CHAPTER IV

THE work of repairing the damage caused by the freshet was pushed and by the end of the week a temporary bridge had been constructed over the creek and the canal below the house, enabling foot-passengers from the mountain to cross over to the village.

Mr. De Vere’s letter declining to sell was forwarded to Mills and the mortgage transferred to Mr. Genung. The latter was very anxious that Hernando should prospect on Mr. De Vere’s mining claim so, to satisfy him, Mr. De Vere agreed to accompany them on an expedition to it as soon as the weather would permit. Accordingly they started up the mountain back of the house one morning in the following week. They followed the path to the maple bush for some distance, then, turning to the east, climbed over rocks and broken trees to Point Wawanda and then struck into a gully just behind it. Many rivulets flowed down the mountain above, but one in particular, after a swift rush from the very summit, dropped down into the earth under Point Wawanda. Placing his ear to the earth Hernando could hear a roar as of underground waters and knew that they must have passed through some cavern or cleft far down in the mountain. Carefully taking his bearings, they were found to accord exactly with the description of the marks and locations described by Benny. Hernando felt assured that somewhere near was the cave and one of considerable extent. Directly in front of him rose a cliff over one hundred feet in height. Scaling this, the young man looked westward towards the Laurels. “Ah,” he said, aloud, holding his nose at a crevice in the rocks, “one mystery is explained to my satisfaction: gas. So, ‘no one that has ever seen it has been able in daylight to find whence it arose,’” he laughed. “If all instances were as harmless as this one what a delightful place to live in this dreary old world would be.” He descended to his former position for a closer inspection of the cliff.

Suddenly his experienced eye was attracted by a fissure in the rocks composing the entire eastern side of Wawanda and which ran almost to the top. Hernando approached it and brushing aside the snow he forced his body through an opening just large enough to admit it. The crevice was full of snow but, with much labor, he dug his way along and found this was the entrance to a second passage-way, which he also entered. Further progress was barred by a heap of rocks, but these were loose and, removing them, an almost circular opening was disclosed. He lighted a candle and crawling on hands and knees finally emerged into a sort of cave. Long and loud he shouted to the waiting men outside and at last a faint “Hello” proclaimed that these portly gentlemen were squeezing their way through, and after a long time they stood beside Hernando, panting and perspiring. As soon as they recovered their breath, they proceeded to explore this mysterious cavern.

“Look here!” said Hernando, who, with a deft stroke of his hammer, had shivered the rock, disclosing a dull yellow surface. “Gold!” they exclaimed, looking excitedly into each other’s faces.

“Yes,” Hernando continued calmly. “The whole inner surface of these rocks is full of gold. Others have been here before us too. Some one has struck a pocket, and recently. Look, here is a cavity which seems to have been dug out.”

Mills’s offer flashed through De Vere’s mind, but he dismissed the thought as unworthy, and turned to listen to a sound of rumbling which seemed to come from the bowels of the earth. Hernando heard it too, and removing a heap of rubbish from one corner made his way through a hole, but quickly reappeared saying he had better be secured by a rope as these underground passages were treacherous. Mr. De Vere threw a loop about his waist, securely fastened the other end, and held back the slack in his hand ready to be guided by signals, and Hernando again disappeared from view down a slanting rock worn smooth by the action of water that at one time must have flowed over it, but which now issued from under a slimy boulder some feet lower down at the opposite side. Sliding and falling alternately he at last landed on a sort of platform about ten feet wide and running along the brink of a pit which seemed bottomless. The dim light from his miner’s candle cast weird shadows on the black rocks over whose sides snake-like streams crept stealthily down. Hernando shivered and turned to leave the spot, when his attention was attracted by an object at the further end of the platform. There lay what appeared to be an image of stone. He drew nearer, and kneeling down looked long and carefully down at it. Unmistakably it was the petrified body of an Indian. Those features could belong to no other race. The eyes and hair, one foot and three fingers were gone; but otherwise, the body seemed to be in a state of perfect preservation,—to have been literally turned into stone. Of course all remnants of clothing had disappeared, though even the remaining toe and finger-nails were perfect. But the ears! did human beings ever possess such appendages? The lobes were so elongated as to nearly rest on the shoulders.

This man must have been a giant, for the body measured nearly seven feet. Hernando attempted to roll it over but found this impossible, for besides its great weight, the image was covered with slime, and during his efforts one ear was broken off. This Hernando put into his pocket.

The heavy air oppressed him, and so absorbed had he been in his examination that he had not noticed how near the edge of the platform he was, until on attempting to rise his feet slipped from under him. His cap with the candle rolled down into the pit, and in total darkness he hung suspended over that yawning abyss.

Almost overpowered by the heavy air, he had barely strength enough left to guide the rope which, from the violent jerk it gave, warned those above of danger.

Gasping for breath, he was pulled up to where the fresher air soon revived him and he was then enabled to relate his discovery.

The enormous petrified ear must undoubtedly have belonged to “Old Ninety-Nine.”

Palæontologists assert and prove the petrifying properties of these mountain streams. Undoubtedly the lower cave had once been the channel of the stream which now rumbled far below, and nature in the throes of growing-pains had opened a new channel.

How “Old Ninety-Nine” came to be there, or met his death, must remain a mystery, but his cave was at last discovered.

Completely restored, Hernando hastened to procure assistance in bringing the body out, and after travelling down the mountain toward the house for a short distance he met Reuben and a sturdy wood-chopper by the name of Mike McGavitt, on their way to the woods. To them he unfolded his plans and they readily consented to assist him. Reuben volunteered to bring whatever articles were needed. These were rubbers for all the party, plenty of stout rope and a plank. Reuben comprehended fully what they were needed for, and in little less than half an hour returned with the things, and they all hastened back to the cave, where De Vere and Genung were strolling about the entrance. Hernando led into the cave followed by the others. Inside, Hernando, Reuben and Mike divested themselves of their boots and securely strapping on their feet a pair of rubbers to prevent slipping, were successfully lowered to the platform on which lay all that was left of “Old Ninety-Nine.” Mike came last, and as he slid down the incline, clutching the rope, he called, “Schteady, me byes, schteady!” He crept along the shelf, averting his eyes from the pit. Next the plank was lowered, and it required the united efforts of all three to roll the body upon it. At last it was securely fastened, and Reuben was pulled up to assist the other two in hauling the body to the surface. “Kape aninst the wall, mind your noose!” Mike shouted, and though his teeth chattered with terror, he winked at Hernando and said, “Phat’s the program, me bye? I’m wid ye phatever it do be, but it’s a howlin’ boost!”

They pushed the plank along carefully and were about to signal for a hoist line when Mike lunged backward and would have fallen over the precipice but for Hernando’s timely assistance. The plank was not yet attached to any thing but the rope by which it had been lowered and Mike’s frantic clutchings sent it over the brink. Down, down, down it went, crashing against first one side and then another. At last a faint splash proclaimed that the terrific leap was over and once more “Old Ninety-Nine’s” body had eluded human gaze. The next discoverer will find it minus one ear. Learned men will account for this on scientific principles; they will analyze petrifying fluids and tell us why some portions of the body are affected and others not; but the fascination which clings so tenaciously to the memory of “Old Ninety-Nine” will endure as long as the Shawangunks, and each succeeding generation will continue to be told that “Every seven years a bright light like a candle rises at twelve o’clock over the mine and disappears in the clouds; but no one who has ever seen it has been able by daylight to find from whence it came.”

The belief of the Indians that after they had endured their punishment for sins committed, the Great Spirit would restore to them their hunting-grounds caused them to keep their mines a secret. “Old Ninety-Nine” is one no longer, and let us hope that in richer mines and fairer hunting-grounds than he dreamed of, he is beyond the treachery of his white brother—beyond injustice and unfair dealing, where his great Manitou does not offer him the cup of good-will in the form of an unknown intoxicant as did Henry Hudson when planning the seizure of the land of his forefathers.

Hernando signalled for them to be drawn up and the news of the accident was duly reported.

“After all,” said Mr. De Vere, “it is better so. His body would simply have been an object of curiosity. Let the waters which transformed his flesh into stone receive it again.”

Mike looked relieved. “Shure, Schquire is after schpakin’ the truth. So help me, God, niver agin will I schpile the works of God Almighty!” he said.

Mr. Genung was inclined to be provoked, but Hernando explained the exceedingly dangerous position and how fortunate Mike had been to escape with his life, and somewhat ashamed, he asked what was to be done next.

“Put in a blast,” replied Hernando.

Silently they emerged from the cave and followed Hernando around the eastern side of Wawanda where the fissure was through which they had entered. Excavations were begun in earnest and a heavy charge put in. The report which followed must have startled the good people of Nootwyck. It tore a great piece out of the eastern side of Wawanda and when the smoke cleared Hernando was almost beside himself with joy at the result of the explosion. Like the cave, the whole inner surface was full of bits of gold and some spongy masses intermixed with leaves of yellow metal. Hernando picked some of the latter off with the point of his jack-knife and placing it in Mr. De Vere’s hand, said, in the tone of a seasoned miner, “You have struck it rich, Mr. De Vere, and I congratulate you. It may not run far like that, but the chances are that it will. I never saw anything equal to it. Point Wawanda is literally filled with gold veins. That is the lode cropping out nearly to the top.”

Stepping up to the young man whose eyes beamed with such unselfish pleasure, Mr. De Vere placed his hands on his shoulders and said: “Will you accept the position of superintendent of the Hernando Mine?”

“I will gladly accept the position, but would prefer another name.”

“What name is more appropriate than the name of its discoverer?” replied Mr. De Vere warmly.

“None; but who is the discoverer?”

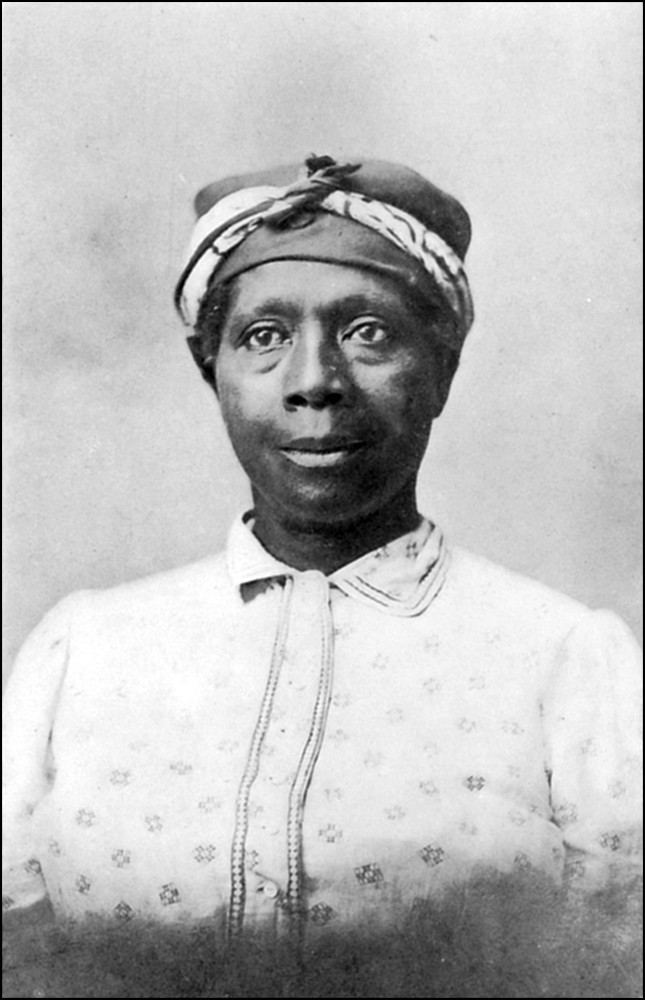

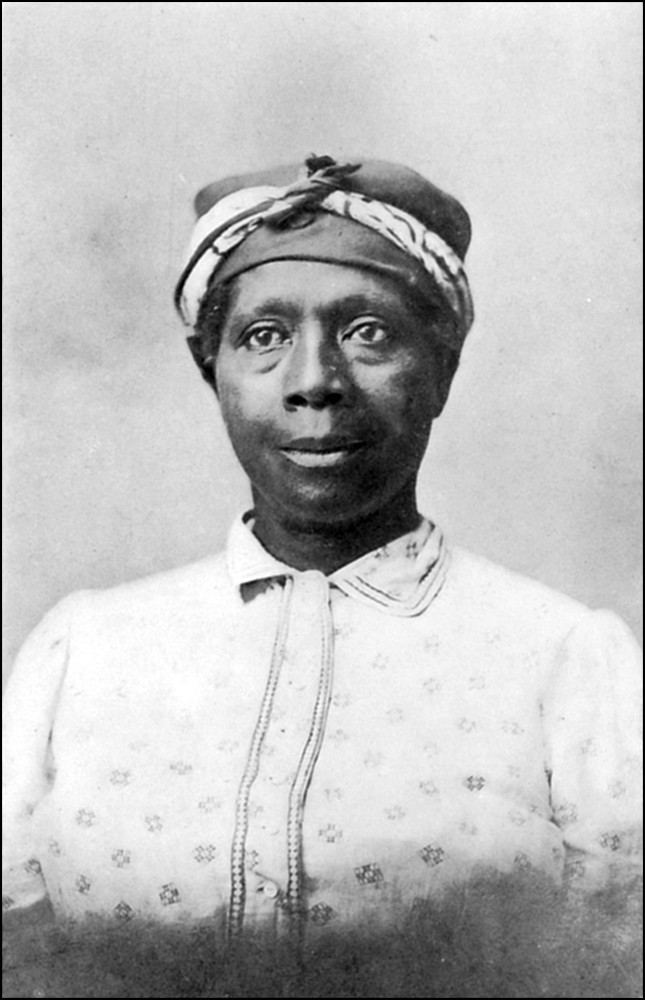

Margaret

Mr. De Vere was silent for a moment and Hernando continued, “Pardon me for suggesting, but much as I appreciate your wish to perpetuate my name, it would give me far more pleasure were it named after ‘Old Ninety-Nine.’”

“Old Ninety-Nine it is then!” they all responded with a shout.

“Ah! Hernando,” said his uncle, “you know paying dirt when you see it. It is born in you.”

His disinterested efforts were appreciated. It meant untold wealth to the owner—wealth expended in helping his fellow-beings—work for hundreds and hundreds of idle miners, comfort for their families, and the transformation of the slumbering village below into a great city.

It was nearly night and the three had eaten nothing since breakfast, so Mr. De Vere’s invitation to supper was readily accepted.

The family had grown anxious at their long absence and the tired prospectors were warmly received. A good bath refreshed them greatly, and they were ready to do justice to Margaret’s fried chicken and puffy hot biscuits.

Mr. Genung was apparently intent on dissecting a chicken leg, but his mind was thousands of miles away. In far-off Nevada another scene had been enacted which this one brought anew to his memory. His younger brother, so like Hernando, had also opened up a mine of untold richness. He also dreamed of founding a mighty city and leaving behind him a name which would go down in history. Did his dreams materialize? How would his name appear on the pages of history, and would the volume be savory reading? Glancing across the table his eyes met Hernando’s, full of bitterness. The absolute misery he saw pictured there softened even the stern features of Andrew Genung.

Eletheer, who had been a silent witness of this thought transference, saw the far-away look in Mr. Genung’s eyes and her heart ached with pity for Hernando. Some great sorrow must be buried in his past, for nothing less could cause those blue eyes to become suddenly black and bring that look of mute suffering into them. From that moment, Eletheer was his sworn friend, and this conclusion once reached was final. She said nothing, however, but talked gaily of their prospects and laughingly asked Mr. Genung what he would do for milkweed greens when the “Island” was all settled.

“You and Mary must turn your attention to agriculture and cultivate them,” he replied.

“Our old camping-grounds will all be spoiled,” she said with mock gravity. “Hunting arbutus, gathering bittersweet berries and picking huckleberries will be but a memory.”

“And you will be a great lady with suitors by the score,” laughed Celeste.

“My suitor has long been accepted,” Eletheer returned gravely.

“Indeed,” said Mr. Genung in some surprise, “if his name is not a secret I should like to know it.”

“Mary is in my confidence,” she answered, “and, like me, has chosen her life-work.”

Mr. Genung eyed her curiously. His own daughter, just about Eletheer’s age, was not a girl to have secrets from her parents.

“This is all nonsense,” Eletheer said hotly. “Mary is fitting herself for a professorship and I intend to become a trained nurse. Granny and Reuben are teaching me now.”

“Well, my dear,” said Mr. Genung, “I trust you both may find a suitable field for your talents in our own beautiful valley.”

Hernando’s cheeks were unusually pale, and after supper as they all followed Mr. De Vere into the library, Granny saw this and remarked on it, but he only laughed and said he felt perfectly well but a little tired.

The mine was discussed in all its bearings, and they decided that Hernando had better spend the night at Mr. De Vere’s so as to be near the field of operations in the morning.

“You look exhausted anyway,” said Mr. De Vere. “Think of the time you spent in that damp, foul hole after all your exertions in gaining access to it.”

Mr. Genung left after making an appointment at Mr. De Vere’s office the next morning to complete arrangements for working the mine, and soon after the family retired, but before Granny sought her bed, she instructed Eletheer in the art of preparing a bowl of boneset tea, and Hernando obediently promised to swallow it.

Boneset tea was the old lady’s panacea for all ills; a sneeze, cough, or wet feet when noticed by her caused the good woman to instantly brew and force down the throat of the victim a bowl full of this nauseous draught, and Eletheer, who was her special charge, declared that she was forming the “boneset habit.” She could not help smiling as she handed the steaming bowl to Hernando saying, “Prepared strictly according to directions; one scant handful of the dried herb, being careful to omit blossoms (which nauseate), one-half pint of water and two tablespoons of molasses. Steep gradually one hour.” Hernando received it with a quiet “Thank you,” and swallowed it with seeming relish; then saying “Good-night,” entered his room and closed the door behind him.

Granny, whose room joined Eletheer’s, was awake when the latter tiptoed in, and the lamp was still burning. Hearing the door pushed softly to, she called, “Eletheer!”

“Yes, Granny, I’m coming,” she answered.

“Did you give Mr. Hernando the boneset tea piping hot?”

“Yes, Granny.”

“Did you put a hot brick in the bed?”

“No Ma’am, you didn’t tell me to, did you?”

The old lady looked severely at her and then said: “Go straight to the kitchen this minute and bring the one I told Margaret to put in the oven. If you intend to be a trained nurse, you must learn to think for yourself. That poor, motherless boy has taken cold. I wanted to soak his feet but he wouldn’t let me, and there is nothing like a good sweat to break up a cold. Tell him to be sure and tuck the covers in.”

“I will see that he has the brick and attend to him, Granny. You won’t remain awake any longer, will you?” she said, tucking the covers around the old lady, after which she started for the kitchen, putting out the light on her way.

The kitchen was vacant, but she found the brick and wrapping it in a little old shawl of Margaret’s hurried up to Hernando’s room. Her light tap received no response.

“I’m afraid he is asleep and hate to wake him,” she thought. “What makes Granny so set anyway! I’ve got to do it or displease her, so here goes,” and she gave a sounding knock.

“Come in,” said a faint voice and she opened the door.

“Who is it?” Hernando called, his teeth chattering.

“I. Granny told me to bring you this hot brick,” said Eletheer advancing.

“She is very kind. Thank you so much,” he managed to say.

Eletheer handed him the brick, and as he reached for it his hand came in contact with hers. It was like ice.

She glanced helplessly around. “If you are to be a trained nurse you must think for yourself,” rang in her ears.

“You are shivering with cold,” she said. “Didn’t the boneset tea do you any good?”

“I think it will.”

“Granny will feel dreadfully if I don’t do something,” she thought. “There, I have it, I’ll go for Reuben!”

“Reuben!” she whispered at his door, which was always ajar, “I think Mr. Hernando is sick. The boneset tea didn’t do him any good.”

“Very well, honey, jes’ yo’ go to bed, I’se comin’,” he answered cheerily.

In a few seconds he was beside Hernando, bringing as he invariably did, relief. Gradually Hernando’s shivering grew less, then finally ceased altogether and at last he fell asleep only to mutter in delirium which grew wild and wilder. Hour after hour passed yet that faithful black figure met every emergency as it came. Again and again were the heated pillows turned, was the wild call for “water! water!” answered, his every need anticipated, and time sped for both patient and nurse.

“Five o’clock,” thought Reuben, as he returned from replenishing the fire. His charge was asleep; so drawing an easy-chair beside the bed he settled himself for a nap. One by one each familiar object in the room fades from sight and he is in a foreign-looking city of narrow streets, dimly lighted by the soft glow of Chinese lanterns. The streets are thronged with Celestials weaving back and forth. Even Reuben is fascinated by the substratum of actual sin around him. It is a panopticon of strange sights; little rooms in which are huddled together groups of odd-looking women making shoes; eye and ear doctors busily operating on meek-faced patrons; unknown fruits and vegetables, costly wares and curious trinkets; omnipresent female chattels and moral and physical lepers jostle one another. One peep into an inner chamber, and with the sickening fumes of opium in his nostrils Reuben seeks the outer air. But hark! in this fantastic jumble surely he hears familiar voices. Following the sound through a seemingly endless maze of dark alleys, he suddenly stops in a small room gaudy with Oriental hangings. Even in the semi-darkness Reuben sees that there are three figures; one, that of a young woman, an Oriental, in an attitude of perfect abandon. She utters no word, but the smile from her eyes causes Reuben’s to fall in horror. The air clears a little and the two other figures are visible—Granny and Hernando! The latter’s head is bowed in shame. Reuben is shocked at the lines of dissipation in his face and to see how thickly sprinkled with gray is his hair—“Strange!” he thought, that he had not before noticed it.

Granny is pleading with him to forsake this den of depravity. Her hand is clasping his and those old, stern lines have melted into a smile of ineffable sweetness. The air is heavy and her voice not always audible, but Reuben hears:

“Blessed is the man that endureth temptation: for when he is tried, he shall receive the crown of life which the Lord hath promised to them that love him....

“But every man is tempted, when he is drawn away of his own lust, and enticed.

“Then when lust hath conceived, it bringeth forth sin: and sin, when it is finished, bringeth forth death.”

“You have had a bad dream, Reuben.”

The gray light of early morning peeped into the room, filling every nook and corner with the weirdness of unreality. Reuben looked vaguely at Hernando, lying quietly with an inscrutable smile on his face. He raised himself in his chair. Sure enough, there were the lines of dissipation and gray hairs! “’Deed, Massa, I has so!” he replied, as he went to replenish the fire.

“Surely, Reuben, you don’t believe in dreams!”

“I’se boun’ ter, Massa; didn’t Joseph’s and Pharaoh’s come true?”

“That is a disputed question. I don’t believe that people now-a-days dream dreams that have no connection with, or some proportion to their waking knowledge.”

“Mebbe so, Massa, but when Massa John was so dreffel sick down in Missouri, Massa Murphy’s dog howled t’ree times befo’ de do’. I sho’ly did b’lieve de Good Laud wanted Massa John Lauzee, how I did go trompin’ troo de grass aftah dat dog! Listen, Massa, aftah a-chasin’ dat dog laster time, I sat down by Massa John’s bed feelin’ po’ful sad, an’ I dreampt he was dead an’ I watchin’ in great tribilation of spirit. I done t’ink de Good Laud didn’t hearken to de moans an’ groans ob dis po’ niggah. Seemed like I’d go plum ’stracted. My ’tention was ’tracted by a bright an’ shinin’ light an’ outen it came a still, small voice: ‘Reuben, yo’ Massa will live, an’ yo’, not I, have saved his life.’ Massa Hernando, dem’s de berry words ob Doctor Hoff when de fever turned. Yes, Massa, I’se boun’ ter b’leeve dat when de Good Laud has a message fo’ us, He’ll mebbe give it in a dream.”

“Reuben!”

“Yes, Massa.”

“A drink, please.”

“Reuben!” there was a quaver in his voice now.

“Yes, Massa.”

“Reuben, my friend!” and—Hernando did not ask Reuben his dream. Hernando stirred uneasily, and presently raised himself on his elbow only to fall back with a groan. Instantly Reuben was beside him asking how he felt.

“First rate when I lie still, but the instant I attempt to get up my back seems broken.”

His face indicated that he was anything but well, and his voice sounded thick.

“Is yoah throat soah?” Reuben inquired.

“Not exactly sore. It feels as if it were not a part of my own anatomy.”

Reuben asked Hernando a few questions, examined his throat and quietly said he’d better go for a doctor. “But first let me bring yo’ a cup of coffee,” he added.

Margaret was in the kitchen, and with her assistance the coffee was soon ready and, after first making sure that everything was all right, Reuben closed and locked the door behind him and went to summon the doctor.

Before long the doctor came; good, genial Doctor Brinton whom every one loved.

“Hello, Young Nevada!” was his breezy greeting. “What new disease have you introduced into our valley? Reuben, my good fellow, hand me my bag.”

It was brought.

“You feel as if you’d been licked, my boy,” he said gaily as he felt the swollen glands in Hernando’s throat. “Been among the miners lately?”

“No. Uncle warned me that many were sick with diphtheria.”

“All the same, you have a suspicious-looking throat, my boy,” replied the doctor gravely.

“Do you think it diphtheria?” Hernando inquired anxiously.

Dr. Brinton looked puzzled. Plainly this was not diphtheria, as during the night his temperature must undoubtedly have been high.

“A nasty throat, but what the deuce is the matter with the boy anyway!” he inwardly commented, then turning to Hernando said, “Your throat looks uncommonly like it, but your symptoms are not all such. Never mind though, Reuben here is worth ten doctors, so you are all right.”

“But the whole family would be infected.”

“Not by a jug-full! A germ cannot live long under Reuben’s ruthless destruction.”

Bidding the latter follow him to the sleigh for some disinfectants, Dr. Brinton went out, and when beyond hearing, said: “Reuben, my man, all your skill will be needed if we pull that fellow through. The action of his heart is decidedly bad. Stimulants, nutritious food and good nursing will do more than I can. Frankly, I never before saw a case exactly like this and am not at all sure it is diphtheria.” He then went in search of Mr. De Vere.

The latter was shocked, and of course everything in the house was placed at Dr. Brinton’s disposal.

“Well,” said the doctor, “an ounce of prevention—you know. This may be diphtheria, and it may not. In any case it’s best to be on the safe side. I don’t go much on religion, as you know, so am frank to say that I think the Lord made a mistake when he put a black body on that white soul. When ‘Gabriel sounds his trump’ for me I should feel safe with Reuben to pilot the way.”

Mr. De Vere’s eyes grew dim.

“And,” the doctor added, “his word is law in this case. No one but he goes into that room; nothing comes out but through him.” And Doctor Brinton drove off singing

“There is a happy land—”

It proved indeed a serious case. Hernando’s heart, never very strong, under the action of this insidious poison and a restless spirit came very near failing altogether. But once more the eternal vigilance and conscientious care of Reuben assisted Nature and she conquered, and the work of repair progressed steadily. Dainty trays tempted the feeble appetite. Reuben prepared them himself and each one was a surprise. Somehow he knew just what he liked, to Hernando’s surprise.

All the family vied with one another in making him comfortable. Mr. De Vere kept him posted in regard to the mine, the articles of incorporation, and said that operations were to begin in March. He did not tell him that they were waiting for him to be ready, but Hernando guessed it and exerted himself to regain strength as much as he was allowed.

One day Mr. De Vere announced that the mythical Valley Railroad was to materialize. The company had been chartered the week previous in New York City with Mr. Valentine Mills as treasurer. A contract had been made with the banking house of Cobb, Hoover and Company of the last-named city to sell the railroad stock, and the bonds were going like hot cakes, so the company felt itself warranted in beginning work at once.

Mr. De Vere also told him that Elisha Vedder, a young civil engineer of St. Louis, through his recommendation, was to arrive the following week and survey the route, which seemed a feasible one, and better in respect to grades than the company anticipated. The need of the gold mine had been heralded abroad, and outsiders also were clamoring for railway facilities.

Genung was jubilant, and his daily visits to Hernando, now out of quarantine, only increased that young man’s impatience to be actively engaged with the others in this great enterprise.

Granny had long since taken him under her wing. His deference to her opinions, and old-fashioned chivalry to all women, completely won her. There existed a strong attachment between them. She would sit by the hour in his room recounting adventures of pioneer days and her vivid pictures interested him intensely. She possessed an inexhaustible fund of them; her memory never deceived, and she regarded the slightest deviation from the exact truth as criminal.

“Where is Miss Eletheer?” Hernando inquired of her after she had just finished a most interesting story. “I have not seen her since dinner.”

“Call the child by her plain name. She has gone daft over that mine and very likely is there. Celeste!” she called, “come and sing for Hernando. He is lonesome.”

Hernando protested, but the sight of Celeste’s sweet face quieted all remonstrance. She flitted in gaily with her guitar, and Hernando would have been an exception to most of his sex had he not bowed in adoration before this beautiful creature.

Music had no charm for Granny so she left them to enjoy it by themselves.

One tiny slippered foot peeped from under Celeste’s skirts and rested upon the guitar case, while her slender white fingers wandered