III

THE PAWNEES ARE OF TWO MINDS

“The Kansas are coming! They come in peace, but make ready for them.”

These were the words of the heralds shouting through the great town of the Pawnee Republic. Scar Head heard. He had returned this morning from the American camp with the interpreter (whose name was Baroney), and felt rather important as the other boys curiously questioned him. To Chief White Wolf he had only good to report of the Americans. They had treated him well, aside from bothering him with talk about himself; but he had told them little. The fact was, he did not know much that he could tell!

Baroney had wished to trade for provisions and horses. Now it was afternoon, and new excitement arose. The Kansas were coming! A peace party of them had halted, out on the prairie, and had sent in one man to announce them. They had come by order of the American father, to smoke peace with the Osages.

The Osages and the Kansas had long been bitter enemies; the Pawnees, too, had lost many scalps to the Kansas, although just at present there was no war between them.

So Chief Charakterik directed that the Kansas be well received and feasted. Baroney the American interpreter took word up to the Pike camp that the Kansas were waiting.

The two American chiefs exchanged visits with Chiefs White Wolf and Rich Man, and the Kansas chiefs. In a council held the next day the Kansas principal chief, Wah-on-son-gay, and his sub-chiefs, and the Osage principal chief, Shin-ga-wa-sa or Pretty Bird, and his sub-chiefs, agreed upon paper that the nations of the Kansas and the Osage should be friends, according to the wish of their American father.

Wolf, the Pawnee, laughed.

“It will last only until spring,” he said. “Nobody can trust the Kansas; and as for those Osage, they are getting to be a nation of squaws. One-half their face is red, the other half is white. We Pawnee are all red. We are not afraid of the Kansas, and we shall not help the Americans. They are a small people of small hearts, as the Spanish chief said.”

This might appear to be the truth. Chief Charakterik was of the same opinion. He and Second Chief Iskatappe and two sub-chiefs had been invited to a feast by the American chiefs. When they returned they were scornful, although White Wolf had been given a gun with two barrels, an arm band, and other things, and the other chiefs also had been rewarded.

Scar Head heard Rich Man tell about it.

“Charakterik wore his large medal given him by the young Spanish chief. They did not ask him to take it off. They offered me a little American medal. ‘What shall I do with that?’ I asked. ‘It is not a medal for a chief. Those two young warriors who have been to Wash’ton were given bigger medals than this. Let the American father send me a chief’s medal, for I can get Spanish medals. I am not a boy.’ Yes,” continued Iskatappe, “the American nation must be very mean and stingy. They send a young man and a few soldiers, with little medals and a few poor presents, to talk with the great Pawnee nation. But the Spanish asked us to wait until next spring, when they will send us a principal chief and many more soldiers, to live near us and treat with us in honorable fashion.”

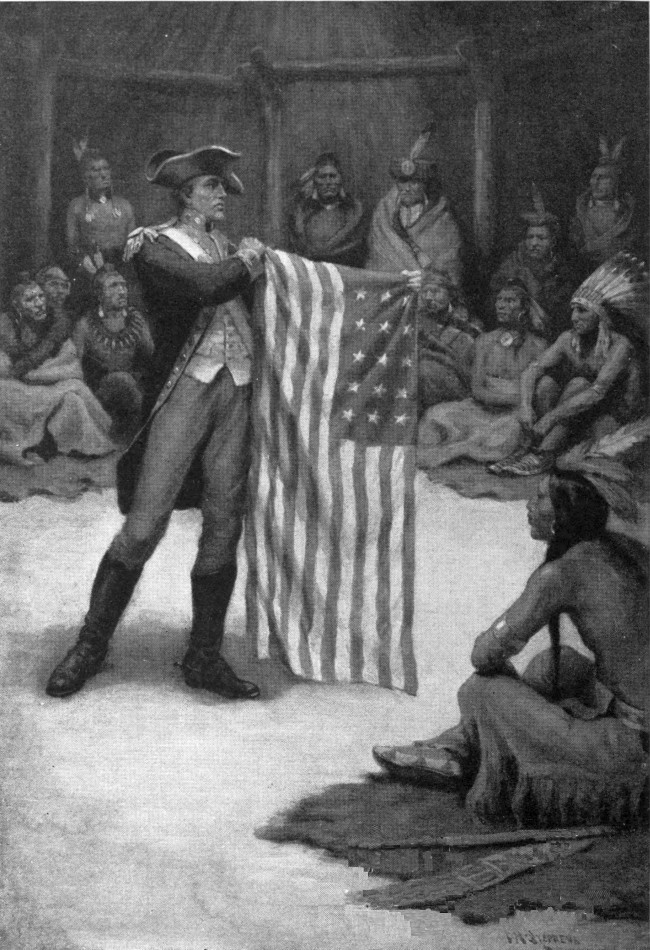

The council with the Americans had been set for the next day. The two American chiefs, and Baroney the interpreter, and the “doctor,” and a guard of soldiers, rode down. Chief Charakterik assembled four hundred warriors. The council lodge was crowded, and a throng of women and boys and girls pressed around, outside, to peer and listen. Scar Head managed to squeeze inside, to a place where he might see and hear. The Osages and the Kansas were inside, too.

After the pipe had been passed around among the chiefs, Mungo-Meri Pike stood, to speak. He threw off his red-lined blue cloak, and stood slim and straight—a handsome young man.

Baroney translated for him, in Pawnee and sign language.

“The great American father of us all, at Wash’ton, has sent me,” he said. “He is now your father. You have no Spanish father. Not long ago the Spanish gave up all this country, from the big river to the mountains. The Americans have bought it. The Spanish have no rights here, any more. Now your American father has sent me to visit among his red children, to tell them that his heart is good toward them, and that he wishes peace. I am to take back word of them, and of the country, so that he may know. I am surprised to see that you are flying the Spanish flag at the lodge door. I bring you the American flag, to take its place. You cannot have two fathers and two flags. I have also brought you gifts. They are here. I ask you to accept them, as a small token from your American father. I should like your answer.” And he sat down.

“I BRING YOU THE AMERICAN FLAG”

Chief Charakterik dropped his buffalo-robe from his shoulders, to stand and speak.

“We hear your words,” he said. “We thank you for the presents. We wish to ask where you are going from here?”

“We are going on, to explore the country and to smoke peace with the Ietans,” replied Chief Pike.

“We knew that you were coming,” spoke White Wolf. “The Spanish chief who was here said that you were coming. He said that the Americans were a small nation but greedy, and that soon they would stretch out even to the Pawnee, and claim the country. Now we see how truly the Spanish chief saw ahead, for here you are. We do not wish you to go on. We turned the Spanish back, until they should come again to live with us. We will turn you back. It is impossible for you to go on. You are few and you do not know the country. The Padoucah (Comanches) are many and powerful. They are our enemies and the friends of the Spanish and will kill you all. You must go back by the road that you came on.”

The young Chief Mungo-Meri Pike stood up straighter still, and answered with ringing voice.

“I have been sent out by our great father to travel through his country, to visit his red children, and talk peace. You have seen how I have brought the Osages and the Kansas together. I wish my road to be smooth, with a blue sky over my head. I have not seen any blood in the trail. But the warriors of the American father are not women, to be turned back by words. If the Pawnee wish to try to stop me, they may try. We are men, well armed, and will take many lives in exchange for our own. Then the great father will send other warriors, to gather our bones and to avenge our deaths, and our spirits will hear war-songs sung in praise of our deeds. We shall go on. I ask you for horses, and somebody who speaks Comanche, to help us; and I ask you to take down the Spanish flag and hoist the flag of your American father, instead.”

That was a defiant speech, and Scar Head thrilled. Surely, the American chief was a man.

Iskatappe arose.

“We do not want peace with the Padoucah,” he said. “They have killed six of our young men. We must have scalps in payment, so that the young men’s relatives can wash the mourning paint from their faces and be happy. It would be foolish for us to send anybody with you or to give you horses. We have been satisfied with our Spanish father. We do not wish so many fathers.”

He sat down.

“That is true,” Chief Pike retorted. “You do not wish many fathers. Now you have only the one great father. He is your American father. You have not answered me about the flag. I still see the Spanish flag flying at your door. I think you ought to lower that flag and put up this American flag, for I have told you that the Spanish do not rule this land any more. You cannot be children of two fathers, and speak with two tongues. I wish an answer.”

Nobody said anything for a long time. The American chiefs sat there, gazing straight in front of them, and waiting. The blue eyes of Mungo-Meri Pike seemed to search all hearts. Was it to be peace or war? Then old Sleeping Bear, the head councillor of the Pawnee Republic, got up, without a word, and went to the doorway, and took down the Spanish flag from its staff, and brought it to Chief Pike. Chief Pike handed him the American flag, of red and white stripes like the sunset and the starry sky in one corner. Old Sleeping Bear carried it and fastened it to the staff.

The Osages and the Kansas grunted “Good,” because they already had accepted the American father; but the Pawnees hung their heads and looked glum. When the Spanish came back and found their great king’s flag gone, what would they say?

Chief Pike saw the downcast faces, and read the thoughts behind them. His heart was big, after all, and he did not wish to shame the Pawnee nation, for he uttered, quickly:

“You have shown me that you are of good mind toward your father in Wash’ton. I do not seek to make trouble between you and the Spanish. We will attend to the Spanish. Should there be war between the white people, the wish of your American father is that his red children stay by their own fires and not take part. In case that the Spanish come and demand their flag, here it is. I give it to you. I ask that you do not put it up while I am with you, but that you keep the American flag flying.”

“We thank you. We will do as you say,” White Wolf responded; and every face had brightened. “In return, we beg you not to go on. You will lose your way. It will soon be winter, and you have no winter clothes, I see. The Spanish will capture you. If they do not capture you, the Padoucah will kill you. It will be pitiful.”

Soon after this the council broke up. Chief Mungo-Meri Pike was still determined; he had not been frightened by the words. His men tried to buy horses, but Chief White Wolf had the orders spread that no horses were to be supplied to the Americans. When some of the Pawnees went to the American camp, to trade, Skidi and two other “dog soldiers” or police followed them and drove them home with whips of buffalo-hide.

Iskatappe only waited for other orders, to muster the warriors and capture the camp.

“It can be done,” he said. “We doubtless shall lose many men, for I think the Americans are hard fighters. We might do better to attack them on the march.”

Some of the older men were against fighting.

“We should not pull hot fat out of the fire with our fingers, for the Spanish,” they said. “Let the Spanish stop the Americans, if they can. We will stay at home and put up the flag of the stronger nation.”

Meanwhile the young warriors liked to gallop near the American camp and shake their lances and guns at it. The American warriors laughed and shouted.

For the next few days Boy Scar Head was all eyes and ears. The Americans kept close in camp and were very watchful. Only Baroney the interpreter rode back and forth, looking for horses. Chief Charakterik seemed much troubled. He had not counted upon the Americans being so stubborn. He sent the Kansas home. They had promised to guide the Americans; but he gave Wah-on-son-ga a gun and two horses, and told him that the Padoucahs would certainly kill everybody; so Wah-on-son-ga took his men home.

Frank, the Pawnee-who-had-been-to-Wash’ton, stole the wife of an Osage and ran away with her. This made the Osages angry; and now the Americans were getting angry, too.

They had found only three or four horses. Then—

“The Americans are going to march to-morrow!”

That was the word from the warriors who spied upon the camp. Chief Pike rode down, unafraid, with Baroney, to White Wolf’s lodge. Scar Head hid in a corner, to hear what was said. He liked the crisp voice and the handsome face of this young Mungo-Meri Pike. Maybe he would never see him again.

“Why have you told the Kansas to go home, and made them break their promise to me?” demanded Chief Pike, of White Wolf.

“The hearts of the Kansas failed them. They decided they would only be throwing their lives away, to go with such a small party into the country of the Padoucah,” answered White Wolf.

“You frightened them with your stories,” Chief Pike accused. “That was not right. I have come from your father, to make peace among his red children. Why do you forbid your men to trade us horses? You have plenty. Why do you not lend us a man who speaks the Ietan tongue, to help us?”

“If, as you say, we all are children of the American father, then we do not wish our brothers to give up their lives,” White Wolf said. “But we do not know. The Spanish claim this country, too. They are coming back next spring. We promised them not to let you march through. You can come next spring and talk with them.”

“No!” thundered Chief Pike. “We are going to march on. We are Americans and will go where we are ordered by the great father. The Osages have given us five of their horses. They have shown a good heart. I will speak well of them, to their father.”

“They gave you their poor horses, because they got better ones from us,” replied White Wolf.

“If the Pawnee try to stop us, it will cost them at least one hundred warriors,” Chief Pike asserted. “You will have to kill every one of us, and we will die fighting. Then the American nation will send such an army that the very name Pawnee will be forgotten.” He arose, and his flashing blue eyes marked Boy Scar Head huddled upon a roll of buffalo-robes. “Who is that boy?” he asked.

“He is my son,” Charakterik answered.

“He cannot be your son,” reproved Chief Pike. “He is white, you are red. I think he is an American. Where did you get him?”

“He is my son. I have adopted him,” White Wolf insisted. “I got him from the Utahs.”

“Where are his parents?”

“I am his parent. I do not know anything more.”

“You must give him up. He is not an Indian,” said Chief Pike.

“He is a Pawnee. Why should I give him up?” argued Charakterik.

“Because the great father wishes all captives to be given up. The Potawatomi had many captives from the Osage. They have been given up. There cannot be good feeling between people when they hold captives from each other. I ask you to send this boy down river. Two French traders are in your town now. You can send the boy with them.”

“I will think upon what you say,” White Wolf replied.

So Chief Pike left.

“Why did you come in here to listen?” scolded White Wolf, of Scar Head. “You are making me trouble. Do you want to be sent away with those traders?”

“No,” Scar Head admitted. For the two French traders were dark, dirty little men, not at all like the Americans. He preferred the Pawnees to those traders. But if he were an American, himself——? An American the same as the Pike Americans! That sounded good.

He could see that White Wolf was troubled; and the rest of the day he kept out of sight. Early in the morning the two French traders went away, but he had not been sent for. Chief Charakterik probably had matters of more importance to think about.

The Americans were breaking camp. The Pawnee young men, urged by Iskatappe and Skidi, were painting for battle, while the women filled the quivers and sharpened the lance points, and cleaned the guns afresh.

The sun mounted higher. A close watch was kept upon the American camp, plain in view up the Republican River. Shortly after noon the cry welled:

“They are coming! Shall we let them pass?”

“No! Kill them!”

“See where they are going, first.”

“Wait till they are in the village.”

Nobody knew exactly what to do. The Americans were marching down, their horses together, their ranks formed, their guns ready; and they looked small beside the four hundred and more warriors of the Pawnees. It was a brave act.

“They are not striking the village. They are going around,” Rich Man shouted. “We shall have to fight them in the open. That is bad.”

The young warriors like Skidi ran to and fro, handling their bows and lances and guns. They waited for orders from White Wolf; but White Wolf only stood at the door of his lodge, with his arms folded, and said nothing as he watched the American column.

Mungo-Meri Pike was smart. He acted like a war chief. He was marching around, far enough out so that if he were attacked the Pawnees could not hide behind their mud houses. Now to charge on those well-armed Americans, in the open, would cost many lives; and no Pawnee wished to be the first to fall.

The Americans had come opposite, and no gun had yet been fired, when on a sudden Chief Pike left them. With Baroney and one soldier he galloped across, for the village. That was a bold deed, but he did not seem to fear. He paid no attention to the warriors who scowled at him. He made way through them straight to Chief Charakterik. He spoke loudly, so that all about might hear.

“I have come to say good-by. I hope that when we come again we will find the great father’s flag still flying.”

“You had better go quickly,” White Wolf replied. “The Spanish will be angry with us, and my young men are hard to hold.”

“We are going,” Chief Pike assured. “We are going, as we said we would. If your young men mean to stop us, let them try. Two of our horses were stolen from us this morning. They were Pawnee horses. One was returned to us by your men. The other is missing. I am sure that the Pawnee do not sell us horses at a high price, so as to steal them. That is not honest. If you are a chief you will get the horse back for us, or the Pawnee will have a bad name for crooked tongues. So I will leave one of my men, who will receive the horse and bring it on. He will wait till the sun is overhead, to-morrow.”

“I will see what I can do,” White Wolf answered. “The horse may have only strayed. A present might find him again.”

“The horse is ours,” reproved Chief Pike. “I shall not buy it twice. If the Pawnees are honest and wish to be friends with their American brothers, they will return the horse to me. I shall expect it, to-morrow. Adios.”

“Adios,” grunted White Wolf, wrapping his robe about him.

Chief Pike and Baroney the interpreter galloped for the column. They left the soldier. Now he was one American among all the Pawnees, but he did not act afraid, either.

He sat his horse and gazed about him with a smile. He was a stout, chunky man, in stained blue clothes. His face was partly covered with red hair, and the hair on his head, under his slouched black hat, was red, too. He carried a long-barreled heavy gun in the hollow of one arm.

“Get down,” signed White Wolf. “Come into my lodge.” And he waved the crowding warriors back.

The red-haired soldier got down and entered the lodge. Here he was safe. Everything of his was safe as long as he was a guest of a lodge. Scar Head slipped in after him, but White Wolf stayed outside.

“The American chief has lost a horse,” he announced. “The horse must be brought back, or we shall have a bad name with our American father.”

“If the American chief has lost a horse, let him promise a present and maybe it will be found,” answered Skidi.

“That is no way to talk,” Charakterik rebuked. “I want the horse brought to me; then we will see about the present.”

“The present is here already,” laughed Skidi. “It is in your lodge. The American chief would have done better to lose all his horses and say nothing, for a red scalp is big medicine.”

And all the warriors laughed.

Inside the lodge the American soldier grinned at Scar Head. Scar Head grinned back.

“Hello,” said the soldier.

Scar Head had heard that word several times. Now he blurted it, himself.

“H’lo.”

This was the end of the conversation, but Scar Head did a lot of thinking. He well knew where the horse was. Skidi had stolen it and hidden it out, and boasted of his feat. Now Skidi was talking of keeping the red-hair. That did not seem right. The Americans were brave. If somebody—a boy—should go out and bring the horse in, then Skidi might not dare to claim it, and White Wolf would send it and the red-hair on to Pike, and there would be no more trouble. Yes, being an American, himself (as they had said), Scar Head decided that he ought to help the other Americans.

He would get the horse.