(VI)

(VI)

DAY and night she lived for seven months in the dim light and unceasing movement of my cabin, and gradually an intimacy was established between us, simultaneously with a faculty of mutual comprehension very rare between man and animal.

I recall the first day when our relations became truly affectionate. We were far out in the Yellow Sea, in gloomy September weather. The first autumnal fogs had gathered over the suddenly cooled and restless waters. In these latitudes cold and cloud come suddenly, bringing to us European voyagers a sadness whose intensity is proportioned to our distance from home. We were steaming eastward against a long swell which had arisen, and rocked in dismal monotony to the plaintive groans and creakings of the ship. It had become necessary to close my port, and the cabin received its sole light through the thick bull’s-eye, past which the crests of the waves swept in green translucency, making intermittent obscurity. I had seated myself to write at the little sliding table, the same in all our cabins on board,—during one of those rare moments, when our service allows a complete freedom and peace, and when the longing comes to be alone as in a cloister.

Pussy Gray had lived under my berth for nearly two weeks. She had behaved with great circumspection; melancholy, showing herself seldom, keeping in darkest corners as if suffering from homesickness and pining for the land to which there was no return.

Suddenly she came forth from the shadows, stretched herself leisurely, as if giving time for farther reflection, then moved towards me, still hesitating with abrupt stops; at times affecting a peculiarly Chinese gesture, she raised a fore paw, holding it in the air some seconds before deciding to make another advancing step; and all this time her eyes were fixed on mine with infinite solicitude.

What did she want of me? She was evidently not hungry: suitable food was given her by my servant twice daily. What then could it be?

When she was sufficiently near to touch my leg, she sat down, curled her tail about her, and uttered a very low mew; and still looked directly in my eyes, as if they could communicate with hers, which showed a world of intelligent conception in her little brain. She must first have learned, like other superior animals, that I was not a thing, but a thinking being, capable of pity and influenced by the mute appeal of a look; besides, she felt that my eyes were for her eyes, that they were mirrors, where her little soul sought anxiously to seize a reflection of mine. Truly they are startlingly near us, when we reflect upon it, animals capable of such inferences.

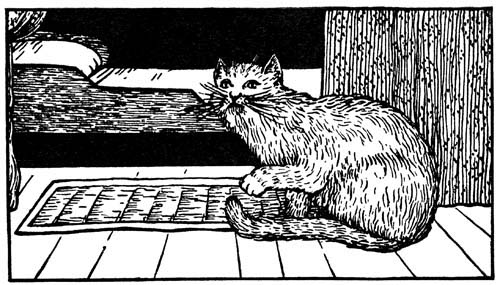

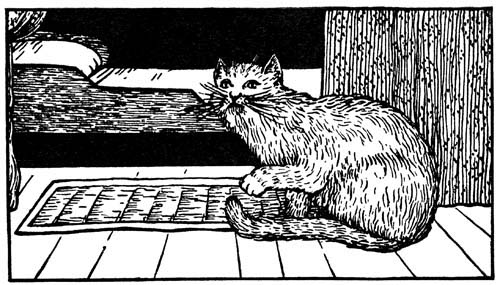

“AND STILL LOOKED DIRECTLY IN MY EYES”

As to myself, I studied for the first time the little visitor who for two weeks had shared my lodging: she was fawn-colored like a wild rabbit, mottled with darker spots like a tiger, her nose and neck were white; homely in effect, mainly consequent on her extremely thin and sickly condition, and really more odd looking than homely to a man freed like myself from all conventional ideas of beauty. Besides, she was quite unlike our French cats: low on the legs, very long bodied, a tail of unusual length, large upright ears, and a triangular face; all her charm was in the eyes, raised at the outer corners like all eyes of the extreme Orient, of a fine golden yellow instead of green, and ever changing, astonishingly expressive.

While examining her, I laid my hand gently upon her queer little head, stroking the brown fur in a first caress.

Whatever she experienced was an emotion beyond mere physical pleasure; she felt the sentiment of a protection, a pity for her condition of an abandoned foundling. This, then, was why she came out of her retreat, poor Pussy Gray; this was why she resolved, after so much hesitation, to beg from me not food or drink, but, for the solace of her lonely cat soul, a little friendly company and interest.

Where had she learned to know that, this miserable outcast, never stroked by a kind hand, never loved by any one,—if not perhaps in the paternal junk, by some poor Chinese child without playthings, and without caresses, thrown by chance like a useless weed in the immense yellow swarm, miserable and hungry as herself, and whose incomplete soul in departing, left behind no more trace than her own?

Then a frail paw was laid timidly upon me—oh! with so much delicacy, so much discretion!—and after looking at me a long time beseechingly, she decided to venture upon my knee. Jumping there lightly she curled herself in a light, small mass, making herself small as possible and almost without weight, never taking her eyes from me. She lay a long time thus, much in my way, but I had not the heart to dislodge her, which I should doubtless have done had she been a gay pretty kitten in the bloom of kittenhood. As if in fear at my least movement, she watched me incessantly, not fearing that I should harm her—she was too intelligent to think me capable of that—but with an air that seemed to ask: “Is it true that I do not weary you, that I do not trouble you?” and then, her eyes growing still more tender and expressive, saying to mine very plainly: “On this dismal autumn day, so depressing to the soul of cats, since we two are here so lonely, in this abode so strange, so unquiet, shaken and lost amid I know not what dangerous and endless space, can we not give to each other a little of that sweet thing, immaterial and beyond the power of death, which is called affection and which sometimes shows itself in a caress?”