CHAPTER XI

WHAT HAPPENED ON HUMPHREY’S PEAK

Jack’s party drove to Humphrey’s Peak as had been planned, and there they found that the automobile road leading part way up the mountain was in splendid condition. Therefore they decided to try to reach the peak, and get the marvelous view from the summit.

All went well while the good road continued, but once they got to the place where it became necessary to leave the car and take to horses, it was not quite comfortable. The guide thought they were taking chances against the weather—it had been cloudy all morning and the weather bureau had prophesied flurries of snow during the day.

“A little snow won’t melt us hardened tourists!” exclaimed Eleanor, laughingly.

“Not after one has lived through Flat Top blizzards,” added Polly, springing into the saddle on the horse she was to ride.

“That’s all right, miss, but October is the latest month the guides think safe for folks to try for the peak. If you-all insist upon going up, I can take you, but it must be at your own risk, remember,” explained the man.

“The weather has been unusually warm and open,” said Jack, coaxingly, “and we are sure there is no risk to take.”

“The guide ought to know his territory better than we do, Jack,” argued Mrs. Courtney, troubled at what would be best to do.

“Oh, come on, folks!” commanded Dodo, impatiently.

“Yes, do come on, or the day will pass in arguing,” abetted Jack, jumping into the saddle.

“Well, if you-all will promise me not to go beyond the zone which I think safe and will agree to turn and come back the moment I signify the return, I’ll take you,” finally agreed the guide.

“Don’t you do it, if there is any unusual risk,” begged Mrs. Courtney, anxiously.

“No, I won’t! If the young people will promise me that, it will be perfectly safe,” returned the man.

Being so eager to start for the climb, the four younger members of the group promised instantly. And off they started.

The altitude of Humphrey’s Peak is 12,750 feet, and the approach to the summit is made over a gradually ascending road and trail made through mighty forests of pine. Aspens grow in thick profusion here and there—so thick, indeed, that one could not thread a way between the trunks without chopping away the obstruction. Reaching timber line, however, nothing grows beyond to hide the bare crags which continue on up to the very summit.

On the ride through the magnificent forest the guide told of the extensive view to be had from the peak—directly north, fifty miles away, one could see the walls of the Grand Canyon; still farther, were the Buckskin Mountains of the Kaibab Plateau; to the north-east one might see the Painted Desert, and beyond that the Navajo Mountain. Then, turning southward, one could see the White Mountains; and, gazing westward, one saw the Mogollon Plateau and other famous ranges. The Santa Fé railroad threaded the valley east and west like a winding serpent with head and tail hidden from sight. Small towns and settlements dotted the country, and gave the necessary action to the wonderful picture.

“But I doubt if you will see these sights to-day, friends,” concluded the guide. “If you reach timberline without freezing in the saddle, you will do well.”

“I’m sure you do not appreciate our hardihood,” declared Polly impatiently. “I was brought up in the Rocky Mountains, near the highest peaks, and I am accustomed to this life.”

“You forget, Polly, that several years in New York City, in steam-heated houses, and the enervating life we live there, may have changed your hardihood,” remarked Mrs. Courtney, gently.

“Oh, well! that remains to be seen,” retorted Polly.

Nothing more was said about the hazards to be met on the way, and thereafter every one felt buoyant and happy, because of the delight in riding good horses and the exhilarating air of the mountains.

Up and up and up climbed the well-trained horses, and finally the guide called a halt to rest the beasts. The riders leaped from the saddles and stretched their legs and arms for a time, then walked around to investigate the plateau. Only a few minutes were allowed for the rest, then the guide called them to re-mount. As they ran to obey, Jack thought he saw a snowflake whirl across his vision. But he would not report it.

By the time all were ready to resume the ride, Jack was sure he saw another flake of snow falling slowly upon the horn of his saddle, still he would not speak of it.

But the guide had noticed the few scattered bits of snow, and he was determined to take no chances with his party. He led the way to a crosstrail on the mountain-side, and took the side trail instead of the one which ascended directly ahead of the riders. He planned to follow this gradually ascending road for a time, and, should the flurry of snow prove nothing more, he could regain the main trail farther on where another crosstrail struck upward. In case the snow came down heavier, and threatened to continue, he could lead his party back down the mountain from that crosstrail.

But a careful guide’s plans may go astray, even like the wise mice in the fable, and so it happened with Job Barnes.

The pines were noticeably shorter and more slender as the trail ascended higher and higher, and it was also seen that the trees looked tougher and many of them bore scars left by the winter storms. Many were twisted and their tops blunted from the fierce gales and blizzards which swept like cyclones over the peaks. But the trail continued good and interesting, and the little cavalcade rode on with many a merry jest and carefree laugh.

Finally they entered a thick forest of aspens through which the trail accommodated no more than one horse at a time. It was after riding halfway through the length of this forest, that a sudden gale of wind came down from the peaks, and with it came a great cloud of snow. Instantly the air became choked with fine snow, and the temperature dropped suddenly so that every one in the party began to shiver and shake. The horses, rebelling against going on in the face of this cold blizzard, balked, but they could not turn in the narrow tunnel between the aspens.

Fortunately the guide rode first, and Jack brought up the rear, so that the horses of the girls could not back nor forge ahead in order to get away from where they were.

“What shall we do?” shouted Jack, to get orders from the guide.

“Wait for a few moments and see if she blows over.”

So they all sat as though frozen to the saddles, while the guide tied a rope to the horn of his saddle and then jumped from his horse and carried the rope back to tie a loop to each saddle in the line behind his horse. When Jack’s horse, the last one, had been thus hitched up in line, the guide advised him.

“Don’t let your horse balk or stampede. Use your spurs, if necessary, to control him. We’re near a nasty bit of road that runs along the rim of a rocky ravine, and I’d like to keep this side of it if I can manage the animals so they will move slowly. I might have to chop down enough aspens to allow the horses to turn, so we can ride back the way we came, but chopping trees takes time, and I brought but one axe.”

“Oh, we’ll be all right,” was Jack’s assurance. “Just go on carefully, and warn us when we reach the gulch.”

Another ten minutes was given to a slow progress along the narrow trail, and, then, the storm growing heavier, the guide decided to dismount and begin to cut down enough aspens to permit a turn in the trail. As he jumped down, however, his feet became entangled in some way in the rope which he had tied to his saddle, and he fell. His foot struck upon a slippery projection of rock, and, turning over, down he crashed with a groan, bringing his heavy weight upon the twisted member.

The full import of this accident did not filter into the brains of the other riders for a second; then Jack saw the guide slump in a heap and he knew the man had fainted in spite of his endeavors to remain conscious.

“Great Scott! Barnes is knocked out! He must have hurt himself seriously!” cried Jack, springing from his saddle.

Polly was so experienced in handling situations of this nature that she quickly got down from her horse and hurried to the side of the injured guide. Before Jack could lift Barnes’ head, Polly was beside him and had placed a restraining hand upon his arm.

“Just make him as comfortable upon the ground as possible, Jack, and then help me straighten out his leg. Perhaps it is not badly hurt,” advised she.

Thus, while the other three riders waited anxiously, watching from their horses, Jack and Polly helped the guide to a more natural position, and Jack fumbled for a possible flask of whiskey in the man’s pockets.

Polly began to unlace the leather legging and heavy mountaineer’s boot, but her fingers were so stiff with cold that she could not undo the wet laces. Jack had found a flask, and, pouring the cup-top on the bottle full of brandy, tried to force some between the lips of the man.

Not more than five minutes had passed since the guide had first leaped from his saddle, but in that time the snow had fallen so heavily that everything was covered with a white blanket. And the gale increased in velocity so that it blew the snow in every direction, and seemed to drive it under the riding clothes of the stylishly clad tourists.

After a second attempt to get some brandy down the throat of the guide, Jack succeeded and was repaid by seeing the eyelids twitch and slowly lift. Then the man became conscious all at once, and sat up, though he did not move his foot—it seemed limp.

“What a fix!” exclaimed Barnes, in disgust with himself. “A broken bone, and out here in this blizzard!”

“That’s all right, Barnes—I’ll cut down the aspens for you, and Polly, with the other girls, will drag them out of the way. The work will keep us from freezing,” said Jack, cheerily.

“Don’t forget me,” called Mrs. Courtney, trying to act as cheery as Jack.

“If you only knew how to manage it, you ought to throw the blankets over the animals, or we may not have them fit to carry us back to the cabins,” suggested the guide.

“We do know how to do it,” replied Dodo. “I was brought up in Colorado, and Polly knows enough about horses to break the worst broncho. Jack, too, has been on the ranch. Just watch us.”

So saying, Dodo jumped from her saddle, and Eleanor managed to slide out of hers. It took Mrs. Courtney longer to dismount, as she had become so cold and stiff.

The three,—Jack, Polly and Dodo,—then began to remove the saddles that they might pull off the blankets which were strapped under them. This done, they started to rearrange the blankets in order to cover the quaking horses.

“Jack, you better get busy chopping the aspens, because Dodo and I can blanket the animals,” suggested Polly.

“Good! Hand me the axe from Barnes’ side,” returned Jack, turning to the man who was trying to get upon one foot and assist the girls.

“You just sit still, Barnes—or you’ll have a compound fracture. We’ll get this straightened out in a jiffy,” said Jack. Then he took the axe and began to whack at the nearest aspen. It was one directly ahead of Barnes’ horse, and Jack figured logically that cutting down the few ahead of the horses would make it easier for them to turn, because the leader could step in and go around the narrow turn he proposed making. Then they would face the opposite direction from the one in which they now stood.

Polly and Dodo had blanketed three horses, and all three girls were engaged with the others, when Jack whacked a hard blow at the tree he was felling. The axe struck sideways, and a long sharp chip flew up and scuttled horizontally through the air. It struck the leading horse directly between the eyes, and that poor beast, already frightened by the blasts of howling wind which bore such cold sheets of sleet and snow into his face and chest, leaped up on his hind legs. In a second, he came pounding down again, and then started off along the trail, pulling the other horses in his wake.

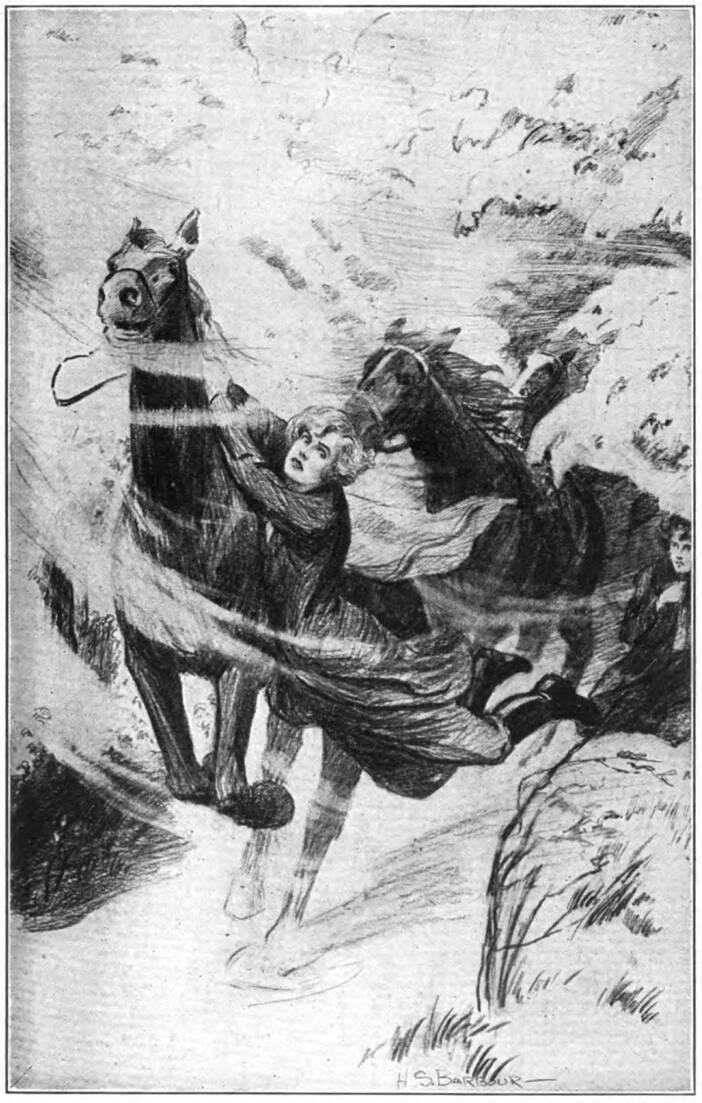

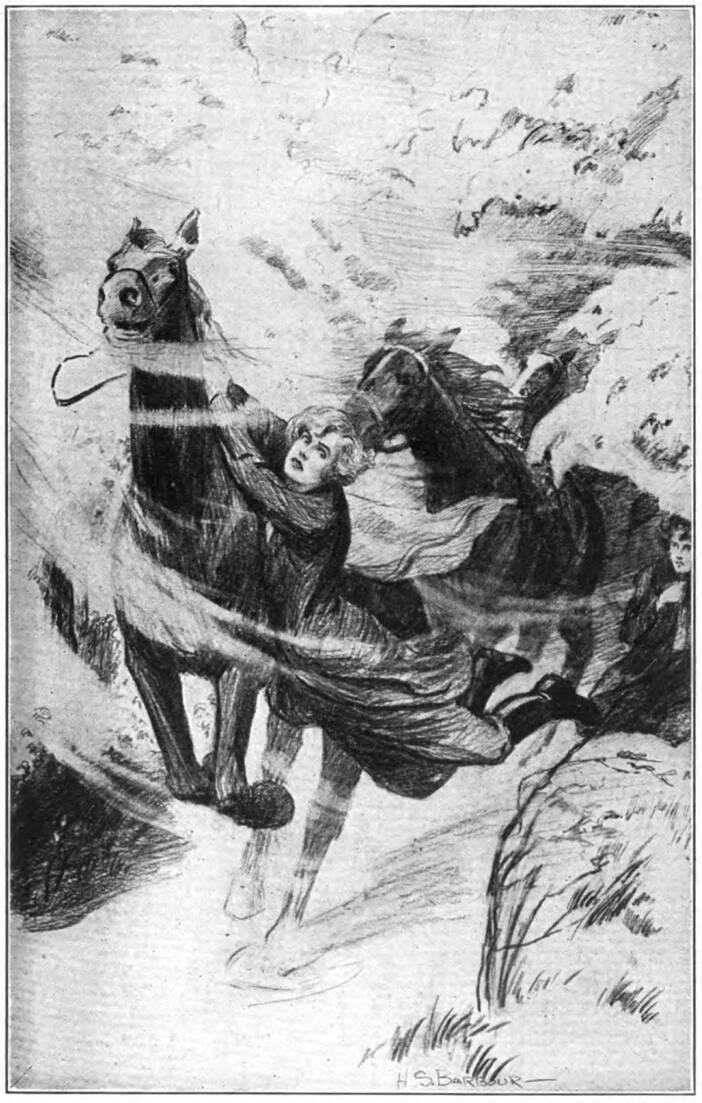

The three girls were so frightened at what had happened that they were incapable of moving for a moment; consequently Eleanor was thrown against an aspen with such force that she had the breath knocked out of her. Polly had been half over the back of one horse, in order to work a blanket down to the other side, and she was carried along while clinging desperately to the mane of the beast she was upon. Dodo was flat in a snow-drift.

POLLY WAS CARRIED ALONG CLINGING DESPERATELY TO THE HORSE’S MANE.

Mrs. Courtney had been attending to Barnes’ injured foot, and now she sprang up and called aloud in sudden fear. “Polly!”

Jack left the axe where he had dropped it and started off hot-footed to catch up with the escaping animals. The snow impeded the hoofs of the leading horse, and he soon found that running away in the teeth of a blizzard was not the fun it was in town, when he began to cut capers for amusement to those around. He had not galloped more than a hundred yards before he began to breathe hard. The high altitude had a lot to do with this, too, but the beast knew nothing of altitudes. In the length of a few more yards he was glad enough to halt and try to catch his breath. This, naturally, stopped the other horses that were being dragged willynilly at the heels of their leader.

Jack ploughed through the broken snow as fast as he could lift his feet out of the clinging drifts, and after a hard sprint he caught up to the sweating animals. But now! how to turn them about? That was another problem, and he gazed in despair at the closely standing aspens which lined the sides of the trail.

Polly made a horn of her cupped hands and shouted at him. “Only one thing to do, Jack, and that is—cut down the aspens over there, instead of here. We’ll have to come and help you, and leave Mrs. Courtney with the guide; we’ll pick them up after we get the horses turned about.”

Jack signified he had understood, and then, holding fast to the bridle of the leading animal, he waited until Polly brought the axe. The other girls followed in Polly’s tracks, and, after a tiresome hike, they all went to work to remove the obstructing aspens. Jack now wielded the axe, with a zeal he had been unconscious of possessing, and the three girls worked in breaking down the younger growth of trees and throwing them back upon the trodden trail; since they would not return that way, but would lead the horses about the short turn they were making through the woods, it made little difference.

No one stopped to eat, though all were half-famished and half-frozen, as well. Mrs. Courtney tried to keep Barnes from being chilled, by helping him hop around upon one leg, keeping the injured one free from the ground. As Barnes was a heavy young man, and he had to lean upon his companion for support, she was thoroughly tired out by the time the horses were successfully led back through the narrow cleft made in the aspens. In fact, so narrow was it that many a tree-trunk scraped the sides of the horses as they were pulled and pushed and urged to go along to gain the good, though narrow, trail ahead.

This much was successfully accomplished at last, and the young people, who had had to chop and break down the aspens in order to get the horses turned about, heaved a sigh of gratitude when they halted the animals beside the guide.

“Now, our next job will be to hoist Barnes into his saddle,” remarked Jack.

“That is not a difficult thing to do, because I know how to help myself under all unexpected circumstances,” was the cheery reply from the guide. As he spoke, he hopped over to his horse’s side and caught hold of the saddle. At that moment a ray of sun burst through the black snow-clouds and glinted upon the winking eyes of the group of surprised riders.

“Well! can you beat that for contrariness?” cried Polly, glancing angrily up at the breaking storm-clouds.

“Just as we’ve finished our hard labor, to find the blizzard isn’t going to blizz any more!” laughed Eleanor, whimsically.

“If the sun comes out eventually, what are we going to do—go on or turn back?” asked Dodo.

“Oh, we can’t go on with Mr. Barnes in this condition. We must return as quickly as possible and see that he has surgical attention,” declared Mrs. Courtney.

“Well, it is a great disappointment, not to see the view we were led to expect from the summit of the peak, but I am so tired out with shoveling snow, and with removing trees from this forest, that I’m just as well pleased if we get back to Flagstaff and can roll over into a warm bed,” was Polly’s verdict.

“Reckon you’re right, Poll!” agreed Jack, as he sprang up into his saddle.

The rest of the afternoon was spent in carefully riding back to the cabins where the guides lived while the trails remained open. Here the old mountaineer who did the cooking for the men during the season, soon had steaming coffee, with bacon and eggs, ready to serve.

The girls would not have believed how good greasy eggs fried in bacon fat could taste, until that afternoon. Jack commented upon the evident relish with which they ate whatever was placed before them.

“No wonder!” laughed Polly, seeking carefully for the last crumb of black bread, “wood-cutters always come in after a hard day’s work, with appetites like ravening wolves.”

“That’s us!” declared Dodo, ungrammatically. Then she smacked her lips with relish over the coffee, while her companions laughed.

Poor Barnes had the worst of that ride, for the small bones of his ankle had been fractured and he would have to keep it in splints for a long time, if he would have it knit well and be as good as ever. But this accident proved to be beneficial for future riders up Humphrey Mountain, for the trail was ordered to be made wider and kept open and clear to protect man and beast in the future.

That evening, at the hotel, Polly remarked to her friends: “One place on the map that we won’t see this trip!”

“I’m not grieving,” laughed Jack. “I’ve seen all of that peak I ever care to.”

“Um! I’m with Jack in that sentiment,” added Eleanor.

“‘Them’s all our sentiments, too!’” giggled Dodo.