CHAPTER VI.

AN OFFER OF CO-OPERATION.

“The King of all Kings, the Upholder of the Universe, places this hovel at the disposal of his high eminence the Queen of England’s Envoy, and entreats that he will deign to use it as his own,” said the sleek official who had been deputed to meet the travellers and bring them into the town, as he paused opposite the doorway of a large house and indicated with extended hand that the end of the journey had been reached.

“In other words, this imposing building is to be our residence for the present,” said Sir Dugald, riding into the courtyard and turning round. “Allow me to welcome you to Kubbet-ul-Haj, ladies.”

“It is not as good as Baghdad,” said Lady Haigh, looking round disparagingly on the whitewashed walls; “but I daresay we shall be very comfortable. After all, it won’t be for long.”

“Express my thanks to the King,” said Sir Dugald pointedly to the messenger, “and tell him that the pleasantness of our quarters will make us anxious to prolong our stay in his city.”

The official, well-pleased, stayed only to point out the entrance to the second courtyard of which the house boasted, and to intimate that if the accommodation provided should prove to be too limited, another house could easily be secured, and then took his departure; while the new arrivals passed under an archway into the inner court, to find facing them the chief rooms of the establishment. These were evidently intended as Sir Dugald’s quarters, and Lady Haigh surveyed them with high approval.

“Come!” she said. “We shall not be so badly off after all. I was beginning to be afraid we should be as much crowded as you were at Agra in the Mutiny, Dugald. I think the rooms on that side will do nicely for you, Georgie.”

“I don’t know whether you will all be able to find quarters in the first block of buildings, gentlemen,” said Sir Dugald to his staff when he had helped his wife and Georgia to dismount, and they had gone indoors to explore. “I must have Mr Kustendjian there, for he may be wanted at any moment, and I doubt whether that will leave you rooms enough.”

“If any one has to seek quarters outside, I hope I may be the favoured man,” said Dr Headlam. “Judging by the sights I saw as we came through the streets, and the cries for medicine which were addressed to me, there is an enormous amount of disease here, and I shall have my hands pretty full if I begin to try any outside practice. I think I am justified in believing that you would approve of such a course, Sir Dugald? It could only make the Mission more popular.”

“By all means, if you wish it; but don’t wear yourself out with doctoring all Kubbet-ul-Haj, and forget that you came here as surgeon to the Mission. You think you will do better if you are lodged outside?”

“Well, I didn’t quite like the idea of bringing all the filth and rascality of Kubbet-ul-Haj into the Mission headquarters, but that would remove the objection. I think it would be both safer and more agreeable for all of us if you would allow me to camp in some other house.”

“Then perhaps you could take that collection of yours over to your new quarters as well as your other belongings? It is not altogether the most delightful of objects.”

“Either as to sight or smell,” put in Dick North. “Those beasts you have preserved in spirits are enough to give a man the horrors, doctor.”

“Oh, our much-maligned masterpieces shall share my quarters, by all means,” said the doctor. “If Miss Keeling breaks her heart over parting with the collection, don’t blame me.”

“Miss Keeling will probably bear the loss with equanimity,” said Sir Dugald. “Natural history collections are not exactly ladies’ toys. At any rate, if she is uneasy about the state of her pet specimens you can bring her bulletins respecting them at meal-times. We shall see you as usual at tiffin and at dinner, I suppose, doctor? And you know that Lady Haigh is always glad to welcome you at tea.”

“I shall certainly not decline such an invitation in favour of solitary meals hastily partaken of amongst the specimens,” said Dr Headlam.

“Then we may consider that settled,” said Sir Dugald. “I think we may regard ourselves as fairly fortunate in our quarters here. What is your opinion, Stratford?”

“I think the place is very well adapted for our business, certainly,” returned Stratford. “The general public will only be admitted to the outer court, I suppose?”

“Yes; the large room on the ground-floor of your quarters will serve as our durbar-hall,” said Sir Dugald, “and the attendants of the Ethiopian officials can remain on the verandah. This inner court must be sacred to the ladies, so that they may go about unveiled. No Ethiopian can be allowed to cross the threshold without an invitation, and only those must be invited who know something of English usages and will not be shocked by what they see. The raised verandah before the house will no doubt serve as a drawing-room. What do you think of the place, North?”

“Good position for defence,” said Dick, meditatively. “You hold the outer court as long as you can, and then fall back upon the first block of buildings. When that becomes untenable, you blow it up and retire upon the second block.”

“Until you have to blow that up too, and yourself with it, I suppose?” said Sir Dugald. “For the ladies’ sake, I must say I hope we shall not have to put the defensive capabilities of the house to such a severe test. Well, gentlemen, we shall meet at dinner. No doubt you will like to get your things settled a little. Your own servants will be able to find quarters in your block, but the rest must occupy the buildings round the outer court.”

When Sir Dugald had thus declared his will the party separated, the staff proceeding to their quarters in Bachelors’ Buildings, as the first block was unanimously named, and allotting the rooms among themselves on the principle of seniority; while the doctor went house-hunting with the aid of a minor official who had been left in the outer court to give any help or information that might be needed. Under his auspices a much smaller house, only separated from the headquarters of the Mission by a narrow street, was secured, and hither Dr Headlam removed with his servants and the famous collection. When the members of the Mission met at dinner they had shaken down fairly well in their several abodes, and after a little inevitable grumbling over accustomed luxuries which were here unattainable, they displayed a disposition to regard the situation with contentment and the rest of mankind with charity. Sir Dugald noted down certain points on which it would be necessary to appeal for assistance to the urbane gentleman who had instituted the party into their habitation, while Lady Haigh promised help in matters which could be set right by feminine intuition and a needle and thread, and peace reigned at headquarters.

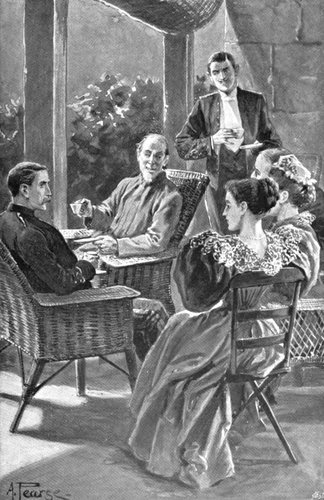

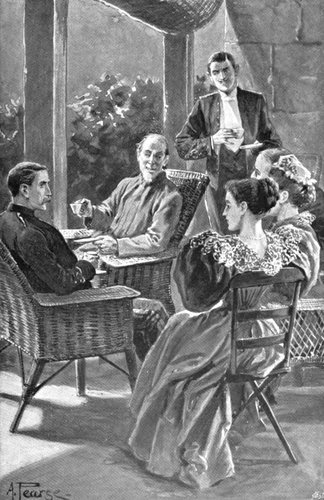

It was not until dinner was over and the members of the Mission were partaking of coffee on the terrace, with the lights of the dining-room behind mingling incongruously with the moonlight around them and outshining the twinkling lamps visible here and there in the loftier habitations outside the walls of the house, that an interruption occurred, and the quiet was broken by the entrance of Chanda Lal, Sir Dugald’s bearer, with a visiting-card, which he handed to his master on a tray.

“What’s this, bearer?” asked Sir Dugald, impatiently.

“Highness, the sahib bade me bring it to you.”

“The sahib? Here? In Kubbet-ul-Haj? Who is he? What is he doing here?” Sir Dugald’s brow was darkening ominously.

“Highness, I know not. I said that the burra sahib received no visitors this evening, and the sahib said, ‘Take this to your burra sahib, and tell him that my name is Heekis, and that I wish to see him.’”

“‘Elkanah B. Hicks. “Empire City Crier,”’” read Sir Dugald from the card in his hand in a tone of stupefaction. “In the name of all that is abominable!” he cried, with lively disgust, “it’s a newspaper correspondent, and an American at that, and here before us!”

“I know the name,” said Stratford. “Hicks was the ‘Crier’ correspondent who made himself so prominent over the Thracian business. He was arrested and conducted to the frontier while the second revolution was going on.”

“The very worst kind of busybody!” said Sir Dugald, wrathfully. “I only wish that Drakovics had shot him when he had him safe. What does he mean by poking himself in here?”

“He is in search of marketable ‘copy,’ without a doubt,” said Stratford, “and he is taking the most direct way to get it. He has a fancy for talking and behaving like a sort of semi-civilised Artemus Ward, which takes in a good many people; but he is considered about the smartest man on the ‘Crier’ staff, and that is saying a good deal.”

“Whatever his fancies may be,” growled Sir Dugald, “I don’t see that they are any excuse for the man’s thrusting himself upon me out of business hours without the ghost of an introduction.”

“Still, dear,” said Lady Haigh, “we had better have him in and be friendly to him. In a place like this white people are bound to hang together, and I dare say we shall find him very pleasant.”

“Bring the sahib in,” said Sir Dugald, shortly, to Chanda Lal, adopting his wife’s pacific suggestion, but without any lightening of countenance; and presently the bearer ushered in a lank, sallow man, rather over middle age, with a straggling lightish beard, and hair that seemed to stand somewhat in need of the scissors. As Fitz said afterwards, if he had only worn striped trousers and a starred waistcoat, Mr Hicks would have represented to the life the Brother Jonathan of American, not English, caricaturists. Sir Dugald received his visitor with frigid politeness, and the staff, taking their cue from him, did the same; but Mr Hicks appeared to feel no embarrassment, although the tender hearts of Lady Haigh and Georgia were moved to pity on his account. He was duly supplied with coffee; and when Georgia had passed him a plate of cakes he stretched his long limbs comfortably as he reclined in a cane chair and beamed upon the party.

“It makes one feel real high-toned,” he said, slowly, “to be waited upon out here at the back of creation by two lovely and cultured daughters of Albion.”

Sir Dugald gave him a stony glance in reply; while the younger men, uncertain whether the remark was to be considered as due to deliberate rudeness or to ignorance, wavered between amusement and indignation. Lady Haigh answered pleasantly but coldly—

“We are not accustomed to be treated to quite such elaborate compliments, Mr Hicks; but no doubt American manners differ from ours. So I have always understood, at least.”

“You bet they do, ma’am!” was Mr Hicks’ reply, delivered with almost startling emphasis. “When your nigger let me in just now, and the General there stepped forward and said, ‘Mr Hicks, I presume?’ hanged if I didn’t think I had got into a Belgravian drawing-room, or into Central Africa with Stanley, instead of finding a party of civilised white people in the midst of Ethiopia! I guess I’m not cut out for shows of this kind, any way.”

“You prefer a European post, perhaps?” suggested Stratford, as Sir Dugald remained silent.

“You may consider that proved, sir, some! I can fly around with any man in a civilised country, and back myself to send home more ‘copy’ than the paper can use; but I was a fool to cable back ‘Done!’ when the Editor wired, ‘Can you start for Ethiopia next week, and keep an eye on this Mission business?’ Set me down in a telegraph bureau, with a dozen newspaper men there before me and only one wire, and I’ll bet you my bottom dollar that my despatch will go over that wire before any of the other fellows’; but when it comes to organising a dromedary-service to carry my ‘copy’ week by week, it makes me tired of life.”

“If you find it so hard to send your letters, how did you surmount the difficulties of getting up here yourself?” asked Sir Dugald, with a faint appearance of interest.

“I must confess to getting along by taking your name in vain, General,” returned Mr Hicks, easily. “I travelled around for a week or two in Khemistan, just to throw your frontier people off the scent and to make friends with some of the natives. They smuggled me across into Ethiopia in disguise, and I told the people here that I was sent out to write about the Mission and note how it was received, which was quite true. Consequently I was taken everywhere for an emissary of your Government, which has smoothed the way for me considerably. I guess it will gratify you to know that your name was a passport most everywhere.”

“Having heard you were a newspaper correspondent,” said Sir Dugald, “I might have guessed what your methods would be.”

“We military people,” said Lady Haigh, again interposing as peacemaker, “have an odd prejudice against special correspondents, Mr Hicks. It is awkward, but you must be kind enough to excuse it.”

“It’s nothing to what I should feel if I was in the General’s place, ma’am,” said Mr Hicks, affably. “I wouldn’t have one in my camp for any money. They might pillory me throughout the Press of the Union, but so long as I kept them off I should smile. Now, General, after that handsome acknowledgment, I hope we are friends?”

“It’s nothing to what I should feel if I was in the General’s place, ma’am,” said Mr Hicks, affably.

“I hope so,” returned Sir Dugald, still unsoftened.

“I should like to do a deal with you, General,” continued Mr Hicks. “If you could spare me a minute or two alone, I think I could convince you that we have interests in common.”

“Work is over at this time of night,” said Sir Dugald, icily. “If I can be of service to you in any little difficulty with the authorities here, or with regard to the postal arrangements, I shall be happy to see you in the morning. My office hours begin at six.”

“Do you wish to name any special time, General?”

“By no means, Mr Hicks.” Sir Dugald fixed a blank uncomprehending gaze on the American’s face. “It is my duty to support the interests of the subjects of friendly powers wherever I can, and I hope you will attend to state your case at the time most convenient to yourself.”

“I guess you don’t understand me, General. I can fix my own affairs, thank you. What I want is to arrange a trade. You give me what I want, and I give you what you want, do you see? I should prefer to speak to you in private as to the exact terms.”

“Any proposal you have to make to me must be uttered in the presence of these gentlemen, if you please.”

Mr Hicks laughed uneasily.

“Well, your way of doing business licks Wall Street,” he said. “What I have to say is, you give me the information I may need as to the plans and intentions of your Government, and I will give you some pieces of news without which you will do nothing here.”

“You are an accredited agent of the United States Government?” asked Sir Dugald.

“Not at all, sir. I represent the ‘Empire City Crier.’”

“And I represent her Britannic Majesty. I regret that the ‘deal’ to which you have referred cannot come off.”

“Then your Mission will be a failure, General.”

“Pardon me, but that is no concern of yours.”

“Well, you are the first man I ever knew bring a wife and daughter into a place like this on such an almighty poor chance. I don’t know what you think, gentlemen”—Mr Hicks wheeled round in his chair and glanced at the rest of the party—“but I say—and I know something about this place—that you have a precious small hope of getting out of Kubbet-ul-Haj with your lives if your Mission does fail.”

“You really must excuse my staff from commenting on your interesting piece of information, Mr Hicks,” said Sir Dugald, smoothly; “but they are not accustomed to be set up as a court of appeal over me.”

“May I ask, General, whether you know why Fath-ud-Din, the Grand Vizier, did not ride out to welcome you to-day?”

“I believe he was ill,” said Sir Dugald, stifling a yawn.

“He was so sick that he was riding past my house to the bath at the moment you were entering the city on the other side.”

“I don’t quite see,” said Dick, “why a piece of bad manners on Fath-ud-Din’s part should be such a fearful omen for us.”

“I guess you think yourself dreadful smart, Colonel,” returned Mr Hicks; “but you soldier officers are a bit too cute sometimes. Old Fath-ud-Din is a bad crowd generally, and he means mischief. Leaving him out of account, what do you think has happened to your friend the Crown Prince, Rustam Khan? Has he dropped in on you here yet?”

“Scarcely,” said Dick. “We have not arrived so very long, you know.”

“That is so.” Mr Hicks disregarded the sarcasm implied in the words. “But I know something of that young man, and I can tell you he would have been around here like greased lightning if he had had the chance. He was afraid of losing his scalp if he attempted it. The fact is, you gentlemen are behind the times.”

“Ah, but we’ll be truly grateful if you’ll enlighten us a little,” put in Fitz, in a most alluring brogue, which he kept for use on special occasions.

Mr Hicks glanced sharply at Sir Dugald. The slightest sign of interest or eagerness would have determined him to impart no information except at a price, but the look of repressed weariness which was just visible in the half-light served to pique the American into doing his best to surprise and startle his bored and scornful host. He leant back in his chair with his thumbs stuck in his waistcoat pockets.

“We think we are pretty slick in fixing things out West,” he said, “but they have by no means a bad notion of history-making out here. When it was arranged that your Mission should start, General, Rustam Khan was in high favour with his father, old Fath-ud-Din was biting his nails in disgrace, and the people were all in love with the English. But we have had a Palace revolution since then. The King’s second wife (she is Fath-ud-Din’s sister, and they all hang together) gave her husband one of her slave-girls, the prettiest she could pick up anywhere, and that brought her into high favour, and all her relations with her. She is young Antar Khan’s mother, and he is prime favourite now, while Rustam Khan and his mother, the King’s first wife, are nowhere. Curious what little things bring about these big changes, isn’t it?”

“The details of these Palace scandals are scarcely edifying,” remarked Sir Dugald, to whom Mr Hicks had all along been addressing himself.

“Probably not, General; but they are often important, and there is an outside circumstance that complicates this one. From your point of view it was slightly unfortunate that an envoy should turn up a week or two ago with presents and offers of alliance from Scythia and Neustria. I guess those two States are hunting in couples. It’s not the first time they’ve done it, and they generally make a good thing out of it. Does this alter your way of looking at things at all, General?”

“Not at all,” returned Sir Dugald, placidly.

“Now come, General,” said Mr Hicks, leaning forward and extending a long forefinger to tap Sir Dugald on the knee, “you and I are both white men. We understand each other. I can put you up to circumventing this Scythian cuss if you will only show an accommodating spirit.”

“Really,” said Sir Dugald, “I am deeply obliged; but until her Majesty is pleased to appoint me a colleague I have an invincible objection to sharing my duties with any one. I cannot sufficiently admire your disinterested and public-spirited offer of co-operation, Mr Hicks, but this prejudice of mine—foolish and incomprehensible as it must no doubt appear to you—prevents my accepting it.”

“Think of your reputation, General,” urged Mr Hicks, sadly. “I give you my word I had sooner write the story of a successful mission than an unsuccessful one any day. We newspaper men have a way of finding out things which you diplomatic gentlemen never hear of, and I can help you through with your work and cover you with glory as well. You’ll take it?”

“No, thank you,” returned Sir Dugald. “It is all prejudice, of course, but somehow I had rather not.”

“There are just a few people left in the world who prefer honour to glory,” cried Georgia her eyes flashing.

“What an unkind remark, Miss Keeling!” said Sir Dugald. “You will really wound my feelings if you impute motives to me in that reckless way. Well, Mr Hicks, I hope we shall see more of you. Lady Haigh is always at home on Friday afternoons, and if you care to drop in to tiffin any day we shall be delighted to see you.”

Mr Hicks had not been intending to depart so early, but at this intimation he rose reluctantly and took his leave. North and Stratford escorted him to the door, and when they had returned to the terrace a sense of constraint seemed to fall upon those present. Sir Dugald’s impassive face told nothing, and his eyes were fixed on a distant point of light in the city. He was the only one of the party who recognised the full importance of the piece of news which had just been announced, but all perceived more or less distinctly that the enterprise on which they were bound had received a check. It was Georgia who broke the silence at last.

“Sir Dugald,” she said, boldly, “won’t you say something? We couldn’t help being here and hearing what that man said, and we should like to know what you really think, just to hear what we have to expect.”

“I have never pretended to be a prophet,” said Sir Dugald, looking round with a half-smile, “and I fear I am not much in the habit of stating publicly what I really think. Still, after what has happened to-night, I will say that our task is certainly very much complicated by what our American friend has told us, though I see no reason for wailing over it as impossible. Palace revolutions are tolerably frequent in these countries, and Rustam Khan may be in favour again to-morrow. Of course the news about the Scythian agent is bad, but we do not hear that any treaty has been concluded, and we are now on the spot. If the people are reasonably well affected towards us, or are even keeping an open mind, the advantages we can offer ought to convince them that it is to their interest to make friends of us. They appeared friendly enough this morning.”

“Hicks told us at the door,” said Dick, “that the King and his Amirs were very much divided in opinion, some of them advocating the alliance with us, some that with Scythia, and others that the old position of isolation should be maintained. The worst of them, he says, is an old fellow called the Amir Jahan Beg, who is Rustam Khan’s father-in-law. ‘He is the deadest-headed old reactionary I ever saw,’ Hicks said. ‘All the other fellows turn round in the street to look after me and show a little interest, but this old cuss rides right on and takes no notice. The other day I sent my servant to negotiate an interview, and all the answer I got was that the door was shut.’”

“Rather good, that, for Jahan Beg,” remarked Stratford.

“But if he is Rustam Khan’s father-in-law he may persuade him to take sides against us,” said Dr Headlam.

“We can do nothing until we see how the land lies,” said Sir Dugald. “To-morrow, when the King receives us for the first time, we shall get some idea of his attitude towards us, and we can take steps accordingly. There is only one thing that I must specially impress upon you, gentlemen: be careful when you are in company with Hicks. Even after his failure to-night I haven’t a doubt that we shall see a good deal of him. I invited him to come here now and then because I thought we should be acquainted with his movements occasionally, at any rate, and he accepted the invitation as likely to give him a means of finding out what we are doing. Of course he will bribe the servants here and at the Palace to bring him news; but he will certainly not neglect us. Therefore be careful what you say. I don’t want to misjudge the man, but he might not be above the temptation of taking steps to secure the fulfilment of his prophecy as to the failure of the Mission. In any case he might do a great deal of harm by sending home exaggerated or distorted reports of what had actually occurred. General conversation is the safest—no private talks. I would not answer even for you, Stratford, in the hands of a ‘Crier’ interviewer, although you are a past-master in the art of mystification. Even if you said nothing, that is not necessarily a barrier to his crediting you with a long oration. There is safety in numbers, for he could not derive much political capital from a conversation held in the presence of the whole Mission. Our policy is to show a united front.”

“If only that wretched man had never come to Kubbet-ul-Haj to spoil everything!” said Lady Haigh, somewhat ungratefully, it must be confessed, in view of the information imparted by Mr Hicks.

“Oh, don’t abuse him,” said Sir Dugald. “It is his business.”