(IV)

(IV)

AS the oldest, allow me first to present the Angora, Pussy White. Her visiting card, by her desire, was thus inscribed—

MADAME MOUMOUTTE BLANCHE

PREMIÈRE CHATTE

Chez M. Pierre Loti.

On a memorable evening nearly twelve years ago, I saw her for the first time. It was a winter’s evening, on one of my returns home at the close of some Eastern campaign. I had been in the house but a few moments, and was warming myself before a blazing wood fire, seated between my mother and my aunt Clara. Suddenly something appeared on the scene, bounding like a panther, and then rolling itself wildly on the hearth rug like a live snowball on its crimson ground. “Ah!” said aunt Clara, “you don’t know her; I will introduce her; this is our new inmate, Pussy White! We thought we would have another cat, for a mouse had found our closet in the saloon below.”

The house had been catless for a long time; succeeding the mourning for a certain African cat that I had brought home from my first voyage and worshiped for two years, but who one fine morning, after a short illness, breathed out her little foreign soul, giving me her last conscious glance, and whom I had afterward buried beneath a tree in the garden.

I lifted for a closer view the roll of fur which lay so white on the crimson mat. I held her carefully with both hands, in a position cats immediately comprehend, and say to themselves, “Here is a man who understands us; his caresses we can gratefully condescend to receive.”

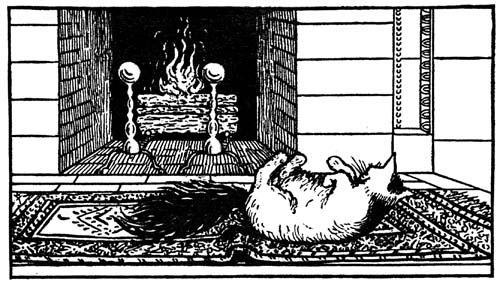

The face of the new cat was very prepossessing. The young, brilliant eyes, the tip of a pink nose, and all else lost in a mass of silken Angora fur; white, warm, clean, exquisite to fondle and caress. Besides, she was marked nearly like her predecessor from Senegal, which fact probably decided the selection of my mother and aunt Clara,—to the end that I might finally regard the two as one, in my somewhat fickle affections. Above the cat’s ears, a capote shaped spot, jet black in color, was set straight, forming a band over the bright eyes; another and larger spot, shaped like a cape, lay over her shoulders; a plumy black tail, moving like a superb train or an animated fly-brush, completed the costume. Her breast, belly, and paws were white as the down of a swan; her “total” gave me the impression of a ball of animated fur; light, soft, and moved by some capricious hidden spring. After making my acquaintance, Pussy White left my arms to recommence her play. And in these first moments of arrival, inevitably melancholy, because they marked another epoch in my life, the new black and white cat obliged me to busy my thoughts with her, jumping on my knee to reiterate my welcome, or stretching herself with feigned weariness on the floor, that I might better admire the silken whiteness of her belly and neck. So she gambolled, the new cat, while my eyes rested with tender remembrances on the two dear faces which smiled on me, somewhat aged and framed in grayer curls; upon the family portraits which preserved their expression and age in their frames upon the walls; upon the thousand objects seen in their accustomed places; upon the well known furniture of this hereditary dwelling immovably fixed there, while my unquiet, restless, changing being had roamed over a changing world.

And this is the persistent, distinct image of our Pussy White, with me still, long after her death: an embodied frolic in fur, snowy white and bounding or rolling on the crimson rug between the sombre black robes of my mother and aunt Clara, in the evening of one of my great returns.

“ROLLING ON THE CRIMSON RUG”

Poor Pussy! During the first winter of her life she was usually the familiar demon, the hearthstone imp, who enlivened the loneliness of the blessed guardians of my home, my mother and aunt Clara. While I sailed over distant seas, when the house resumed its grand emptiness, in sombre twilights and interminable December nights, she was their constant attendant, though often their tormentor; leaving upon their immaculate black gowns, precisely alike, tufts of her white fur. With reckless indiscretion she took forcible possession of a place on their laps, their work table, or in the centre of their workbaskets, tangling beyond rearrangement their skeins of wool, their reels of silk. Then they would say with great pretense of anger, meanwhile longing to laugh, “Oh! that cat, that bad cat, she will never learn how to behave herself! Get out, miss! Get out! Were there ever such actions as these!” They busied themselves inventing methods for her amusement, even to keeping a jumping-jack, a ludicrous wooden toy, for her special edification.

She loved them cattishly, with indocility, but added thereto a touching constancy, for which alone her little incomplete and fantastic existence merits my lasting remembrance.

In springtime, when the March sun began to brighten our courtyard, she experienced new and endless surprises in seeing, awake and crawling from his winter retreat, our tortoise Suleïma, her fellow resident and friend.

During the beautiful month of May she seemed seized by yearnings for space and freedom; then she made excursions on the walls, the roof, through the lanes, in the neighboring gardens, and even nocturnal absences, which I should here state were unaccountable in the austere circle where fate had placed her.

In summer she was languid as a creole. For entire days she lay lazily in the sunshine on the old wall top among the honeysuckles and roses, or, extended on the tiled walks, turned her white belly to the sun amidst the pots of red or golden cacti.

Extremely careful of her little person, always neat, correct, aristocratic, even to the ends of her toes, she was haughtily disdainful of other cats, and conducted herself as if ill bred if any neighbor cat called on her. In this courtyard, which she considered her own domain, she conceded no right of entry. If, above the adjoining garden wall, two ear tips, a cat’s nose, rose timidly, or if something stirred in the vines or moss, she upsprang like a young fury, bristling angrily to the tip of her tail, impossible to restrain, quite beside herself! Cries in harsh tones and bad taste followed, struggles, blows, and savage clawings.

In fact, our pet was ferociously independent. She was also extremely affectionate when so inclined, caressing, cajoling, uttering so gentle a cry of joy, a tremulous “miaou” every time she returned from one of her vagabond tramps in the vicinity.

She was then five years old, in the mature beauty of an Angora, with superb attitudes of dignity and the graces of a queen. I had become much attached to her in the course of my absences and returns, considering her one of our home treasures, when there appeared on the scene—three thousand miles afar in the Gulf of Pekin, and of a far less distinguished family than the Angoras—the kitten destined to become her inseparable friend, the most unique little personage I have yet known, “Pussy Gray” or “Pussy Chinese.”