CHAPTER IV

“I’M ORDWAY”

Bert, for one, found himself at a loose end the next morning. He lingered as long as possible over breakfast, but the day promised to be even hotter than the one before, and his appetite was soon satisfied. He and Nick sat for a while in the shade of the trees near the middle gate, but the heat soon drove them indoors, and Bert climbed up to Number 29 and unenthusiastically wrenched the lid from the packing case there and set about the distribution of the contents. The few pictures were deposited against a wall, since it was best to see what his roommate was bringing before deciding as to the disposition of them. His books he found place for and he laid some extra clothing in the dresser drawers in the bedroom on the right. He had selected that room in preference to the one on the other side since Lothrop stood at right angles to the other buildings in the row and from “29b” one had an uninterrupted view along the fronts of Trow, School and Manning. Only the gymnasium, hiding behind the shoulder of the last dormitory, was out of sight. From the other bedroom, “29a,” much of this view was cut off by a corner of Trow, and Bert acted on the basis of “first come, first served.”

The study was a good-sized square room, lighted by two windows set in a dormer, beneath which was a wide and comfortable seat. A bright-hued rug occupied the center of the floor and the walls were papered attractively to the height of the picture molding in tones of golden-brown. Above the molding was a foot of white plaster, and two plastered beams ran the length of the ceiling. The furniture was of brown mission; two study desks, a table in the center of the room, a Morris chair upholstered in brown leather beside it, two armchairs, two sidechairs, and a settle. The desks were supplied with green-shaded droplights.

The bedrooms were identical. Each had a single dormer window. Blue two-tone paper covered the walls and a rug flanked the single white iron bed. A dresser, a washstand and a chair completed the furnishings. There was generous closet room.

Bert was glad when Nick came in at eleven and gave him an excuse for stopping his half-hearted labors. Nick was down to a pair of soiled flannel trousers, supported by a most disreputable leather strap that scarcely deserved the name of belt, a white tennis shirt, open at the throat, and a pair of brown canvas “sneakers.” And he looked as though he thought he still had far too much on as he stretched himself out on the window-seat, sprawled one foot over the edge, and hung the other across the sill.

“Four or five fellows came a while ago,” he announced. “Leddy and Ayer and some others. Hairwig, too. Hairwig looks like he’d been sitting in the sun all summer. Tanned to beat the band.”

Hairwig’s real name was Helwig, and he was instructor in physics and chemistry. Being a German, the boys had at first called him Herr Helwig, and later had shortened it to Hairwig. The news of his advent didn’t, however, greatly interest Bert, who inquired:

“Any of our masters shown up?”

“Haven’t seen any. I told you, didn’t I, that I ran across Smiles in New York one day? He was all dolled up. Said he was going out west somewhere to teach at a summer school. He seemed real glad to see me, too. Smiles is a good old sport.”

“He isn’t old.”

“N-no, but Latin instructors always seem old. They know so plaguey much! Who do you think will be proctor up here this year?”

“Cathcart, I suppose. He’s the only senior on the floor. Wonder if we’re going to have a big junior class.”

“Whopping, I heard; eighty-something. Know anyone coming up?”

Bert shook his head. “No, and I’m glad I don’t. You always have to look after them, and they’re nuisances.”

“You’ll have to do the guide and mentor act for your friend Ordway,” reminded Nick, with a malicious grin. “Did you say he was an upper middler?”

“Yes.”

“I’d hate to enter a school in the middle like that,” reflected Nick. “I should think it would be hard.”

“I don’t see why.”

“Well, you don’t know anyone, in the first place. It would take most of the year to get acquainted, and then you’d only have one year left. Going to put him up for Lit?”

“I suppose so, if he wants me to. You have to do that much for a roommate, I guess.”

“When’s he coming?”

“Don’t know and don’t care. Want to buy a good racket?”

“How much?”

“Dollar and a half.”

Nick accepted the proffered article and viewed it dubiously.

“I’d have to have it restrung.”

“Why would you? There’s only one string gone. Take it along and try it.”

“Give you a dollar.”

“I guess you would! It cost seven. Hand it over here, you Shylock.”

“Dollar and a quarter, then.”

“Cash?”

“Dollar down and the balance——”

“Some time?”

“No, next month; honest.”

“All right, but you’re getting it dirt cheap. Where’s the dollar?”

“Downstairs. You don’t think I carry all that money around with me, do you?”

“All right, but we’ll stop in for it before you forget it. Are you really going over to the Junction to meet Guy?”

“Surest thing you know! Want to come along?”

“I wouldn’t make the trip on that hot, dusty old train for a thousand dollars!”

“You ought to, though. You ought to go over and meet your new chum.”

Bert grunted. “I’m likely to! I’ve been wondering if he will bring any pictures and truck like that. I hope, if he does, he won’t have the usual rot. This is too good a study to fill up with chromos. Something tells me, Nick, that I’m an awful idiot to go in with some fellow I’ve never seen. Bet you anything he will be a fresh kid.”

Nick chuckled. “I decline the wager, Bert. Also, I agree with you that you’re taking a chance. Still, you can’t tell. Where does he come from?”

“Somewhere in Maryland.”

“Baltimore? I knew a fellow who lived in Baltimore, and he was a crackajack.”

“No, some place I never heard of. I forget it now. I suppose that makes him a Southerner, doesn’t it?”

“Of course. Anything against Southerners?”

“No, only they’re a bit stuck up. If he tries it with me I’ll shut him up mighty quick!”

“Bert, your disposition is entirely ruined. I guess it’s the weather. I’m glad I’m not What’s-his-name, Ordway.”

“If you’d had the decency to come in with me——”

“Don’t blame me, old scout. Write to dad about it. I wanted to, all right. Put something on and let’s do something.”

“What is there to do?”

“I’ll play you a set of tennis. It won’t be bad if we take it easily.”

“Tennis! I see myself racing around a court a day like this! How hot is it, anyway?”

“About two hundred in the shade. Then why stay in the shade? Say, Bert, what sort of a captain is Ted going to make?”

“Good.”

“I wonder!”

“Don’t see why not. He’s popular, and he’s a good player——”

“Yes, but he isn’t awfully—oh, you know what I mean; he isn’t exactly brilliant, eh?”

“He doesn’t need to be. Bonner will look after that part of it.”

“Well, I never saw any sparks flying from Bonner, for that matter,” returned Nick dryly.

“What’s the good of being brilliant, as you call it? In football, I mean. It’s knowledge of the game that does the business. And Bonner certainly knows football; and so does Ted.”

“Yes, that’s so. All right. We’ll hope for the best. Come on down and I’ll find that old dollar. Then we’ll go over and see Leddy. He’s probably trying to unpack, and he oughtn’t to do it in this weather.”

They managed to kill time until luncheon was served in Manning, and after that they joined a crowd in the common room there and remained until it was time for Nick to go to the station to take the train for Needham Junction. Mr. Russell, Greek instructor, having arrived, Bert went over to Trow to consult him about his new work. Greek had been hard sledding for Bert the year before and he viewed the first four books of Hellenica with misgiving. The consultation in the master’s study in Trow took up the better part of a half hour, for “J. P.,” as Mr. Russell was called, was not to be hurried. When he finally got away Bert climbed up to Pop Driver’s room on the floor above and found Ted Trafford and Roy Dresser in possession. Roy was Pop’s roommate. Pop, he explained, had gone to the village to buy some lemons. They had drawn lots and Pop had lost. If he didn’t die of sunstroke before he got back there was going to be a lemonade of magnificence. Bert decided to wait around.

But Pop tarried and after awhile Ted discovered that it was after four o’clock and hurried out. They could hear him taking the stairs three at a time. Bert abandoned hope of that lemonade and followed Ted, Roy Dresser apologizing for Pop and adding that if Bert would keep his ears open he, Roy, would yell across when the lemons arrived.

It seemed a trifle cooler in the campus and the shadow of Lothrop stretched far along the red brick walk that ran, the main artery of travel, along the fronts of the buildings. A locomotive shrieked despairingly a mile or so away and Bert knew that the first of the two trains on which the bulk of the returning students would arrive was nearing the station. Again his thoughts reverted to Ordway and again he wondered pessimistically what sort of a youth fate was going to impose upon him. Ordway might not come until six-thirty, however; many fellows didn’t; and Bert rather hoped he would be of their number. He was disposed to postpone the inevitable.

The rooms in Lothrop had been thrown open, doors and windows alike, and the corridors were far cooler than they had been since he had taken possession of Number 29. Quite a draft of air was blowing down the staircase well. In the study, he put away the last few belongings, placed the packing-case outside for removal to the store-room, and finally, lowering the shades at the windows through which the afternoon sun was shining hotly, took up his schedule and, stretching himself on the window-seat, studied it dubiously. Mathematics 4, Greek 3, English 4, French 1, History 3a; eighteen hours altogether, aside from Physical Training. From the latter, however, he was exempt so long as he was in training with the football team. Eighteen hours was the least required for the third year, and he was expected to select another study. He mentally pondered the respective merits of physics and chemistry. Physics was known as a “snap course,” but Bert was in favor of leaving it for his senior year. The same with chemistry. He rather leaned toward German, but Mr. Teschner, or “Jules,” as he was usually called, was a hard taskmaster and his classes were not viewed with much enthusiasm. Still, unless he took physics or chemistry it would have to be German, and after a few minutes of cogitation he wrote German 1 on the card in his hand. The schedule had yet to be approved and he wondered whether he would be allowed to go in so heavily for languages. The schedule was a bit top-heavy in that way, with thirteen hours of the twenty-one given to Greek, German, and French. Probably they would make him substitute physics for German. He slipped the card in his pocket, with a sigh for the vexations of life, and became aware that Lothrop Hall was at last inhabited. Steps scuffed on the stairs, voices sounded, bags and trunks thumped. The invasion had begun in earnest. Half inclined to go down and see if Guy Murtha had arrived, he nevertheless found himself too lazy to stir and so when, a few moments later, footsteps drew near the open door he was still sprawled on his back.

“This must be it, Bowles,” said a voice. “Yes, twenty-nine. Oh, I beg your pardon!”

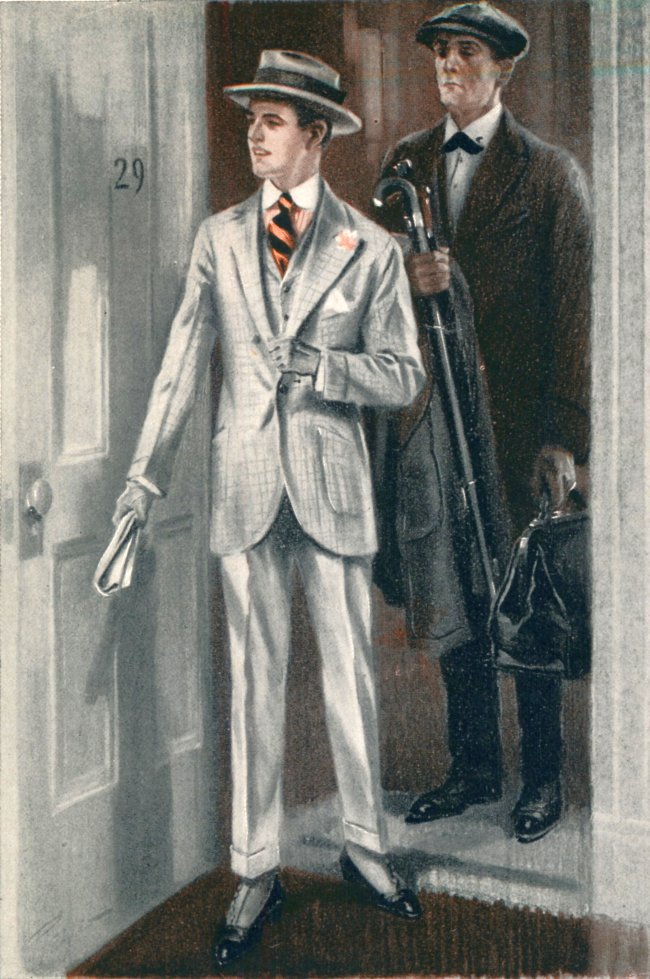

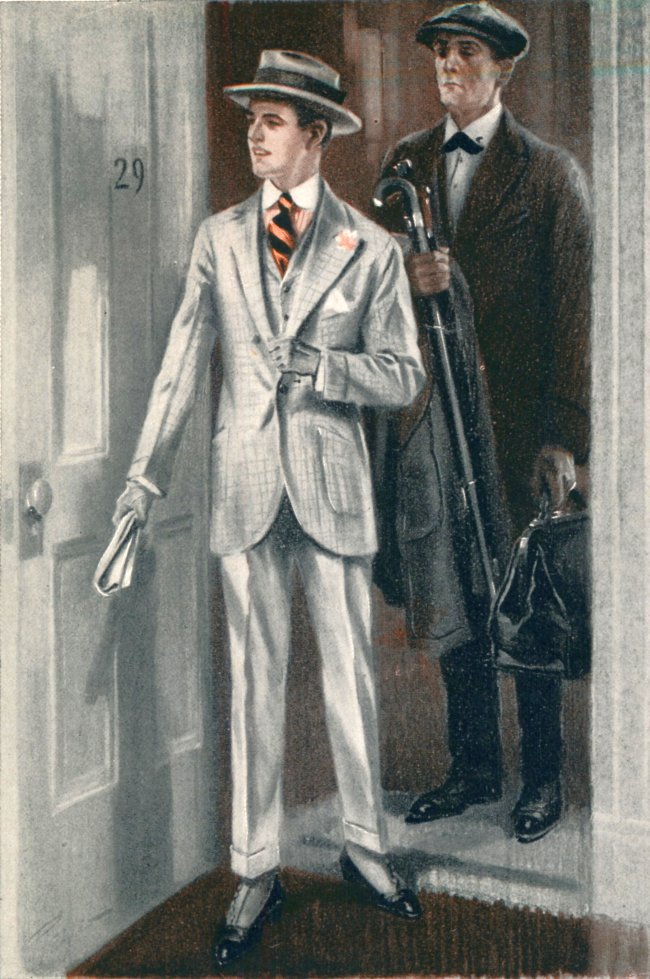

Bert sat up and slid his feet to the floor. In the doorway stood a slim, pleasant-faced youth, and behind him a very serious-looking man held an extremely large kit-bag, an umbrella, and a folded gray overcoat. The youth advanced toward Bert, smiling and removing a gray glove.

“I fancy you are Winslow,” he said. “I’m Ordway. I believe we share these quarters, eh?”

“‘I’m Ordway.’”

Bert shook hands. “Glad to know you,” he replied. “Beastly hot, isn’t it? That’s your room over there.” He glanced inquiringly at the second arrival who, still holding his burdens, had paused just inside the door. But if he looked for an introduction none was forthcoming. Ordway, who had now removed both gloves and tossed them nonchalantly to the table, evidently had no thought of making his companion known.

“Ripping view from here,” he said, glancing from the window. Then, turning: “In there, Bowles,” he directed, and nodded toward the open door of the bedroom. “Just dump them, will you? I’ll look after them myself.”

Bag and coat and umbrella disappeared, Bert’s gaze following their bearer curiously. Ordway had thrust his hands in his pockets and was leisurely examining the study. His manner was a queer mixture of quiet assurance and diffidence. When he had shaken hands he had reddened perceptibly, but now he was looking the place over just as though, as Bert silently told himself, he had ordered the whole thing. “I like this,” he said, after a moment. “Rather jolly, isn’t it?”

Bert was spared a reply, for just then the mysterious Bowles appeared in the bedroom doorway. “Shan’t I unpack the bag, sir?” he asked.

“No, never mind it, thanks.” Ordway consulted a watch. “I fancy you’d better beat it, Bowles. Your train leaves in fifteen minutes, you know.”

“Yes, sir, but there’s another one, sir, a bit later.”

“Are you sure of that?” Ordway glanced inquiringly at Bert. “He’s wrong, eh?”

“Yes, the next one doesn’t go until seven-five. If he wants to get this one he will have to hustle. It’s a good ten minutes’ walk to the station.”

“Thanks. This gentleman’s right, Bowles. You’d better start along. You know your way, eh? Tell mother I’m quite all right; everything’s very jolly.” The boy walked to the door with the man and pulled a leather purse from his pocket. “Better treat yourself to a bit of a jinks when you get to town. You’ll have four hours to wait, you know. Good-by, Bowles.”

“Thank you, Master Hugh. Good-by, sir. I hung the coat in the closet, sir, and the keys are on the dresser.”

“Right, Bowles. Now beat it or you’ll miss that train. Good-by.”

Ordway sauntered back to the study, smiling. “Bowles always gets time-tables twisted,” he chuckled. “Rum chap that way. Bet you anything you like he will miss that train.”

“He’s got twelve minutes,” said Bert. “Is he a—a servant?”

“Bowles? Yes, he’s been looking after me ever since I was out of the nursery. He’s a little bit of all right, Bowles.” Ordway seated himself on the farther end of the seat, looked interestedly about the campus, no longer silent and empty, and finally turned his gaze to Bert. Again the color crept into his cheeks and he said diffidently, almost stammeringly:

“I say, Winslow, I hope you’re going to like me, you know.”