CHAPTER XII.

THE STANDARD-BEARER FALLS.

Sir Dugald’s prophecy as to the probable resumption of negotiations on the part of the Ethiopians proved correct, for within a week after the doctor’s death Fath-ud-Din, now completely recovered from his illness, appeared once more at the Mission. As the visit was ostensibly one of condolence, Sir Dugald granted him an interview; but when the Vizier had spent the orthodox length of time in bemoaning the loss of Dr Headlam, and in remarking piously, for the consolation of his host, that these things were ordered by fate and could not be averted, he turned suddenly to business. Taking from the hands of his confidential scribe, who alone of all his attendants had accompanied him into the Durbar-hall, a roll of parchment which bore a family likeness to the various abortive treaties already discussed and rejected, he presented it to Sir Dugald and requested him to read it. Sir Dugald had now become so much accustomed to mental exercises of the kind that he could detect an unsound clause by eye or by instinct rather than by actual perception; but for the sake of appearances he beckoned to Kustendjian to come and read the document through to him quickly. When the reading was finished Kustendjian was pale with excitement, and Stratford and Dick were looking at one another in bewilderment over Sir Dugald’s head, for, with the exception of one or two minute alterations affecting the wording rather than the matter, the treaty was identical with that first agreed to, and ever since rejected by the King and Fath-ud-Din. That estimable person now sat smiling benevolently at the astonished faces of his hosts, and, while their eyes were still fixed upon him, began to make significant passes of the thumb of his right hand over the forefinger—a gesture which was immediately understood by all the members of the party except Fitz, for whom this journey was his first experience of Eastern life.

“So that’s it!” muttered Sir Dugald. “How much do you want, Fath-ud-Din?”

With a pained smile, directed towards the scribe, who was obviously watching the transaction while pretending to be absorbed in the study of the tiled floor, the Vizier held up his right hand, with the second finger turned down.

“Oh, nonsense!” said Sir Dugald. “You can’t afford to do it for that, you know. Or is there any other little thing we could do for you besides? Out with it; we are all friends here.”

“The life of man is uncertain,” sighed Fath-ud-Din.

“Quite so—especially in Ethiopia,” responded Sir Dugald.

“Even kings cannot rule for ever,” went on the Vizier.

“I quite agree with you;” yet Sir Dugald became portentously stern all at once.

“And happy is he to whom a son is given that may sit on his throne after him.”

“True. His Majesty is in that fortunate position.”

“But the son granted to him is young and tender, and there are those who might dispute his claim. How great, then, would be his felicity if the mighty Queen whom my lord serves would acknowledge, by the hand of her servant, the child’s right of succession, and grant him her countenance and the support of her soldiers!”

“I see. Fath-ud-Din stands to gain five thousand pounds, gentlemen,” said Sir Dugald, turning to his staff; “and when the king is removed from the scene, we are to acknowledge Antar Khan as his successor, and back him up with moral and physical force. How does that strike you?”

“It strikes me that the King had better set about making his will,” said Stratford, grimly, “if you accept the terms.”

“That is exactly the impression which the proposal has produced on me,” returned Sir Dugald; “and, as I have no wish to be accessory to a sudden change of ruler in Ethiopia, I think it will be as well to inform Fath-ud-Din that we must decline to do business with him on this footing.”

He folded up the treaty, rising at the same time to show that the interview was ended, and handed back the parchment to the Grand Vizier, who had been observing him in silence.

“Her Majesty’s Government has an objection to interfering in dynastic questions,” said Sir Dugald, pointedly; “and, when it does interest itself in such a matter, it prefers to adopt the cause of the elder son.”

“There are other governments of Europe,” said Fath-ud-Din, with equal meaning, “which are quite willing to take the side of the younger. If the first purchaser will not pay me the price I ask for my sheep, I will take them further and find one who will.”

“I can only admire your Excellency’s keen business qualities,” returned Sir Dugald, as he escorted his visitor to the door. But no sooner was the Vizier’s train outside the gate than the scribe came back in haste, saying that his master had missed a valuable ring, which he must have dropped somewhere in the house. Half suspecting a trap, but yet determined to give no ground for an accusation of lukewarmness, Sir Dugald had the courtyard searched, and the rugs in the Durbar-hall taken up and shaken. But all was in vain until one of the servants, who had removed the tray of coffee which had been brought in out of compliment to the Vizier, came back into the room, and, with a salaam, produced the ring, which he had found at the bottom of Sir Dugald’s cup, and which the scribe seized upon immediately with a cry of triumph.

“Well, I’m glad that turned out all right,” said Dick, when the man had gone off rejoicing. “I was afraid it was a trap, and that they meant to accuse us of stealing the thing. Dim memories began to come over me of a book I read when I was a small boy, in which a virtuous family were imprisoned and tortured and given a bad time generally on account of a false accusation of having stolen a ring, and I must own that I had unpleasant forebodings as to the probable course of justice in Ethiopia.”

“I confess that I began to suspect they had hidden it somewhere,” said Sir Dugald, “and would try to make out that we had accepted it as a bribe.”

“Of course it must have dropped in when he handed you the treaty,” said Stratford; “but it’s queer that no one noticed it.”

“One of the ‘things no feller can understand,’” quoted Sir Dugald, absently. “If you will find your way to the terrace, gentlemen, where I see Lady Haigh is just pouring out tea, I will follow you as soon as I have given an order to Ismail Bakhsh.”

Stratford, Dick, and Kustendjian crossed the court slowly, still discussing the incident of the ring, and, mounting the steps, perceived that Fitz had reached the terrace before them, and was engaged in conducting the education of the Persian kitten. He had an idea that it was possible, by dint of kindness and perseverance, to teach any animal to perform an unlimited number of tricks; but so far his theory did not appear to be justified by facts in the case of Colleen Bawn. At this moment he was holding a stick a few inches from the ground, and endeavouring, by means of bribes and encouragement, to induce his pupil to jump over it. Lady Haigh and Georgia were laughing at his efforts, and the kitten sat watching him with unconcerned interest, blinking lazily every now and then with one contemptuous blue eye and one uncomprehending yellow one.

“Now, you little beggar, this won’t do! I shall have to take you in hand seriously. I won’t hurt the little beast, Miss Keeling. You don’t imagine I would? But I must teach it to obey orders.”

He seized the white mass of fluff which ignored his blandishments so calmly, and proceeded to place it in the required position. The result was a short scuffle, from which the kitten retired in high dudgeon to seek refuge under Georgia’s chair, leaving Fitz defeated, with a long scratch on the back of his hand.

“Oh, Mr Anstruther, you have hurt her!” cried Georgia, reproachfully.

“I think she has hurt me,” was Fitz’s resentful answer.

“Poor little thing! I think she is only frightened,” said Lady Haigh. “We will give her some milk”—and she filled a saucer, and, stooping down, tried to tempt Colleen Bawn out of her hiding-place.

It was at this moment that the rest, standing at the edge of the terrace, saw Sir Dugald coming through the archway from Bachelors’ Buildings.

“What in the world is the matter with the Chief?” whispered Stratford, quickly; for Sir Dugald was walking as though his feet refused to carry him in a straight line: first a few steps to the right, then a valiant attempt to reach the steps, then a divergence to the left. The men on the terrace watched him in amazement and horror.

“He walks as though he was drunk!” said Kustendjian, in a voice of bewilderment.

“I wish to goodness he might be!” was the astonishing aspiration which broke from Dick as he ran down into the court, while Stratford turned a look upon the interpreter which made him shake in his shoes.

“Give me your arm up the steps, North,” said Sir Dugald, looking at Dick in a puzzled, almost appealing fashion. “I don’t feel very well. Is Anstruther there?”

“Yes, sir. Do you want him to write anything?”

“Yes. It must be done at once.”

They had reached the top of the steps, and the horrified group on the terrace saw that Sir Dugald’s face was working strangely, and that his lips were twitching and refused to be controlled.

“Dugald,” cried his wife, rushing to him, “you are ill! Come indoors and lie down;” but he pushed her away from him with a shaking hand.

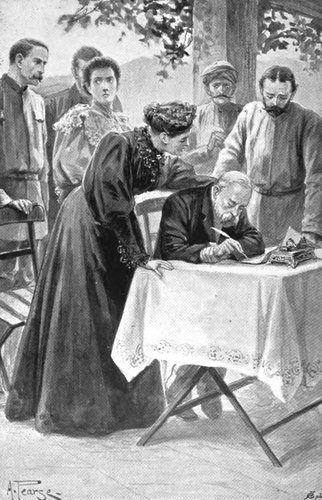

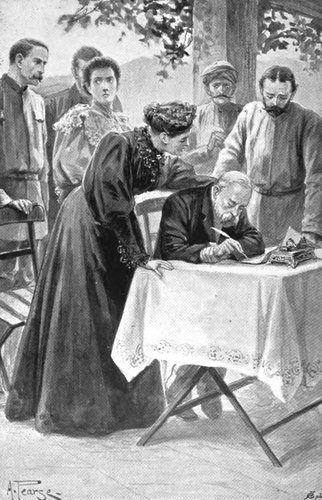

“Not yet, not yet,” he said, impatiently. “Sit down, Anstruther, and write. Quick!” as the boy’s frightened fingers bungled over their task. “Say this: ‘Fearing the approach of severe illness, I hereby appoint Egerton Stratford to the command of this Mission until her Majesty’s pleasure is known, charging him——’” here he became incapable of speech for a moment, and passed his hand over his lips to steady them—“‘to secure, if possible, the conclusion of the treaty originally agreed upon; but in any case to conduct the Mission back to British territory without provoking, for any cause whatever, a conflict with the Ethiopian authorities.’ Now let me sign it.”

He sat down heavily in the chair which Fitz vacated, and groaned aloud as the pen dropped from his fingers.

“Let me guide your hand, dearest,” whispered Lady Haigh, restoring him the pen; but once more he motioned her aside, and, steadying his right hand with his left, succeeded, with infinite difficulty, in inscribing his name in large crooked characters.

He succeeded, with infinite difficulty, in inscribing his name in large crooked characters.

“Now witness it. Witness it all of you,” he said, with feverish anxiety, and they all added their names to the paper as witnesses. When the last signature was written Sir Dugald’s head sank on his breast, and Lady Haigh darted to his side with a cry which none of those who heard it will ever forget.

“Dugald, not dead? and without a word to me!”

“Dear Lady Haigh,” said Georgia, gaining her voice first, and choking back her tears, “he is not dead. I think it is some kind of paralytic seizure. He may recover very soon. If we can get him indoors I shall be able to see better what it is.”

“If you will take his left arm, Mr Stratford,” said Lady Haigh, in a hard, even voice, “we can support him to his room. Please come with us, Georgie.”

Dick stepped forward to offer his help, but Lady Haigh refused to relinquish her position, and she and Stratford half-carried the unconscious form across the terrace and into the house. It struck those who were left behind with a fresh pang as they realised that in the course of the past few weeks Sir Dugald’s iron-grey hair had turned quite white.

“What do you think?” asked Dick, when Stratford returned presently and sat down in silence.

“Heaven help us!” was the sole answer; and the group on the terrace waited there in speechless anxiety for more than an hour. The sun, as it neared its setting, began to cast the long shadows of the walls across the courtyard; the kitten curled itself into a ball of white fur in the middle of Georgia’s embroidery without rebuke, and still the four men waited, struck dumb by this sudden blow. At last Georgia came out and sat down in Lady Haigh’s place. There were traces of tears on her face, but she spoke in what Dick called her professional manner as they all looked at her, hesitating to ask the question whose answer they feared to hear.

“It is paralysis,” she said; “but I have never seen a case with quite the same symptoms.”

“All this worry has been too much for the Chief,” said Stratford, indignantly. “The Government had no business to send so old a man on such an errand so ill-supported. What with all he has gone through, and the shock of the doctor’s death, it is no wonder that he should break down.”

“I don’t know who started the idea of this precious Mission,” growled Dick, “but if any of us get back to Khemistan, we shall have something to say about the way they carried it out.”

“I think that perhaps poor Sir Dugald preferred to come with a small party, and to be left very much to his own responsibility,” suggested Georgia. “He has often said how much he hated being trammelled by directions from people at a distance who knew nothing of the circumstances.”

“Still, they should have arranged some safe means by which he might communicate with them in case of necessity, instead of camel-posts which stopped running just when they were most wanted,” persisted Dick. “The responsibility has been too much for any one man.”

“I have an idea,” said Georgia, with some hesitation, “that the case is not quite so simple as you think. I have attended a large number of paralytic cases, but I have never met with symptoms quite like these. Sir Dugald has now passed into a state more resembling coma—that is to say, he is apparently asleep, but cannot be awakened. He seems incapable of originating any movement, and yet I am almost convinced that he is partially conscious of what is going on around him. He cannot speak or open his eyes; but his limbs are not rigid, and I believe he is alive to sensations of physical pain.”

“But to what conclusions do these observations lead you, Miss Keeling?” asked Stratford.

“It is merely a conjecture of mine, but I think I have one or two other facts to support it. I believe that this attack is the result of the administration of poison.”

“Poison!” broke from her hearers in various tones of incredulity; and Stratford added, “With all deference to you, Miss Keeling, I can’t help thinking that you are generalising too hastily from the circumstances of poor Headlam’s death. What opportunity has there been for poisoning the Chief that would not have affected all of us equally?”

“Chanda Lal said something to Lady Haigh about a ring.”

“Fath-ud-Din’s ring!” The men looked at one another for a moment, then Stratford spoke again.

“But we are not in the days of the Borgias now. How could these people have become acquainted with such a trick as that?”

“Surely,” said Georgia, “it is more likely that the Borgias owed their methods to the East than that the East borrowed from them? We have learnt already, by sad experience, that Fath-ud-Din is a most expert poisoner, and we can guess that he would consider it to be to his interest to rid himself of Sir Dugald.”

“The thing is absolutely impossible,” said Dick, not considering the rudeness of his language. Georgia looked at him in some surprise.

“I may tell you that it was from examination of the symptoms that I first formed my theory, Major North, and that it was only when I was trying to find out whether there had been any opportunity of administering poison that I heard of the ring from Chanda Lal.”

“But are you acquainted with any poison which would produce exactly these effects?” asked Stratford. The rest waited eagerly for the reply, and their faces fell when Georgia answered—

“No, I am not. There are circumstances connected with the illness which I cannot explain by attributing it to the action of any specific poison of which I have ever heard. But you must have noticed in the papers about ten years ago various references to certain Asiatic poisons, the nature of which was quite unknown to Western medical men. It was supposed that a poison of this kind had been administered to a particular ruler whom it was desired to dethrone, and that it acted in such a way as to paralyse his will and his powers of mind. I do not say that this is the same poison—in fact I believe it can’t be, for that was supposed not to affect the physical powers in any way—but I think that this belongs to the same class. You saw how poor Sir Dugald struggled against the effects; only a man of indomitable will could have held out as he did. But he could not continue to resist, and when he had attained his great object, and signed that paper, his will-power collapsed suddenly. It is just possible that if the emergency had continued to exist, he might have held out, and succeeded in throwing off the effects of the poison.”

“And you really think it possible that enough poison to produce such results as these could be contained in that ring?” asked Stratford.

“I do; and I want you to help me to persuade Lady Haigh to allow me to try the effect of different antidotes. She is so thoroughly convinced that the attack is a simple paralytic seizure, brought on by overwork and worry, that she refuses to let me make trial of any strong remedies lest they should retard Sir Dugald’s recovery. But I am very much afraid that unless we can expel the poison from the system, or at any rate neutralise it, he will not recover at all.”

“I wish we had a proper surgeon here!” said Dick, rising and walking restlessly up and down.

“We have,” cried Fitz, bristling up at once in defence of Georgia.

“I meant a medical man,” said Dick, casting a stony glance at him.

“It seems to me, North,” put in Stratford, “that you forget we ought to be very thankful to have a doctor here at all. You can’t mean to imply that it makes any difference that—that——”

“That I have the misfortune to be a woman, as Major North thinks,” said Georgia, quietly.

“Well, I know that I would never let a lady doctor touch me if I was ill,” said Dick, with painful candour.

“I don’t think there are many that would care to,” snapped Fitz, who was boiling over with rage.

“Anstruther, you forget yourself,” said Stratford. “Miss Keeling, I must ask you to forgive us. We have been so much upset by what has happened that we really can’t look at things coolly. We know that North has always been an obstinate heretic on this subject, but I’m sure I need not tell you that if he was really ill he would be only too grateful if you would do what you could for him. Still, in the present case——”

“Yes?” said Georgia, eagerly, as he paused.

“It is such a fearful risk. If you could say definitely what poison you suspected, or even if we had any independent proof that poison had been administered at all, I would add my voice to yours in trying to persuade Lady Haigh to adopt your views; but as it is, you must confess that they are built up of a succession of hypotheses, and if the hypotheses are false, your treatment might do irremediable harm by weakening the patient to such an extent that he would have no power to rally from what may, after all, be what you called just now a simple paralytic seizure. You are quite convinced of the truth of your theory, I suppose?”

“I would stake my professional reputation upon it,” said Georgia; “but I suppose”—throwing back her head proudly—“that it would be quite useless to try to convince any one here that my reputation is as much to me as a professional man’s is to him. But it is not that—it is to see poor Sir Dugald lying there insensible, and Lady Haigh so miserable about him, and not to be allowed to try what I believe would set him right. After all”—her tone changed—“I am the doctor here, and I am not answerable to any one in authority. Why should I not try the remedies which commend themselves to me?”

“Scarcely without the consent of the patient’s friends——” began Stratford, puzzled by this new development; but Dick interposed roughly enough.

“No, Miss Keeling. If your hypothesis proved to be incorrect, and the result turned out badly, it might become a manslaughter case. It is quite out of the question that you should be allowed either to run such a risk yourself, or to expose the Chief to it, and I shall back Stratford up in preventing you from attempting anything of the kind you propose.”

“By force, I presume?” asked Georgia, sarcastically. “You seem to be losing sight of the fact that, if my theory is correct, it would be incurring the same guilt not to take the steps I recommend, Major North.”

“Allow me to say, Miss Keeling, that there are very few juries that would not prefer the opinion of four men to that of one lady.”

“I can quite believe it,” returned Georgia, scornfully, “after what I have heard to-day. It would make no difference that the woman was an M.D. of London, and that none of the men knew enough of medicine to describe the symptoms of arsenical poisoning. They must know best. Oh, I might have known that when Lady Haigh refused to listen to me there was no hope of getting four men to look at things in a less biassed way. She turned against me because anxiety for her husband has blinded her judgment for the time, but your opposition springs from mere prejudice. Thank you for the things you have been saying, Major North. One conversation of this kind teaches one more than months of ordinary conventional intercourse. If I were not so angry, I could laugh to think that we are wrangling here while poor Sir Dugald is lying in this helpless state—and that you should all combine to prevent my doing what I can for him, simply because I happen to be a woman!”

“I think you are a little unjust, Miss Keeling,” said Stratford. “My objection is not that you are a woman, but that you confess you cannot be certain of the facts of the case.”

“How could any one be certain under the present circumstances, unless Fath-ud-Din had confessed openly what he had done, and contributed a specimen of the poison for analysis? You know that if Dr Headlam had been alive you would not have thought of questioning what he saw fit to do. I only ask for fair play. Chivalry I don’t expect—perhaps it is as well that I don’t under the circumstances—but I have a right to ask for the justice that would be shown to a man in my position.”

And Georgia gathered up her work and the kitten, and retired very deliberately, with the honours of war, leaving the men disinclined for further conversation. Kustendjian betook himself to his own quarters, where he was in the habit of donning a semi-oriental costume in which to take his ease after work was done; and Stratford, accompanied by Fitz, who had listened with a certain mournful pride to Georgia’s indictment of North, adjourned to the office, there to compile the regular account of the proceedings of the day. When the record was complete, and Fitz had returned to the terrace, Stratford, who had lingered to arrange the papers in the safe, was surprised by the entrance of Dick, who lounged in moodily without saying anything, and propped himself against the wall.

“Why don’t you tell me that I am a dismal fool and a howling cad?” he inquired at last.

“If you know it already, though it’s rather late in the day now, it can’t be much good my repeating the information,” said Stratford, drily.

“Oh, go on! Swear at me, call me names—anything you like! I am positively yearning for a thorough good slanging—might make me feel a little better.”

“Then I should recommend you to apply to Miss Keeling. I don’t fancy you’ll want to repeat the experience.”

“Stratford, tell me what I am to do. I can’t think what possessed me just now. Of course, it stands to reason that we couldn’t allow her to do what she wanted. If she tried her experiments, and the Chief died, she would probably let herself in for an inquiry when we got back to Khemistan. Her name would be bandied about all over the place, and every wretched native penny-a-liner in India would be cooking up articles to reflect on medical women.”

“And, by way of improving matters, you gave her a taste of the sort of thing beforehand. It doesn’t seem to have occurred to you that Miss Keeling would probably care comparatively little for having her name bandied about in the papers if she was convinced that her friends—and I suppose you would call yourself one—believed in her.”

Dick stared. “But that’s all rot, you know!” he said. “If a woman won’t look after herself in those ways, one must do it for her. To think of her becoming the subject of bazaar gup!—why, you know, one couldn’t allow it. No, I’m not a bit sorry that I took her in hand and quenched her aspirations; but I am perfectly sick when I think of the way I did it. If she hadn’t taken it for granted that she was in the right all the time, I shouldn’t have got so mad; but it makes a man look such a cub to—to lose his temper when he’s arguing with a lady. As she said, I have done myself more harm with her to-day than months would undo. How can I put it right?”

“I haven’t a notion,” responded Stratford, cheerfully. “Any one would have thought from your manner that you were bidding successfully for a final rupture. Of course, the only possible thing to do is to apologise. As a gentleman, you can’t avoid that, but I doubt whether it will do you much good. If you will excuse my saying it, North, I think you have tried this Revolt-of-Man business once too often.”

“Rub it in!” said Dick, mournfully. “The harder the better.”

“Oh, get out!” cried Stratford. “This office isn’t a confessional. Eat your humble pie as soon as you get the chance, and be jolly thankful if your penitence is accepted. That’s all I have to say. Now clear out. Why, I have more hope of young Anstruther than of you. The way that cub has been licked into shape is wonderful. Three months ago he would have been at your throat for half the things you said to-day. Slope!”

Dick departed, but he found no opportunity of following the counsel of his too candid friend. The men dined alone that night, and neither Lady Haigh nor Georgia appeared on the terrace afterwards. The next morning, as there was no change in Sir Dugald’s condition, Lady Haigh ventured, at Georgia’s earnest request, to leave him to the care of Chanda Lal while she presided as usual at the late breakfast. Dick took the place next to her, which he had occupied of late, and secured for himself the first cup of coffee, as he invariably did.

“Major North,” said Georgia, shortly, “will you kindly pass me my coffee?”

Taken by surprise, Dick did as she asked, and her eyes met his in a defiant glance as she raised the cup to her lips. He read her meaning at once. She would have none of his protection; she preferred, indeed, to run the risk of being poisoned rather than owe immunity from such a fate to him. The realisation of this fact cut him more deeply than anything she had said the day before, and he began to regret the temerity with which he had plunged into the fray, although in talking to Stratford he had scouted the idea of entertaining such a feeling.

About an hour later, when Georgia, after careful reconnoitring to make sure that the coast was clear, had settled herself in a shady corner of the terrace to study in peace a work on poisons which she had found among Dr Headlam’s books, she was surprised by the sudden appearance of the man whom she least desired to see. He had evidently been engaged in inspecting the stores in the cellars under the terrace, for the first intimation she had of his vicinity was the sight of him as he came up the steps.

“I want to ask you to forgive me for what I said yesterday, Miss Keeling,” he said, standing before her.

“Can you forgive yourself?” asked Georgia, quickly.

“Not for the way in which I spoke—nor indeed for the things I said, but I think you would look more leniently on them if you realised that it was anxiety for you that prompted them.”

“Thank you,” said Georgia, raising her eyebrows, “but I am afraid that my poor feminine mind is scarcely capable of appreciating an anxiety which displays itself in such a marked—I might almost say such an unpleasant way. Perhaps you will kindly understand, after this, that I had rather be without it.”

It was undignified, she knew, but she could not resist the temptation to repay him in his own coin. Last night she had been angry and indignant when she realised how much his words had hurt her, and it gave her now a kind of vengeful pleasure to feel that she was hurting him.

“You are very cruel,” he said, “but perhaps I deserve it.”

“Perhaps?” Georgia sat upright, and her eyes flashed. “Major North, you conceived a prejudice against me the first time you saw me in the spring, and you spared no pains to make it evident. Thinking that you might possibly imagine yourself to have a just cause of complaint against me, on account of what happened long ago, although I should have thought it wiser and more dignified for both of us to forget the circumstance, I have done my best, for Mab’s sake, to treat you as I should wish to be able to treat her brother. I had begun to hope that you also had recognised the advantage of continuing our acquaintance on this footing, and I have been in the habit lately of speaking to you more freely than I should have cared to do to a declared enemy. In return, you do your utmost to humiliate me in the presence of Mr Kustendjian and Mr Anstruther. You have taught me a lesson; I confess that I have taken some time in learning it, but I shall not make mistakes in future.”

“Then you won’t even let us be friends?”

“I think it will be better not, Major North. The honour of your friendship is rather a trying one for the recipient; a stranger might even mi