YOUTH UNEMPLOYMENT

In the introduction to this book we quoted John Ruskin, British social commentator (1819-1900) as saying: “Let us reform our schools and we shall need little reform necessary in our prisons”. Unless you have been on an extended visit to Mars you will know that both of these institutions are under severe pressure in the not-so-new South Africa.

The prisons are overflowing. The justice system cannot cope. Offenders enjoy benign bail conditions because there is no room at the inn. This allows them to become repeat offenders without even being incarcerated. Our South African lives, Black, White, Coloured and Asian are worth less than a cell phone. Is this the life God planned for us? Do we ordinary South African citizens, Black, White, Coloured and Asian, deserve this?

I think not.

In a report on education, Jonathan Jansen recently said in a national newspaper: “A five-minute walk through the school and all South Africa’s education problems are on display. The roof is rusted throughout; the toilets stink; litter is everywhere; one teacher is dozing inside a noisy class; and a number of children can be found drifting on a playground. On to the next school and things get worse. Children are outside washing the cars of their teachers, and a number of adults occupy the school grounds, selling their wares. The school is literally falling apart, with huge holes in the ceiling of the room in which I am to speak. By the time we get to the final school the pattern is familiar; filthy grounds, lacklustre teachers, crumbling infrastructure and poor results”.

As ordinary South African citizens, Black, White, Coloured and Asian, should we accept this appalling excuse for the education of our precious youth?

I think not.

A 15-month study of township youths’ morality has concluded that most of them are good kids, but many are neglected. Adult guidance is what is missing from their part-schooled, part-parented lives. Sharlene Swartz, a fellow at the Human Sciences Research Council conducted the research at a school in Cape Town amongst pupils aged between 15 and 19 years. Swartz believes the moral makeup of township youth needs to be the focus of educational attention, and has called for innovative interventions by policy makers and educators.

Skollie Vuma, when interviewed in the study on his take on corruption, said: “If apartheid didn’t affect my parents, then maybe we wouldn’t be staying in that shack house… maybe if my parents were staying in the suburbs, I wouldn’t know about those things (drinking, drugs and criminal behaviour) and I wouldn’t see so many people smoking dagga”.

Can you argue with that lost young South African’s view? Young Vuma’s plight is borne out by a recent survey, says Servaas van der Berg of the Department of Economics at Stellenbosch University. An analysis of the earnings of employed matriculants aged 20 to 24 showed that those from households headed by a parent without matric earned on average R2,262 per month, while households with a matriculated head earned on average R4,512 per month. The correlation between education and relative poverty is plainly evident in this small sample.

Unisa’s Bureau of Market Research in their report on personal income patterns and profiles says that there is a strong correlation between education and income levels. Adults with no schooling earn R50, 000 per year or less, while incomes between R300,000 and R500,000 per annum were earned by people with a secondary or tertiary qualification.

The survey further notes that South Africa ranked last among 45 countries in 2006 in terms of literacy and mathematics. Further, one white child in 10 and one black child in 1,000 achieves an A aggregate matriculation. How, in good conscience, are we as a country able to dream of an African Renaissance and spend billions of taxpayers’ funds pursuing this frivolous ideal, when we are last in the class?

The Cape-based Centre for Higher Education and Transformation, together with the University of the Western Cape’s Further Education and Training Institute, in their Ford Foundation funded research, found recently that nearly three million of South Africa’s 6,7 million youngsters between ages 18 to 24 were, in 2007, neither employed nor receiving any form of post-matric training or higher education. Of this idle population 41 percent are Coloured and 44 percent are African.

The state of play 15 years into the not-so-new South Africa may be seen from the 2009 matriculation results, as reported by the Centre for Education Policy Development:

1998 Generation of Scholars Numbers Percent

Passed matric in 2009 334,609 22%

Failed matric in 2009 217,331 14%

Wrote matric in 2009 551,940 36%

Dropped out 1998 through 2009 998,850 64%

Entered school in 1998 1,550,790 100%

South Africa is recognised as one of the biggest spenders on education in the world, forking out about five percent of Gross Domestic Product. Despite this, it remains one of the poorest achievers by international standards. How can we, as a nation, possibly tolerate a drop-out rate of 64 percent? This is far worse than the 39 percent fail rate for those who actually wrote the matric exam in 2009. Education expert, Graeme Bloch, says: “It’s a ticking time bomb. An enormous number of children will not be doing very much with their lives and will probably not get a second chance at basic education”.

How the poor South African economy has continually absorbed these horrific numbers of lost children each year, over the last 15 years, is indeed a miracle. Certainly, this aggregate of lost children is growing to become a very significant portion of the Rainbow Nation.

Graeme Bloch continues: “It will take about 30 years to fix this problem. By then the dropouts from the 1998 generation will have been unemployed for most of their adult lives”.

Veteran journalist, Allister Sparks, further highlights this debacle: “We have betrayed a whole generation of young people and left more than a million of them with no prospects for the future. That is failing in a sacred responsibility that the ANC had to the youth of this country. For it was the youth, more than anyone else, who fought the real war of liberation in this country.

They represent the future, and to fail them is to ensure the failure of the future of South Africa.

A subject so grave it must surely top the ‘to do list’ of the President. Alas no. He gives credence instead to the notoriously retrogressive SA Democratic Teachers’ Union (SADTU) backed by that ever grasping dalliance partner, Cosatu. Over the past five years SADTU has the dubious distinction of topping the list of days lost through strike action. Of all working days lost in this period, 42 percent were incurred by our infamous teachers’ union.

Andrew Levy, veteran labour specialist, says: “We hope one day teachers will realise their moral obligation and use strikes responsibly”. Servaas van den Berg, Professor of Economics at Stellenbosch University, adds: “Strike action puts at risk the chances of children getting a good education”. And economist Mike Schussler goes as far as saying: “SADTU is keeping apartheid alive”.

So, let me try to understand. The future of South Africa lies in the hands of the youth of the nation. The key to that event lies in the education of that youth. The success of that endeavour depends on teachers being at school to teach and having the moral obligation and incentive to teach.

And finally, the government must prioritize education above all else. That scenario seems too simple. Perhaps those entrusted to execute these plans have a greedier and more devilish agenda?

And as Rome continued to burn, the modern-day Nero and his merry fiddlers continued to fiddle – late into the night.

Editorial: As the ANC burns, we burn with it

02 Jun 2017

Head of Stats SA - Pali Lehohla.

When Pali Lehohla, statistician general at Statistics South Africa, unpacked the quarterly labor force survey on Thursday, he all but confirmed that South Africa is indeed hurtling towards a recession.

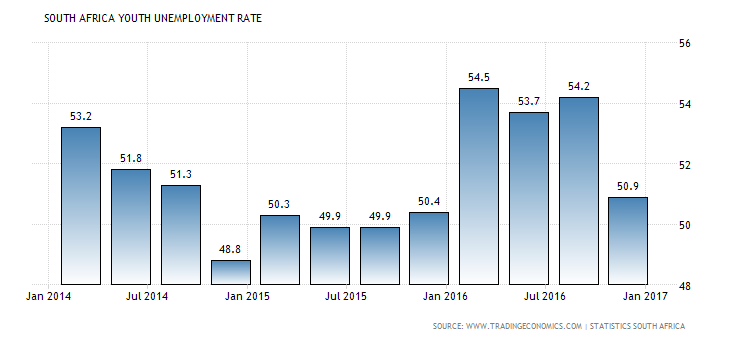

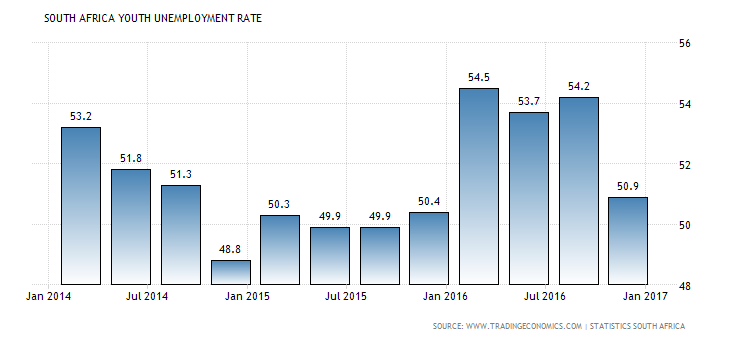

The most urgent statistic for the rest of us to mull over right now is this: South Africa’s rate of unemployment in the first quarter of 2017 increased by 1.2 of a percentage point to 27.7% – the highest figure since September 2003.

The expanded unemployment rate – which includes those who wanted to work but did not look for work – increased by 0.8 of a percentage point, or 391 000 people, from 35.6% to 36.4% of the population. That amounts to a total of 9.3-million people who were unemployed but who wanted to work in the first quarter of 2017.

And there is little respite in sight.

The rating agencies’ downgrading of the country to junk status earlier this year has further eroded levels of investor confidence. With little new investment expected, the economy is not likely to expand sufficiently to create jobs for nearly 10-million people.

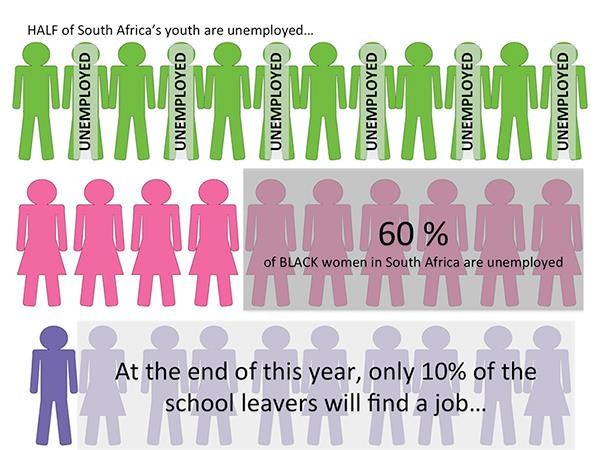

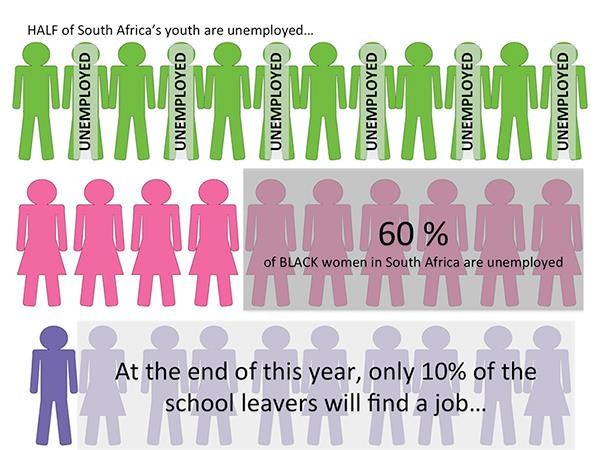

The rhetoric of radical economic transformation fails to address how President Jacob Zuma has himself been complicit in the systematic impoverishment of the South African people – most of them young black women.

It certainly is tempting to point out that it is under Zuma that R100-billion of value was wiped off funds that invest money with the Public Investment Corporation (PIC)– the fund with the greatest potential for social transformation – in just two days. It is tempting to point out that it is under Zuma that the ANC has lost control of three more metros. It is tempting to point out that it is under Zuma that the ANC has expunged some of its most promising leaders, leaving the party as easy pickings for a nefarious, self-obsessed elite.

We cannot, however, pin this on Zuma alone.

It is successive ANC governments that have promised jobs and then left millions of South Africans with little hope of securing employment. It is successive ANC governments that have ensured the public education system is so severely strained, and so poor in its outputs, that it is not likely to equip South Africans with the skills they need to thrive. It is, after all, successive ANC governments that have allowed a culture of waste, corruption and nepotism to fester under their watch.

It is the ANC that is the problem.

Despite an avowed sentiment of dissatisfaction with Zuma within the party, the president and his merry band of loyalists have all but secured his survival until the next election. And here, too, it is the party itself that failed to hold its leader to account.

So, when trade union federation Cosatu’s affiliates told the Mail & Guardian this week that they would cast their ballots elsewhere should Zuma’s heir apparent, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, become the next ANC leader, the severity of the ANC’s problems became ever more profoundly clear.

The ANC has been cannibalized, so Mmusi Maimane was right to pronounce the death of the ANC in Parliament this week. There is no saving the ANC, except to watch it burn. It’s just that millions of South Africans are burning with it.