STATE CAPTURE

All six of my previous books have had the decline of South Africa from Western Democracy to African Kleptocracy as a background theme.

On April Fool’s Day 2017, with the fall of the Treasury, South Africa finally became the fifty fourth country on the African Continent to succumb to the ‘African Way’.

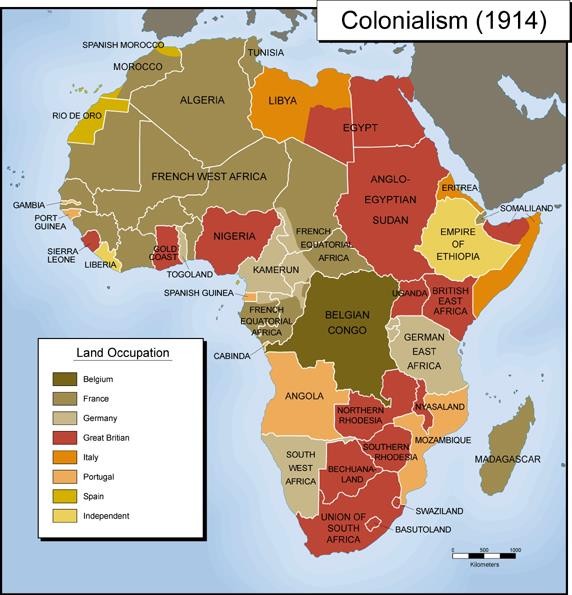

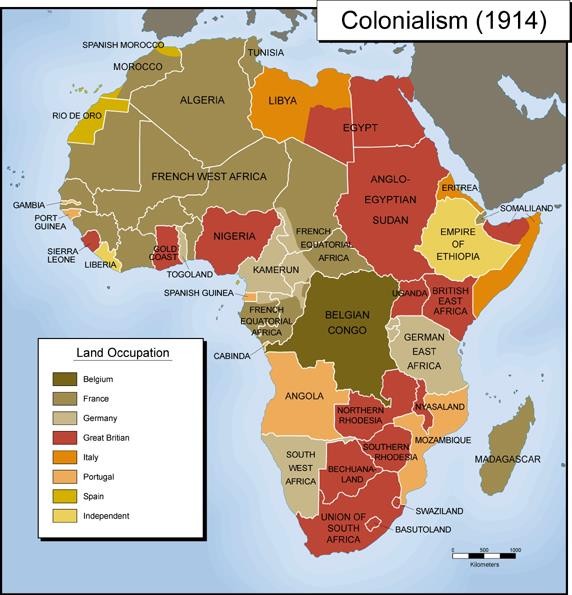

This is not surprising when you read extracts from William Woodruff’s ‘A Concise History of the Modern World’ and specifically the chapter ‘The Decolonization of Africa’.

William Woodruff is Graduate Research Professor (Emeritus) in Economic History at the University of Florida, Gainesville. He holds degrees from the Universities of Oxford, London, Nottingham and Melbourne (honorary).

He says ‘The declaration of principles by Churchill and Roosevelt in the Atlantic Charter in 1941, with its promise of self-determination and self-government for all, heralded the end of European colonization in Africa. As the Second World War progressed, a new generation of black leaders, intent on obtaining self-rule, emerged out of the native resistance movements’.

‘By and large, the European nations were as glad to surrender political power as the native leaders were to assume it. When one compares the struggle for independence in Asia, African independence – with the exception of Algeria – was won quietly and with relatively little bloodshed; in some cases, it was thrust upon those who sought it’.

‘When one considers African traditions, and the desperate economic conditions of so many Africans, it was perhaps foolish to have expected Africa to adopt Western ways. With a tradition of hierarchical tribalism, Africa has never been disposed to democratic politics. While the number of democracies in the world is on the rise, Africa was not much closer to democratic rule in 2005 than it was in 1950. What the West understands as freedom of the individual under the law has still to be achieved. Where the rule of law has gained a foothold, it has often been broken by democratic leaders’.

‘In many African countries, free elections and a free press (as the West would define them) are not tolerated; nor is an independent judiciary.

The Western idea of freely held multi-party elections is not widespread. Too many governments do not have a ‘loyal opposition’; they have political enemies. Elections are a means of conserving power, not introducing democracy. In a continent where power is personalized, few presidents have ever accepted defeat in an election. Concentrated rather than shared, power is the ‘African Way’.

‘Having removed the colonial yoke, Africans now bear a yolk of their own making’. ‘Independence from colonial powers has not only brought widespread violence; it has brought a deterioration of Africa’s economic lot. It is the world’s poorest, most indebted continent; the debt repayments of some countries exceed the amount being spent on health and education’.

‘By holding the West responsible for the continent’s extreme poverty, internal wars, tribalism, fatalism and irrationality, autocracy, disregard for the future, stifling of individual initiative, military vandalism, staggering corruption, mismanagement and sheer incompetence, Africans are indulging in an act of self-deception’

‘A similar colonial background has not prevented certain Asian countries from achieving rapid economic development. Africa cannot hope to escape from its present economic and political dilemmas by placing the blame on others’

‘If Africa is to pay a necessary and constructive role in the world community, it must first rediscover itself. Only Africans really know where they have been and where they might hope to go. They do not have to have Western values and Western goals to become economically viable; their cultural values are too deeply planted for that to happen. Western values and goals may be entirely inappropriate for them. Nor does their performance have to be judged by Western standards. Ultimately, African intrinsic values and goals must prevail. African ideas, confidence and resolve, rather than foreign leadership and foreign aid - much though it is needed – will eventually determine Africa’s future. The continent’s human qualities and its rich natural resources offer great hope’.

What is State Capture

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

State capture is a type of systemic political corruption in which private interests significantly influence a state's decision-making processes to their own advantage.

The term 'state capture' was first used by the World Bank (c 2000) to describe the situation in central Asian countries making the transition from Soviet communism. Specifically, where small corrupt groups used their influence over government officials to appropriated government decision making to strengthen their own economic positions, these groups would later become known as oligarchs.

Allegations of state capture have led to protests against the government in Bulgaria in 2013-2014, and have caused an ongoing controversy in South Africa which started in 2016.

Defining state capture

The classical definition of state capture refers to the way formal procedures (such as laws and social norms) and government bureaucracy are manipulated by private individuals and firms so as to influence state policies and laws in their favour. State capture seeks to influence the formation of laws to protect and promote influential private interests. In this way, it differs from most other forms of corruption which instead seek selective enforcement of already existing laws.

State capture may not be illegal, depending on determination by the captured state itself, and might be attempted through private lobbying and influence. The influence may be through a range of state institutions, including the legislature, executive, ministries and the judiciary, or through a corrupt electoral process. It is thus similar to regulatory capture but differs through the wider variety of bodies through which it may be exercised and because, unlike regulatory capture, the private influence is never overt, and cannot be discovered by lawful processes, since either (or all) the legislative process, judiciary, electoral process and/or executive powers have already been influenced and subverted by the private special interests.

A distinguishing factor from corruption is that, while in cases of corruption the outcome (of policy or regulatory decision) is not certain, in cases of state capture the outcome is known and is highly likely to be beneficial to the captors of the state.

Also, in cases of corruption (even rampant) there is plurality and competition of 'corruptors' to influence the outcome of the policy or distribution of resources. However, in state capture, decision-makers are usually more in a position of agents to the principals (captors) who function either in monopolistic or oligopolistic (non- competitive) fashion.

State capture examples Bulgaria

Main article: 2013–14 Bulgarian protests against the Oresharski cabinet

Protests in Bulgaria in 2013–14 against the Oresharski cabinet were prompted by allegations that it came to power due to the actions of an oligarchic structure (formerly allied to Boyko Borisov) which used underhand manouevres to discredit the GERB party.

Latin America

Instances were politics have been ostensibly deformed by the power of drug barons in Colombia and Mexico are also considered as examples of state capture.[1]

South Africa

Main article: Gupta family

In 2016 there were allegations of an overly close and potentially corrupt relationship between the wealthy Gupta family and the South African president Jacob Zuma, his family and leading members of the African National Congress (ANC). South African opposition parties made claims of 'state capture' following allegations that the Guptas were offering Cabinet positions and influencing the running of government. These allegations were made in light of revelations by former MP Vytjie Mentor and Deputy Finance Minister Mcebisi Jonas that they had been offered Cabinet positions by the Guptas at the family's home in Saxonwold, Johannesburg.

Former ANC MP Vytjie Mentor claimed that in 2010 the Guptas had offered her the position of Minister of Public Enterprises, provided that she arranged for South African Airlines to drop their India route, allowing a Gupta linked company (Jet Airways) to take on the route. She said she declined the offer, which occurred at the Guptas' Saxonwold residence, while President Zuma was in another room. This came a few days before a cabinet reshuffle in which minister Barbara Hogan was dismissed by Zuma. The Gupta family denied that the meeting took place and denied offering Vytijie a ministerial position. President Zuma claimed that he had no recollection of Vytjie Mentor.

Deputy Finance Minister Mcebisi Jonas said he had been offered a ministerial position by the Guptas shortly before the dismissal of Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene in December 2015, but had rejected the offer as "it makes a mockery of our hard-earned democracy‚ the trust of our people and no one apart from the President of the Republic appoints ministers".[ The Gupta family denied offering Jonas the job of Finance Minister.

The Guptas' alleged "state capture" was investigated by Public Protector Thuli Madonsela. President Zuma and Minister David van Rooyen applied for a court order to prevent the publication of the report on 14 October 2016, Madonsela's last day in office. Van Rooyen's application was dismissed, and the President withdrew his application, leading to the release of the report on 2 November 2016. The report recommended establishment of a judicial commission of enquiry into the issues identified, including a full probe of Zuma's dealings with the Guptas, with findings to be published within 180 days.

Zuma and van Rooyen denied any wrongdoing. The Guptas' lawyer disputed the evidence in the report, and the Gupta family denied any wrongdoing and welcomed the opportunity to challenge the report's findings in an official inquiry.

On 25 November 2016, Zuma announced that the Presidency would be reviewing the contents of the state capture report. He said it "was done in a funny way" with "no fairness at all," and argued he was not given enough time to respond to the public protector.

BETRAYAL OF THE PROMISE: HOW SOUTH AFRICA IS BEING STOLEN

May 2017

State Capacity Research Project

Convenor: Mark Swilling Authors

Professor Haroon Bhorat (Development Policy Research Unit, University of Cape Town),

Dr. Mbongiseni Buthelezi (Public Affairs Research Institute (PARI), University of the Witwatersrand),

Professor Ivor Chipkin (Public Affairs Research Institute (PARI), University of the Witwatersrand),

Sikhulekile Duma (Centre for Complex Systems in Transition, Stellenbosch University),

Lumkile Mondi (Department of Economics, University of the Witwatersrand),

Dr. Camaren Peter (Centre for Complex Systems in Transition, Stellenbosch University),

Professor Mzukisi Qobo (member of South African research Chair programme on African Diplomacy and

Foreign Policy, University of Johannesburg),

Professor Mark Swilling (Centre for Complex Systems in Transition, Stellenbosch University),

Hannah Friedenstein (independent journalist - pseudonym)

This report suggests South Africa has experienced a silent coup that has removed the ANC from its place as the primary force for transformation in society. Four public moments define this new era: the Marikana Massacre on 16 August 2012; the landing of the Gupta plane at Waterkloof Air Base in April 2013; the attempted bribing of former Deputy Minister of Finance Mcebisi Jonas to sell the National Treasury to the shadow state in late 2015; and the Cabinet reshuffle in March 2017.

Resistance and capture is what South African politics is about today. Commentators, opposition groups and ordinary South Africans underestimate Jacob Zuma, not simply because he is more brazen, wily and brutal than they expect, but because they reduce him to caricature. They conceive of Zuma and his allies as a criminal network that has captured the state. This approach, which is unfortunately dominant, obscures the existence of a political project at work to repurpose state institutions to suit a constellation of rent-seeking networks that have been constructed and now span the symbiotic relationship between the constitutional and shadow state.

This is akin to a silent coup.

This report documents how the Zuma-centred power elite has built and consolidated this symbiotic relationship between the constitutional state and the shadow state in order to execute the silent coup. At the nexus of this symbiosis are a handful of the same individuals and companies connected in one way or another to the Gupta- Zuma family network. The way that this is strategically coordinated constitutes the shadow state. Well-placed individuals located in the most significant centres of state power (in government, SOEs and the bureaucracy) make decisions about what happens within the constitutional state. Those, like Jonas, Vytjie Mentor, Pravin Gordhan and Themba Maseko who resist this agenda in one way or another are systematically removed, redeployed to other lucrative positions to silence them, placed under tremendous pressure, or hounded out by trumped up internal and/or external charges and dubious intelligence reports. This is a world where deniability is valued, culpability is distributed (though indispensability is not taken for granted) and where trust is maintained through mutually binding fear.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, the shadow state is not only the space for extra-legal action facilitated by criminal networks, but also where key security and intelligence actions are coordinated.

It has been argued in this report that from about 2012 onwards the Zuma-centred power elite has sought to centralise the control of rents to eliminate lower-order, rent-seeking competitors. The ultimate prize was control of the National Treasury to gain control of the Financial Intelligence Centre (which monitors illicit flows of finance), the Chief Procurement Office (which regulates procurement and activates legal action against corrupt practices), the Public Investment Corporation (the second largest shareholder on the Johannesburg Securities Exchange), the boards of key development finance institutions, and the guarantee system (which is not only essential for making the nuclear deal work, but with a guarantee state entities can borrow from private lenders/banks without parliamentary oversight). The cabinet reshuffle in March 2017 has made possible this final control of the National Treasury

Executive Summary

Betrayal of the Promise: How the Nation is Being Stolen

The capture of the National Treasury, however, followed five other processes that consolidated power and centralised control of rents:

- The ballooning of the public service to create a compliant politically-dependent, bureaucratic class.

- The sacking of the ‘good cops’ from the police and intelligence services and their replacement with loyalists prepared to cover up illegal rent seeking (with some forced reversals, for example, Robert McBride)

- Redirection of the procurement-spend of the SOEs to favour those prepared to deal with the Gupta-Zuma network of brokers (those who are not, do not get contracts, even if they have better BEE credentials and offer lower prices).

- Subversion of Executive Authority that has resulted in the hollowing out of the Cabinet as South Africa’s pre-eminent decision-making body and in its place the establishment of a set of ‘kitchen cabinets’ of informally constituted elites who compete for favour with Zuma in an unstable crisis-prone complex network

- The consolidation of the Premier League as a network of party bosses, to ensure that the National Executive Committee of the ANC remains loyal. At the epicentre of the political project mounted by the Zuma centred power elite is a rhetorical commitment to radical economic transformation. Unsurprisingly, although the ANC’s official policy documents on radical economic transformation encompass a broad range of interventions that take the National Development Plan as a point of departure, the Zuma-centred power elite emphasises the role of the SOEs, particularly their procurement spend. Eskom and Transnet, in turn, are the primary vehicles for managing state capture, large-scale looting of state resources and the consolidation of a transnationally managed financial resource base, which in turn creates a continuous source of self-enrichment and funding for the power elite and their patronage network.

In short, instead of becoming a new economic policy consensus, radical economic transformation has been turned into an ideological football kicked around by factional political players within the ANC and the Alliance in general who use the term to mean very different things.

The alternative is a new economic consensus.

Since 1994 there has never been an economic policy framework that has enjoyed the full support of all stakeholders. A new economic consensus would be a detailed programme of radical economic transformation achieved within the constitutional, legislative and governance framework. The focus must be a wide range of employment- and livelihood-creating investments rather than a few ‘big and shiny’ capital-intensive infrastructure projects that reinforce the mineral-energy-complex. For this to happen, an atmosphere of trust conducive for innovation oriented partnerships between business, government, knowledge institutions and social enterprises is urgently required. None of this is achievable, however, until the shadow state is dismantled and the key perpetrators of state capture brought to justice.

The major difference between most of mankind and the not-so-smart is the latter’s inability to appreciate the consequences of their actions. As a result, the cerebrally disadvantaged happily tolerate risk levels which sober minds avoid. They truly are fools rushing in. Think of someone permanently inebriated with a steering wheel in their hands. They can often get away with a lot of swerving and close shaves before the accident happens. During this time, uninformed observers might even refer to them as “strategically brilliant.” But once disaster hits, everyone realizes a sticky end was inevitable. Those who crudely gambled on capturing the South African State are examples of this reality. Their malfeasance is easily exposed by keener minds. Latest blow for the plunderers is the excellent “Betrayal of the Promise: How the Nation is being stolen” publication by the State Capacity Research partnership. Released last night, the 63 page report by a collaboration of leading academics and researchers joins the dots in the way Pravin Gordhan has urged upon the rest of us. It provides proof of issues raised publicly by the likes of Thuli Madonsela, Mcebisi Jonas and Paul O’Sullivan. The weight of evidence is now overwhelming. The consequences obvious. Hope springs. – Alec Hogg

Betrayal of the promise: How South Africa is being stolen – Executive Summary

This report suggests South Africa has experienced a silent coup that has removed the ANC from its place as the primary force for transformation in society. Four public moments define this new era: the; the landing of the Gupta plane at Waterkloof Air Base in April 2013; the attempted bribing of former Deputy Minister of Finance Mcebisi Jonas to sell the National Treasury to the shadow state in late 2015; and the Cabinet reshuffle in March 2017. Resistance and capture is what South African politics is about today.

Commentators, opposition groups and ordinary South Africans underestimate Jacob Zuma, not simply because he is more brazen, wily and brutal than they expect, but because they reduce him to caricature. They conceive of Zuma and his allies as a criminal network that has captured the state. This approach, which is unfortunately dominant, obscures the existence of a political project at work to repurpose state institutions to suit a constellation of rent-seeking networks that have been constructed and now span the symbiotic relationship between the constitutional and shadow state. This is akin to a silent coup.

This report documents how the Zuma-centred power elite has built and consolidated this symbiotic relationship between the constitutional state and the shadow state in order to execute the silent coup.

At the nexus of this symbiosis are a handful of the same individuals and companies connected in one way or another to the Gupta-Zuma family network. The way that this is strategically coordinated constitutes the shadow state. Well-placed individuals located in the most significant centres of state power (in government, SOEs and the bureaucracy) make decisions about what happens within the constitutional state. Those, like Jonas, Vytjie Mentor, Pravin Gordhan and Themba Maseko who resist this agenda in one way or another are systematically removed, redeployed to other lucrative positions to silence them, placed under tremendous pressure, or hounded out by trumped up internal and/or external charges and dubious intelligence reports. This is a world where deniability is valued, culpability is distributed (though indispensability is not taken for granted) and where trust is maintained through mutually binding fear. Unsurprisingly, therefore, the shadow state is not only the space for extra-legal action facilitated by criminal networks, but also where key security and intelligence actions are coordinated.

It has been argued in this report that from about 2012 onwards the Zuma-centred power elite has sought to centralize the control of rents to eliminate lower-order, rent-seeking competitors.

The ultimate prize was control of the National Treasury to gain control of the Financial Intelligence Centre (