CHAPTER IV.

AGAINST HIS WILL.

“I beg your pardon for disturbing you, but I think you must belong to the British Mission to Ethiopia?”

The speaker was a hot and dusty lady, mounted on a sorry pony, who had halted in front of the hotel at Bab-us-Sahel, the port of Khemistan, in which Sir Dugald Haigh’s party were quartered. Dick North, who had been reclining in a cane chair on the verandah, with a cigar and a wonderfully printed local paper, jumped up when he heard the voice.

“I am a member of the Mission,” he answered. “Can I do anything for you? I am sorry that Sir Dugald Haigh is out, but perhaps you would prefer to wait for him? Won’t you come in out of the sun?”

“Thanks,” said the lady, dismounting nimbly before he could reach her, and giving the bridle to a youthful native groom who had accompanied her, “but I need not trouble Sir Dugald Haigh. Please tell me whether it is true that there is a lady doctor in your party?”

“Yes. Miss Keeling is her name.”

The lady uttered an exclamation of delight.

“Oh, that is just splendid! I must see her at once, please. My name is Guest; she will remember me if you tell her that Nurse Laura is here. I was a probationer at the Women’s Hospital when she was house-surgeon there, and we knew each other well. Please ask her to see me at once: it is a matter of life and death.”

Drawing forward a chair for the lady, Dick departed on his errand, and returned presently with Georgia, who had been resting in her room after a long ride in the morning. Miss Guest jumped up to meet her.

“Oh, Miss Keeling, it is such a relief to find you here! I want you to come with me at once, to see a poor woman who is most dangerously ill. I will tell you about it while you get your things together. There is not a moment to lose.”

The two ladies vanished round the corner of the verandah, and returned in a few minutes, Georgia wearing her riding-habit and carrying a professional-looking black bag.

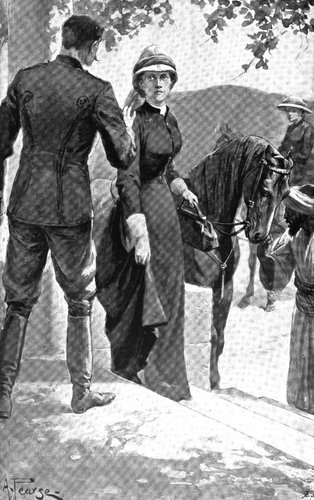

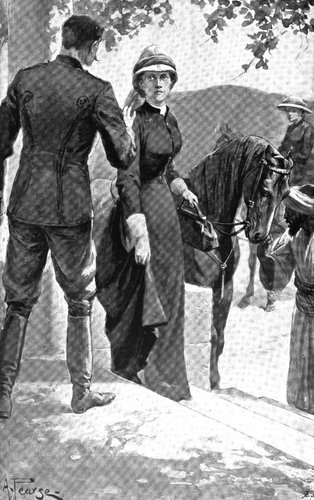

“Would you be so kind as to tell them to put my saddle on a fresh horse for me, Major North?” she said, briskly. “I am afraid we are losing time.”

“What is it you are proposing to do?” asked Dick, after calling one of the native servants and giving him the order.

“Miss Keeling is going to ride out with me to our summer station,” explained Miss Guest, volubly. “Missionaries are not permitted to reside in Khemistan except in Bab-us-Sahel itself, you know, but the Government allows us to rent a small house in a village five miles off for the hot weather. This poor young woman is the wife of one of our native converts there, the son of the principal landowner.”

“But do you mean that Miss Keeling is to ride five miles in this heat, when she is tired already?” demanded Dick. “It is preposterous!”

“I should not think of asking her to do it if it was not so important,” said Miss Guest. “You see, I have ridden all the way in, and I am going out again with her.”

“You will be down with sunstroke to-morrow,” said Dick to Georgia. “Wait until it is a little cooler, and I will hunt up some sort of cart and drive you out.”

“We can’t afford the time,” said Georgia.

“No, indeed,” said Miss Guest; “I scarcely dared to come away myself. Happily, I was able to leave dear Miss Jenkins with the poor woman. She has such wonderful nerve! I believe she would have attempted the operation herself if only we had had the proper appliances.”

“It is a very good thing you had not,” murmured Georgia, grimly.

Dick glanced at her, hoping that she was giving way.

“Headlam will be back in another half-hour,” he said. “He has had plenty of experience, and he will be delighted to go out and see the woman.”

“Oh, but you don’t know Khemistan,” said Miss Guest, quickly. “Surely you must have forgotten that a gentleman would never be admitted into the women’s apartments.”

“I thought you said the people were Christians?” said Dick, taken aback.

“The husband is, but the wife has not been baptised, and is still in her father-in-law’s house. They are most bigoted people, and regard this as a kind of test case. Every one has been dinning into the poor young man’s ears that his wife’s illness is a judgment upon him for becoming a Christian, and his faith is beginning to waver. ‘What can these Christians and their Christ do for you?’ they ask him. He is terribly tried, and though Miss Jenkins and I have done everything we could think of for the poor girl, it was no good. Then we heard of the arrival of the Mission, and it suddenly flashed into my mind that I had seen something in a paper from home about a lady doctor who was to accompany it, and I rode over here at once, and found Miss Keeling, of all people. It was a real answer to prayer,” and Miss Guest’s voice faltered, and the tears rose in her eyes.

“Oh, when are they going to bring that horse?” said Georgia, impatiently.

“I hear it coming now,” said Dick. “But let me drive you over, Miss Keeling; it won’t be so fatiguing for you, and I am sure I can borrow a cart from some one very soon.”

“I can’t lose another minute,” said Georgia. “No, thank you, Major North, we must not wait.”

“But just tell me when you are likely to be ready, that we may send a carriage to fetch you.”

“I can’t tell. These cases vary so much. I shall probably be obliged to remain at the village all night.”

“But this is absurd! You are throwing away your health. What does this woman signify to you?”

“It is my professional duty to attend any one who summons me,” said Georgia, giving him an indignant glance; “even if there were no special reasons connected with this case.”

“It is my professional duty to attend any one who summons me,” said Georgia, giving him an indignant glance.

“Well, if you will do these ridiculous things, I can’t help it!” said Dick, angrily. “I suppose you will have your own way.”

“I think it extremely probable that I shall,” retorted Georgia. “No, thank you, I won’t trouble you—I can mount alone.”

With an intensity that would have seemed laughable to himself under any other circumstances, Dick longed that she might find the feat impracticable; but she beckoned to the groom to bring the horse to the verandah steps, and, mounting with great agility, rode away with Miss Guest, who had been staring with round eyes at the “horrid sneering officer,” as, after this day’s experience, she persisted in denominating Dick.

As for Dick himself, he shrugged his shoulders as he looked after the two ladies, and went away to Stratford’s room to relieve his mind. Stratford, who was lying on his bed reading, looked up in surprise as he entered.

“I thought I had left you comfortably established on the verandah?” he remarked.

“I was driven away by an invasion of the Amazons,” said Dick, gloomily, taking a seat on the table, where he smoked in silence for a few minutes. “If there is one kind of creature I bar and detest above all others”—he burst out suddenly—“it’s the New Woman!”

“Have you met one?” inquired Stratford, with deep interest. “I always thought it was a case of ‘much oftener prated of than seen?’”

“There’s no need to go about looking for specimens,” returned Dick. “We’ve got one with us, worse luck!”

“You have been getting the worst of it in an argument again, haven’t you?” asked Stratford, genially.

“What in the world has that to do with it? I don’t want any of your chaff. It ought to be made penal for any woman to enter any trade or profession practised by men.”

“Good gracious! would you add the attraction of forbidden fruit? Still, I don’t say that your plan isn’t worth considering. The penalty would be death, I suppose, and it might redress the inequality of the sexes a little.”

“Oh, hang it all, Stratford!” cried Dick, flinging away his cigar, “I’m serious. It makes me perfectly sick to see these women parading their independence of men, and glorying in what they know, and ought never to have learnt. It’s bad enough when they are strangers, and you don’t care a scrap about them, but when it comes to a girl you’ve known——”

“Better not go on, old man,” said Stratford. “You may say more than you mean, and be sorry for it when you are cooler.”

“I can’t help it. I know I’m safe with you. Now I put it to you: can a man be cool when he sees a girl he knew years ago—his sister’s friend—turning into one of these unsexed women, of whom the less that is said the better? One would rather see her in her grave!”

“You are a little out of sorts,” said Stratford, with imperturbable calmness, “and you are making mountains out of molehills. I won’t pretend not to know what you are driving at, but I do say that I think you are using most unwarrantable language—— Hullo! who’s there? Come in.”

This was in answer to a knock at the door, which opened immediately, and admitted Fitz Anstruther. The young fellow’s hands were clenched and his face flushed, and it was apparent to the two men that he was hard put to it to restrain an outburst of furious passion.

“I wasn’t listening,” he said, hastily, “but I couldn’t help hearing what you were saying. These beastly rooms——” He broke off suddenly, and his hearers, perceiving that the side walls only reached within some six feet of the roof, realised that their conversation must have been audible to any of their neighbours on either side who chanced to be in their rooms. “But that’s neither here nor there,” he went on. “I heard you blackguarding Miss Keeling’s name in the most shameful way, and I am not going to listen to it.”

“I was not aware that we had mentioned the name of any lady,” said Stratford. Fitz was taken aback for a moment, but recovered himself speedily.

“It wasn’t you, it was Major North,” he said, glaring at Dick. “He mentioned no names, but if he can assure me he wasn’t speaking of Miss Keeling, I’ll apologise at once. You see? I knew he could not do it. Now look here, Major North—you are my superior, and I know you can ruin me if you like, but I won’t hear Miss Keeling spoken of in that way.”

“Your hearing what you did was quite your own affair,” said Dick, coolly. He had an enormous advantage over Fitz, for the sudden attack had restored him to his usual calmness, but the boy did not flinch.

“I know, but I can’t help that. You may be sure I wouldn’t have listened to it of my own accord, but when you talked as you did, it naturally forced itself on my hearing, and a nice hearing it was! Miss Keeling has no one here to look after her, and if you are cad enough to take advantage of that, I’ll do what I can. If you dare to say that she isn’t every bit as good and as gentle as your own sister, I tell you to your face you’re a liar.”

“Anstruther!” cried Stratford, sitting up suddenly, “do you know what you are saying? For your own sake and the lady’s be quiet.”

“I can’t help it,” repeated Fitz. “Miss Keeling has been awfully kind to me, and I’m not going to hear her insulted. You can do what you like, Major North. If you want to fight, I’m ready.”

“Young idiot! who wants to fight you?” growled Dick, lounging to the door with his hands in his pockets. “I didn’t know you were going to hold a levée, Stratford. I think I’ll leave you to train the young idea for a little.”

“You haven’t answered me,” said Fitz, doggedly, barring his passage; but Stratford interposed again.

“Have the goodness to sit down on that chair, young Anstruther. I want a straight talk with you.” The boy obeyed sullenly, and Stratford went on. “As you are in my department, I suppose it falls to me to ask you, now that North is gone, whether you think you have done a very fine thing?”

“I don’t think about it at all,” was the uncompromising response, “but I know I should have been a cad not to have done it.”

“Let us just consider what it is you have done,” said Stratford. “You hear North and myself engaged in private conversation, and you thrust yourself into it uninvited.”

“If it had been private I shouldn’t have heard it,” retorted Fitz.

“Well, it was intended to be private, at any rate. Couldn’t you have gone away, or have let us know that you were listening?”

“That’s what I would have done, certainly, if it hadn’t been for what North said. I couldn’t stand that.”

“No? and you felt bound to come in and tell us so. Now, Anstruther, I am going to speak to you as a friend. When you are a little older, you will know that men of the world—gentlemen—are not in the habit of bringing the names of ladies into a discussion. If they differ in opinion on some subject of this kind, they contrive to quarrel ostensibly about something else.”

“And you would have me let Major North say the vile things he was doing about Miss Keeling for all the hotel to hear, and yet pretend to take no notice?”

“Allow me to remind you that North mentioned no names. Any listener could only at best have made a guess at the identity of the lady in question, until you came in and published her name.”

Fitz’s face was turning a dull red, and he said nothing. Stratford saw his advantage, and followed it up.

“You ought to be very thankful that there are so few people about just at this time. If the place had been full, you might have done terrible harm. It would have been quite possible to remonstrate with North on general grounds, if you felt called upon to do it, without mentioning any names or calling anybody a liar, but to march in and identify a particular lady as the one of whom these things had been said, was unpardonable. So was the way in which you did it. Of course, I don’t know what your ideas as to duty and discipline may be, but it does not seem to me your business to reprove North at all.”

“I wouldn’t have done it, except in this case,” said Fitz, eagerly. “I know he has led a rough life, and I can put up with a good deal from him, but when it comes to behaving like a cad to a lady, I had to speak.”

“And who gave you the right to make excuses for your superiors, or to bring accusations against them?” demanded Stratford, in a tone which made the youthful censor shake in his shoes. “I think you have forgotten the position North holds, and the way in which he gained it. Any man in Khemistan would laugh at you if you told him that Dick North had been rude to a lady. He is one of the most chivalrous fellows that ever breathed. You may not know that when Fort Rahmat-Ullah was relieved, and the non-combatants conducted back into safety, North gave up his horse to a Eurasian clerk’s wife who had a sick child, and walked all the way himself.”

“I can’t make it out,” said Fitz, hopelessly.

“You see that it doesn’t do to judge a man merely on the strength of a momentary impression, then? Well, I will tell you in confidence what really happened this afternoon. It was this very chivalry of North’s which got him into trouble. You know that the lady of whom mention has unfortunately been made is very independent, and I gather that she persisted in refusing all North’s offers of help in some business or other. That hurt his feelings, and he came to my room to have his growl in peace, with the result you know. I don’t say he was right, but I do say you were wrong.”

“I’m awfully sorry,” said Fitz. “I will apologise, Mr Stratford, if you say I ought.”

“I don’t think it is advisable to make more of the matter. I will undertake to convey your sentiments to North, if you like.”

“Thank you; and perhaps I had better apologise to Miss Keeling too?”

“No!” Stratford almost shouted. “How old do you consider yourself, Anstruther? Twenty? I shouldn’t have thought it. Your ideas are what one might expect of a boy fresh from a dame’s school. You must learn never under any circumstances to trouble a lady about any affair of the kind. I really did not expect to have to undertake infant tuition when I started on this journey. If you have made a fool of yourself, don’t go and make things worse by worrying Miss Keeling.”

“I’m awfully sorry,” murmured Fitz again. “Thank you for what you have been telling me, Mr Stratford. I wish I hadn’t said what I did to Major North, and yet I know I should do it again if I heard him talking like that, and I feel I ought to do it too.”

“Your ideas are mixed,” said Stratford. “You had better go away and think things out a little by yourself,” and Fitz departed obediently.

Georgia did not return to the hotel again that evening. Dick, appealed to by Lady Haigh as the member of the party who had last seen her, said that he believed she had gone out into the country with some lady missionary or other, and might not be back until the next day. The news drew from Sir Dugald a mild lamentation to the effect that he really thought they had done with missionaries when they left Baghdad, a remark for which he received a reproof from Lady Haigh afterwards in private.

“I wish you would not say that kind of thing before these new young men, Dugald. They don’t know how kind you were to the missionaries at Baghdad, and they may think you mean it,” a charge to which Sir Dugald offered no defence. It was by means of rebukes of this kind that Lady Haigh kept up the fiction dear to her soul that she ruled her husband with a rod of iron, and guided him gently into the paths it was well for him to take; whereas those who watched the pair were of opinion that Sir Dugald’s was emphatically the ruling spirit, and that his mastery in his own household was so complete that he could afford to allow his wife to think otherwise without making any protest.

In spite of Dick’s careless and positive words to Lady Haigh, it might have been observed that he lingered on the hotel verandah later than any one else that night, and that he appeared there again at a most unearthly hour in the morning, wearing the haggard and strained aspect characteristic of a man who has slept only by fits and starts, owing to the fear of oversleeping himself. One who did not know the circumstances of the case might have said he was there watching for some one, but that would have been manifestly absurd. Whatever might be the cause of his unusual wakefulness, he was occupying his place of the day before when the creaking and groaning of wheels, gradually coming nearer, announced an arrival. A few minutes later, as Georgia, tired and exhausted, descended from the missionaries’ bullock-cart, which was wont to convey Miss Jenkins and Miss Guest, in company with a miniature harmonium, a stock of vernacular gospels, and occasionally a native Bible-woman, on their itinerating tours among the villages around, she discovered him waiting to receive her. She was so tired that she had dozed unconsciously in the bullock-cart, in spite of the rough music of the wheels and of the appalling jolts; and now, awakened suddenly by the cessation of both sound and motion, she stood shivering and blinking in the grey twilight, a sadly unimpressive figure. Dick mercifully forbore to look at her as he took the bag from her hand and helped her up the steps, then settled her in his chair and shouted to the servants to hurry with the doctor lady’s coffee. Georgia tried to protest feebly, but he was adamant.

“You must have something to eat before you go to bed, or we shall have you down with fever this evening. You will allow me to know something of the climate of Khemistan, I hope, though I am not a ‘professional’ man.”

There was an unconscious emphasis on the adjective, which showed Georgia that coals of fire were being heaped upon her head in return for her words of the day before. But she did not respond to the challenge, for she was too much exhausted for a war of words; and, moreover, the coffee was very acceptable, even though it was Major North to whom she owed it. When the sleepy and unwilling servants had made and brought the coffee, however, she paused before tasting it.

“I can’t argue with you now, Major North, but I just want to say this. It was worth while going through all the training, and some of it was bad enough at the time, simply for the sake of this night’s work. If I never attended another case, I should be glad I was a doctor, if only to remember the happiness of those poor Christians in that village.”

“I wasn’t aware that I had attempted to argue,” said Dick, who was busily cutting what he imagined was thin bread and butter. “There, eat that, Miss Keeling. The woman didn’t die, then?”

“No, I hope she will do well. The people, heathen and Christians alike, took it as a miracle. If it helps Miss Guest and Miss Jenkins in their work, I shall be so thankful.”

“Time enough to consider that afterwards,” said Dick, as Georgia put down her cup and sat gazing into the twilight. “If it helps you to an attack of fever, you won’t be thankful, nor shall I. By the bye, what happened to your horse? I hope you didn’t meet with an accident?”

“Oh no, but I was so dreadfully sleepy that I was afraid to ride, and the ladies lent me their bullock-cart. They are to send the horse back later in the day. You mustn’t think that I am generally so much overcome by sleep after spending a night out of bed as I am now. When I was in hospital I thought nothing of sitting up. It is simply that I am out of practice.”

“Of course,” said Dick, politely, suppressing the retort he would infallibly have made had things been in their normal condition. It was so pleasant to be caring for Georgia in this way, without feeling the slightest desire to quarrel with her, that he began to wish she would be called out every night by her professional duties. What did his own broken slumbers signify? At any rate, he had stolen a march on that young fool Anstruther now. He had not thought of seeing that Miss Keeling had something to eat when she came in. And Dick caught himself afterwards recalling with something like tenderness, a feeling which was obviously out of the question, the pressure of Miss Keeling’s hand as she shook hands with him before going indoors, and the tones of her voice as she said—

“Thank you so much, Major North. It was most kind of you to take all this trouble for me. I hope you won’t be very tired after getting up so early.”

“Oh, I just happened to be out here. I didn’t sleep very well,” he explained, airily, and went off well satisfied with his own readiness of resource, not dreaming that Georgia, in her own room, was saying bitterly to herself as she took down her hair—

“He need not have told me so particularly that he didn’t get up because of me. I knew he did not, of course, but it wasn’t necessary for him to say it. Well, I shall not presume upon his kindness, although he is afraid I may.”

The natural consequence of this deceitful excess of candour on Dick’s part was, that when he met her next, he found that he had lost any ground which his ready services might have gained for him in Miss Keeling’s estimation. For him the events of the early morning had cast a glamour over the rest of the day, and when he saw Georgia again towards evening, he was prepared to meet her with the friendliness natural between two people who had found the barrier of prejudice which separated them partially broken down. But she received him with the easy graciousness she would have shown to the merest acquaintance, expressing her gratitude for his kindness, indeed, but ignoring entirely the approach to something like intimacy which he thought had been established between them. Dick was not accustomed to be repulsed in this way, and when he overheard Georgia telling Sir Dugald how fortunate it had been for her that she found Major North up when she returned, and how kind he had been in getting her some coffee, his wrath, if not loud, was deep. She was betraying what he liked to think of as a secret known only to their two selves, and making an ass of him before the other fellows. This led him to remember that, after all, circumstances were unchanged. Georgia was still a doctor, and displayed no symptoms of being convinced, whether against her will or otherwise, by his arguments against the existence of medical women, or of discontinuing the practice of her profession. Nay more, Dick was beginning to see that it was unlikely she would ever be so convinced, and that if there was to be peace between them it must be on the basis of acquiescence in facts as they were. Hence, as he was still determined under no circumstances to extend even the barest toleration to lady doctors, it is not surprising that Dick felt himself a much injured man, and that his soul revolted a dozen times a-day against the conclusions at which he had been forced to arrive.

As for Georgia, she continued to take pains to show him that she quite understood his view of the case, which she did not, and devoted herself largely to itinerating in the country round with Miss Jenkins and Miss Guest. She was welcomed on account of her medical skill in many places where they had not been able to gain a footing, and had the pleasure of knowing that she left these houses open to her friends for the future. The work proved to be so interesting that she was very sorry to leave it, and on the eve of departure she confided to Lady Haigh the resolution she had definitely formed to come back to Bab-us-Sahel when the Mission returned from Kubbet-ul-Haj, and to settle down with Miss Guest and Miss Jenkins.

“Nonsense, Georgie! you mustn’t throw away your talents like that,” cried Lady Haigh, aghast.

“But I should only stay here until they would allow me to settle on the frontier, of course,” said Georgia.

“I wish General Keeling were alive,” said Lady Haigh, irritably. “He would very soon put a stop to these absurd schemes. Or I wish you were married. That would do as well.”

“But if that is one reason for my not marrying?” asked Georgia.