s time, by one of the paths that run past Ramborough Abbey wall. Well, I shall be waiting for him there, at the Cross-Roads, so that I can’t miss him whichever way he comes, and this time we will settle our accounts. Good-bye, Joan: I hope you won’t be lonely till I get home. I suppose that you’d like me to bring you a lock of his hair for a keepsake, wouldn’t you? or will you have that back again which you gave him this day the dead brat’s, you know? You sit in there and say your prayers, dear, that it may please Heaven to make a good wife of you; for one thing’s certain, you can’t get out,” and he began to descend the ladder.

Joan waited awhile and then peered through the window. She believed little of Samuel’s story as to his design of murdering Henry, setting it down as an idle tale that he had invented to alarm her. Therefore she directed her thoughts to the possibility of escape.

While she was thus engaged she saw a sight which terrified her indeed: the figure of her husband vanishing into the shadows of the twilight, holding in his hand the double-barrelled gun with which he had shot the dog and threatened her. Could it, then, be true? He was walking straight for Ramborough, and swiftly walking like a man who has some purpose to fulfil. She called to him wildly, but no answer came; though once he turned, looking towards the house, threw up his arm and laughed.

Then he disappeared over the brow of the slope.