THE SHADOW CURSE OF THE RAGGEDSTONE.

Near the middle of England, where the Malvern Hills rise abruptly to a height of nearly 1,400 feet above the sea, is the double-peaked rugged Raggedstone hill about which several strange old legends centre. A restless spirit is said to haunt the bleaker portions of the summit, but a stranger legend is that of the Shadow Curse, called down upon this hill by a monk of Little Malvern in the olden time.

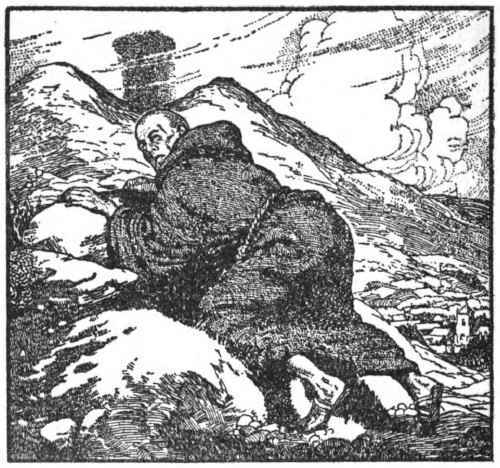

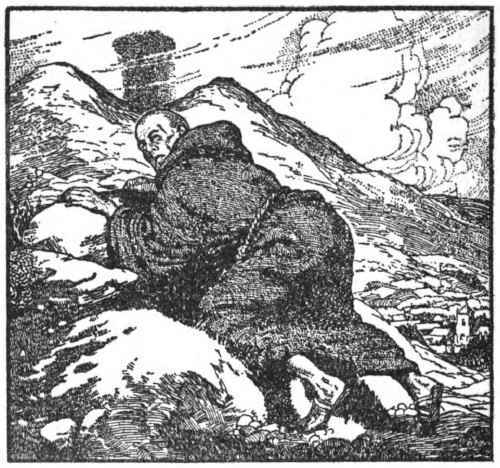

Little Malvern lies in the plain at the foot of these hills, and at the Benedictine monastery there, as the old story tells, there was once a rebellious brother. His offences against the monastic discipline were so serious that the Prior decreed, as his punishment, that he should crawl on hands and knees every day and in all weather, for a certain period, from the monastery to the top of the Raggedstone and back again.

The wretched monk had to obey, and day after day, week after week, he performed his penance. But the pain and degradation of his task embittered him, and they say that before his punishment was completed he died upon the hill of exhaustion and humiliation. Others say that he sold his soul to the devil in order to be free of his hated task, but anyhow before he disappeared from human ken, he put a bitter curse upon the hill that had caused him so much suffering.

He cursed with death or misfortune whomsoever the shadow of the hill should fall upon, having in mind that in those days of sparsely populated land the people who would suffer most would be the Prior and his brethren in the monastery beneath.

Now the shadow of the Raggedstone is very seldom seen. Only at rare times when the sun is shining between the twin peaks does it appear, and those who have seen it describe it as a weird cloud, black and columnar in shape, which rises up between the two summits and moves slowly across the valley.

Many stories were told, in times past, of the misfortunes that happened to those upon whom this uncanny shadow fell; and it is recorded that Cardinal Wolsey was once caught by this weird cloud, and to that the old folk attributed the misfortune that came to the proud man when at the height of his power.

Wolsey in his early days was a tutor to the Nanfan family whose house was at Birts Morton Court, a couple of miles from the foot of Raggedstone. The young tutor fell asleep in the orchard one day, and awoke suddenly, shivering, to find the strange unearthly shadow moving across the trees.

Much of Little Malvern Priory, the home of that miserable monk of long ago, remains to-day. Its domestic buildings are almost intact, with amazing good fortune having escaped the common fate of such edifices. There are, too, the old monkish fish ponds, now lily spangled in spring time, and an old preaching cross. The parish church is part of the old priory church and contains a finely carved rood screen and some most interesting stained glass.

Great Malvern, some three miles away, clinging as it were to the side of the great Worcestershire Beacon, is a place with world-wide fame. It, too, has its great priory church, and all the attractions and conveniences of a favourite inland resort.

But the chiefest charm of the Malverns—there are seven of them—is their hills. These form a glorious range, of varying barren and wooded mountainous country, flung as it were as a far outpost beyond Severn of the wild Welsh mountains many miles to the westward.

The view from these Malvern Hills is, perhaps, unequalled. They say nobody knows exactly how much of England and Wales can be seen from them. Fifteen counties are certain, and in that range is included the Wrekin, the Mendips, and the Welsh mountains as far as Plinlimmon.

On the fine upstanding Herefordshire Beacon is, perhaps, the best specimen of an ancient British camp that we have. Tradition says that here Caractacus defended himself from the Romans.

It was “on a May morning on Malverene Hulles” that Piers Plowman had that vision of which Langland wrote five hundred and more years ago.

Few centres in our country offer such varied scope to the holiday-maker as the Malverns, where nature and history vie with one another in the matter of attractions.

The fresh upland air is tonic and health-giving. That weird dark shadow of the Raggedstone can never have fallen here, or, if it have, its mystical power has become impotent by reason of the many beauties of the place.

The Malvern Hills.