CHAPTER II

UNDER QUEEN MARY

When the Parliament which did these great things was over, the newly-established Kirk began to labour at its own development, supplying as far as was possible ministers to the more important centres. There were but thirteen available in all according to the lists of those appointed to independent charges: and though they no doubt were supplemented by various of the laymen who had already been authorised to read prayers and preach in the absence of other qualified persons—one of whom, Erskine of Dun, became one of the superintendents of the new organisation—the clerical element must have been very small in comparison with the number of the faithful and the power and influence accorded to the preachers. When these indispensable arrangements had been made the chiefs of the Reformers began to draw up the Book of Discipline,—a compendium of the Constitution of the Church establishing her internal order, the provisions to be made for her, her powers in dealing with the people in general, and special sinners in particular,—as the Confession of Faith was of her doctrines and belief. But this was a much harder morsel for the lords to swallow. Many a stout spirit of the Congregation had held manfully for the Reformed faith and escaped with delight from the exactions and corruptions of the Romish clergy who yet had not schooled his mind to give up the half of his living, the fat commendatorship or priory which had been obtained for him by the highest influence, and upon which he had calculated as a lawful provision for himself and his family. One would have supposed that the meddling and keen supervision of every act of life, which was involved in the Church's stern claim of discipline, would also have alarmed and revolted a body of men not all conformed to the purest models of morality. But this seems to have troubled them little in comparison with the necessity of giving up their share of Church lands and ecclesiastical wealth generally, in order to provide for the preachers, and the needs of education and charity. "Everything that repugned to their corrupt affections was termed in their mockage 'devout imaginations,'" says Knox: and it was no doubt Lethington from whose quiver this winged word came, with so many more.

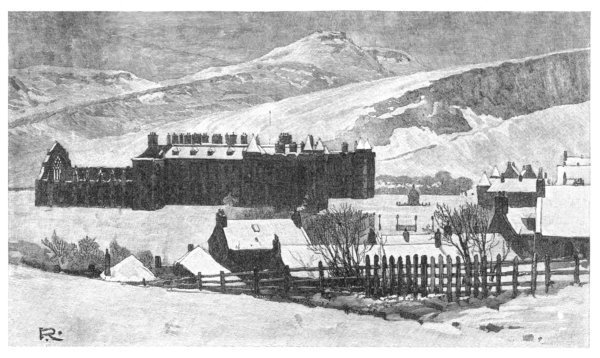

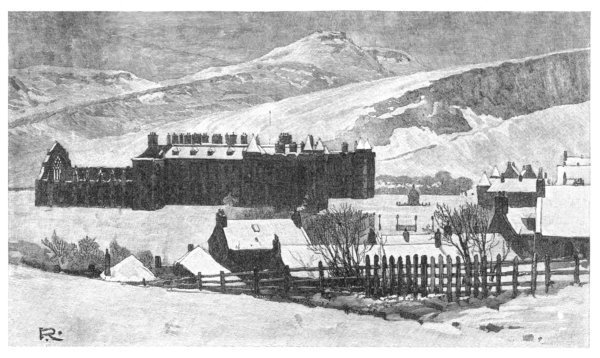

HOLYROOD PALACE AND ARTHUR'S SEAT

A number of the lords, however, subscribed to the Book of Discipline though with reluctance, but some, and among them several of the most staunch supporters of the Reformation, held back. Knox had himself been placed in an independent position by his congregation, the citizens of Edinburgh, and he was therefore more free to press stipulations which in no way could be supposed to be for his own interest: but he evidently had not taken into account the strong human disposition to keep what has been acquired and the extreme practical difficulty of persuading men to a sacrifice of property. In other matters too there were drawbacks not sufficiently realised. There can be no grander ideal than that of a theocracy, a commonwealth entirely ruled and guided by sacred law: but when it is brought to practice even by the most enlightened, and men's lives are subjected to the keen inspection of an ecclesiastical board new to its functions, and eager for perfection, which does not disdain the most minute detail, nor to listen to the wildest rumours, the high ideal is apt to fall into the most intolerable petty tyranny. And notwithstanding the high exaltation of many minds, and the wonderful intellectual and emotional force which was expended every day in that pulpit of St. Giles's, swaying as with great blasts and currents of religious feeling the minds of the great congregation that filled the aisles of the cathedral, it is to be doubted whether Edinburgh was a very agreeable habitation in those days of early fervour, when the Congregation occupied the chief place everywhere, and men's thoughts were not as yet distracted by the coming of the Queen. During this period there occurs a curious and most significant story of an Edinburgh mob and riot, which might be placed by the side of the famous Porteous mob of later days, and which throws a somewhat lurid light upon the record of this most triumphant moment of the early Reformation. The Papists and bishops, Knox says, had stirred up the rasckall multitude to "make a Robin Hood." We may remark that he never changes his name for the mob, of which he is always sternly contemptuous. When it destroys convents and altars he flatters it (though he acknowledges sometimes a certain ease in finding the matter thus settled for him) with no better a title. He was no democrat though the most independent of citizens. The vulgar crowd had at no time any attraction for him.

It seems no very great offence to "make a Robin Hood": but it is evident this popular festival had been always an occasion of rioting and disorderly behaviour since it was condemned by various acts of previous Parliaments. It will strike the reader, however, with dismay and horror to find that one of the ringleaders having been taken, he was condemned to be hanged, and a gibbet erected near the Cross to carry this sentence into execution. The Diurnal of Occurrents gives by far the fullest and most graphic account of what followed. The trades rose in anxious tumult, at once angry and terrified.

"The craftsmen made great solicitations at the hands of the provost, John Knox minister, and the baillie, to have gotten him relieved, promising that he would do anything possible to be done saving his life—who would do nothing but have him hanged. And when the time of the poor man's hanging approached, and that the poor man was come to the gibbet with the ladder upon which the said cordwainer should have been hanged, the craftsman's children (apprentices?) and servants past to armour; and first they housed Alexander Guthrie and the provost and baillies in the said Alexander's writing booth, and syne come down again to the Cross, and dang down the gibbet and brake it in pieces, and thereafter past to the tolbooth which was then steekit: and when they could not apprehend the keys thereof they brought hammers and dang up the said tolbooth door perforce, the provost, baillies, and others looking thereupon; and when the said door was broken up ane part of them passed in the same, and not only brought the said condemned cordwainer forth of the said tolbooth, but also all the remaining persons being thereintill: and this done they passed up the Hie gate, to have past forth at the Nether Bow."

The shutting up of the provost and bailie in the "writing booth"—one of the wooden structures, no doubt, which hung about St. Giles's, as round so many other cathedrals, where a crowd of little industries were collected about the skirts of the great church, the universal centre of life—has something grimly comic in it, worthy of an Edinburgh mob. Guthrie's booth must have been at the west end, facing the Tolbooth, and the impotence of the authorities, thus compelled to look on while the apprentices and young men in their leather aprons, armed with the long spears which were kept ready in all the shops for immediate use, broke down the prison doors with their hammers and let the prisoners go free—must have added a delightful zest to the triumph of the rebels, who had so lately pleaded humbly before them for the victim's life, but in vain. The provost was Archibald Douglas of Kilspindie, a name little suitable for such a dilemma. When the rude mob, with their shouts and cries, had turned their backs, the imprisoned authorities were able to break out and take shelter in the empty Tolbooth; but when the crowd surged up again, finding the gates closed at the Nether Bow, into the High Street, a scuffle arose, a new "Clear the Causeway," though the defenders of order kept within the walls of the Tolbooth, and thence shot at the rioters, who returned their fire with hagbuts and stones—from three in the afternoon till eight o'clock in the evening, "and never ane man of the town stirred to defend their provost and baillies." Finally the Constable of the Castle was sent for, who made peace, the craftsmen only laying down their arms on condition not only of absolute immunity from punishment for the day's doings, but with an undertaking that all previous actions against them should be stopped, and their masters made to receive them again without grudge or punishment—clearly a complete victory for the rioters. This extorted guarantee was proclaimed at the Cross at nine o'clock on the lingering July night, in the soft twilight which departs so unwillingly from northern skies; and a curious scene it must have been, with the magistrates still cooped up behind the barred windows of the Tolbooth, the triumph of the mob filling the streets with uproar, and spectators no doubt at all the windows, story upon story, looking on, glad, can we doubt? of something to see which was riot without being bloodshed. John Knox adds an explanation of his conduct in his narrative of the occurrence, which somewhat softens our feeling towards him. He refused to ask for the life of the unlucky reveller not without a reason, such as it was.

"Who did answer that he had so oft solicited in their favour that his own conscience accused him that they used his labours for no other end but to be a patron to their impiety. For he had before made intercession for William Harlow, James Fussell, and others that were convict of the former tumult. They proudly said 'that if it was not stayed both he and the Baillies should repent it.' Whereto he answered 'He would not hurt his conscience for any fear of man.'"

It was not perhaps the fault of Knox or his influence that a man should be sentenced to be hanged for the rough horseplay of a Robin Hood performance, or because he was "Lord of Inobedience" or "Abbot of Unreason," like Adam Woodcock; but the extraordinary exaggeration of a society which could think such a punishment reasonable is very curious.

Equally curious is the incidental description of how "the Papists" crowded into Edinburgh after this, apparently swaggering about the streets, "and began to brag as that they would have defaced the Protestants." When the Reformers perceived the audacity of their opponents, they replied by a similar demonstration: "the brethren assembled together and went in such companies, and that in peaceable manner, that the Bishops and their bands forsook the causeway." Many a strange sight must the spectators at the high windows, the old women at their "stairheads," from which they inspected everything, have seen—the bishops one day, the ministers another, and John Knox, were it shade or shine, crossing the High Street with his staff every day to St. Giles's, and seeing everything, whatever occurred on either side of him, with those keen eyes.

This tumult, however, was almost the end of the undisturbed reign of the Congregation. In August, Mary Stewart, with all the pomp that her poor country could muster for her, arrived in a fog, as so many lesser people have done, on her native shores; and henceforward the balance of power was strangely disturbed. The gravest of the lords owned a certain divergence from the hitherto unbroken claims of religious duty, and a hundred softnesses and forbearances stole in, which were far from being according to the Reformer's views. The new reign began with a startling test of loyalty to conviction, which apparently had not been anticipated, and which came with a shock upon the feelings even of those who loved the Queen most. The first Sunday which Mary spent in Holyrood, preparations were made for mass in the chapel, probably with no foresight of the effect likely to be produced. Upon this a sudden tumult arose in the very ante-chambers. "Shall that idol be suffered again to take its place in this realm? It shall not," even the courtiers said to each other. The Master of Lindsay, that grim Lindsay of the Byres, so well known among Mary's adversaries, standing with some gentlemen of Fife in the courtyard, declared that "the idolatrous priests should die the death." In this situation of danger the Lord James, afterwards so well known as Murray, the Queen's brother, put himself in the breach. He "took upon him to keep the door of the chapel." There was no man in Scotland more true to the faith, and none more esteemed in the Congregation. He excused himself after for this act of true charity by saying that his object was to prevent any Scot from entering while the mass was proceeding: but Knox divined that it was to protect the priest, and preserve silence and sanctity for the service, though he disapproved it, that Murray thus intervened. The Reformers did not appreciate the good brother's devotion. Knox declared that he was more afraid of one mass than of ten thousand armed men, and the arches of St. Giles's rang with his alarm, his denunciation, his solemn warning. He recounts, however, how by degrees this feeling softened among those who frequented the Court. "There were Protestants found," he says, "that were not ashamed at tables and other open places to ask 'Why may not the Queen have her mass, and the form of her religion? What can that hurt us, or our religion?' until by degrees this indulgence rose to a warmer and stronger sentiment. 'The Queen's mass and her priests will we maintain: this hand and this rapier shall fight in their defence.'" One can well imagine the chivalrous youth or even the grave baron, with generous blood in his veins, who, with hand upon the hilt of the too ready sword, would dare even Knox's frown with this outcry; and in these days it is the champion of the Queen and of her conscience who secures our sympathy. But the Reformer had at least the cruel force of logic on his side, the severe logic which decreed the St. Bartholomew. To stamp out the previous faith was the only policy on either side.

Then, as now, we think, there are few even of those who are forced to believe that the after-accusations against Queen Mary were but too clearly proved, who will not look back with a compunctious tenderness upon that early and bright beginning of her career. So strong a sense of remorseful pity, and the intolerableness of such a fate, overcomes the spectator, that he who stands by and looks on, knowing all that is coming, can scarcely help feeling that even he, unborn, might send a shout from out the dim futurity to warn her. She came with so much hope, so eagerly, to her new kingdom, so full of pleasure and interest and readiness to hear and see, and to be pleased with everything—even John Knox, that pestilent preacher, of whom she must have heard so much; he who had written the book against women which naturally made every woman indignant yet curious, keenly desirous to see him, to question him, to put him on his defence. I think great injustice has been done to both in the repeated interviews in which the sentimentalist perceives nothing but a harsh priest upbraiding a lovely woman and making her weep; and the sage of sterner mettle sees an almost sublime sight, a prophet unmoved by the meretricious charms of a queen of hearts. Neither of these exaggerated views will survive, we believe, a simple reading of the interviews themselves, especially in Knox's account of them. He is not merciless nor Mary silly. One would almost fancy that she liked the encounter which matched her own quick wit against the tremendous old man with his "blast against women," his deep-set fiery eyes, his sovereign power to move and influence the people. He was absolutely a novel personage to Mary: their conversations are like a quick glancing of polished weapons—his, too heavy for her young brilliancy of speech and nature, crushing with ponderous force the light-flashing darts of question; but she, no way daunted, comprehending him, meeting full in the face the prodigious thrust. A brave young creature of twenty confronting the great Reformer, in single combat so to speak, and retiring from the field, not triumphant indeed, but with all the honours of war, and a blessing half extorted from him at the end, she secures a sympathy which the weaker in such a fight does not always obtain, but which we cannot deny to her in her bright intelligence and brave defence of her faith. When his friends asked him, after this first interview, what he thought of the Queen, he gave her credit for "a proud mind, a crafty wit, and an indurate heart." But curiously enough, though the effect is not unprecedented, the faithfulness of genius baulks the prejudices of the writer, and there is nowhere a brighter or more genial representation of Mary than that which is to be found in a history full of abuse of her and vehement vituperation. She is "mischievous Marie," a vile woman, a shameless deceiver; every bad name that can be coined by a mediæval fancy, not unlearned in such violences; but when he is face to face with this woman of sin it is not in Knox to give other than a true picture, and that—apart from the grudging acknowledgment of her qualities and indication of evil intentions divined—is almost always an attractive one.

He, too, shows far from badly in the encounter. In this case, as in so many others, the simple record denuded of all gloss gives at once a much better and we do not doubt much more true representation of the two remarkable persons involved, than when loaded with explanations, either from other people or from themselves. It cannot be said that Knox is just to Mary in the opinions he expresses of her, as he is in the involuntary picture which his inalienable truthfulness to fact forces from him. It must be remembered, however, that his history was written after the disastrous story had advanced nearly to its end, and when the stamp of crime (as Knox and so many more believed) had thrown a sinister shade upon all her previous life. Looking back upon the preliminaries which led to such wild confusion and misery, it was not unnatural that a man so absolute in judgment should perceive in the most innocent bygone details indications of depravity. It is one (whether good or bad we will not say) consequence of the use and practice of what may, to use a modern word, be called society, that men are less disposed to believe in the existence of monstrous and hideous evil, that they do not attach an undue importance to trifles nor take levity for vice. Knox had all the limitations of mind natural to his humble origin, and his profession, and the special disadvantage which must attach to the habit of investigating by means of popular accusation and gossip, problematical cases of immorality. He was able to believe that the Queen, when retired into her private apartments with her ladies, indulged in "skipping not very comelie for honest women," and that all kinds of brutal orgies went on at court—incidents certainly unnecessary to prove her after-guilt, and entirely out of keeping with all the surrounding associations, as if Holyrood had been a changehouse in "Christ Kirk on the green." It did not offend his sense of the probable or likely that such insinuations should be made, and he recorded them accordingly not as insinuations but as facts, in a manner only possible to that conjoint force of ignorance and scorn which continually makes people of one class misconceive and condemn those of another. Dancing was in those days the most decorous of performances: but if Mary had been proved to have danced a stately pas seul in a minuet, it was to Knox, who knew no better, as if she had indulged in the wildest bobbing of a country fair—nay, he would probably have thought the high-skipping rural performer by far the more innocent of the two.

This is but an instance of many similar misconceptions with which the colour of the picture is heightened. An impassioned spectator looking on with a foregone conclusion in his mind, never apparently able to convince himself that vice does not always wear her trappings, but is probably much more dangerous when she observes the ordinary modesties of outward life, is always apt to be misled in this way. The state of affairs in which a great body of public men, not only ministers, but noble men and worthy persons of every degree, could personally address the Queen, and that almost in the form of an accusation couched in the most vehement terms, because of a libertine raid made by a few young gallants in the night, on a house supposed to be inhabited by a woman of damaged character, is inconceivable to us—a certain parochial character, a pettiness as of a village, thus comes into the great national struggle. The Queen's uncle, who had accompanied her to Scotland, was one of the young men concerned, along with Earl Bothwell and another. "The horror of this fact and the raretie of it commoved all godlie hearts," said Knox—and yet there was no lack of scandals in that age notwithstanding the zeal of purification. When the courtiers, alarmed by this commination (in which every kind of spiritual vengeance upon the realm and its rulers was denounced), asked, "Who durst avow it?" the grim Lindsay replied, "A thousand gentlemen within Edinburgh." Yet if Edinburgh was free from disorders of this kind, it was certainly far from free of other contentions. The proclamations from the Cross during Mary's brief reign give us the impression of being almost ceaseless. The Queen's Majestie proclaimed by the heralds now one decree, now another, with a crowd hastily forming to every blast of the trumpet: and the little procession in their tabards, carrying a moving patch of bright colour and shining ornament up all the long picturesque line of street, both without and within the city gates, was of almost daily occurrence. It was some compensation at least for the evils of an uncertain rule to have that delightful pageant going on for ever. Sometimes there would arise a protest, and one of the lords, all splendid in his jewelled bonnet, would step forward to the Lord Lyon and "take instruments and crave extracts," according to the time-honoured jargon of law; while from his corner window perhaps John Knox looked out, his eager pen already drawn to answer, the tumultuous impassioned sentences rushing to his lips.

When it was found that no punishment was to follow that "enormitie and fearful attemptal," but that "nightly masking" and riotous behaviour continued, some of the lords took the matter in their own hands, and a great band known as "my Lord Duke his friends" took the causeway to keep order in the town. When the news was brought to Earl Bothwell that the Hamiltons were "upon the gait," there were vows made on his side that "the Hamiltons should be driven not only out of the town but out of the country." The result, however, of this sudden surging up of personal feud to strengthen the bitterness of the quarrel between licence and repression, was that the final authorities were roused to make the fray an affair of State; and Murray and Huntly were sent from the abbey with their companies to stop the impending struggle. These sudden night tumults, the din of the struggle and clashing of the swords, the gleaming torches of the force who came to keep order, were sights very familiar to Edinburgh. But this fray brings upon us, prominent in the midst of the nightly brawls, the dark and ominous figure whose trace in history is so black, so brief, and so disastrous—once only had he appeared clearly before, when he intercepted in the interest of the Queen Regent the money sent from England to the Congregation. Now it is in a very different guise. Bothwell, as probably the ringleader in the disorders of the young nobles, was apparently the only person punished. He was confined to his own lodging, and it was apparently at this time that he sought the intervention of Knox, who seems to have been the universal referee. Knox gladly granted his prayer for an interview, which was brought him by a citizen of Edinburgh, with whom the riotous Earl had dealings. No doubt the Reformer expected a new convert; and indeed Bothwell had his preliminary shrift to make, and confessed his repentance of his previous action against the Congregation, which he said was done "by the entysements of the Queen Regent." But the Earl's object was not entirely of this pious kind. He informed Knox that he had offended the Earl of Arran, and that he was most anxious to recover that gentleman's favour, on the ground, apparently, that a feud with so great a personage compelled him to maintain a great retinue, "a number of wicked and unprofitable men, to the utter destruction of my living."

Knox received with unusual favour this petition for his intervention, and for (to the reader) an unexpected reason: "Albeit to this hour," he said, "it hath not chanced me to speak to your lordship face to face, yet have I borne a good mind to your honour, and have been sorry in my heart of the troubles that I have heard you to be involved in. For, my lord, my grandfather, goodsire and father, have served your lordship's predecessors, and some of them have died under their standards; and this is part of the obligation of our Scottish kindness." He goes on naturally to exhort his visitor to complete repentance and "perfyte reconciliation with God;" but ends by promising his good offices for the wished-for reconciliation with man. In this mediation Knox was successful: and as the extraordinary chance would have it, it was at the Kirk of Field, doomed to such dismal association for ever with Bothwell's name, that the meeting with Arran, under the auspices of Knox—strange conjunction!—took place, and friendship was made between the two enemies. Knox made them a little oration as they embraced each other, exhorting them to "study that amitie may ensure all former offences being forgotten."

This is strange enough when one remembers the terrible tragedy which was soon to burst these walls asunder; but stranger still was to follow. The two adversaries thus reconciled came to the sermon together next day, and there was much rejoicing over the new penitent. But four days after, Arran, with a distracted countenance, followed Knox home after the preaching, and calling out "I am treacherously betrayed," burst into tears. He then narrated with many expressions of horror the cause of his distress. Bothwell had made a proposal to him to carry off the Queen and place her in Dunkeld Castle in Arran's hands (who was known to be half distraught with love of Mary), and to kill Murray, Lethington, and the others that now misguided her, so that he and Arran should rule alone. The agitation of the unfortunate young man, his wild looks, his conviction that he was himself ruined and shamed for ever, seem to have enlightened Knox at once as to the state of his mind. Arran sent letters all over the country—to his father, to the Queen, to Murray—repeating this strange tale, but soon betrayed by the endless delusions which took possession of him that his mind was entirely disordered. The story remains one of those historical puzzles which it is impossible to solve. Was there truth in it—a premature betrayal of the scheme which afterwards made Bothwell infamous? did this wild suggestion drive Arran's mind, never too strong, off the balance? or was it some strange insight of madness into the other's dark spirit? These are questions which no one will ever be able to answer. It seems to have caused much perturbation in the Court and its surroundings for the moment, but is not, strangely enough, ever referred to when events quicken and Bothwell shows himself as he was in the madman's dream.

The chief practical question on which Knox's mind and his vigorous pen were engaged during this early period of Mary's reign was the all-important question to the country and Church of the provision for the maintenance of ministers, for education, and for the poor—the revenues, in short, of the newly-established Church, these three objects being conjoined together as belonging to the spiritual dominion. The proposal made in the Book of Discipline, ratified and confirmed by the subscription of the lords, was that the tithes and other revenues of the old Church, apart from all the tyrannical additions which had ground the poor (the Uppermost Cloth, Corpse present, Pasch offerings, etc.), should be given over to the Congregation for the combined uses above described. This in principle had been conceded, though in practice it was extremely hard to extract those revenues from the strong secular hands into which in many cases they had fallen, and which had not even ceased to exact the Corpse present, etc. The Reformers had strongly urged the necessity of having the Book of Discipline ratified by the Queen on her arrival; but this suggestion had been set aside even by the severest of the lords as out of place for the moment. To such enlightened critics as Lethington the whole book was a devout imagination, a dream of theorists never to be realised. The Church, however, with Knox at her head, was bent upon securing this indispensable provision, though it may well be supposed that now, with not only the commendators and pensioners but the bishops themselves and other ecclesiastical functionaries, inspirited and encouraged by the Queen's favour, and hoping that the good old times might yet come back, it was more difficult than ever to get a hearing for their claim. And great as was the importance of a matter involving the very existence of the new ecclesiastical economy, it was, even in the opinion of the wisest, scarcely so exciting as the mass in the Queen's chapel, against which the ministers preached, and every careful burgher shook his head; although the lords who came within the circle of the Court were greatly troubled, knowing not how to take her religious observances from the Queen, they who had just at the cost of years of conflict gained freedom for their own. On one occasion when a party of those who had so toiled and struggled together during all the troubled past were met in the house of one of the clerk registers, the question was discussed between them whether subjects might interfere to put down the idolatry of their prince—when all the nobles took one side, and John Knox, his colleagues, and a humble official or two were all that stood on the other. As a manner of reconciling the conflicting opinions Knox was commissioned to put the question to the Church of Geneva, and to ask what in the circumstances described the Church there would recommend to be done. But the question was never put, being transferred to Lethington's hands, then back again to those of Knox, perhaps a mere expedient to still an unprofitable discussion rather than a serious proposal.

While these questions were being hotly and angrily discussed on all sides, the preachers and their party growing more and more pertinacious, the lords impatient, angry, chafed and fretted beyond bearing by the ever-recurring question in which they were no doubt conscious, with an additional prick of irritation, that they were abandoning their own side, Mary, still fearing no evil, very conciliatory to all about her, and entirely convinced no doubt of winning the day, went lightly upon her way, hunting, hawking, riding, making long journeys about the kingdom, enjoying a life which, if more sombre and poor outwardly, was far more original, unusual, and diverting than the luxurious life of the French Court under the shadow of a malign and powerful mother-in-law. It did not seem perhaps of great importance to her that the preachers should breathe anathemas against every one who tolerated the mass in her private chapel, or that the lords and their most brilliant spokesman, her secretary Lethington, should threaten to stop the Assemblies of the Church in retaliation. The war of letters, addresses, proclamations, which arose once more between the contending parties