CHAPTER IX

CATHCART, PROCTOR

Hugh thrust his body through the window again. No one was in sight along the front. By leaning well out he could see the lighted windows of Number 29 Lothrop, and he smiled as he reflected that Bert was probably wondering what had become of his roommate. Then he viewed the next window, some five feet distant.

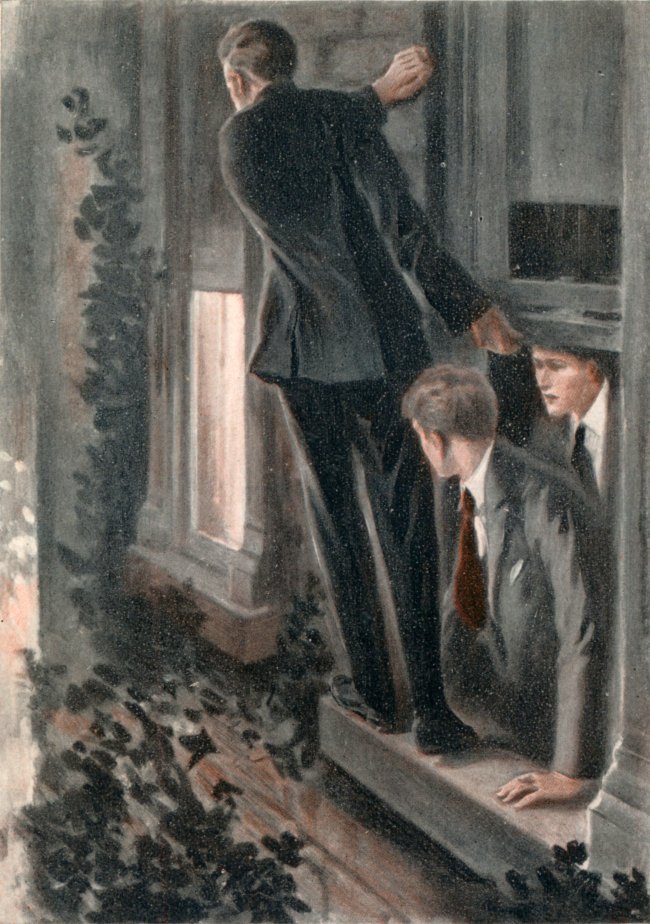

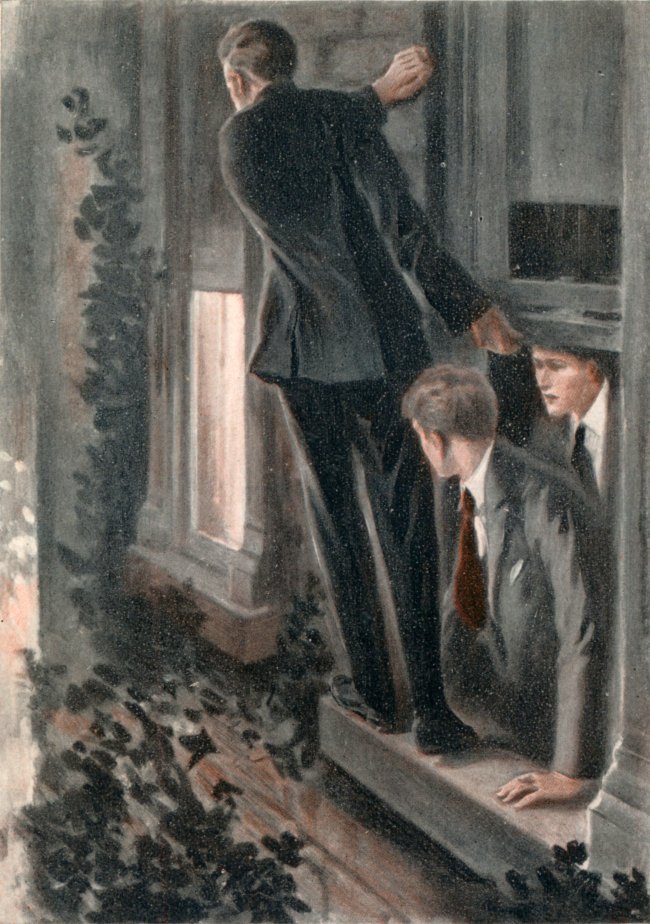

The sills were broad and extended a few inches beyond the casements, but Hugh doubted that he would be able to stretch his legs far enough to reach, even could he find anything to hold on to. He crawled out on the sill, to the alarm of the hysterical Twining, and, while keeping a firm hold of the window sash, felt about over the bricks in search of some projection to cling to. In the end he had to return to the classroom defeated. That avenue of escape was out of the question. The distance to the ground didn’t look far, but it must be, he realized, about twenty feet, and that meant a drop of fifteen feet, enough to shake one up considerably. But by knotting their coats together it might be done.

“That avenue of escape was out of the question.”

“Let me have your coats, fellows,” he said, pulling his own off. They emptied the pockets first, stowing the treasures away in their trousers, and then handed the garments over. Hugh tied the three sleeve to sleeve, testing each knot, but when the task was completed the result was disappointing, for the improvised rope measured only about five feet in length, a portion of which would have to remain across the sill and, since there was nothing to tie it to, be held by the juniors. Hugh studied a moment. Then he unbelted his trousers.

“I don’t know how strong these things are,” he said, “but I fancy they’ll stand the strain all right.”

He made a pile of his pocket contents on the floor and knotted the end of one leg to a sleeve of a coat, adding another three feet to the length of the whole.

“Now,” he said cheerfully, “you chaps lay hold of this end, d’ye see? Pull it tight across the sill and you won’t have any trouble. Better sit down on the floor, the two of you, eh? That’s the idea. If you happen to find you can’t hold on, or the thing starts to rip, shout out to me so I can drop. All right now?”

“Y-yes,” replied Struthers doubtfully. “I hope we can hold it!”

“So do I,” replied Hugh grimly as he squirmed his body across the sill. “If you can’t I’ll get down quicker than I fancy. Hold tight now. I’m going to put my weight on it.”

There was a breathless moment of suspense, a moment during which the garments made threatening sounds of giving at the seams, and then Hugh’s head disappeared from sight, the two boys on the floor, feet braced against the wall, held on for dear life and——

“All right!” called a cautious voice from outside. There was a sound of a thud on the bricks and the two juniors simultaneously toppled over backwards.

There was one thing, though, which Hugh had neglected to take into consideration, and that was the probability of the door of School Hall being locked. And when, a bit jarred but quite unhurt, he climbed the steps and tried it, he realized the fact, for the portal was fast. Flattening himself against the door in the shadow, he wondered how he had bettered the condition of his fellow prisoners. They couldn’t follow him by the window, of course, and he, it seemed, was unable to unlock the door to the corridor for them! And, to add interest to the situation, he was sensible of being most unconventionally clad—or, rather, unclad—and didn’t at all relish standing down there in the light and calling up for his trousers to be thrown to him! Meanwhile it was quite within the possibilities that one of the masters might come prowling past and find him!

But something had to be done, and the only thing that occurred to him was to try the windows in the hope of finding one unlatched. So, making certain that no one was in sight, he scuttled from his place of concealment and fled around to the back of the building, where the possibility of being observed at his burglarous task was not so great. It was as dark as pitch back there, but after waiting a minute to accustom his sight to the gloom he was able to discern a window. The sill was at the height of his chin and he wondered whether, even if he was lucky enough to find one unlatched, he could get through it.

The first resisted all his pushing and heaving, and so with the second and third, but when he thrust upward on the next the sash gave readily, but with a fearsome screech that brought his heart to his mouth. After waiting a moment there in the darkness, however, he pushed the window as high as he could reach and then set about the next step. There was nothing to put his feet on, but by getting his arms over the sill he finally managed to work his body up and was soon inside.

The first thing he did was to walk squarely into a desk, and after that it seemed to him hours before he found the door into the corridor. Once outside, his troubles were by no means over, for when he had at last discovered the stairway and descended the first flight he couldn’t think in which direction the room he sought lay. He found it at last, though, turned the key and entered to be greeted by exclamations of mingled relief and displeasure. It was Struthers who expressed relief, and Twining who voiced displeasure.

“Seems to me you took your time,” said the latter. “You must think it’s lots of fun waiting up here——”

“Stow it!” interrupted Hugh, his temper not improved by the adventures of the past ten minutes. “It would serve you jolly right to make you shin down the coats and trousers!”

Twining subsided to mutters and Hugh clothed himself again and rescued his treasures from the floor. When he had finished, the two juniors were already outside.

“You can’t get out the door,” said Hugh. “It’s locked. Keep with me and we’ll slip out a window at the back.”

Twining again demurred, but Struthers promptly sat on him, and a minute later they were outside.

“Now you chaps see if you can find a window unlocked. That’s what I’m going to do. I don’t fancy having it known that I was locked up in School Hall by a lot of fresh lower class chaps. Good night.”

“Good night,” replied Struthers, “and much obliged, Ordway.”

Twining, however, was already creeping off in the darkness, wasting no time on amenities. Hugh felt a strong desire to overtake the youngster and cuff him, but in the end he only shrugged his shoulders and considered his own plight. He carefully closed the window before he turned away to seek Lothrop, and when he did he kept along at the back of Trow to avoid the lights in front. It was well after ten o’clock now and most of the windows were dark, but here and there a light still shone. Mr. Russell’s study on the first floor of Trow was illumined and the curtains were raised, and as Hugh, bending low, passed beneath them he fervently hoped that the Greek master would not take it into his head to approach a casement just then.

The ground floor of Lothrop was given over to public rooms save where, at the farther end, Mr. Rumford had his suite of five rooms and bath. Along the front, between the two entrances, were the library, the common room and the recreation room. At the back were rooms occupied by the superintendent of buildings, Mr. Craig, and by the head janitor, Mr. Crump, a store room and a serving room. The nearer end of the building was taken up by the big dining hall. There were ten windows in the latter and Hugh hoped to find one of the number unlatched. He kept away from the front of the building, for it was disconcertingly light there, and tried the first window on the end. It was fast, however, and so was the next one. Then, to his consternation, the ground began to slope away to the level of the basement floor at the rear of the building, for the kitchen and laundry and various other service rooms were above ground at the back. This brought the third window almost head-high and placed the fourth beyond his reach, and the third window was locked as fast as the others!

He knew nothing of the lay of the land below-stairs and feared to try his fortunes there. Consequently there was nothing to do but risk detection while trying the windows along the front or to ring a door-bell and be reported by Mr. Crump. He had little liking for either alternative and hesitated a moment in the shadow at the corner before emerging into the publicity of the walk which, while deserted, was in plain view of Trow. After all, though, it was, he reflected, no hanging matter, and so he presently emerged quite boldly and, as he passed along the front of the dormitory, tried each window. He had progressed as far as the library when his perseverance was at last rewarded. A sash gave readily to his pressure and in a twinkling he was inside.

Lights in the corridor shone through the open doors and he had no trouble, after he had silently closed the window again and fastened it, in making his way between chairs and tables. At the door nearest to the stairs he paused and looked out. No one was in sight and he swiftly stepped into the corridor, around the corner and through the swinging door that gave on the stairs. He stepped lightly, for he knew that on each floor a master’s bedroom was separated from him by only the thickness of a wall. It was when he had reached the fourth floor and had his hand on the door there that he recalled the fact that directly across the hallway was Number 34, inhabited by Cathcart. Cathcart was a proctor and, so it was said, a most conscientious one. He would have done better, as he now realized, to have gained the floor by the other stairway. However, Cathcart’s door was tightly closed and it was more than likely that Cathcart was sound asleep. So Hugh pushed the swinging portal softly ajar, slipped through and turned along the corridor toward 29. Halfway, he thought he heard a sound behind him, but he didn’t stop or turn. He scuttled into 29—Bert had thoughtfully left the door unlocked—and the instant the latch had slipped into place behind him tore off his coat and fumbled at his belt. The study was empty and dark, but a light shone from Bert’s bedroom and as Hugh hurried into his own apartment a sibilant voice came to him.

“That you, Hugh?”

“Yes.” Hugh was slipping out of his trousers. “I’ll be in in a minute.” He kicked off his shoes and tugged at his tie.

“Where the dickens have you been?” demanded Bert, more loudly. Hugh heard his bed creak and a moment later his bare feet on the floor. And that instant there was a gentle knock on the door.

Hugh flung things from him wildly and dived for his bed. There was silence. Then the knock was repeated, and:

“Winslow!” came Cathcart’s cautious voice from beyond the portal.

After a moment’s hesitation Bert, making a good deal of noise about it, went to the door and flung it open. Hugh, the covers pulled to his chin, held his breath and listened.

“Hello, Wallace.” That was Bert’s voice, surprised and sleepy. “What’s up?”

“Sorry to disturb you,” said Cathcart, pushing past Bert and closing the door behind him, “but someone just came up the stairs and entered this room.”

“Nonsense,” replied Bert, suppressing a yawn. “You probably heard me coming from the bathroom.”

“I didn’t only hear, I saw,” said Cathcart quietly. “You don’t usually visit the bathroom with all your clothes on, I suppose.”

“Not usually, old man, but I couldn’t find my bathrobe. I suppose it’s somewhere around——”

“Is Ordway here?” demanded the proctor.

“I suppose so. We went to bed rather early. Oh, Hugh!”

“Yes?” asked Hugh startledly. “Did you call, Bert?”

“Yes, Cathcart asked if you were here. It’s all right, I guess.”

“If you don’t mind,” murmured Cathcart. He crossed to Hugh’s room and looked in. “Would you mind turning on a light, please, Bert?”

Bert obeyed grumblingly and Cathcart viewed the bedroom. Hugh’s coat lay on the floor near the foot of the bed, his trousers were in front of the dresser, one shoe was on top the trousers and the other a yard away and his shirt hung limply from the footrail. Cathcart took it all in silently and gravely. Then:

“How long have you been in bed, Ordway?” he asked.

“Eh? In bed? Oh, really, I can’t say. What time is it now?”

“You just came in, as a matter of fact, didn’t you?”

“Now look here, Cathcart,” interrupted Bert persuasively. “You’re all wrong, old man. You were dreaming, probably. You can see easily enough that Ordway and I have been in bed for a long time.”

“Does he usually leave his things around like that?” asked the proctor.

“I’m afraid he does. He’s an untidy beggar. You are, aren’t you, Hugh?”

“Perfectly rotten,” replied Hugh cheerfully. “Still, you know, they’re awfully easy to find in case of—er—fire or anything.”

Cathcart smiled wanly. Then he shook his head. “I’m sorry, Ordway,” he said, “but I’ll have to report you. Good night, fellows.”

“But, I say——” began Hugh.

“Look here, Cathcart, have a heart,” pleaded Bert. “You can’t prove anything against him. Why, look at him! You say someone came in here a minute ago. Now you know very well Ordway couldn’t undress in that time!”

“I don’t think I said he entered a minute ago, Bert. However, if Ordway cares to get out of bed and show me that he has his pajamas on——” He viewed Hugh inquiringly.

“Pajamas,” said Hugh indignantly. “Why, I say, I never wear ’em, you know. Beastly uncomfortable things, pajamas.”

“Indeed? May I look in here?” Cathcart opened the closet door. On a hook inside hung a pair of white pajamas with broad blue stripes. “Yours, I think, Ordway?”

Hugh nodded. “Right-o, Cathcart,” he said. “You win. What’s the penalty?”

“I can’t say,” replied the proctor. “I guess it won’t amount to much. I wouldn’t try it again, though, Ordway. They’re rather strict here about being out of hall after hours. Probably you can give a good explanation.”

“Oh, yes, I can,” said Hugh. “Only,” he added under his breath, “I’m switched if I’m going to!”

“I’m sorry, fellows,” said Cathcart again, regretfully. “You know I have to do it, though. Good night.”

“Good night,” said Hugh. “Duty is duty, eh, what?”

“Good night,” returned Bert morosely. “It doesn’t seem to me, Wallace, that you need to be so confounded snoopy, though! Of course you’re a proctor, and all that, but a fellow doesn’t have to go out of his way to look for trouble!”

“I didn’t go out of my way, Bert,” replied Cathcart quietly. “I was awake and heard steps on the stairs and then heard the door pushed open. It was my place to see who was coming up.”

“Then, if you saw him,” said Bert crossly, “what was the good of coming down here and making all this fuss?”

“I saw only his back, and the light was dim. I couldn’t be certain whether it was you or Ordway.”

“Oh!” Bert shot a glance at Hugh, now sitting up in bed and hugging his knees. “Then—then perhaps it will interest you, Wallace, to learn that it wasn’t Ordway, after all! It happened to be me, old man. Put that in your pipe and smoke it!” And Bert viewed the other truculently.

Cathcart smiled gently and shook his head. “That won’t do, Bert,” he said. “Ordway’s owned up, you see.”

“Because he thought I didn’t want to be reported. Besides, he didn’t own up. He only said——”

“Oh, come, Bert! What’s the use?” asked Cathcart. “I know it was Ordway.”

“You do? Even when I say it wasn’t? When I say it was me? You’re mighty smart, aren’t you?”

Cathcart colored and frowned. “Very well,” he said stiffly. “I’ll report you both and you can settle it between you. I’m not quite such a fool as you seem to think, Winslow.”

“I’m not thinking,” replied Bert impolitely.

“Stow it, you chaps,” Hugh broke in. “Be fair, Bert. Cathcart’s only doing what he has to. Much obliged for lying, old chap, but I don’t really mind being reported. It’s all right, Cathcart,” he added reassuringly. “I’m the culprit. Sorry to get you out of bed.”

Bert opened his mouth to speak, thought better of it and shrugged. Cathcart nodded to Hugh and went out. When the door was closed behind him and Bert had turned the key with a venomous click he strode back to Hugh’s room and eyed him wrathfully.

“Why the dickens did you have to butt in?” he demanded. “I could have made him believe it was me in another minute. You haven’t got as much sense as—a—as a——”

“Proctor?” suggested Hugh helpfully. Bert grunted. Hugh threw the clothes aside and swung his feet to the floor. “Mind tossing me those pajamas?” he asked. “Thanks. Now, look here, old chap——”

“You’ll get the very dickens, that’s what you’ll get,” interrupted Bert. “Where were you? How did you get in? Didn’t you know——”

“Yes, old dear, I knew all about it. The degrading truth is that a half-dozen of those beastly lower middle chaps got me and a couple of juniors and locked us up in a classroom in School Hall and I had to shin down the coats and trousers——”

“Shin down the what?”

Hugh smiled. “The coats and trousers. We tied our coats together, you know,—and my trousers, too,—and I got down that way and got in a window at the back and unlocked the door. Then I climbed in through the library.”

“Who were the lower middlers?” demanded Bert hotly.

“Couldn’t see them. Dare say I shouldn’t have known them if I had. It was all over in a jiffy. Someone grabbed me from behind, another chap throttled me and the whole lot pushed me upstairs. Next thing I knew I was locked in that room with a pair of silly juniors named Twining and Struthers. Struthers wasn’t so bad, but Twining was a mean little bounder. I say, you’ve a remarkable looking mouth, old chap!”

“And you’ve got a fine-looking lump over that eye! You’ll make a big hit with the faculty when you’re called up tomorrow!”

“I can say I ran into a door,” replied Hugh untroubledly. “I did once, you know, and had just such a lump.”

“Huh! And I suppose running into the door skinned your knuckles, too?”

“I’ll keep that hand behind me,” laughed Hugh. “Anyway, it was a—a—it was some scrap, wasn’t it?”