XX

STUB REACHES END O’ TRAIL

“Santa Fe! The city of Santa Fe! Behold!”

Those were the cries adown the delighted column. Here they were, at last; but this was the evening of the fifth day since leaving the camp, and the distance was more than one hundred and sixty miles. The two spies, who had said that Santa Fe was only two days’ journey from the stockade, had lied.

The first stage of the trip had been very cold, in deep snow. Then, on the third day, or March 1, they had emerged into a country of warmth and grass and buds, at the first of the Mexican settlements—a little town named Aqua Caliente or Warm Springs. Hooray!

They all, the Americans, viewed it curiously. The houses were low and one-story, of yellowish mud, with flat roofs; grouped close together so that they made an open square in the middle of the town and their rears formed a bare wall on the four sides.

“’Tis like a big brick-kiln, by jinks,” remarked Freegift. “Now I wonder do they build this way for fear o’ the Injuns?”

The people here numbered about five hundred—mainly Indians themselves, but tame Indians, Pueblos who lived in houses, with a mingling of Mexican blood. From the house-tops they welcomed the column; and thronging to meet it they brought out food and other gifts for the strangers. That night there was a dance, with the Americans as guests of honor.

“If this is the way they treat prisoners,” the men grinned, “sure, though some of us can’t shake our feet yet, we’re agreeable to the good intentions.”

The same treatment had occurred all the way down along the Rio Grande del Norte, through a succession of the flat mud villages. There had been feasting, dancing, and at every stop the old women and old men had taken the Americans into the houses and dressed their frozen feet.

“This feet-washin’ and food-givin’ makes a feller think on Bible times,” William Gordon asserted. “The pity is, that we didn’t ketch up with that Spanish column that was lookin’ for us and gone right home with ’em for a friendly visit. They’d likely have put us on the Red River and have saved us our trouble.”

“Well, we ain’t turned loose yet, remember,” counseled Hugh Menaugh. “From what I l’arn, the Melgares column didn’t aim to entertain us with anything more’n a fight. But now we’re nicely done, without fightin’.”

“Yes, this here politeness may be only a little celebration,” Alex mused. “It’s cheap. For me, I’d prefer a dust or two, to keep us in trim.”

There had been one bit of trouble, which had proved that the lieutenant, also, was not to be bamboozled. In the evening, at the village named San Juan, or St. John, the men and Stub were together in a large room assigned to them, when the lieutenant hastily entered. He had been dining at the priest’s house, with Lieutenant Bartholomew; but now a stranger accompanied him—a small, dark, sharp-faced man.

The lieutenant seemed angry.

“Shut the door and bar it,” he ordered, of John Brown. Then he turned on the stranger. “We will settle our matters here,” he rapped, in French; and explained, to the men: “This fellow is a spy, from the governor. He has been dogging me and asking questions in poor English all the way from the priest’s house. I have requested him to speak in his own language, which is French, but he understands English and would pretend that he is a prisoner to the Spanish—‘like ourselves,’ he alleges. I have informed him that we have committed no crime, are not prisoners, and fear nothing. We are free Americans. As for you,” he continued, to the man, roundly, “I know you to be only a miserable spy, hired by the governor in hopes that you will win my sympathy and get me to betray secrets. I have nothing to reveal. But it is in my power to punish such scoundrels as you”—here the lieutenant drew his sword—“and if you now make the least resistance I will use the sabre that I have in my hand.”

“Let us fix him, sir,” cried Hugh, Freegift, and the others. “We’ll pay him an’ save the governor the trouble.”

They crowded forward. The dark man’s legs gave out under him and down he flopped, to his knees.

“No, señores! For the love of God don’t kill me. I will confess all.” He was so frightened that his stammering English might scarcely be understood. “His Excellency the governor ordered me to ask many questions. That is true. And it is true that I am no prisoner. I am a resident of Santa Fe, and well treated. The governor said that if I pretended hatred of the country you would be glad of my help. I see now that you are honest men.”

“What is your name?” the lieutenant demanded.

“Baptiste Lelande, señor, at your service.”

“You can be of no service to me save by getting out of my sight,” retorted the lieutenant, scornfully, and clapping his sword back into its sheath. “You are a thief, and doubtless depend upon the governor for your safety. Tell His Excellency that the next time he employs spies upon us he should choose those of more skill and sense, but that I question whether he can find any such, to do that kind of work. Now begone.”

John Brown opened the door. The man scuttled out.

“My lads,” spoke the lieutenant, when the door had been closed again, “this is the second time that I have been approached by spies, on the march. On the first occasion I assumed to yield, and contented the rascal by giving into his keeping a leaf or two copied from my journal—which in fact merely recounted the truth as to our number and our setting forth from the Missouri River. The fellow could not read, and is treasuring the paper, for the eyes of the governor. If I am to be plagued this way, I fear that my baggage or person may be searched, and my records obtained by our long toil be stolen. Accordingly I shall trust in you, knowing that you will not fail me. I have decided to distribute my important papers among you, that you may carry them on your persons, out of sight.”

So he did.

“They’ll be ready for you when you want ’em, cap’n, sir,” Freegift promised, as the men stowed the papers underneath their shirts. “If the Spanish want ’em, they’ll have to take our skins at the same time.”

“That they will,” was the chorus.

“To the boy here I consign the most important article of all,” pursued the lieutenant, “because he is the least likely to be molested. It is my journal of the whole trip. If that were lost, much of our labors would have been thrown away. I can rely on you to keep it safe, Stub?”

“Yes, sir.” And Stub also stowed away his charge—a thin book with stained red covers, in which the lieutenant had so frequently written, at night.

“We will arrive at Santa Fe to-morrow, lads,” the lieutenant had warned. “And if my baggage is subjected to a search by order of the governor, I shall feel safe regarding my papers.”

Presently he left.

“Lalande, the nincompoop was, was he?” remarked Jake Carter. “Well, he got his come-upments. But ain’t he the same that the doctor was lookin’ for—the sly one who skipped off with a trader’s goods?”

“So what more could be expected, than dirty work, from the likes!” Hugh proposed.

The lieutenant fared so heartily at the priest’s house that this night he was ill. In the morning, which was that of March 3, they all had ridden on southward, led by him and by the pleasant Don Lieutenant Bartholomew. They had passed through several more villages, one resembling another; and in the sunset, after crossing a high mesa or flat tableland covered with cedars, at the edge they had emerged into view of Santa Fe, below.

“Santa Fe! La ciudad muy grande (The great city)! Mira (See)!”

Those were the urgent exclamations from the dragoons and militia.

“‘Great city,’ they say?” Hugh uttered, to Stub. “Huh! Faith, it looks like a fleet o’ flatboats, left dry an’ waitin’ for a spring rise!”

It was larger than the other villages or towns, and lay along both flanks of a creek. There were two churches, one with two round-topped steeples; but all the other buildings were low and flat-roofed and ugly, ranged upon three or four narrow crooked streets. At this side of the town there appeared to be the usual square, surrounded by the mud buildings. Yes, the two-steepled church fronted upon it.

As they rode down from the mesa, by the road that they had been following, the town seemed to wake up. They could hear shouting, and might see people running afoot and galloping horseback, making for the square.

A bevy of young men, gaily dressed, raced, ahorse, to meet the column. The whole town evidently knew that the Americans were coming. The square was filled with excited men, women and children, all chattering and staring.

Lieutenant Bartholomew cleared the way through them, and halted in front of a very long, low building, with a porch supported on a row of posts made of small logs, and facing the square, opposite the church. He swung off. The dragoons and militia kept the crowd back.

Lieutenant Pike, in his old clothes, swung off.

“Dismount!” he called. “We are to enter here, lads. Bear yourselves boldly. We are American soldiers, and have nothing to fear.”

He strode on, firm and erect, following the guidance of Lieutenant Bartholomew.

“Keep together,” Freegift cautioned; and the men pushed after, trying not to limp, and to carry their army muskets easily. Stub brought up the tail of the little procession. He, too, was an American, and proud of it, no matter how they all looked, without hats, in rags and moccasins, the hair of heads and faces long.

They entered the long-fronted building. The doorway was a full four feet thick. The interior was gloomy, lighted by small deep-set windows with dirty panes. There was a series of square, low-ceilinged rooms—“’Tis like a dungeon, eh?” Freegift flung back—but the earth floors were strewn with the pelts of buffalo, bear, panther, what-not.

They were halted in a larger room, with barred windows and no outside door. Lieutenant Bartholomew bowed to Lieutenant Pike, and left. Against the walls there were several low couches, covered with furs and gay blankets, for seats. So they sat down, and the men stared about.

“Whereabouts in here are we, I wonder,” John Brown proposed.

“Did ye see them strings o’ tanned Injun ears hangin’ acrost the front winders!” remarked Hugh Menaugh.

“Sure, we’d never find way out by ourselves,” declared Alex Roy. “It’s a crookeder trail than the one to the Red River.”

The lieutenant briefly smiled; but he sat anxiously.

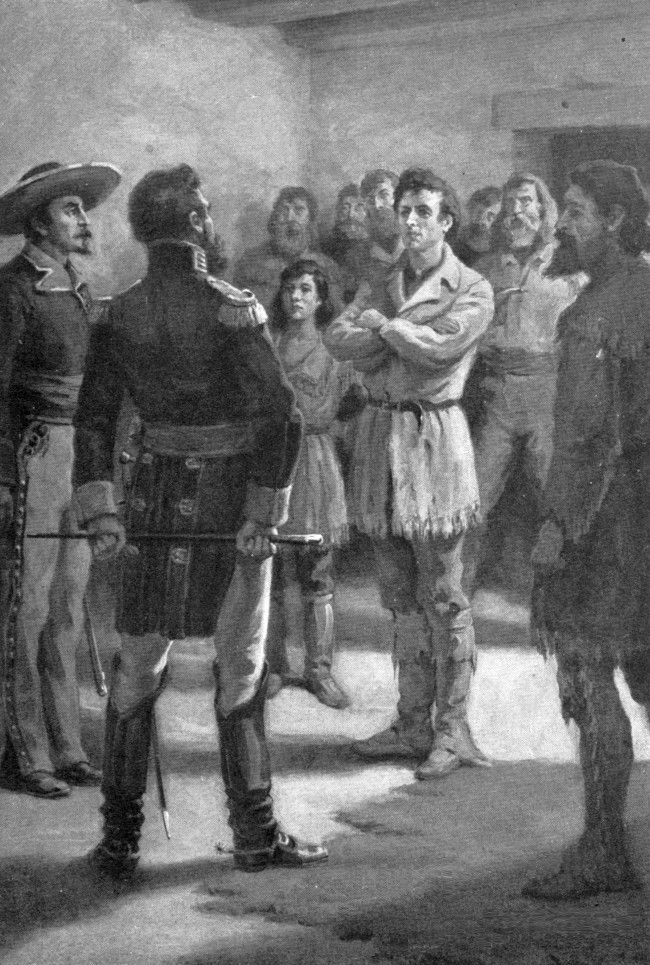

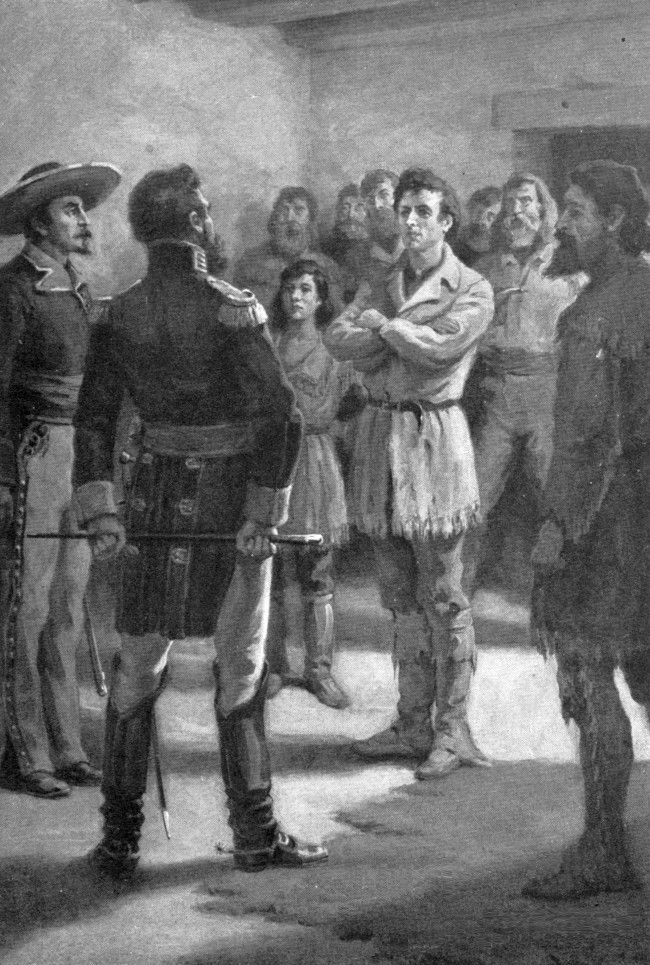

Lieutenant Bartholomew suddenly returned; close behind him a large, heavy-set, swarthy, hard-faced man, of sharp black eyes, and dressed in a much decorated uniform. Lieutenant Pike hastily arose, at attention; they all rose.

“His Excellency Don Joaquin del Real Alencaster, Governor of the Province of New Mexico,” Lieutenant Bartholomew announced. “I have the honor to present Lieutenant Don Mungo-Meri-Paike, of the American army.”

Lieutenant Pike bowed; the governor bowed, and spoke at once, in French.

“You command here?”

“Yes, sir.” The lieutenant answered just as quickly.

“Do you speak French?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You come to reconnoiter our country, do you?”

“I marched to reconnoiter our own,” replied Lieutenant Pike.

“In what character are you?”

“In my proper character, sir: an officer of the United States army.”

“IN MY PROPER CHARACTER, SIR: AN OFFICER OF THE UNITED STATES ARMY”

“And the man Robinson—is he attached to your party?”

“No.” The governor’s voice had been brusque, and the lieutenant was beginning to flush. But it was true that the doctor was only an independent volunteer.

“Do you know him?”

“Yes. He is from St. Louis.”

“How many men have you?”

“I had fifteen.” And this also was true, when counting the deserter Kennerman.

“And this Robinson makes sixteen?” insisted the governor.

“I have already told your Excellency that he does not belong to my party,” the lieutenant retorted. “I shall answer no more enquiries on the subject.”

“When did you leave St. Louis?”

“July 15.”

“I think you marched in June.”

“No, sir.”

“Very well,” snapped the governor. “Return with Don Bartholomew to his house, and come here again at seven o’clock and bring your papers with you.”

He shortly bowed, whirled on his heels and left. The lieutenant bit his lips, striving to hold his temper. Lieutenant Bartholomew appeared distressed.

“A thousand apologies, Don Lieutenant,” he proffered. “His Excellency is in bad humor; but never mind. You are to be my guest. Your men will be quartered in the barracks. Please follow me.”

They filed out, through the rooms, into daylight again.

“A sergeant will show your men, señor. They are free to go where they please, in the city,” said Lieutenant Bartholomew. “My own house is at your service.”

“Go with Lieutenant Bartholomew’s sergeant, lads,” Lieutenant Pike directed. “Guard your tongues and actions and remember your duty to your Government.”

Beckoning with a flash of white teeth underneath his ferocious moustache the dragoon sergeant took them to the barracks. These were another long building on the right of the first building, fronting upon the west side of the square and protected by a wall with a court inside.

At a sign from the sergeant they stacked their muskets and hung their pistols, in the court. Then they were led in to supper.

“Sure, we’re goin’ to be comfortable,” Freegift uttered, glancing around as they ate. “The food is mighty warmin’—what you call the seasonin’? Pepper, ain’t it, same as we got, above? Yes.”

“Did you hear what they call that other buildin’, where we were took first?” asked Jake Carter, of Stub.

“The Palace of the Governors, the soldiers said.”

“Palace!” Jake snorted. “It’s more like the keep of a bomb-proof fort. I’ve dreamed of palaces, but never such a one. There’s nothin’ for a governor to be so high and uppish about.”

“The cap’n gave him tit for tat, all right,” asserted William Gordon. “We’ve got a verse or two of Yankee Doodle in us yet!”

They finished supper and shoved back their cowhide benches.

“We’re to go where we plaze, ain’t it?” queried Hugh. “So long as we keep bounds? Well, I’m for seein’ the town whilst I can.”

“We’re with you, old hoss,” they cried, and trooped into the court.

First thing, they found that their guns had vanished.

Freegift scratched his shaggy head.

“Now, a pretty trick. We’re disarmed. They come it over us proper, I say.”

Spanish soldiers were passing to and fro. Some stared, some laughed, but nobody offered an explanation or seemed to understand the questions.

“That wasn’t in the bargain, was it?” Alex Roy demanded. “The cap’n’ll have a word or two of the right kind ready, when he learns. Anyhow, we’ll soon find out whether we’re prisoners as well. Come on.”

The gate at the entrance to the court was open. The guard there did not stop them. They had scarcely stepped out, to the square, when loitering soldiers and civilians, chatting with women enveloped in black shawls, welcomed them in Spanish and beckoned to them, and acted eager to show them around.

“‘Buenas noches,’ is it? ‘Good evenin’ to ye,’” spoke Freegift. “I expect there’ll be no harm in loosenin’ up a bit. So fare as you like, boys, an’ have a care. I’m off. Who’s with me?”

They trooped gaily away, escorted by their new Santa Fean friends. Stub stuck to Freegift, for a time; but every little while the men had to stop, and drink wine offered to them at the shops and even at the houses near by; so, tiring of this, he fell behind, to make the rounds on his own account and see what he chose to see.

He was crossing the bare, hard-baked square, or plaza as they called it, to take another look at the strings of Indian ears festooned on the front of the Governor’s Palace, when through the gathering dusk somebody hailed him.

“Hi! Muchacho! Aqui! (Hi! Boy! Here!)”

It was Lieutenant Bartholomew, summoning him toward the barracks. The lieutenant met him.

“Habla Español (You speak Spanish)?”

“Very little,” Stub answered.

“Bien (Good).” And the lieutenant continued eagerly. “Como se llama Ud. en Americano (What is your name in American)?”

“Me llamo Jack Pursley (My name is Jack Pursley), señor.”

“Si, si! Bien! Muy bien! (Yes, yes! Good! Very good!)” exclaimed the lieutenant. “Ven conmigo, pues (Come with me, then).”

On he went, at such a pace that Stub, wondering, had hard work keeping up with him. They made a number of twists and turns through the crooked, darkened streets, and the lieutenant stopped before a door set in the mud wall of a house flush with the street itself. He opened, and entered—Stub on his heels. They passed down a narrow verandah, in a court, entered another door——

The room was lighted with two candles. It had no seats except a couple of blanket-covered couches against its wall; a colored picture or two of the saints hung on the bare walls. A man had sprung up. He was a tall, full-bearded man—an American even though his clothes were Spanish.

He gazed upon Stub; Stub gaped at him.

“It is the boy,” panted Lieutenant Bartholomew. “Bien?”

“Jack!” shouted the man.

“My dad!” Stub blurted.

They charged each other, and hugged.

“Good! Good!” exclaimed the lieutenant, dancing delighted. Several women rushed in, to peer and ask questions.

“Boy, boy!” uttered Jack’s father, holding him off to look at him again. “I thought never to see you, after the Utes got you. They took you somewhere—I couldn’t find out; and finally they fetched me down to Santa Fe, and here I’ve been near two years, carpentering.”

“Couldn’t you get away?”

“No. They won’t let me. And now I’m mighty glad.”

“Well, I’m here, too,” laughed Stub. “And I guess I’ll stay; but I’ll have to ask Lieutenant Pike.”

“He’s gone to the palace, to talk with the governor again. You and I’ll talk with each other. I came especially to see him; thought maybe he might help me, and I hoped to talk with one of his kind. American blood is powerful scarce in Santa Fe. There’s only one simon-pure Yankee, except myself. He’s Sol Colly; used to be a sergeant in the army and was captured six years ago along with the rest of a party that invaded Texas. But he doesn’t live here. A Frenchman or two, here from the States, don’t count. My, my, it’s good to speak English and to hear it. As soon as the lieutenant learnt my name he remembered about you; but he couldn’t wait, so Don Bartholomew went to find you. Now you’ll go home with me, where we can be snug and private.”

He spoke in Spanish to Lieutenant Bartholomew, who nodded.

“Certainly, certainly, señor. Until to-morrow morning.”

And Jack gladly marched home hand-in-hand with his father, James Pursley, of Kentucky, the discoverer of gold in Colorado, and the first American resident in Santa Fe.