CHAPTER VIII.

EAST MEETS WEST.

In spite of the very moderate encouragement he had received, hope must have told a flattering tale to the Vizier Fath-ud-Din when he left the Residency after his interview with Sir Dugald, for it became evident very soon that the hindrances which had threatened to obstruct the path of the Mission had suddenly been removed. Rustam Khan was restored to a measure of his father’s favour and allowed to appear at Court, besides being permitted to speak in the council on behalf of the English alliance, while the Neustro-Scythian agent found his promises received with unconcealed incredulity, and was tantalised with evasive answers to his demands. Of these changes the party at the Mission were kept informed both by Jahan Beg and by the Vizier himself, the latter losing no opportunity of insisting on the virulence with which his rival was opposing the English proposals, and the eagerness with which he advised the extortion of every possible concession. If it had not been for the explanation given behind the scenes by Jahan Beg himself, it would have been difficult for Sir Dugald to resist the conclusion, towards which Fath-ud-Din laboured continually to urge him, that the Amir’s hatred of his native country was deep-rooted and had a sinister origin; but the Vizier’s object was so apparent that it was fairly easy to distinguish the embroidery which he added to the speeches he professed to report. Jahan Beg’s opposition was all on points of detail, not of principle; and although he would haggle for hours over the rate of an import duty, or the terms on which an imaginary passport was to be granted, Sir Dugald forgave him the worry he caused in consideration of his services in bringing his colleagues and the King to look at matters from a business point of view. It was the Ethiopian idea that the King was the greatest monarch on earth, and that he could settle any trouble that might arise by the simple expedient of ordering the heads of the disturbers of the peace to be brought him, and it was difficult at first to wean the people, and especially the Amirs who formed the royal council, from this mediæval way of looking at things. In spite of Jahan Beg’s invaluable help in this respect, however, Sir Dugald did his best more than once to induce him to abandon his simulated policy of obstruction and support the Mission heartily, reminding him that he could not now deceive Fath-ud-Din, who knew him to be an Englishman. But Jahan Beg remained obdurate, declaring that if his proceedings did not blind Fath-ud-Din, at least they continued to deceive the rest of the Amirs, who would at once suspect him of having been bribed by the English should he appear to be suddenly converted to a warm interest in the treaty; while the Vizier himself, having already concealed for some time the fact which had come to his knowledge, was bound still to keep it secret, lest he should be punished for not revealing it before.

In consequence of Jahan Beg’s educational work, and Fath-ud-Din’s unexpected complaisance, Sir Dugald and the staff betook themselves day after day to the Palace, and were conducted at once to the King’s hall of audience. Here seats of rather an uncomfortable and nondescript character were arranged for them, for the camp-chairs they had brought with them were the only chairs in Kubbet-ul-Haj, or possibly in all Ethiopia, and a laboured conversation took place. When the King had satisfied a portion of his curiosity respecting men and things in England and Khemistan, Sir Dugald would contrive to lead the talk round to the more important matters in hand, and in this way the various clauses of the proposed treaty were discussed in turn, notes of the proceedings being taken in Ethiopian by the King’s scribe and the interpreter Kustendjian, and in English by Fitz Anstruther. When the Englishmen had taken their departure, the points touched upon would be discussed afresh by the King and the Amirs, and if no satisfactory conclusion had been reached, they reappeared the next morning with great regularity, while if all was well, the discussion moved on to a fresh stage.

In this way time passed not unpleasantly, varied with a certain amount of incident, so far as regarded Sir Dugald and his staff; but for the ladies it was at first very different. True, they had their own terrace, where they could go about unveiled, and their own courtyard in which to take exercise. When Georgia was in a cheerful frame of mind she called this court her quarter-deck; when she was feeling depressed she alluded to it as her prison-yard,—and here she paced along during the cooler hours of each day until Sir Dugald told her that her feet would wear a path in the stones. Sometimes, when public business prevented the King from receiving the Mission, its members would escort the ladies for a ride, but it was necessary to choose secluded tracks for these excursions, since public opinion in Kubbet-ul-Haj did not permit women to ride with men, unless simply for protection on a journey.

But when the Mission had spent about a month in the city, there came a change for Georgia. By way of propitiating Sir Dugald, who was beginning to wax exceedingly wrathful over the King’s ostentatious forgetfulness of the urgent request he had made for a lady doctor, Fath-ud-Din ventured to remind his august master of Miss Keeling’s existence, and her presence at his desire in Kubbet-ul-Haj. The King happened to be in a good temper at the moment, or perhaps his conscience had been pricking him for his neglect of Rustam Khan’s unfortunate mother, and the result of the reminder was the arrival at the Mission one morning of a covered litter carried by four men, and accompanied by an escort of cavalry, at the head of which rode a gorgeous negro, who brought the intimation that the doctor lady was requested to wait on the Queen.

That was only the first of many days on which Georgia ensconced herself in the litter with her maid Rahah, and with the curtains closely drawn was borne off to the Palace. A very short preliminary examination convinced her that the Queen was suffering from cataract in both eyes, and that an operation was absolutely necessary. But the matter did not appear by any means of so simple a character to the dwellers in the harem. Even when, with the aid of the Khemistani girl, Georgia had succeeded in getting things explained, in highly colloquial Ethiopian, to the Queen and her attendants, she found that they all shrank with horror from the idea of the operation. It was not merely that they distrusted herself, as an alien both in race and religion, but they were strongly of the opinion that whereas the use of any amount of medicine, the nastier the better, was lawful in cases of disease, the employment of the knife to give relief was a blasphemous interference with the designs of Providence. In vain Georgia told of the wonderful instances of recovery, following on operations such as she intended to perform, which had come within her own experience; it was Rahah who at last placed the question before the Queen in a way that appealed to her. Whatever happened was incontrovertibly due to the decrees of fate: if it was fated that the Queen should be blind, blind she would continue to be; but if the operation proved successful, it would be clear evidence that she was not fated to be blind. Influenced by Rahah’s logic, the Queen consented, with great reluctance, to allow the matter to be referred to her husband; and the next day Georgia, with Rahah as interpreter, held a colloquy on the subject with the King, through a grating which effectually precluded either party from gaining a glimpse of the other. The King was not so easily moved by Rahah’s eloquence as his wife had been, but eventually a compromise was agreed upon. It was evident to Georgia that, owing both to fright and to the sorrows of the past few months, the Queen was in no state for the operation to be performed at present. Some delay was therefore inevitable, and the King was at last brought to consent to the trial of the plan, if a week or two of careful diet and nursing, together with cheerful society and the blessing of hopefulness, should prove to have a beneficial effect on the patient’s general health.

It seemed to Georgia that, in view of the state of things in the Palace, each portion of the prescription was more unattainable than the rest; but after two or three days of vain endeavours to instruct the shiftless harem servants in the arts of nursing and of invalid cookery, and to restore tone to the mind of the poor Queen, weakened and saddened as it was by years of sorrow, she found a new ally at her side. Coming into the Queen’s room one day, she saw seated on the divan a tall girl with a fresh English face, blue-eyed and fair-haired, holding a closely-swathed baby in her arms. Although the stranger wore the Ethiopian dress, Georgia would have greeted her at once as a fellow-countrywoman, if she had not turned and stared at her with undisguised interest and pleasure, saying something in Ethiopian to the Queen. Then a great pang of pity seized Georgia’s heart, for she knew that the English girl before her must be Nur Jahan, Jahan Beg’s daughter and Rustam Khan’s wife.

Remembering her promise to Nur Jahan’s father, however, Georgia composed her face and took her usual seat beside her patient. The Queen was so much more cheerful this morning, that it was evident she enjoyed the presence of her daughter-in-law and grandson; and after a while, to Georgia’s delight, she brightened visibly at Nur Jahan’s suggestion that, when the operation had been successfully performed, she would be able to see the baby. When the medical examination was over, the young wife felt herself at liberty to talk, and Georgia learnt that, although she had now come for a few days to the Palace solely for the purpose of cheering her mother-in-law, she had not quitted it very long. When Rustam Khan fell into disfavour, he had put his wife and her week-old baby under his mother’s protection at once, fearing that neither his house nor that of Jahan Beg would be safe from the rabble of the city, who were warm partisans of Fath-ud-Din. With high glee, Nur Jahan narrated how her husband had come to visit her in secret, always at hours when the King was not likely to enter the harem, disguised sometimes as a woman and sometimes as a negro, in order to escape the Vizier’s spies; and how once he had actually met his father outside the Queen’s door, but stepping aside respectfully, had passed him without being recognised under the thick veil. To Georgia, the possibility of such adventures within the sacred walls of the harem was a new thing, and she enjoyed the gusto with which Nur Jahan related them. But the Queen thought differently, and began to moan feebly, as she pulled at the edge of the coverlet.

“Thou art always thus, Nur Jahan,” she said, querulously; “laughing and rejoicing when thy lord is in peril of his life. An Ethiopian woman, seeing her husband in such straits, would have shed an ocean of tears, and refused to be comforted until times had changed; but I have seen thee, when Rustam Khan had but just gone from thee, planning eagerly how he should enter the Palace on the next occasion, without letting fall a tear.”

“But it was that which pleased my lord, O my mother,” said Nur Jahan, eager to defend herself. “What delight had there been in our meetings, if I had only sat at his feet and bedewed them with tears? There was so much to tell, and so much to hear; how could I weep when my lord was with me? And when he was gone, was it not happier for me to consider how I might see him again, rather than weep because he could not be with me still?”

“Go thy ways, Nur Jahan,” said the elder woman, bitterly. “Thou too wilt one day learn that although the life of all women is sad, that of a woman who is also a king’s wife is saddest of all. How canst thou love thy lord as I, his mother, love him? Thine eyes are as bright as when he married thee, while mine are blind with weeping for him. But he loves the bright eyes better than the blind ones, and is it to be wondered at?” and the Queen rocked herself to and fro, and wailed hopelessly.

“O my mother, wilt thou break my heart?” sobbed Nur Jahan, throwing herself down beside her. “Can we not both love my lord? I know well that thy love for him has lasted longer, but must it needs be greater than mine? My lord’s love is my life, and yet thou wilt not believe it because I do not always weep when I am sad. O doctor lady, dost thou not believe that I love my lord?”

“What does the doctor lady know of it?” demanded the Queen. “But thou art my son’s beloved, Nur Jahan, and for that I love thee also. But I would thou wert as we are. Thou art of the idolaters through thy father, and thou dost not grow like us. But thy life is like ours, and, as years pass on, it will be more and more like mine, and if thou dost not weep then, what wilt thou do? Those who do not weep go mad.”

It was evident to Georgia that Nur Jahan was comforting herself with the thought that her husband was very unlike his father, while the Queen expected that in course of time he would exactly resemble him; but she saw that the excitement was bad for her patient, and interposed prosaically, with a suggestion as to the preparation of beef-tea, which Nur Jahan took up at once, displaying practical powers which encouraged Georgia to give her a first lesson in home nursing. But in spite of this cheering fact, Georgia’s heart still ached as she was carried back to the Mission in her litter, for she could not forget the contrast between the girlish form of Nur Jahan and the bowed and broken figure of the old Queen, who seemed so sure that her daughter-in-law’s life must one day come to resemble her own. But there was a trait in Nur Jahan’s character which had no part in that of the Queen, and which would go far to render her lot even harder—the adventurous spirit which her mother-in-law so bitterly resented, and which had caused her to find a certain enjoyment in the shifts and devices to which her husband had been obliged to have recourse in order to see her.

“Jahan Beg ought to have escaped from the country and brought her to England, as he thought of doing,” was Georgia’s mental comment. “It is his spirit she inherits, and it is cruel of him to rest satisfied with the life to which he has condemned her. She is ready to welcome any excitement, even of a disagreeable kind, as a relief to the monotony of her existence. I can see that she is pining for outside interests, though she doesn’t know it. In a man of English blood this would seem quite natural and proper to every one, and why should it be different for a woman? And what a life it is to which she has to look forward! Even if Rustam Khan keeps his promise and marries no other wife, she can only spend her days in doing nothing. Nothing to do for husband or children, in the house or outside, and to be surrounded by a number of other women as idle as herself! ‘Better fifty years of Europe than a cycle of Cathay.’ I had rather have my thirty-two years of life than the poor Queen’s fifty, queen and wife and mother though she is. Her only advantage in being Queen is that she must not do the little pieces of work which would have fallen to her in another position. As a wife she has to share her husband with an indefinite number of other women, and as a mother she sees her sons treated like Rustam Khan, and her daughters condemned to the same kind of life as herself. Perhaps Nur Jahan’s children may inherit enough of her character to enable them to break the spell; but I am afraid the change won’t come in her time. The East moves so slowly.”

Since Georgia’s thoughts had been so deeply stirred on this subject, it was not wonderful that she communicated her views to Dick when they happened to be talking on the terrace that evening. She felt it a necessity to share her reflections with some one, and to her surprise he received them with unwonted meekness.

“Kipling doesn’t agree with you,” was all he said in answer to her estimate of the probable happiness of the Eastern as compared with that of the Western woman.

“Kipling!” said Georgia, in high scorn.

“I thought you admired him?”

“So I do. I think he is an excellent authority on men—at least, the men seem to find it so—but what can he, or any man, know about women? At best they can only see results and guess at causes. They observe very carefully all that they can see, and give us the result of their observations in knowing little remarks, half cynical and half patronising, and think they have gauged a woman’s nature to its very depths. Then she does something that throws all their calculations wrong, and they say that she is shallow and fickle, and, above all, unwomanly; whereas it is only that either their observations or their deductions were incorrect.”

“Still,” said Dick, “I am inclined to agree with a very comforting doctrine I heard you enunciating to Stratford the other night. You were speaking of the principle of balance, and you said that when one side of the truth had been exclusively insisted upon for a time the pendulum swung back and the other side became prominent until it was the first one’s turn again. I thought it was a very good idea—for the people who can keep just in the middle. Those who rush to either extreme must find themselves rather left when the pendulum swings.”

“But what has that to do with our present subject?” asked Georgia.

“It seems to me to apply. You see, the New—I beg your pardon; I know you dislike the term—the modern female has had rather a long innings lately. You have often said that you don’t agree with all her developments, which seems pretty clear proof that she has at any rate approached the extreme point. Well, Kipling comes to show us the other side of the matter, exaggerated, perhaps; but that is unavoidable, owing to the exaggerations on the lady’s part. At least, that is how it strikes me.”

“North, where are you?” said Stratford, appearing suddenly on the terrace. “The Chief wants you for something.”

Dick rose and disappeared, with an apology to Georgia, who leaned back in her chair and smiled.

“He is improving wonderfully,” she said to herself. “Two months ago he would never have talked as he has to-night. Crushing assertions without any proof used to be his idea of arguments. He must have taken a lesson from Mr Stratford. Was he really listening all the time I was talking to him the other night? He has certainly changed very much, and I am very glad of it. It would have been most unpleasant if the only man who could not bring himself to be civil to me was such an old friend, and Mab’s brother.”

If Mabel could have heard this soliloquy, it is probable that she would have smiled darkly to herself, and remarked that her dear Georgie must have been considerably piqued by Dick’s cavalier behaviour for her to make such a point of having overcome his opposition to herself. However, there was no one at hand to point out to Georgia that she felt more satisfaction in one amicable conversation with her former lover than in all the attentions of Stratford and the doctor, who entertained no prejudice against medical women, and always appreciated the honour of a talk with her. It may be that it was merely the feeling that she had been victorious in disarming Dick’s hostility which gave such a zest to her intercourse with him; but if this was so, an incident which occurred a few days later ought to have cast some additional light upon the subject.

Matters had been going very smoothly at the Palace of late, and Sir Dugald had the satisfaction of knowing that all the clauses of the projected treaty had been in substance agreed to. It now only remained to draw it up in formal shape, and to ratify it by the signatures, or rather seals, of the contracting parties. While the draughtsmen on both sides were busy reducing the notes taken during Sir Dugald’s audiences of the King into suitably involved phraseology, the members of the Mission enjoyed a short holiday. They made several expeditions into the districts lying around the city, and one day the King invited the gentlemen of the party to visit a summer-palace which he had erected on a spur of the hills some fifteen miles away. Mr Hicks, who had remained doggedly at his post in spite of the rebuff he had received, and contrived to glean sufficient news from his talks with Fath-ud-Din and the gossip of the Mission servants to fill the requisite number of columns per week for his paper when supplemented by his own lively imagination, was to be of the party, and the younger men anticipated some amusement in baffling his insatiable curiosity. They rode off in high spirits, the outward expression of which was modified in deference to Sir Dugald, to whom the excursion appeared in a light which was anything but pleasurable; and Lady Haigh and Georgia resigned themselves to a long, slow, quiet day. It was not one of the days on which Georgia visited her patient at the Palace, and therefore Lady Haigh and she wrote up their diaries with great industry, compiled several lengthy descriptive letters for the benefit of friends at home, and filled in odd corners of time with reading and talking. As the afternoon wore on, Lady Haigh went to remind the cook to make a particular kind of cake, likely to be appreciated after a long, dusty ride, for tea, and Georgia was left alone on the terrace.

As she sat there reading, the noise of horses’ feet in the outer court came to her ears, and she dropped her book, wondering whether the party had already returned. Presently Fitz Anstruther made his appearance under the archway which furnished a means of communication between the two courtyards, and catching sight of Georgia on the terrace, hurried towards her, followed by Dr Headlam. Fitz had something in his hand, carefully wrapped up in leaves and tied with wisps of grass, and as he reached the top of the steps he deposited it at Georgia’s feet.

“There, Miss Keeling,” he cried, in high delight, “I’ve got a spotted viper for you, for the collection! He’s a really fine beast; that measly old specimen the doctor got hold of hasn’t a look-in compared with him. See him, now,” and he unrolled the wrappings and displayed, as he said, a remarkably good specimen of the deadliest snake known to Kubbet-ul-Haj. It was only about twenty-seven inches long, but the spots, from which the Mission had given it its hopelessly unscientific name, were unusually brilliant.

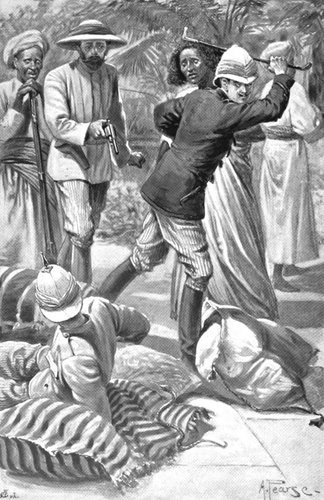

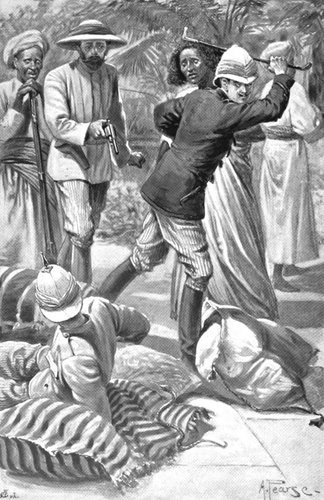

“You very nearly had the chance of labelling him as a murderer,” Fitz went on, holding up the snake’s head and examining its fangs with the air of a connoisseur. “He reared up suddenly, just behind North, and had his head stretched out to strike. North was leaning on his elbow on the cushions, and when he saw all the Ethiopians staring at him as pale as death, he turned round. There was no time to move away, and he cut at the thing with his knife and missed. We were eating fruit just then, all smothered in snow from the hills. Stratford had his revolver out in a moment, and was going to fire, but I yelled out to him to stop. I didn’t want the skin spoilt, and I knew that a shot at that distance would smash the head all to smithereens. I had my riding-crop handy, and I jumped up and managed to catch the beast such a whack that it broke his spine or something. Anyhow, he was killed, and I brought him home all the way on purpose for you, Miss Keeling.”

He reared up suddenly, just behind North, and had his head stretched out to strike.

Georgia had turned pale and stepped back a little as Fitz looked up for her approval. Seeing her hesitation, Dr Headlam interposed.

“It really was very neatly done, Miss Keeling, though it was a risky thing, both for Anstruther and North. When I saw the crop come down, I could hardly believe that in his ardour for science Anstruther had not sacrificed North. It was a frightfully near business.”

“Who cares about North?” Fitz wanted to know. “It’s a jolly good specimen, Miss Keeling, and your beast is better than the doctor’s, at any rate. Your collection will take the cake now, I know.”

“Must it be stuffed?” asked Georgia, with unwonted timidity. “I don’t like it. It—it frightens me.”

“Oh, Miss Keeling!” cried Fitz, deeply wounded. But Dr Headlam interposed again.

“I should be pleased to stuff it for you, Miss Keeling; but don’t you think that under the circumstances it would be better to take it home in spirit? It is a new species, so far as we know, and this is quite the finest specimen we have come across, so that some toxicologist might be glad to dissect it. I think we must preserve it in the interests of science.”

“Oh yes, of course, in the interests of science,” said Georgia, unsteadily. “It is really very foolish of me to object to it,” she went on, with a nervous little laugh. “I can stand most creatures, but snakes are such horrible things. It makes me feel quite queer.”

“I’m awfully sorry,” said Fitz, moved to compunction. “I never thought you mightn’t like it, Miss Keeling. I’ll tell my boy to throw the beast away at once.”

“Oh no, please don’t,” said Georgia, “if Dr Headlam is kind enough to preserve it. You will keep it over at your house with the rest of the things, won’t you, doctor? And you mustn’t think I am not pleased with it, Mr Anstruther. It was most kind and considerate of you to think of me at such an exciting moment, and I shall value the snake always as a memorial of your bravery and coolness,” and Georgia rushed away to her own room, where she threw herself upon the divan and broke into wild peals of laughter. That Fitz should think of saving the snake’s skin whole for her when Dick North’s life was at stake! It was too funny! Georgia laughed till she cried, and Lady Haigh came in and accused her of going into hysterics—an accusation which was vehemently denied—and administered cold water and particularly pungent smelling-salts.

But the snake was duly deposited in a huge bottle of spirit, and, in common with the rest of the collection, became a prominent object in Dr Headlam’s waiting-room. It inspired both awe and interest in the patients, especially after Fitz—who sometimes assisted the doctor in receiving his visitors—had delivered a lecture on the subject.

“I don’t know when I have laughed so much,” said Dr Headlam, telling the story after dinner that evening. “I happened to be a little late in going into the surgery this morning, but when I got near the door I became aware that Anstruther was improving the shining hour in the waiting-room. His discourse sounded so interesting that I lay low just outside and listened. It was delivered in English, helped out with all the Eastern words he knew, but it was so vividly illustrated by gestures that it seemed to have no difficulty in penetrating into the minds of all the patients. ‘These all devils,’ he informed them, pointing to the bottles of specimens; ‘big devils, little devils, all shut up safe. See this one?’ he took down the celebrated snake, which certainly does look rather vicious, coiled up in its bottle. ‘This snake-devil—ghoul—jinni—shaitan; you see? This one, eye-devil,’ pointing to that diseased eye which I removed for a man a fortnight ago, and took such pains to preserve, ‘finger-devil, tongue-devil,’ and so on. ‘Now, you like me to open one of these bottles?’ A delicious shiver of anticipation went through the audience as he took down the snake again. ‘You know what will happen if I throw it down? There will be a great crash, and you will smell the vilest smell you ever smelt in your lives, and you will see—what you will see, and the devil will be loose! Now, one, two, three and——’ but they were all on their knees begging and imploring him not to do it, and I judged it as well to make my appearance at that juncture.”

“You will have the town-boys raiding your diggings and destroying the bottles to see what happens when the devil does get loose,” said Stratford.

“I don’t think so,” returned the doctor. “They are all so frightened that it is as much as I can do now to get them into the same room with the collection. It is as good as a watch-dog to me.”

“Anstruther will have to be careful,” said Sir Dugald, with an approach to a frown. “We don’t want our characters blackened by any suspicion of dealings with infernal powers. I rather wish you had broken one of the bottles before them, doctor, to convince them that it was a joke.”

“Rather it would have convinced them that I was letting out a pestilence on the country,” said the doctor; “and they would simply have gone away and died of fright, which would be clear proof that I was their murderer. I think we are safer with the bottles unbroken.”

“I never like fooling about with supernatural nonsense in these countries,” said Sir Dugald. “It gives the people a handle, and they are not likely to be slow in taking it. As we four are alone together, I may give you a hint that I expect trouble before long. Things have been going too smoothly of late, and Kustendjian tells me that Hicks said to him yesterday, ‘Your old man has squared Fath-ud-Din nicely up to now; but what will he do when the bill comes in? He ought to know by this time that the man who calls for the drinks pays.’ I cannot flatter myself, unfortunately, that I have squared Fath-ud-Din; but if he considers that I have attempted to do it, it is quite on the cards that he will send in his bill. We can refuse payment, of course; but I am afraid that will not better our position very much.”

The justice of Sir Dugald’s words was recognised a little later, after another mysterious evening visit from Fath-ud-Din. The Vizier came to the Mission because he wished to know when his rival was to be permanently removed from his path. He had done all in his power to smooth the progress of the negotiations; but Sir Dugald had made no attempt to accuse Jahan Beg to the King or to demand his extradition. The answer was simple. Sir Dugald had declared his readiness to demand the surrender of Jahan Beg if it could be proved that he was in exile in consequence of any crime committed on British territory; but not a vestige of evidence that such was the case had been brought forward, and it was impossible to extradite him merely for the sake of pleasing the Grand Vizier. On hearing this, Fath-ud-Din flew into a transport of rage, and, from the words he let fall in his anger, Sir Dugald gathered that he had been expected to be prepared with a case against Jahan Beg, and false witnesses to support it, in return for the Vizier’s help. This was a little too much even for Sir Dugald’s self-control, and, in the few minutes that followed, Fath-ud-Din probably heard a larger number of home-truths, delivered in a cold, judicial voice that was more effective than any amount of shouting, than he had ever done before in his life. Baffled and disappointed, the Minister left the Mission, muttering curses between his teeth, and was observed by Kustendjian to pause outside and shake his fist at