CHAPTER XXIII

IN THE LIME-LIGHT

The next morning Bert had apparently forgotten his grievance, although he looked as if he had spent an unrestful night and was fidgety and troubled. Hugh saw little of him until practice time. That afternoon there was only light work for the players and the scrimmage with the second team was short, if lively. Bert and Zanetti started the game and later Bert went out in favor of Hugh, and Zanetti gave way to Vail. The latter seemed as good as ever today and went to work with a will. Hugh, during the time he was in the game, had few opportunities for offensive work but made one good rush of some ten yards when he was let loose outside left tackle. Siedhof played a few minutes in Hugh’s place at the end of the scrimmage.

The first showed the effect of the week’s work and undoubtedly displayed a better defence than theretofore. During the fifteen minutes of actual playing time it scored twice on the second and held its opponent safe.

Football enthusiasm had been rampant for over a week and already two mass-meetings had been held. The third came off that Friday evening and everyone piled into the assembly hall and cheered and sang and whooped things up generally. The Mandolin and Banjo Club occupied the stage and supplied music for the songs. Hugh secretly thought the enthusiasm a bit “made-to-order” as he expressed it. But Hugh had not yet accustomed himself to the idea of organized cheering, which he still considered a trifle ridiculous. But he liked the singing and got into the songs with a will. Captain Trafford predicted victory for the Scarlet-and-Gray; Coach Bonner warned them against overconfidence, and Mr. Smiley quoted much Latin and made them laugh frequently. As a demonstration of loyalty and faith in the team the meeting was a great big success, but it didn’t affect the result of next week’s game the least particle, and so, in Hugh’s mind, was rather a waste of energy. Even Wallace Cathcart attended, and Hugh, to his surprise, caught him with his mouth very wide open and his face very red, cheering like mad. The first and second team players sat together in front and Hugh found himself beside Tom Hanrihan. Hanrihan had displayed a kindly interest in Hugh’s career from the first, and tonight, in a lull between a cheer for Coach Bonner and a song, he said confidentially:

“You’re doing fine, Hobo. Just you keep it up, son, and you’ll have your letter. If you do you’ll be one of the youngest fellows to get it. Bonner can’t keep you out of that game if he wants to, by gum! I sized you up right the first day I saw you; remember? Yes, sir, I liked your style right then, and I told Bonner so, too. I sort of discovered you, Hobo, and if you don’t play a regular star game next week I’ll beat you up!”

Then the mandolins and guitars and banjos struck up “Here We Go!” and Hanrihan and Hugh, the latter referring to the printed slip in his hand, joined in the rollicking refrain:

“Grafton! Grafton! Here we go,

Arm in arm with banners flying!

Pity, pity any foe

When it hears us loudly crying:

‘Grafton! Grafton! Rah, rah, rah!’

All together! Now the chorus:

‘Grafton! Grafton! Rah, rah, rah!’

Victory today is for us!”

Finally, “Nine long ‘Graftons,’ fellows, and put some pep into it!” and then the exodus, with much scraping of settees and laughing and whistling. And afterwards, for Nick and Guy Murtha and Harry Keyes and Hugh, a Welsh rarebit in Nick’s room, made over an alcohol lamp and extremely hot with cayenne pepper!

Southlake Academy was the visitor the next afternoon. Southlake had played Mount Morris earlier in the season and had been soundly drubbed by the score of 19 to 0. But Grafton did not hope to make so good a showing. Nor did she. Southlake was a better team that day than she had been when the Green-and-White had vanquished her, and she soon proved the fact. Coach Bonner started with two substitutes in the line, Hanrihan for Captain Trafford and Willard for Musgrave at center. But Musgrave was hurried in before the game was five minutes old and, although Captain Ted stayed out of the conflict until the third period began, he, too, had to be sent to the relief. The back-field was Blake, Winslow, Vail and Keyes during the first half. Then Weston took Nick’s place, Siedhof went in for Vail, and Leddy played full. Hugh was half sorry and half glad that he was being kept out. He wanted to play hard enough, but he feared that if he did go in it would be in place of Bert, and their relations were strained enough as it was. Bert had hardly spoken a word, civil or otherwise, to his roommate since yesterday’s practice!

There was no scoring on either side until the second period was ten minutes along. Then a lucky fluke gave Grafton the ball on Southlake’s twenty-two yards and she took it over in seven smashing attacks on the center. Keyes missed goal. After that Southlake sprang some open plays which, if they didn’t gain very much ground, considerably worried and exasperated the enemy, who, for a while, didn’t know how to meet them. Still, the nearest Southlake came to a score was getting down to Grafton’s seventeen yards, where she was held for downs, and Keyes kicked out of danger.

Hugh watched the work of the half-backs attentively. Vail was covering himself with glory and Bert was doing considerably better on attack than he had been doing of late, but was frightfully weak on defence. Time after time he was outside the play entirely, while, when he did get into it, he was quite as likely to miss his tackle as make it. Even Hugh, who was desperately anxious to make the best of Bert’s performance, could not fail to see that he was trying the patience of his team-mates and, probably, of Mr. Bonner as well.

Southlake tried two forward passes in the third period and again got within scoring distance. She faked a drop-kick and sent a back on a wide run around Roy Dresser’s end and Roy, for once, was neatly boxed. Bert was the man to stop the runner and Bert made a miserable failure of the attempt, getting his man and then losing him again. Just how Yetter got into the affair was a mystery, but it was the left guard who pulled the Southlake runner down just short of the goal line.

Franklin had been showing distress for some time and now Parker was sent in to play left tackle. At the same time Keyes was put back again, and it was perhaps the big full-back’s presence which stopped the enemy’s advance. Two tries lost her a yard and then she tried a drop-kick and it was Keyes who leaped into the path of the ball and beat it down. Southlake recovered on the fifteen, but she fumbled a minute or two later and the pigskin was Grafton’s.

It was then that the Scarlet-and-Gray showed real form. From her own fifteen-yard line to the middle of the field she went in five plays, Keyes and Roy Dresser bringing off a forward pass that covered more than half the distance, and Vail and Siedhof, and once Keyes, plunging through the line for the balance. A second attempt at a forward pass grounded, but Vail got away outside the Southlake right tackle and reeled off fifteen yards, and from there down to the sixteen Grafton plugged relentlessly. There was a mistake in signals then and some four yards was lost, and Weston elected to try a goal from the field and Captain Trafford went back. But the line weakened somewhere and Ted had no chance to kick and Weston, holding the ball for him near the thirty-yard line, could only snuggle it beneath him and yell, “Down!”

It was then that Coach Bonner beckoned Hugh from the bench. “Go ahead,” he said, “and see what you can do. Tell Weston to use Number 17, Ordway.”

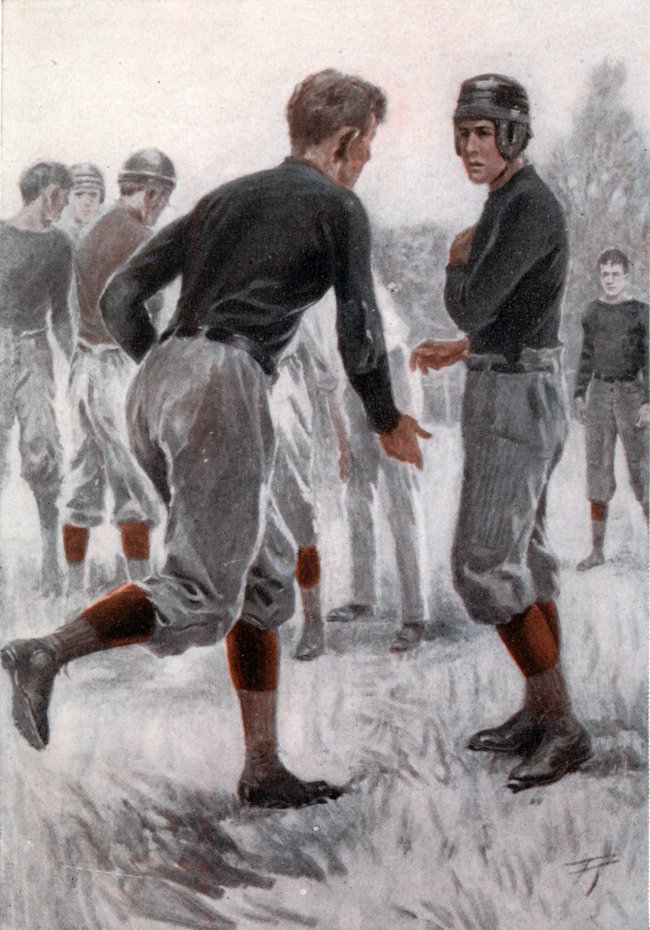

Hugh pulled off his sweater and legged it across with upraised hand, and the stand cheered him. Bert saw him coming and began to tug at his head harness. Then he stopped and waited.

“You’re off,” said Hugh. “May I have that, please?”

“‘You’re off,’ said Hugh. ‘May I have that, please?’”

Bert handed over the leather guard silently, but his expression wasn’t pleasant and Hugh heartily wished that the coach had chosen Zanetti instead of him. But there was no time for regrets then. He whispered his instructions to the quarter-back, repeated them in reply to Captain Ted’s anxious question, pulled the head guard on and sprang into place.

It was third down and about fifteen to go. Weston called the signals, Trafford crossed to the other side of Parker, and Keyes stepped farther back and held his hands out, the halves crouched wide apart, and Weston, stooping behind Musgrave, repeated the signals. Then the ball came back, straight and fast, and Hugh snuggled it in the crook of his arm, started quickly, and, running low and hard, swept past his line on the heels of Siedhof, while Weston and Keyes sped toward the other end. For a moment, a critical length of time just then, Southlake lost sight of the ball. When she had solved the play Siedhof had spun a Southlake tackle from the path, and Hugh had responded to the frantic cry of “In! In!” and was through. Siedhof met the charge of a half, but went down in the encounter, and Hugh, twisting aside, circled out, passed the twenty-yard line, dodged another back and, with the hue and cry close behind, raced over the remaining four trampled white marks and was only stopped when a despairing quarter, wrapping tenacious arms about his legs, brought him to earth well back of the goal line!

Grafton shouted herself hoarse, only letting up for a minute while Keyes directed the ball and subsequently booted it deftly over the bar. After that Grafton played on the defensive for the rest of that period and the next, and, although there were some anxious moments, kept what she had earned. While 13 to 0 didn’t sound as well as 19 to 0, it perhaps stood for quite as much if we consider the fact that Southlake was a stronger team today than when she had met Mount Morris.

Being a hero is a trying business, as Hugh soon discovered. Naturally somewhat retiring, he disliked the sudden publicity that enveloped him, and, being modest, he felt uncomfortable under the praise bestowed on him. Fellows took, he thought, a ridiculous amount of pains to go out of their way to shake his hand or even slap him familiarly on the shoulder and tell him what a wonder he was. He knew very well that he wasn’t a wonder and he didn’t like being called one. He belonged, in part at least, to a people who abhor being conspicuous and who view askance anything savoring of hysteria, and, in spite of his American experiences, he had not lost those feelings. No, on the whole the succeeding week was not a very comfortable one for Hugh. He hoped that after a day or two the school would cease its “bally nonsense,” but he was reckoning without the fact that it was wrought up to a fine state of tension and that the tension increased every hour as the Mount Morris game approached. Consequently the “bally nonsense” continued and Hobo Ordway was never allowed to get out of the lime-light for a minute.

But what troubled Hugh far more than fame and its consequences was Bert’s attitude. After the Southlake game no one, and surely not Bert, doubted for an instant that Hugh had won his position. Another fellow might have swallowed the lump in his throat and smiled, or, being resentful, might have hidden the fact. But not so Bert. He made no secret to Hugh or anyone else that he thought he had been badly treated. Or perhaps, which is more likely, he pretended to think so. At all events, life in Number 29 was difficult and increasingly unpleasant. Bert seldom spoke unless addressed by Hugh and then answered coldly and sneeringly. By the middle of the next week Hugh kept away from the study as much as he could and gave up trying to bridge the chasm. On one occasion, driven out of his usual patience by a surly response, he got thoroughly angry and wanted to fight on the spot. Bert, though, refused to afford him that much satisfaction, telling him sarcastically that if he (Hugh) got hurt and couldn’t play they’d surely lose the game!

Nick and Pop each told Bert that he was making an utter ass of himself, but beyond such satisfaction as they got from airing their opinion, nothing came of it.

There was light work on Monday for the regulars, although those who had not participated strenuously in Saturday’s contest were given the usual medicine. On Tuesday there was a hard practice, and, in the evening, an hour’s signal drill in the gymnasium. The program was the same the next day. That afternoon, Bert, if he still entertained hopes, must have seen the futility of them. For he spent the whole period of scrimmaging on the bench and saw Hugh occupying the place he had looked on as his. Although no official statement to the effect was made by the coaches, it was generally understood that the line-up that day was the one which would face Mount Morris on Saturday. Of course Bert would get into the game for a while beyond the shadow of a doubt, but that brought no satisfaction to him. What increased his sense of injury was the fact that the day before, playing two of the four ten-minute periods against the scrubs, he had held his own with any of them. And he knew now that if he could only get in on Saturday he could play the game of his life!

Perhaps it was a final realization of his defeat that changed his attitude toward Hugh that evening. When both boys were back in the study after the signal work in the gymnasium Bert volunteered a remark in a very casual but surprisingly inoffensive voice. Hugh answered in kind, and, rather embarrassedly, they fell into a discussion of the plays they had rehearsed, of the team’s chances, and of kindred subjects. Then, when Hugh had gone to bed and his light was out, Bert’s voice reached him from his doorway.

“Say, Hugh!”

“Yes?”

An instant’s silence, and then: “I’m sorry I’ve been such a rotter.”

“Oh, that’s all right, Bert!”

“Yes, but——” Another silence, and finally: “It isn’t all right at all! I—oh, well, what’s the use? I’m sorry. I guess that’s the whole yarn. It isn’t your fault, you know, and I—I hope you do fine, old man! Just rip ’em right up the back!”

“Thanks,” replied Hugh in the darkness, “but I wish it were going to be you, Bert, honest! I don’t want to play a mite. I’m beastly sorry I—I——”

“Oh, rot!”

“But I am, though! I feel an awful ass, if you know what I mean; butting in like this and doing you out of your place on the team when I can’t begin to play the way you do, old chap! It—it’s piffling poppycock! That’s what it is! Piffling poppycock!”

He appeared to derive a lot of satisfaction from the phrase, and Bert heard him mutter it over again to himself as he felt his way into the room and sat on the foot of Hugh’s bed.

“No,” he said, tucking his feet up out of the draft from the open window, “no, that’s not true. You play just as good a game as I ever did, Hugh. You can’t get around that. And what’s a heap more, you’re steady. I never was. I’d play good enough one day and then be perfectly rotten the next, maybe. What gets me, though, is how the dickens you ever learned in only about eight weeks!”

“Oh, I don’t know. And, anyhow, that’s got nothing to do with it. I never imagined that I’d get in your way, Bert. If I had I’d never have gone in for the silly game. Now look what’s happened!”

“Well, what has happened? I’m out and you’re in because you deserve to be. Besides, there’s another year coming, isn’t there? Football doesn’t stop after Saturday, you know.”

“That’s taking it mighty well,” said Hugh warmly. “But—just the same I don’t like it. It makes me feel an awful rotter, an out-and-out rotter, old chap! If there was any way to—to—to back out——”

“Don’t be a chump! There isn’t, and if there was you’d have no right——”

“Why not? I know there isn’t, of course, but I don’t see why I shouldn’t have the say about playing. Of course I can’t go to Mr. Bonner and say ‘Look here, you know, I’ve changed my silly mind and don’t think I’ll play Saturday.’ That wouldn’t do, of course. But, just the same, it’s tommyrot to say I haven’t the right, you know.”

“You haven’t,” declared Bert decidedly. “The team needs you and it’s up to you to do your level best.”

“My level best is no better than yours, though; not so good, in fact. How do you know that I won’t have stage-fright Saturday and drop the ball or—or try to swallow it? You can’t make me believe that if something happened so I couldn’t play you wouldn’t do just as well and probably better than I would!”

“I don’t know what I’d do,” answered Bert thoughtfully. “Yes, I do, though, old man. I’ve got a perfectly magnificent hunch that I’d play good ball if I got a chance. But that’s got nothing to do with it. I shan’t have the chance unless Bonner puts me in for a little while at the end. He probably will, you know; after we’ve got the thing cinched or we’re so far behind that nothing matters!”

“Well, there it is, then!” said Hugh triumphantly. “You know what you can do and I don’t! What I say is——”

Bert laughed. “Oh, you dry up and go to sleep, Hugh. It’s all right, old man. I did act like a beast, and I’m sorry, and I beg your pardon. And that’s all of that, I guess. For the rest of it, I hope you’ll play a rattling good game, Hugh, and if I’m to substitute you I hope I won’t get in at all. Good night!”

“Well, but—now hold on, old dear! I want to tell you——”

“Not tonight. It’s after eleven. Go to sleep.”

Hugh grunted as he heard the bed creak in the other room. Then he thumped his pillow and settled down again.

“Just the same,” he murmured, “it’s piffling poppycock! That’s just what it is, piffling poppycock!”