Chapter 7:

Things You Might Not Have Known About The Northmen

The Anglo-Saxon Myth

In Appendix F to THE LORD OF THE RINGS Tolkien writes:

Having gone so far in my attempt to modernize and make familiar the language and names of

Hobbits, I found myself involved in a further process. The Mannish languages that were related to the Westron should, it seemed to me, be turned into forms related to English. The language of

Rohan I have accordingly made to resemble ancient English, since it was related both (more

distantly) to the Common Speech, and (very closely) to the former tongue of the northern

Hobbits, and was in comparison with the Westron archaic.

...a few personal names have also been modernized, as Shadowfax and Wormtongue[1].

[1]This linguistic procedure does not imply that the Rohirrim closely resembled the ancient

English otherwise, in culture or art, in weapons or modes of warfare, except in a general way due to their circumstances: a simpler and more primitive people living in contact with a higher and more venerable culture, and occupying lands that had once been part of its domain.

Despite this admonition from the author himself, many people choose to believe that the

Rohirrim were indeed modeled closely upon the Anglo-Saxons. I am unlikely to persuade the

hardened heart that this view might be erroneous, but I present below some observations about

the Anglo-Saxons and the Rohirrim.

Why did Tolkien use Old English to represent the language of

Rohan?

Perhaps the most commonly cited argument for ignoring the author's warning against identifying

the Rohirrim with the Anglo-Saxons is the fact that he used Old English to represent their

language.

Christopher Tolkien published some of his father's loose notes concerning the geography and

background of Middle-earth in THE TREASON OF ISENGARD. Of languages, J.R.R. Tolkien

wrote:

Language of Shire = modern English

Language of Dale = Norse (used by Dwarves of that region)

Language of Rohan = Old English

'Modern English' is lingua franca spoken by all people, (except a few secluded folk, like Lorien) -

but little and ill by Orcs

-59-

Parma Endorion

In UNFINISHED TALES Christopher Tolkien writes:

"It is an interesting fact, not referred to I believe in any of my father's writings, that the names of the early kings and princes of the Northmen and the Ëothëod are Gothic in form, not Old English (Anglo-Saxon) as in the case of Leod, Eorl, and the later Rohirrim.

Vidugavia is Latinized in spelling, representing Gothic Widugauja ('wood-dweller'), a recorded

Gothic name, and similarly Vidumavi Gothic Widumawi ('wood-maiden').

....Since, as is explained in Appendix F(II), the language of the Rohirrim was 'made to resemble ancient English', the names of the ancestors of the Rohirrim are cast into the forms of the earliest recorded Germanic language.

"Old English" actually consisted of various dialects of an older language that was spoken by many tribes in northern Europe. Partly because of their isolation in the British Isles, and partly because of a unique mixture of influences, the dialects of the Anglo-Saxons diverged from the

"main tree", so to speak. This divergence was gradual from the 5th Century up until the 11th Century, when the Norman Conquest introduced French into the upper echelons of English

society.

Concurrent with the divergence of Old English was the development of Old Norse, which began

with a "phonetic shift" that occurred over a period of about two centuries, typically given as the Seventh and Eighth Centuries, so that by the time the Vikings (Danes) started settling in England in the Ninth Century, their language was changed enough to be "different" from Old English (and other German dialects on the Continent).

Tolkien used this concurrency of Old English and Old Norse to imply a concurrency between

Rohirric and Dalish, with both deriving from the more ancient language which he chose to

represent with Gothic:

Old Northman Gothic

| |

+------+--------+ +--------+--------+

| | | |

Rohirric Dalish Old English Old Norse

This linguistic device works well for native English speakers because Old English still sounds

enough like modern English in some respects that we can feel more comfortable with the

language of Rohan than we do with the names of the Dwarves (and the Kings of Dale: Girion,

Bard, Bain, Brand). The Dalish sounds "foreign", whereas the Rohirric sounds "archaic", and this effect underscores the distance between the Rohirrim and the Men of Dale.

In fact, because the hobbits of the Shire still had a few words in common with Rohan, the

language of Dale needed to be more "distant" from their perspective. Thus modern English and Old English were excellent choices for representing the various relationships between all the

languages.

-60-

Essays On Middle-earth

Hence, Tolkien's use of Old English to represent the language of the Rohirrim does not in any

way favor the refutation of his admonition not to identify the Rohirrim with any particular tribe or nation.

But what about "Beowulf?"

Didn't Tolkien use material from the classic Anglo-Saxon poem?

“Beowulf" had an unmistakable influence on Tolkien's work, and other Anglo-Saxon literature also influenced him. He was, after all, a philologist specializing in the study of Anglo-Saxon, though he was also quite knowledgeable in other languages.

But though "Beowulf" survived in an Anglo-Saxon manuscript, it is a common mistake for people to think that it somehow represents an Anglo-Saxon culture or world-view. The poem is

thought to have been composed sometime in the 8th Century (700s) when the Angles and Saxons

still had close ties with Continental Germans. It was very common for the skalds to travel from land-to-land, telling the same stories and poems to audiences in many regions of the north.

The story of "Beowulf" unfolds in Scandinavia and it concerns the Danes and Geats (a people of southern Sweden). There are in fact some historical names intermixed with the fictional

characters. Many people have commented on the resemblance of Theoden's hall in Edoras to

Heorot, the great hall of Hrothgar in "Beowulf". But Heorot was merely a typical northern hall.

Such structures were built by the Scandinavians and Germans, and not just the Anglo-Saxons.

There is nothing peculiar to the Anglo-Saxons in either Heorot or Theoden's hall.

Another popular element people point to is the similarity of Eowyn's cup-giving to the "Anglo-Saxon Cup Ceremony". But the Cup-giving was a custom among all the German and

Scandinavian tribes, and even among many Celtic peoples. Highly ornamental drinking cups,

horns, and cauldrons have been found throughout Europe. In fact, the Cup-giving was so well-

known that one gruesome legend tells us that the King of the Lombards forced the daughter of

the last King of the Gepids to marry him after the Lombards conquered the Gepids. He forced the princess to drink from a gilded cup made from her father's skull.

"Beowulf" was undoubtedly a classic tale that was heard in many ancient halls throughout the northern world. It would have been recognized in many lands and so represents a "northern

European" culture, rather than an Anglo-Saxon one. Therefore any elements that Tolkien

borrowed from Beowulf and other "Anglo-Saxon" poems like "Widsith" and "Deor" were pretty generic in cultural terms.

-61-

Parma Endorion

Okay, but were The Rohirrim unlike the Anglo-Saxons in any

Significant way?

Absolutely.

Tolkien went to great pains to detail the culture of Rohan. It would be impossible, had he

intended to make them look like Anglo-Saxons, for us to find significant differences between the Rohirrim and the Anglo-Saxon people. But there are significant differences.

For one thing, the Saxons were a seafaring people. The Rohirrim never used ships of any sort.

They undoubtedly had some knowledge of boats, but Tolkien's Northmen are not pirates in any

phase of their history, whereas the Saxons first entered history as pirates, and they did not lose their seafaring abilities.

The Rohirrim also differed from the Anglo-Saxons in that they were not several tribes drawn

together. When we speak of the Anglo-Saxons we really are referring to many groups of Saxons

and Angles, as well as the Jutes and some Frisians. The Saxons were a West German people,

related to the Franks, but the Angles and probably the Jutes came from Jutland -- they were

essentially Danes.

In fact, the Danelaw, the region of England that was colonized by the Danish Vikings in the 9th and 10th Centuries, overlapped with almost all of the ancient lands of the Angles.

There are no tribal divisions among the Rohirrim. Nor was Rohan ever divided into many

kingdoms. And the government of Rohan seems to be centered on a stronger monarchy than the

Anglo-Saxons were ever able to establish. In fact, the nearest parallel in Rohan to the great

English Earls would be the Lords of Westfold, of whom Erkenbrand was the one living at the

time of the War of the Ring. Yet he was not only intensely loyal to Theoden, he apparently was

much more under the King's authority than many of the English earls were.

Of course, the Rohirrim developed their entire culture around the use and breeding of horses.

They raised other animals (Eomer makes reference to herds and flocks, so they seem also to have raised sheep and perhaps cattle). But the horse was the center of the Rohirric culture. There was no similar society among the Anglo-Saxons.

The Rohirrim lived in the mountains, too. The Anglo-Saxons were not a particularly

mountainous folk. All of the Rohirric towns and villages were situated in the great valleys, and their refuges were hard to reach. The Anglo-Saxons lived in the lowlands and between the

forests.

The armaments of the Riders of Rohan were also pretty generic. The best description Tolkien

provides of these professional warriors is given in THE TWO TOWERS, when Aragorn, Gimli,

and Legolas first see Eomer's eored (company) approaching them:

-62-

Essays On Middle-earth

Now the cries of clear strong voices came

ringing over the fields. Suddenly they swept

up with a noise like thunder, and the

foremost horseman swerved, passing by the

foot of the hill, and leading the host back

southward along the western skirts of the

downs. After him they rode: a long line of

mail-clad men, swift, shining, fell and fair to

look upon.

Their horses were of great stature, strong and

clean-limbed; their grey coats glistened, their

long tails flowed in the wind, their manes

were braided on their proud necks. The Men

that rode them matched them well: tall and

long-limbed; their hair, flaxen-pale, flowed

under their light helms, and streamed in long

braids behind them; their faces were stern

and keen. In their hands were tall spears of

ash, painted shields were slung at their

backs, long swords were at their belts, their

burnished shirts of mail hung down upon

their knees.

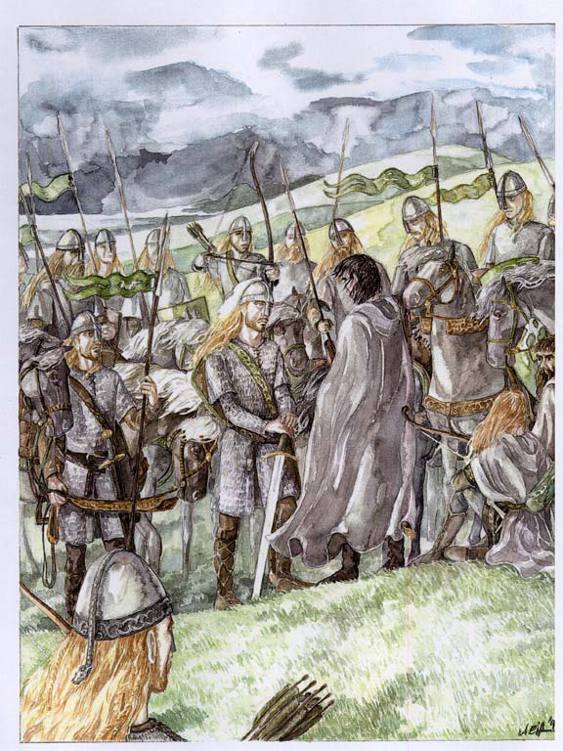

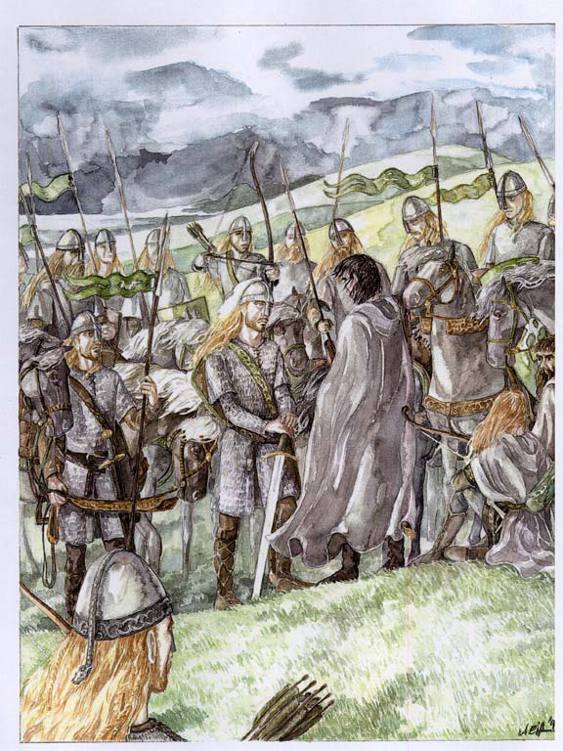

The Riders of Rohan

Copyright © Anke Eissmann. Used by permission.

These are not Anglo-Saxon warriors. They resemble Goths in several ways, and also sound a bit

like Vikings. But their armaments were not atypical for Riders of Rohan. The Rohirrim held a

formal muster and Theoden expected some twelve thousand Riders to assemble (or, rather, said

he could have assembled that many if there had not already been battles in Rohan by the time

Hirgon, the Errand-rider of Denethor, arrived with the Red Arrow of summons).

As for the armaments of Anglo-Saxons, Malcom Todd, a Professor of Archaeology at the

University of Exeter, wrote this in his book, EVERYDAY LIFE OF THE BARBARIANS:

The sword played a relatively minor role in Germanic warfare before the late Roman period, and

even after that time it hardly ranked as the weapon of the common man. Centuries were to elapse before fine Frankish blades were to be highly prized by Viking soldiers….The one-edged slashing weapons of the pre-Roman Iron Age were gradually replaced by two-edged swords, but the

introduction of this more versatile weapon was not accompanied by any significant increase in the number of sword-bearing warriors.

-63-

Parma Endorion

Further on he writes:

It is remarkable that despite fairly frequent contact with Roman frontier armies, and despite

endemic intertribal disputes and private feuds, no great advances were made in armour and arms, with the exception of sword-blades, during the Imperial centuries, Even as late as the sixth

century [500s], the war-gear of the Germans could be unfavourably commented upon.

And:

The Anglo-Saxons Closest of all the Teutonic peoples to the Franks in weapons and tactics were

the Anglo-Saxon settlers in southern England. It has already been noted that, like the Franks and the rest, their use of cavalry was negligible. The offensive weapon of the rank and file was the spear, of which several types are documented, that with a long leaf- or lozenge-shaped head being the best known. These spear-heads commonly measure between 10 inches [about 250 mm] and

18 inches [about 450 mm] in length. The sax was frequently carried by the fifth- and sixth-

century warrior, in Anglo-Saxon England as well as in Frankish Gaul, and was closely, almost

mystically, associated with the Saxon name and race....Body-armour is ill-attested, except for the leading warriors. Helmets are even more rarely mentioned in Anglo-Saxon law than in Frankish,

and only three specimens have been recorded -- all from princely graves. Leather caps may have

protected lesser heads, but probably not many. The shield might be oval or rectangular....

Finally, concerning the use of bows (which Eomer's men used against the Orcs and which many

of the Rohirrim at the Hornburg used), Todd writes:

The bow and arrow, exotic in Merovingian Gaul and Anglo-Saxon England, was more widely

used by other Germans. The Alamanni used a simple D-shaped one-piece bow, and, very rarely, a

bow composed of several different materials. Bone or horn was usually combined with wood in

these composite bows.

In the late Roman period the long-bow put in an appearance in the north. From which part of

Europe this weapon was introduced is unknown but it was not from either the Roman Empire or

from the nomadic peoples. Probably this was something the Germans developed for themselves.

The fact that about 40 long-bows and several bundles of arrows were present in the Nydam

deposit suggests that small units of bowmen may have been used in the later fourth century

specifically against armoured Roman troops. Some of the Nydam arrowheads are narrow and

heavy, and thus well suited to piercing body-armour.

In UNFINISHED TALES Christopher Tolkien reveals too many details concerning the Riders

and the Muster of Rohan to repeat here. It was not, however, a feudal army of either the French or the English design. The Army of Rohan was unlike any army fielded by the Anglo-Saxons,

who used local levies called fyrds to reinforce the main (royal) forces. There were, to be sure,

"local levies" in Rohan, but these were raised only in great need. The Muster of Rohan, divided into three smaller groups, was expected to defend the country.

-64-

Essays On Middle-earth

What About The Burial Mounds outside Edoras?

There was nothing particularly "Germanic" about the funeral mounds of the House of Eorl, let alone of an "Anglo-Saxon" nature. Although the Anglo-Saxons built similar mounds, so did the Scandinavians (many have been excavated at Uppsala in Sweden, and in Denmark), and so did

other Germans, and so did the Celts. In fact, the wagon-burial of Theoden appears to be based on archaeological finds of Celtic wagon-burials from the First Millennium BC.

Many comparisons have been made between the Ship-Burial of Sutton Hoo and Theoden's

burial. There are several problems with such a comparison. For one, Sutton Hoo was first

excavated late in the 1930s just before World War II broke out. Although Tolkien wrote the

passage describing Theoden's burial several years later, there is no mention in his letters or in THE HISTORY OF MIDDLE-EARTH of any connection between the two. The excavation was

thorough but left many unanswered questions, and Tolkien does not seem to have been interested

in those questions (long since answered by subsequent scholarship).

The lack of a ship in Theoden's mound doesn't seem to bother many people since, after all, many ship-burials were only symbolically linked with ships by shaping the mounds into ship contours.

But Theoden's mound isn't so shaped. Although I have called it a "wagon-burial", Tolkien does not state specifically that Theoden's wain was interred in the mound with him. The mound was

raised about a house of stone, which itself is not typical of ship-burials, but does resemble some wagon-burials (most of which were placed in wooden houses).

I should also note here that many people also overlook the significance of what Tolkien wrote in the note I cited above: "a simpler and more primitive people living in contact with a higher and more venerable culture, and occupying lands that had once been part of its domain." At what point in their history did the Anglo-Saxons fit this general description? The Fifth Century AD, when there was still a Roman Empire and the lands they were occupying in Britain were

formerly part of that empire. There is certainly a great deal more contact between the Rohirrim and Gondor than there was between the Anglo-Saxons and Rome, but they were able to observe

what survived of Roman culture through their neighbors the Celts and Franks. Some people

argue that the Rohirrim are like the Anglo-Saxons of the late period, and there are greater

similarities between these two peoples. But culturally the late Anglo-Saxons were no longer on

the periphery of a great civilization, and Tolkien only reluctantly agreed to such a comparison when asked if the Rohirrim resembled the warriors in the Bayeux Tapestry (which depicts how

William of Normandy conquered England):

I have no doubt that in the area envisaged by my story (which is large) the 'dress' of various

peoples, Men and others, was much diversified in the Third Age, according to climate, and

inherited custom. As was our world, even if we only consider Europe and the Mediterranean and

the very near 'East' (or South), before the victory in our time of the least lovely style of dress (especially for males and 'neuters') which recorded history reveals -- a victory that is still going on, even among those who most hate the lands of its origin. The Rohirrim were not 'mediaeval', in our sense. The styles of the Bayeux Tapestry (made in England) fit them well enough, if one

remembers that the kind of tennis-nets [the] soldiers seem to have on are only a clumsy

conventional sign for chain-mail of small rings.

-65-

Parma Endorion

Mail was an ancient armorial tradition, having been developed in the southern Mediterranean

region around the Third Century BC. Germanic warriors who served in the Roman Empire,

including the Goths, wore such armor and the styles of the Rohirrim need not wait for the

Eleventh Century AD to find precedence in history.

So, in conclusion, there was very little similarity between the Rohirrim and the historical Anglo-Saxons with which Tolkien was so familiar. The Rohirrim were idealized Northmen, a romantic

people intended to convey the best traditions from myth, legend, and history of a northern people who were no better and no worse than other men.

NOTE: Tom Shippey, in THE ROAD TO MIDDLE-EARTH, argued that Tolkien really did

base the Rohirrim on the Anglo-Saxons:

This led him, indeed, into yet further inconsistencies, or rather disingenuousnesses. Tolkien was obliged to pretend to be àtranslator'. He developed the pose with predictable rigour, feigning not only a text to translate but behind it a whole manuscript tradition, from Bilbo's diary to the Red Book of Westmarch to the Thain's Book of Minas Tirith to the copy of the scribe Findegil. As

time went on he also felt obliged to stress the autonomy of Middle-earth -- the fact that he was only translating analogously, not writing down the names and places as they really had been, etc.

Thus of the Riddermark and its relation to Old English he said eventually 'This linguistic

procedure [i.e. translating Rohirric into Old English] does not imply that the Rohirrim closely resembled the ancient English otherwise, in culture or art, in weapons or modes of warfare,

except in a general way due to their circumstances...' (III, 414).

But this claim is totally untrue. With one admitted exception, the Riders of Rohan resemble the Anglo-Saxons down to minute details. The fact is that the ancient languages came first. Tolkien did not draw them into a fiction he had already written because there they might be useful, though that is what he pretended. He wrote the fiction to present the languages, and he did that because he loved them and thought them intrinsically beautiful. Maps, names and languages came before

plot. Elaborating them was in a sense Tolkien's way of building up enough steam to get rolling; but they had also in a sense provided the motive to want to. They were 'inspiration' and

ìnvention' at once, or perhaps more accurately, by turns.

Professor Shippey should know better. In fact, as I have shown above, there is no distinct

reference to the Anglo-Saxons in Rohirric culture. That is, virtually nothing which is uniquely an Anglo-Saxon custom or trait is to be found in the Rohirrim. Numerous elements in Tolkien's

depiction of the Rohirrim are far more easily identifiable with other peoples, including the Goths and Scandinavians (both of whose literature Tolkien studied extensively and knew intimately, a

fact Professor Shippey does not concede in his elaborate argument):

Thus 'Rohan' is only the Gondorian word for the Riders' country' they themselves call it 'the

Mark'. Now there is no English county called 'the Mark', but the Anglo-Saxon kingdom which

included both Tolkiens' home-town Birmingham and his alma mater Oxford was 'Mercia' - a

Latinism now adopted by historians mainly because the native term was never recorded. However

the West Saxons called their neighbours the Mierce, clearly a derivation (by ì-mutation') from

Mearc; thèMercians' own pronounciation of that would certainly have been thèMark', and that

was no doubt once the everyday term for central England. As for the 'white horse on the green

field' which is the emblem of the Mark, you can see it cut into the chalk fifteen miles from

-66-

Essays On Middle-earth

Tolkien's study, two miles from 'Wayland's Smithy' and just about on the borders of 'Merica' and Wessex, as if to mark the kingdom's end. All the Riders' names and language are Old English, as many have noted;*but they were homely to Tolkien in an even deeper sense than that.

Professor Shippey should not rely upon such a flimsy argument. "Mark" comes from a very common ancient Germanic word which survived on the continent. "Mark" means "march", or borderland. The Mercians were a border folk, living between the other Angles and Saxons and

the Welsh (the "foreigners", the remaining Celts who had been driven to the western regions of Britain by the invading Germans). Tolkien's use of the word "Mark" for the Rohirrim's own designation of their country is a clear extension of the ancient Germanic custom for using this term of a border region. The titles of nobility such as Margrave, Markgraf, and Marquess all

retain the "mark-" element, referring to a March Count, a borderland count. A count was originally a military officer appointed by a king to defend a region of the country, and the title was derived from Roman tradition (as in the Count of the Saxon Shore, a military office charged with defending southern Britain against sea borne Saxon raids):

As has already been remarked, though, the Riders according to Tolkien did not resemble the

'ancient English...except in a general way due to their circumstances: a simpler and more

primitive people living in contact with a higher and more venerable culture, and occupying lands that had once been part of its domain'. Tolkien was stretching the truth a long way in asserting that, to say the least! But there is one obvious difference between the people of Rohan and the àncient Engl