CHAPTER VIII

THE last week in April had arrived and in a few days came Celeste’s wedding. Hernando was returning from town after a call at his uncle’s where his cousin Mary Genung was convalescing from typhoid fever. Eletheer De Vere had been with her and bravely nursed her through. Everything seemed strangely quiet, only the sound of the crushers breaking the stillness, and he strolled along so deeply absorbed in thought that he did not hear a light footstep behind him, and almost started when his arm was clasped by slim white fingers and a merry voice said playfully: “There, you naughty boy, I’m completely out of breath trying to catch up with you.”

It was Celeste, and she raised her glowing face to his with an expression of mock severity.

“I certainly did not hear you, Celeste,” he replied honestly.

Her hands were full of trailing arbutus which filled the air with its delicious fragrance.

“Then I will forgive you,” she said, pinning a cluster of deep pink blossoms on his coat.

“What are these beautiful flowers?” he said, smelling of them.

“For shame!” she exclaimed, “not to be acquainted with trailing arbutus. The woods are full of it. Whittier calls it the Mayflower, and says, ‘It was the first flower to greet the Pilgrims after their fearful winter,’” and with a happy smile she repeated:

“‘Yet God be praised,’ the Pilgrim said,

Who saw the blossoms peer

Above the brown leaves, dry and dead,

‘Behold our Mayflower here.’

“O sacred flowers of faith and hope,

As sweetly now as then,

Ye bloom on many a birchen slope,

In many a pine-dark glen.”

“I think I have heard Mary speak of them,” said Hernando, “but I never saw them before.”

“How is Mary getting on?”

“She was down stairs to-day for the first time.”

“Eletheer really intends to be a nurse,” Celeste said, “but it must make one become morbid to see so much suffering.”

“It will never have that effect upon Eletheer,” Hernando said gravely.

“Eletheer is eccentric. She always selected her associates from among such queer people. Mary Genung is the only nice girl she cares anything about.” Here Celeste laughed and continued calmly, “Let me name a few of her friends: Father Perry, Uncle Mike, the Dugans, every one of the miners, Pat McGinn, Doctor Brinton and Mary Genung.”

Hernando could not resist laughing. “Am I not among them?” he said, sobering instantly.

“You,” and her laugh was infectious. “She seems to have adopted you. Some one made a remark about you which she interpreted as disparaging, and he must have felt uneasy under her sarcasm.”

“She is very loyal to those she cares for.”

“And those whom she dislikes know it.”

Elisha had seen them coming from the piazza and met them at the gate. How tenderly he drew Celeste’s arm within his own and what a world of devotion was pictured in his honest face. Hernando watched them go. Once Celeste looked back. He was smelling the arbutus she had given him.

Supper had been cleared when they arrived, but Margaret never forgot the “chillen” and Celeste, followed by Elisha and Hernando, went immediately to the kitchen.

Jack’s health was really in such a condition as to excite apprehension, and an inherited weakness of the lungs predisposed him to pulmonary troubles. He had been preparing to enter college, but close application to study had completely broken him down, and he was obliged to give up the aim of his life, but took the disappointment philosophically and when the doctor suggested roughing it on the plains of Texas, arrangements were immediately made to follow his advice. It was now Tuesday, and Thursday was the day appointed for Celeste’s marriage. Jack intended going with them on their wedding journey as far as Vicksburg, then continuing on alone to Texas. All his preparations were completed and he anticipated the trip with much pleasure. Elisha seemed like a brother already—indeed all the family received the announcement of his wish to make Celeste his wife as a foregone conclusion. The wedding was to be a simple one, no one outside of the family being invited, and immediately afterward they were to leave for the South.

Jack’s nature was buoyant. Like Celeste, he viewed life from its sunny side. Admired, sought after, it is not to be wondered at that his nobler traits lay dormant. Mrs. De Vere idolized her only boy and in her estimation he possessed not one fault. Hers were the eyes that detected the change in Jack, and in his capacious trunk was packed every comfort for her boy. No one knew of the tears she shed in secret and Jack only suspected it. He found Eletheer folding heaps of fleecy garments designed for Celeste’s adornment. They were mysteries to him and seeing she was in a hurry, he put on his hat and went out.

The last article stowed away, Eletheer closed the trunk and went down into the dining-room, and being tired and wishing to be alone, she closed the door and threw herself into a large easy-chair before the fire. The night air was chill yet and the fire shed a grateful warmth. She had been seated some minutes before she became aware that she was not the only occupant in the room, and turning her eyes toward the deep eastern window, she saw Hernando seated among the cushions.

“Pardon me,” she exclaimed with a start, “perhaps I intrude.”

“From the manner in which the door closed, you will be the one intruded upon if I remain.”

“Don’t talk nonsense, Hernando. Your presence is never unwelcome. I am actually blue and do not wish to infect others.”

“You would tell me that my stomach is out of order.”

“Which is undoubtedly true of mine. But in all seriousness, Hernando, that attack of diphtheria you had last winter has left bad effects. Your entire countenance is somehow changed and your voice has never been the same since. For the last three days you have seemed half asleep. Reuben is really becoming concerned about your condition.”

“Reuben is a noble fellow but somewhat of an alarmist, I fear,” replied Hernando.

“I understand the meaning of the word ‘alarmist’ to be ‘one who needlessly excites alarm’, which certainly does not apply to Reuben, and when he says ‘somethin’ is goin’ to happen,’ it invariably does happen.”

“What is his latest prediction?” Hernando asked with a light laugh.

Eletheer could not help smiling in return as she replied: “Nothing in words, but his actions indicate that some calamity is impending over this family.”

“What was it you quoted to me the other day, ‘Nothing can happen to any man that is not a human accident, nor to an ox which is not according to the nature of an ox, nor to a vine which is not according to the nature of a vine, nor to a stone which is not proper to a stone.’ If then, there happen to each thing both what is usual and natural, why shouldst thou complain, for the common nature brings nothing which may not be borne by thee.”

Eletheer looked very sober and he continued, “Far be it from me to disparage Reuben, but like all of the colored race he is superstitious. You must not remain so much indoors. Mary’s illness and the preparation for this wedding have made you morbid,” he said, shivering slightly.

“Are you cold?” she asked in some surprise, at the same time poking the fire vigorously. The blaze which followed illuminated the room, revealing Hernando in a vain effort to repress a chill.

“I fear you are ill, Hernando.”

Reuben here entered with an armful of wood. His observing eye recognized at a glance the indications of suffering which Hernando could not conceal, and hastily depositing his burden, he returned in a few minutes with a glass which he handed to Hernando saying, “Heah, my boy, drink dis hot toddy. Yo’ bettah keep out of dat mine. Dampness haint good fo’ rheumatism.”

Hernando drank the mixture and with Reuben’s assistance went up to his room. Striking a light, the faithful negro opened the bed and turned to aid his charge in disrobing. The latter’s face was positively livid.

“I reckon I gave yo’ a po’ful dose, Massa. Yo’ head is ready to pop,” said Reuben apologetically.

“I do not understand it, Reuben. Of late, stimulants, even in infinitesimal doses, always affect me in this way.”

“I’d bettah put yo’ feet in good hot watah, it will draw de blood from yo’ head.”

Hernando barely retained an upright position during this operation. He felt literally “dead for sleep.” Reuben kept his own opinion to himself, mentally determining that the next hot toddy should be less hastily measured, and he hurried his patient into bed. In less than five minutes Hernando snored loudly, and Reuben thought best to leave him alone; so, after tidying the room, he softly closed the door, chiding himself severely for his supposed carelessness, and returned to finish the chores.

Eletheer still waited in the dining-room and after being told that Hernando would probably be all right in the morning, she retired. Not so with the faithful Reuben. After attending to the thousand and one little tasks which he conscientiously and systematically performed, his pallet was spread by Hernando’s door that he might be ready in case of need. Several times during the night he stealthily crept to Hernando’s bedside only to find him in that same heavy sleep.

“Dat sleep means somefin,” he soliloquized uneasily; and earlier than usual the kitchen fire was kindled and his part of the daily routine begun.

Hernando had not stirred, but he breathed more easily and was bathed in perspiration. His left arm hung over the edge of the bed and as Reuben with tender solicitude raised it and was about to replace it under the cover, the sleeve fell back revealing several small, dry, red spots which, unlike the adjacent skin, were perfectly dry. Reuben stared. This struck him as unusual. Here the sleeper moved his head slightly to the left and just below the right ear were some more of these spots. These also were perfectly dry. He recollected having heard Hernando mention being troubled with “blood-boils.”

“I reckon de hot toddy stirred his blood up, po’ boy. He needs a good clarin’ out,” Reuben mentally said, but he felt uneasy and as soon as Mr. De Vere was heard stirring, the former knocked at his door expressing a wish that Dr. Brinton be summoned.

“By all means,” Mr. De Vere said. “Do you think his case serious? What kind of a night did your charge pass?”

“He done slep’ all night, Massa John, and is sleepin’ hard now. The po’ful strong toddy might do that, but I ’clare, Massa, I jes’ feel he’s dreffel sick.”

“What do you think is the matter?”

“I jes’ dun know.”

“Then we will have a physician settle the question,” replied Mr. De Vere, stepping to the telephone.

“Dr. Brinton is not well,” the answer came. “Is the call imperative?”

One glance at Reuben’s face and Mr. De Vere answered, “I am sorry to learn that the doctor is sick, but fear we must have medical advice at once. Will he kindly send some one?”

After a long pause, Dr. Brinton himself answered. Hernando’s symptoms under Reuben’s dictation were given, and through the ’phone, Dr. Brinton’s laugh followed by a fit of coughing could be distinctly heard. Then he said his assistant would be up immediately after breakfast.

“Now Reuben, my good man, don’t worry any more about it. You know he has malaria—at least he occasionally suffers from febrile attacks—and now undoubtedly has taken cold. Your hot toddy will fix him, and if it does not, the doctor will do all necessary,” and he dismissed the subject.

Massa John’s will was law for Reuben, and though he could not rid his mind of a feeling of indefinable dread, after another peep into Hernando’s room he went to assist Margaret in the kitchen.

Nine o’clock brought, not Dr. Brinton’s assistant, but Dr. Herschel, a celebrated dermatologist who was stopping in town for the purpose of investigating the climatic conditions at Shushan and the medicinal properties of mineral springs there. He alighted deliberately and turned to survey the prospect. Little rivulets of melting snow danced musically down the mountain side, the fresh woody smell from dried leaves was wafted to his nostrils, unconsciously his head was thrown back to better fill the lungs with this exhilarating air, and he bared his head as if in deference to the Giver of such blessings.

Eletheer was watching from an upper window and her heart fluttered as she thought of meeting this great man face to face. “Just like good Dr. Brinton,” she said to herself. “None but the best for our family—but Hernando is worthy of it. I do wonder what is the matter with him anyway. Reuben seems so worried. Dr. Herschel takes his time. Probably as his name is made, he does not need to inconvenience himself for the sake of others.”

He raised his eyes to the window before which she sat and seeing her, bowed slightly and advanced slowly toward the house.

“So this is the great scientist,” she said aloud, disappointment pictured in every lineament of her face—and indeed any casual observer would never give him a second thought. Reuben, always a well-bred servant, could barely restrain his impatience, and without waiting for the doctor to ring, he opened the door and unceremoniously ushered him into the library where Mr. De Vere was absorbed in the morning papers.

“De doctah, Massa,” Reuben announced, immediately ascending to Hernando’s room.

“Ah, good morning, Doctor,” said Mr. De Vere extending his hand. “Glorious weather this. Pray be seated.” He drew a great easy-chair before the western window which overlooked the city and pointing to the blue hills among which lay Shushan, remarked: “Like Hernando, you too are striving for the betterment of suffering humanity, only on different lines.”

Dr. Herschel’s glance followed his. His eyes were deep set, but their color was lost in the brilliancy of the mind which saw through them more than this world of material facts and threw the light of its genius into unexplored regions. Without removing his glance, he said in a low, even-toned voice, “I believe you surveyed out that tract of land.”

“Yes, and found it an unsavory job,” Mr. De Vere laughed.

Dr. Herschel’s countenance wore no answering smile as he replied: “True, the stench is almost overpowering, but the waters from ‘Stinking Spring,’ particularly, I believe to possess undoubted curative properties.”

“I sincerely trust they may, but to me that spot is the most obnoxious on the globe and the poor unfortunate who laved in that water would be a martyr indeed.”

“All of us are more or less,” replied the doctor abruptly, “but time is passing, shall I see the patient now?”

Reuben’s quick ear caught the question and almost instantly his black form appeared in the doorway, and without more ceremony Dr. Herschel was escorted to Hernando’s room. On the way upstairs he touched Reuben on the shoulder with, “Have you excluded all but yourself?”

“Yes, sah.”

“Why?”

By this time, they had entered the room and closed the door.

“Kase, Massa, it mout be ketchin’.”

“Have you ever before seen a case like this?”

“Not exac’ly, sah.”

“How long has he slept like this?”

Reuben gave a very correct account of Hernando’s condition since the evening previous—not even omitting the toddy, nor to deplore his own supposed carelessness. Not a single symptom was forgotten.

The physical examination over, during which Hernando remained limp, the doctor again turned to Reuben, “Has he ever spent any time out of the United States?”

Reuben did not know, but felt sure that Mr. De Vere would.

“That is all then, my good fellow. Let your patient sleep. This is an infectious disease, so be very careful to cleanse your hands with this”—handing him a prescription. “Use every precaution which an intelligent nurse should.” He then sought Mr. De Vere who anxiously awaited his verdict.

“Well?” the latter questioned.

Following him into the library, Dr. Herschel expressed a wish that Mr. Andrew Genung be sent for.

“We telephoned him early this morning and I am surprised that he is not here now,” said Mr. De Vere.

Even as he spoke, that gentleman’s portly figure appeared at the door and after a short greeting, he dropped into a chair, panting for breath, but managed to gasp, “Well, Doctor, we are fortunate in obtaining your service. Is our boy’s condition precarious?”

“First get your breath,” replied the doctor, “and then my diagnosis will be materially strengthened if you are able to correctly answer a few questions.”

Like all who came within this magnetic man’s influence, the two men before him, in dread expectancy, instinctively felt themselves in the presence of one who has conquered his most dangerous enemy, himself, and as a logical sequence, his trained intelligence would be rightly directed. Neither of them, though, appreciated the gentle tact by which their minds were being prepared for the shock awaiting them. After a short pause, Dr. Herschel asked—“Has your nephew ever passed any time out of the United States?”

“No,” replied Mr. Genung in some surprise.

“Has he ever married?”

“No.”

“He was born and reared in Nevada, I believe. Where educated?”

“San Francisco.”

“And probably, like too many young men of that age, Chinatown had its attractions.”

Mr. Genung’s face became purple with indignation, but his questioner did not flinch, only a look of divine pity came into his face as the question was repeated.

“Pardon me, Dr. Herschel,” Mr. Genung replied, rising and preparing to leave, “I fail to see the application of that question to my dear nephew’s present condition.”

“Very well,” came the deliberate reply, “you are not legally obliged to answer, neither is your nephew; but as the latter’s medical adviser and would-be friend, I have a moral right to be enlightened on everything pertaining to his good. True, the question asked, though a leading one, is not necessary, for his symptoms are sufficient to expel all doubt; but when a physician diagnoses a case as one heretofore unknown in these parts, he naturally likes to substantiate his opinion by all available evidence.”

With Mr. Genung, family matters were as strictly kept as the Ten Commandments, but the doctor’s last remark disturbed him more than he cared to admit. Twirling his hat nervously, he said—“Supposing it had. What if, for one brief year, his habits had not been such as a parent commends—a young man must ‘sow his wild oats’—how could the knowledge of that fact affect your diagnosis?”

“Make it absolutely certain. I have traced similar cases to Chinatown. It is a far too productive soil for the sowing of wild oats. One sometimes reaps where he has not sown. The disease is leprosy; but, contrary to the universally accepted belief, a cure has been found.”

Dead silence, broken only by a sound of labored breathing, followed this announcement.

“Yes,” he continued, “‘Old Ninety-Nine’s’ cave contained a rarer treasure than money and jewels in the form of a proven cure for this justly dreaded malady.”

There is no sight more pathetic than a proud man humbled. Mr. Genung, with all his boastful pride of race and family, told that one in whose veins his own blood flowed was an outcast, unclean from this loathsome disease, a leper, while close upon this, conscience whispered, “What of the poor victim?” felt a compassion for his wayward brother’s only child suffuse his whole being. Tears coursed down his rugged cheeks and utterly broken in spirit, he looked appealingly at Dr. Herschel while his whole frame shook as with ague.

Mr. De Vere sprang to his assistance and Dr. Herschel administered a restorative, bidding him lie down for a few minutes, and his order was obeyed with child-like confidence.

“Now,” resumed the doctor, when the excitement had somewhat subsided, “my plan is this: to at once remove our young friend to Shushan—accommodations there are meager, but this is easily and quickly remedied, and I, myself, will remain with him until he is fully under the application of my treatment.”

“All alone in that detestable wilderness!” Mr. De Vere exclaimed.

“No, my dear sir, very soon he will be joined by another man (also a patient), and they can mutually assist each other.”

“God be merciful!” Mr. Genung moaned.

“Their home,” the doctor continued, “shall be light, airy and attractive, the library complete. I assure you that nothing necessary for their comfort will be omitted. Barren and forbidding as that spot seems, it contains much that is interesting, and best of all, that for which the brightest minds of all ages have sought—A CURE FOR LEPROSY!”

“How long do you think this stupor will last, Doctor?” asked Mr. De Vere.

“I cannot say, but asleep or awake, we must make arrangements for his removal this night. You understand that his isolation is to be complete?”

“Not even communication by telephone?”

“Even that. Were it known that Hernando has leprosy, complications might arise. Fearful as the disease is, it is not contagious, but it would be a difficult matter to convince the laity that contagion and infection are not synonymous. Am I to depend on your co-operation?”

“Oh, yes,” came the answer in unison.

“Reuben will collect together his effects”—with an accent on the name, which both understood—“and prepare him for the trip at about ten o’clock to-night; I, with a trusty man, will be here with a conveyance for Shushan.”

A heavy sigh from Mr. Genung.

“And now,” said the doctor cheerfully, “devotion is commendable only when rightly demonstrated. Let me know if he awakes. Good-morning,” and he was off.

Even his enemies would have pitied Andrew Genung as he sat there staring vacantly at first one and then another. Hernando’s coming and subsequent aid in discovering “Old Ninety-Nine’s” mine he had viewed in the light of a manifestation of God’s pleasure to smile on this valley, and that He had chosen one of the good old name “Genung” to be the means, had made his heart swell with pious pride. Now he could only pray; “Heavenly Father, have mercy on my poor boy. Forgive him, for he knew not what he did!”

Mr. De Vere went upstairs to deliver Dr. Herschel’s verdict to Reuben. His hand was on the knob of Hernando’s door; but, like a spirit, Reuben appeared on the threshold and gently but firmly motioned him back with,—“Yo’ can’t come in hyah, Massa, Massa John!”

“Reuben!” Mr. De Vere’s tone was one of dignity.

“Dr. Herschel assures us that this disease is not contagious, nor as broadly infectious as has been believed.”

“Drefful sorry to displease yo’, Massa; but odahs am odahs.”

Mr. De Vere stepped back abashed, not at the gentle rebuke implied in those words, but before this perfect example of the dignity of service, unswerving fidelity to conviction, unselfish devotion to those held dear.

“Far be it from me to tempt you, Reuben,” Mr. De Vere said humbly. “You understand that Hernando has leprosy, and that, awake or asleep, you are to have him ready to be moved to Shushan by ten o’clock to-night.”

Not a muscle in that black face moved; and fearing he had not understood, Mr. De Vere repeated—“Leprosy.”

“Yes, Massa, I s’pected it when the doctah was hyah.”

A slight noise in Hernando’s room attracted Reuben’s attention and he quickly entered it, locking the door behind him.

Eletheer came out of the library where Mr. De Vere had been closeted with his family for nearly an hour. No outsider will ever know how the awful truth was told there, but the girl Eletheer came out of that room a woman. She wandered aimlessly downstairs. Not a cloud dimmed the intense blue of the heavens, and all nature seemed quivering with new life. The sunny valley lifted a smiling face but Eletheer saw only—Shushan.

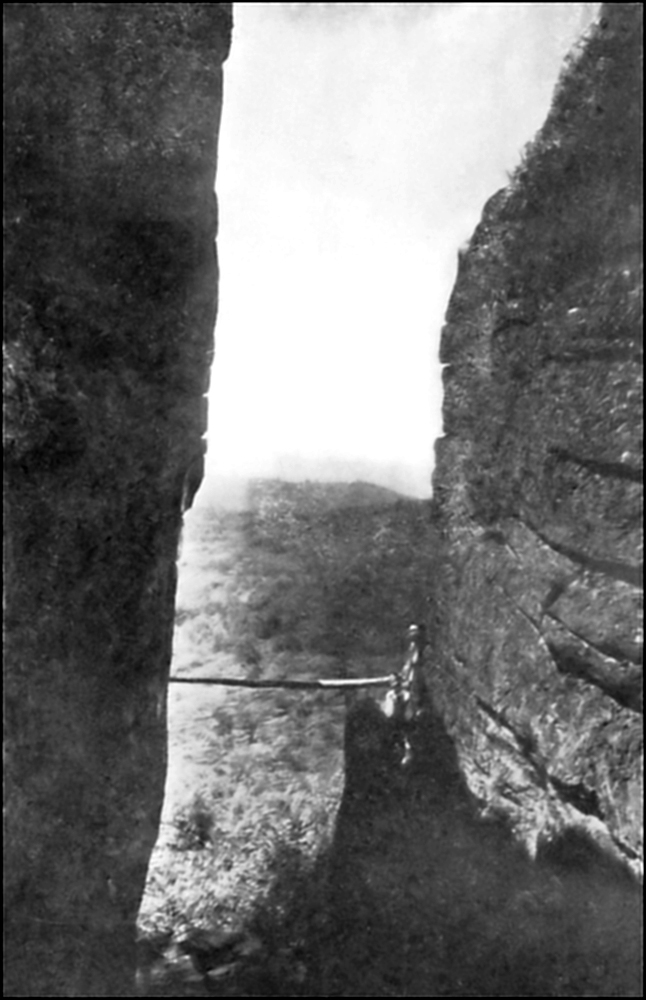

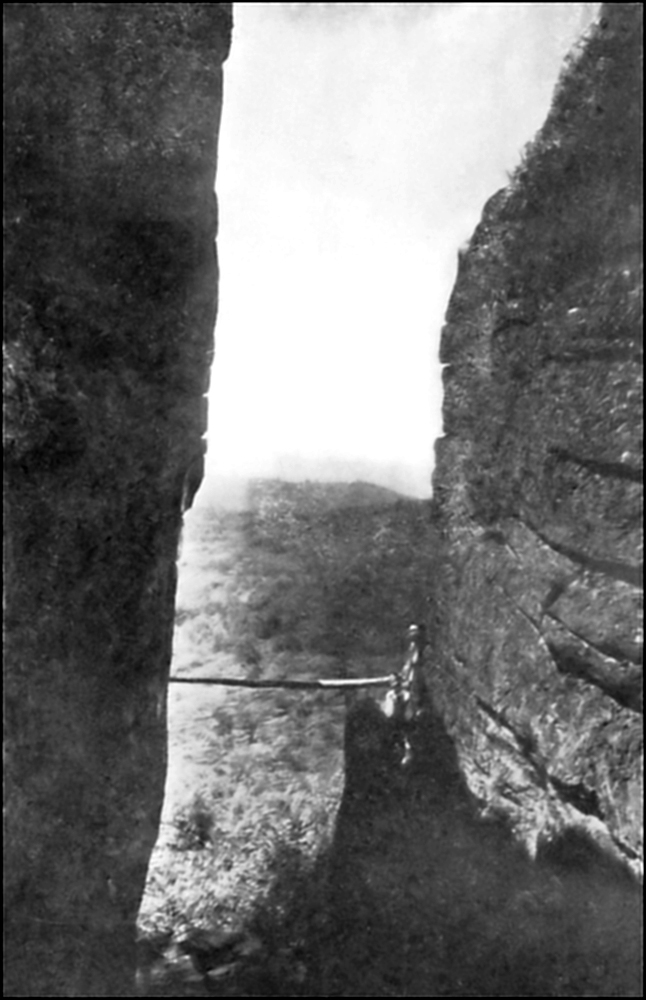

Into this den of venomous serpents only the hardy dared penetrate

This extensive tract of land extended from the Rochester line to the “Low Right.” Portions of it were capable of being converted into average, tillable land but the greater part was rough, hilly and barren. This latter condition especially applied to the eastern portion, which opposed the Shawangunk Mountains: bare, rocky walls rising in successive steps, brokenly dizzy cliffs over which the northeasters swept unobstructed, fit abode for the shades of departed warriors as they had been the scene of many an Indian ambush. True, there were some shady haunts of gigantic pine, hemlock and chestnut, but into this den of venomous serpents only the hardy dared penetrate, and these never more than once.

In the heart of this amphitheater boiled a spring so offensive as to have earned the name “Stinking Spring.” The rocks from which it issued were blackened, denuded of all vegetation, and every living plant within reach of the fumes withered and died, but here was a paradise for reptiles which attained prodigious size and thronged in numbers incredible.

Old settlers claimed that some sort of connection existed between Shushan and “Old Ninety-Nine’s” cave, as, when the mysterious “light” appeared on the mountains, an answering flash rose above Shushan, but no one attempted an explanation.

Locally, this spot was regarded with dread, wiseacres declaring it haunted, and Dr. Herschel’s purchase of the same excited much adverse criticism, but he was left in undisputed possession.

Here, for years to come, was Hernando to dwell; and, disfigured beyond recognition by the “Curse of a God of purity,” he would find his “Waterloo.” The utter futility of human resistance to natural laws had received another scientific verification; but oh, how disproportioned was the punishment to the offense!

Completely wrapped in thought, Eletheer did not see Dr. Herschel who just then appeared around a bend in the path, and she started hysterically at his greeting.

He had been up at the mine and was making a short cut through the barnyard to the road where, unnoticed by Eletheer, his horse was still tied. His practiced eye detected at a glance the traces of tears which she defiantly repressed and, pointing to a rustic bench, he said,—“Come, let us sit in the sunlight and see if you are in earnest about becoming a trained nurse, which Dr. Brinton tells me you have decided to do.”

“Yes,” she replied simply, “my grandmother thought I had a real talent for nursing.”

Dr. Herschel looked at her fixedly. This was not the first girl whom he had seen possessed of a “real talent” for nursing, whose heart “yearned for the sweet joys of ministering to the afflicted”; but in his experience the majority of these ardent maidens had been quickly disillusioned. Possibly the girl beside him was different. True, she knew nothing of the world and all its distractions, but she did not seem sentimentally inclined. Her behavior during the recent unhappy occasion was eminently praiseworthy in one of her temperament and years.

“Then too,” she added, “Reuben says I’ll make a good nurse and he is a natural nurse.”

“H’m!” Dr. Herschel had seen “natural nurses” before; but at the mention of that black man’s name his expression visibly softened; no fair-minded critic could question his ability.

“How old are you?” he asked.

“Seventeen.”

“Plenty of time in which to consider so serious a question. First get a good education, and then if you still wish to enter upon that life I will assist you in doing so. From time immemorial nursing has been the field of usefulness peculiarly adapted to women. History’s pages are dotted with the names of heroines in camp, field and plague-stricken districts, in short, wherever the sick and wounded have needed care nurses have lived a life of such unselfish devotion as to have earned the gratitude of millions. We bow our head in reverence to their memory; but we are approaching a practical age in which science and mechanics will be the ruling forces. The time is not far distant when nursing will be a recognized profession, in line with the other educational branches, and expert training an unquestioned necessity. The trained nurse of the future must be an open-eyed, earnest woman with a working hypothesis of a life. She will be keenly alive to the fact that people of culture and refinement into whose homes she may be sent, require an approach, at least, to the same qualities in the one who ministers to their needs. Relations between nurse and patient are peculiarly close and sacred”;—involuntarily Dr. Herschel looked upward toward Hernando’s window—“she will be the recipient of confidences, often enforced, which no true nurse can violate. In short, her influence in any household is almost unlimited for good—or bad. Any nurse who chooses this life with either no conception of the magnitude of the work or from some ulterior motive, must ultimately suffer defeat. You see, Miss Eletheer,” he continued, “that is largely a question of business, with a business woman’s responsibilities. A nurse must be just, loyal and self-sacrificing from an impersonal standpoint, believe in herself, and have perfect control over her emotions. She must ‘take things as they are.’”

Dr. Herschel was a peculiarly gifted man aside from his professional attainments. A natural critic of human nature, wide experience had de