XIV

A TRAIL OF SURPRISES

The lieutenant had explored the source of this Red River far enough. He was ready to march on down, for the plains and the United States post of Natchitoches above the mouth in Louisiana. Everybody was glad.

The big meals of buffalo meat had made several of the men, and Stub also, quite ill; so that on the day after Christmas the march covered only seven miles. The tent was turned into a hospital, and the lieutenant and the doctor slept out in the snow.

The Great White Mountains, far to the east, had been in sight from high ground; the river appeared to lead in that direction. But here at the lower end of the bottom-land other mountains closed in. The river coursed through, and everybody rather believed that by following it they all would come out, in two or three days, into the open.

That proved to be a longer job than expected, and the toughest yet. The river, ice-bound but full of air-holes, sometimes broadened a little, and gave hope, but again was hemmed clear to its borders by tremendous precipices too steep to climb. The poor horses slipped and floundered upon the ice and rocks; in places they had to be unpacked and the loads were carried on by hand.

Soon the lieutenant was ordering sledges built, to relieve the horses of the loads; men and horses both pulled them—and now and then sledge and horse broke through the ice and needs must be hauled out of the water.

Twelve miles march, another of sixteen miles, five miles, eight miles, ten and three-quarter miles, about five miles—and the river still twisted, an icy trail, deep set among the cliffs and pinnacles and steep snowy slopes that offered no escape to better country.

The horses were so crippled that some could scarcely walk; the men were getting well bruised, too; the dried buffalo meat had dwindled to a few mouthfuls apiece, and the only game were mountain sheep that kept out of range. The doctor and John Brown had been sent ahead, to hunt them and hang the carcasses beside the river, for the party to pick up on the way.

From camp this evening the lieutenant and Baroney climbed out, to the top, in order to see ahead. They came down with good news.

“We’ve sighted an open place, before,” said the lieutenant, gladly. “It’s not more than eight miles. Another day’s march, my men, and I think we’ll be into the prairie and at the end of all this scrambling and tumbling.”

That gave great hope, although they were too tired to cheer.

But on the morrow the river trail fought them harder than ever. Toward noon they had gained only a scant half mile. The horses had been falling again and again, the sledges had stuck fast on the rocks and in the holes, the ice and snow and rocks behind were blood-stained from the wounds of men and animals.

Now they had come to a narrow spot, where a mass of broken rocks, forming a high bar, thrust itself out from the cliff, into the stream, and where the water was flowing over the ice itself. The horses balked and reared, while the men tugged and shoved.

“Over the rocks,” the lieutenant ordered.

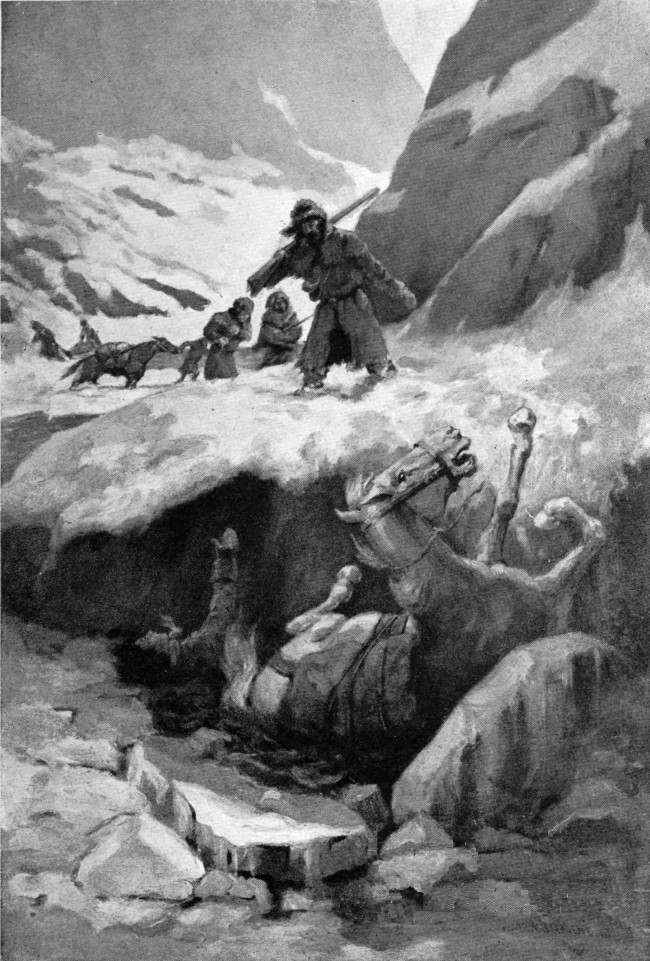

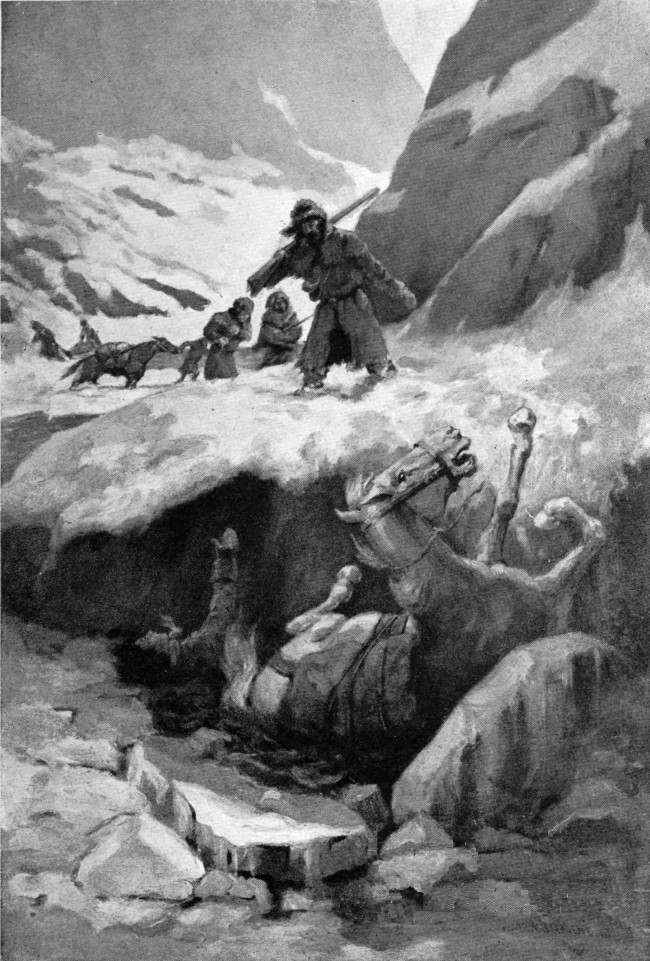

That brought more trouble. Stub’s yellow pony, thin and scarred like the rest, was among those that still carried light packs. He was a stout, plucky pony—or had been. Here he lost heart, at last. His hoofs were sore, he was worn out. Terry Miller hauled at his neck-thong, Stub pushed at his braced haunches. The line was in a turmoil, while everybody worked; the canyon echoed to the shouts and blows and frenzied, frightened snorting.

Suddenly the yellow pony’s neck-thong snapped; he recoiled threshing, head over heels, before Stub might dodge from him; and down they went, together, clear into the river. But Stub never felt the final crash. On his way he saw a burst of stars, then he plunged into night and kept right on plunging until he woke up.

BUT STUB NEVER FELT THE FINAL CRASH

He had landed. No, he was still going. That is, the snow and cliffs at either side were moving, while he sat propped and bewildered, dizzily watching them.

His head throbbed. He put his hand to it, and felt a bandage. But whose bowed back was that, just before? And what was that noise, of crunching and rasping? Ah! He was on a sledge—he was stowed in the baggage upon a sledge, and was being hauled—over the ice and snow—through the canyon—by—by——

Freegift Stout! For the man doing the hauling turned his face, and was Freegift Stout!

Well, well! Freegift halted, and let the sled run on to him. He shouted also; they had rounded a curve and there was another loaded sled, and a man for it; and they, too, stopped.

“Hello. Waked at last, have ye?” spoke Freegift, with a grin.

“Yes, I guess so.” Stub found himself speaking in a surprisingly easy fashion. A prodigious amount of words and notions were whirling through his mind. “Where—where am I, anyhow?”

“Ridin’ like a king, down the Red River.”

“What for?”

“So’s to get out an’ reach Natchitoches, like the rest of us.”

Stub struggled to sit up farther. Ouch!

“What’s your name?” he demanded. Then—“I know. It’s Freegift Stout. That other man’s Terry Miller. But what’s my name?”

“Stub, I reckon.”

“Yes; of course it is. That’s what they call me. But how did you know? How’d you know I’m ‘Stub’ for short? I’m Jack. That’s my regular name—Jack Pursley. I got captured by the Utahs, from my father; did the Pawnees have me, too? Wish I could remember. I do sort of remember. But I’m a white boy. I’m an American, from Kentucky. And my name’s Jack Pursley—Stub for short.”

Freegift roundly stared, his mouth agape amidst his whiskers.

“Hey! Come back here, Terry,” he called. And Terry Miller came back.

“That crack on the head’s set him to talkin’ good English an’ turned him into a white lad, sure,” quoth Freegift. “Did you hear him? Ain’t that wonderful, though? His name’s Jack Pursley, if you please; an’ he answers to Stub, jest the same—an’ if that wasn’t a smart guess by John Sparks I’ll eat my hat when I get one.”

“I’ll be darned,” Terry wheezed, blinking and rubbing his nose. “Jack Pursley, are you? Then where’s your dad?”

“I don’t know. We were finding gold in the mountains, and the Indians stole me and hit me on the head—and I don’t remember everything after that.”

“Sho’,” said Terry. “How long ago, say?”

“What year is it now, please?”

“We’ve jest turned into 1807.”

“I guess that was three years ago, then.”

“And whereabouts in the mountains?”

“Near the head of the Platte River.”

“For gosh’ sake!” Freegift blurted. “We all jest come from there’bouts. But you didn’t say nothin’, an’ we didn’t see no gold.”

“I didn’t remember.”

“Well, we won’t be goin’ back, though; not for all the gold in the ’arth. Were you all alone up there?”

“My father—he was there. Some other men had started, but they quit. Then we met the Indians, and they were friendly till they stole me.”

“Did they kill your father?”

“I don’t know.”

“That’s a tall story,” Freegift murmured, to Terry; and tapped his head. Evidently they didn’t believe it “Where do you think you are now, then?” he asked, of Stub.

“I guess I’m with Lieutenant Pike. But where is he?”

“Well, we’ll tell you. You see, that yaller hoss an’ you went down together. You got a crack on the head, an’ the hoss, he died. We had to shoot him. But we picked you up, because you seemed like worth savin’. The lieutenant put a bandage on you. Then he took the rest of the outfit up out the canyon. The hosses couldn’t go on—there wasn’t any footin’. But he left Terry an’ me to pack the dead hoss’s load an’ some other stuff that he couldn’t carry, on a couple of sledges, an’ to fetch them an’ you on by river an’ meet him below. Understand?”

Stub nodded. How his brain did whirl, trying to patch things together! It was as if he had wakened from a dream, and couldn’t yet separate the real from the maybe not.

“We’d best be going on,” Terry Miller warned. “We’re to ketch the cap’n before night, and we’re short of grub.”

So the sledges proceeded by the river trail, while Stub lay and pondered. By the pain now and then in his head, when the sledge jolted, he had struck his scar; but somehow he had a wonderful feeling of relief, there. He was a new boy.

The trail continued as rough as ever. Most of the way the two men, John and Terry, had to pull for all they were worth; either tugging to get their sledges around open water by route of the narrow strips of shore, or else slipping and scurrying upon the snowy ice itself. Steep slopes and high cliffs shut the trail in, as before. The gaps on right and left were icy ravines and canyons that looked to be impassible.

The main party were not sighted, nor any trace of them. Toward dusk, which gathered early, Terry, ahead, halted.

“It beats the Dutch where the cap’n went to,” he complained. “He got out, and he hasn’t managed to get back in, I reckon. Now, what to do?”

“Only thing to do is to camp an’ wait till mornin’,” answered Freegift. “An’ a powerful lonesome, hungry camp it’ll be. But that’s soldierin’.”

“Well, the orders are to ketch him—or to join him farther down, wherever that may be,” said Terry. “But we can’t travel by night, in here. So we’ll have to camp, and foller out our orders to-morrow.”

It was a lonesome camp, and a cold camp, and a hungry camp, here in the dark, frozen depths of the long and silent defile cut by the mysterious river. They munched a few mouthfuls apiece of dried meat; Stub slept the most comfortably, under a blanket upon the sledge; the two men laid underneath a single deer-hide, upon the snow.

They all started on at daybreak. Stub was enough stronger so that he sprang off to lighten the load—even pushed—at the worst places. Indeed, his head was in first-class shape; the scar pained very little. And he had rather settled down to being Jack Pursley again. Only, he wished that he knew just where his father was. Dead? Or alive?

It was slow going, to-day. The river seemed to be getting narrower. Where the current had overflowed and had frozen again, the surface was glary smooth; the craggy shore-line constantly jutted with sudden points and shoulders that forced the sledges out to the middle. The slopes were bare, save for a sprinkling of low bushes and solitary pines, clinging fast to the rocks. Ice glittered where the sun’s faint rays struck.

This afternoon, having worked tremendously, they came out into the lieutenant’s prairie. At least, it might have been the prairie he had reported—a wide flat or bottom where the hills fell back and let the river breathe.

“Hooray! Here’s the place to ketch him,” Freegift cheered. And he called: “See any sign o’ them, Terry?”

“Nope.”

They halted, to scan ahead. All the white expanse was lifeless.

“I swan!” sighed Terry. “Never a sign, the whole day; and now, not a sign here. You’d think this’d be the spot they’d come in at, and wait for a fellow or else leave him word.”

“Yes,” agreed Freegift, “I would that. Do you reckon they’re behind us, mebbe?”

“How’s a man to tell, in such a country?” Terry retorted. “They’re likely tangled up, with half their hosses down, and the loads getting heavier and heavier. But where, who knows? We’ll go on a piece, to finish out the day. We may find ’em lower on, or sign from ’em. If not, we’ll have to camp again, and shiver out another night, with nothing to eat. Eh, Stub? At any rate, orders is orders, and we’re to keep travelling by river until we join ’em. If they’re behind, they’ll discover our tracks, like as not, and send ahead for us.”

“Anyhow, we’re into open goin’. I’m blamed glad o’ that,” declared Freegift. “Hooray for the plains, and Natchitoches!”

“Hooray if you like,” Terry answered back, puffing. “But ’tisn’t any turnpike, you can bet.”

Apparently out of the mountains they were; nevertheless still hard put, for the river wound and wound, treacherous with boulders and air-holes, and the snow-covered banks were heavy with willows and brush and long grass.

After about four miles Terry, in the lead, shouted unpleasant news.

“We might as well quit. We’re running plumb into another set o’ mountains. I can see where the river enters. This is only a pocket.”

Freegift and Stub arrived, and gazed. The mountains closed in again, before; had crossed the trail, and were lined up, waiting. Jagged and gleaming in the low western sunlight, they barred the way.

“There’s no end to ’em,” said Terry, ruefully. “Heigh-hum. ’Pears like the real prairies are a long stint yet. The cap’n will be sore disappointed, if he sees. I don’t think he’s struck here, though. Anyhow, we’ll have to camp—I’m clean tuckered; and to-morrow try once more, for orders is orders, and I’m right certain he’ll find us somewheres, or we’ll find him.”

So they made camp. Freegift wandered out, looking for wood and for trails. He came in.

“I see tracks, Terry. Two men have been along here—white men, I judge; travellin’ down river.”

“Only two, you say?”

“Yes. Fresh tracks, just the same.”

They all looked, and found the fresh tracks of two men pointing eastward.

“I tell you! Those are the doctor and Brown hunting,” Terry proposed. “Wish they’d left some meat. But we may ketch ’em to-morrow. Even tracks are a godsend.”

They three had eaten nothing all day; there was nothing to eat, to-night. To Stub, matters looked rather desperate, again. Empty stomach and empty tracks and empty country, winter-bound, gave one a sort of a hopeless feeling. He and Freegift and Terry trudged and trudged and trudged, and hauled and shoved, and never got anywhere. For all they knew, they might be drawing farther and farther away from the lieutenant. But, as Terry said, “orders were orders.”

“Well, if we ketch the doctor he’ll be mighty interested in that head o’ yourn,” Freegift asserted, to Stub. “He’s been wantin’ to open it up, I heard tell; but mebbe that yaller hoss saved him the trouble.”

“He’ll not thank the hoss,” laughed Terry, grimly. “He’d like to have done the job himself! That’s the doctor of it.”

Stub privately resolved to show the doctor that there was no need of the “job,” now. He felt fine, and he was Jack Pursley.

Nothing occurred during the night; the false prairie of the big pocket remained uninvaded except by themselves. They lingered until about ten o’clock, hoping that the main party might come in.

“No use,” sighed Freegift. “We may be losin’ time; like as not losin’ the doctor. Our orders were, to travel by river till we joined the cap’n.”

With one last survey the two men took up their tow-ropes and, Stub ready to lend a hand when needed, they plodded on.

The tracks of the doctor and John Brown led to the gateway before. The space for the river lessened rapidly. Soon the sides were only prodigious cliffs, straight up and down where they faced upon the river, and hung with gigantic icicles and sheeted with ice masses. The river had dashed from one side to the other, so that the boulders were now spattered with frozen spray.

The tracks of the doctor and John Brown had vanished; being free of foot, they might clamber as they thought best. But the sledges made a different proposition. Sometimes, in the more difficult spots amidst ice, rocks and water, two men and a boy scarcely could budge one.

Higher and higher towered the cliffs, reddish where bare, and streaked with motionless waterfalls. The sky was only a seam. Far aloft, there was sunshine, and the snow even dripped; but down in here all was shade and cold. One’s voice sounded hollow, and echoes answered mockingly.

The dusk commenced to gather before the shine had left the world above. Stub was just about tired out; the sweat had frozen on the clothes of the two men, and their beards also were stiff with frost.

Now they had come to a stopping-place. There was space for only the river. It was crowded so closely and piled upon itself so deeply, and was obliged to flow so swiftly that no ice had formed upon it beyond its very edges. The cliffs rose abruptly on either side, not a pebble-toss apart, leaving no footway.

The trail had ended.

“I cry ‘Enough,’” Terry panted, as the three peered dismayed. “We can’t go on—and we can’t spend the night here, either. We’ll have to backtrack and find some way out.”

“The doctor an’ Brown must ha’ got out somewheres,” Freegift argued. “They never passed here. Let’s search whilst there’s light. If we can fetch out we may yet sight ’em, or the cap’n. An’ failin’ better, we can camp again an’ bile that deer-hide for a tide-me-over. Some sort o’ chawin’ we need bad.”

“Biled deer-hide for supper, then,” Terry answered. “It’ll do to fool our stomicks with. But first we got to get out if we can.”

They turned back, in the gloomy canyon whose walls seemed to be at least half a mile high, to seek a side passage up and out. Freegift was ahead. There were places where the walls had been sundered by gigantic cracks, piled with granite fragments. Freegift had crossed the river, on boulders and ice patches, to explore a crack opposite—and suddenly a shout hailed him.

“Whoo-ee! Hello!”

He gazed quickly amidst his clambering; waved his arm and shouted reply, and hastened over.

“Somebody!” Terry exclaimed. He and Stub ran forward, stumbling. They rounded a shoulder, and joining Freegift saw the lieutenant. In the gloom they knew him by his red cap if by nothing else. He was alone, carrying his gun.

“I’ve been looking for you men,” he greeted. “You passed us, somehow.”

“Yes, sir,” Freegift admitted. “An’ we’ve been lookin’ for you, too, sir. We didn’t know whether you were before or behind.”

“And begging your pardon, sir, we’re mighty glad to see you,” added Terry. “Are the men all behind, the same as yourself, sir?”

“Part of them.” The lieutenant spoke crisply. “The doctor and Brown are still ahead, I think. I haven’t laid eyes on them. You three were next. The rest of the party is split. From the prairie back yonder I detached Baroney and two men to take the horses out, unpacked, and find a road for them. We have lost several animals by falls upon the rocks, and the others were unable to travel farther by river. The remaining eight men are coming on, two by two, each pair with a loaded sledge. I have preceded them, hoping to overtake you. The command is pretty well scattered out, but doing the best it can.” His tired eyes scanned Stub. “How are you, my brave lad?”

“All right, sir. But my name’s Jack Pursley, now. That knock I got made me remember.”

“What!”

“You see, sir,” Freegift explained in haste, and rather as if apologizing for Stub’s answer, “when he come to after that rap on the head he was sort o’ bewildered like; an’ ever since then he’s been claimin’ that he’s a white boy, name o’ Pursley, from Kaintuck, an’ was stole from his father, by the Injuns, up in that very Platte River country where we saw all them camp sign.”

“Oh!” uttered the lieutenant. “You were there? How many of you? All white? Where’s your father? How long ago?”

“About three years, I think,” Stub stammered. “Just we two, sir. We were hunting and trading on the plains, with some Kiowas and Comanches, and the Sioux drove us into the mountains. Then we joined the Utahs, and after a while they stole me. They hit me on the head and I forgot a lot of things—and I don’t know where my father is, sir.”

“Hah! I thought we were the first white men there,” ejaculated the lieutenant. “The first Americans, at least. It’s a pity you didn’t come to before. You might have given us valuable information.”

“He says they found gold in that Platte country, sir,” said Terry.

“Yes? Pshaw! But no matter now. We’ll pursue that subject later. First, we must get out of this canyon. You discovered no passage beyond?”

“No, sir. Never space to set a foot.”

“Have you any food?”

“Had none for two days, sir. We were thinking of biling a deer-hide for our supper.”

“You’re no worse off than the others. The whole column is destitute again, but the men are struggling bravely, scattered as they may be. The doctor and Brown came this way. You haven’t sighted them?”

“No, sir; only their tracks, back a piece.”

“Then they got out, somehow. We must find their trail before dark, and follow it up top, where there’s game. Search well; our comrades behind are depending on us.”

They searched on both sides of the canyon. Stub’s Indian-wise eyes made the discovery—a few scratches by hands and gun-stocks, in a narrow ravine whose slopes were ice sheeted. That was the place.

They all hurried to the sledges, took what they might carry, and clawing, slipping, clinging, commenced to scale the ravine. It was a slow trail, and a danger trail, but it led them out, to a flat, cedar-strewn top, where daylight still lingered.

“The doctor and Brown have been here,” panted the lieutenant. “Here are their tracks.”

They followed the tracks a short distance, and brought up at camp sign. Evidently the doctor and Brown had stopped here, the night before; had killed a deer, too—but there was nothing save a few shreds of hide.

“The birds and beasts have eaten whatever they may have left,” spoke the lieutenant. “Too bad, my lads. However, we’re out, and we’ll make shift some way. Fetch up another load, while I hunt.”

Out he went, with his gun. They managed to bring up another load from the sledges. They heard a gunshot.

“Hooray! Meat for supper, after all.”

But when he returned in the darkness he was empty-handed.

“I wounded a deer, and lost him,” he reported shortly; and he slightly staggered as he sank down for a moment. “We can do no more to-night. We’ll melt snow for drinking purposes; but the deer-hide is likely to make us ill, in our present condition. We’ll keep it, and to-morrow we’ll have better luck.”

So with a fire and melted snow they passed the night. Nobody else arrived. The doctor and Brown seemed to be a day’s march ahead; Baroney and Hugh Menaugh and Bill Gordon were wandering with the horses through this broken high country; and the other eight were toiling as best they could, with the sledges, in separate pairs, seeking a way out also.

The lieutenant started again, early in the morning, to find meat for breakfast. They went down into the canyon, to get the rest of the loads, and the sledges—and how they managed, with their legs so weary and their stomachs so empty, Stub scarcely knew.

They heard the lieutenant shoot several times, in the distance; this helped them. He rarely missed. But he came into camp with nothing, and with his gun broken off at the breech—had wounded deer, had discovered that his gun was bent and shot crooked—then had fallen and disabled it completely.

He was exhausted—so were the others; yet he did not give up. He rested only a minute. Then he grabbed up the gun that had been stowed among the baggage. It was only a double-barreled shotgun, but had to do.

“I’ll try again, with this,” he said. “You can go no further; I see that. Keep good heart, my lads, and be sure that I’ll return at best speed with the very first meat I secure.”

“Yes, sir. We’ll wait, sir. And good luck to ye,” answered Terry.

Sitting numb and lax beside the baggage, they watched the lieutenant go stumbling and swerving among the cedars, until he had disappeared.

“A great-hearted little officer,” Freegift remarked. “Myself, I couldn’t take another step. I’m clean petered out, at last. But him—away he goes, never askin’ a rest.”

“And he’ll be back. You can depend on that,” put in Terry. “Yes. He’ll not be thinking of himself. He’s thinking mainly on his men. He’ll be back with the meat, before he eats a bite.”

They heard nothing. The long day dragged; sometimes they dozed—they rarely moved and they rarely spoke; they only waited. Up here it was very quiet, with a few screaming jays fluttering through the low trees. Stub caught himself nodding and dreaming: saw strange objects, grasped at meat, and woke before he could eat. He wondered if Freegift and Terry saw the same.

The sun set, the air grew colder.

“Another night,” Freegift groaned. “He’s not comin’. Now what if he’s layin’ out somewheres, done up!”

“If he’s still alive he’s on his feet, and seeking help for us,” Terry asserted. “He said to wait and he’d come. You can depend on him. Orders be orders. He found us, below, and he’ll find us here.”

“We’ve got to suck deer-hide, then,” announced Freegift. “It may carry us over.”

They managed to arouse themselves; half boiled strips of deer-hide in a kettle of snow-water, and chewed at the hairy, slimy stuff. But they couldn’t swallow it.

“Oh, my!” Terry sighed. “’Tain’t soup nor meat, nor what I’d call soldiers’ fare at all. We had hard times before, up the Mississippi with the left’nant; but we didn’t set teeth to this. What’d I ever enlist for?”

“The more I don’t know,” answered Freegift. “But stow one good meal in us an’ we’d enlist over again, to foller the cap’n on another trip.”

Terry tried to grin.

“I guess you’re right. But, oh my! Down the Red River, heading for white man’s country, is it? Then where are we? Nowhere at all, and like to stay.”

Through the gnarled cedars beside the mighty canyon the shadows deepened. The mountain ridges and peaks, near and far, surrounding the lone flat, swiftly lost their daytime tints as the rising tide of night flowed higher and higher. And soon it was dark again.

Now they must wait for another morning as well as for the lieutenant.

They had already sickened of the deer-hide, and could not touch it again. So the morning was breakfastless. The sun had been up only a few minutes, and Stub was drowsing in a kind of stupor, when he heard Freegift exclaim:

“He’s comin’, boys! Here comes the cap’n! Say! Don’t I see him—or not?”

“There’s two of ’em!” cried Terry. “He’s found company. No! That ain’t the cap’n. It’s somebody else. But our men, anyhow.”

Two men afoot were hastening in through the cedars, along the canyon rim. They carried packages—meat! They were Hugh Menaugh and Bill Gordon. Hooray!

“Hello to you!”

“Yes, we’re still here,” replied Terry. “And if you’ve fetched anything to eat, out with it quick. Where’s the cap’n? Did you see him?”

Hugh and Bill busied themselves.

“Yes, we met up with him last evenin’, below, down river. He hadn’t come back to you, ’cause he hadn’t killed anything. But Baroney and us were packin’ buffalo meat and deer meat both, and he sent us two out to find you first thing this mornin’, soon as ’twas light enough to s’arch. After you’ve fed, we’ll help you on to camp.”

“Who else is there?”

“Just the cap’n and Baroney, but they’re expectin’ the doctor and Brown. Them two are somewheres in the neighborhood. The cap’n fired a gun as signal to ’em. We’ll have to look for the other fellers.”

“What kind of a camp, an’ whereabouts?” Freegift asked, as he and Terry and Stub greedily munched.

“Oh, a good camp, in the open, not fur from the river.”

Hugh and Bill acted oddly—with manner mysterious as if they were keeping something back. After the meal, Hugh opened up.

“Now that you’ve eaten, guess I’ll tell you what’s happened,” he blurted. “You’ll know it, anyhow.”

“Anybody dead? Not the cap’n!”

“No. Nothing like that. But this ain’t the river.”

“Ain’t the Red River?”

“Nope.”

The three stared, dazed.

“What river might it be, then?” gasped Freegift.

“The Arkansaw ag’in. An’ camp’s located on that very same spot in the dry valley where we struck north last December, scarce a month ago!”[G]

“It’s certainly hard on the little cap’n,” Bill added. “Yesterday, his worst day of all, when near dead he made out and espied the landmarks, was his birthday, too.”

“What’s the date?” Terry queried. “I’ve forgot.”

“Fifth o’ January. To-day’s the sixth. It was December 10 when we camped yonder before.”