CHAPTER XII.

IT wuz a dretful curiosity to me and a never-failin’ source of interest to watch the ways and habits of the Southern people about Belle Fanchon, both white and colored.

The neighborhood wuzn’t very thickly settled with white people. But still there wuz quite a number of neighbors, and they wuz about all of ’em kind-hearted, generous, hospitable people to their equals.

They seemed to like their own folks the best, the Southern folks; but still they wuz very kind to my son and his wife, and seemed willin’ and glad to neighbor with ’em. While there wuz so much sickness in the house, they seemed anxious to help; and I see that they wuz warm-hearted, ready to take trouble for other folks, ready to give all the help they could.

And they wuz very polite to Josiah Allen and me, and pleasant to talk with. But let the subject of the freedmen come up, or the Freedmen’s Bureau, I could see in a minute that they hated that bureau—hated it like a dog.

I hit aginst that bureau quite a number of times in my talk with them neighbors, and I could see that it creaked awfully in their ears; its draws drawed mighty heavy to ’em, and the hull structure wuz hated by ’em worse than any gulontine wuz ever hated by Imperialists.

And colored schools, of course there wuz exceptions to it, but, as a rule, them neighbors despised the idee of schools for the “niggers,” despised the teachers and the hull runnin’ gear of the institution.

The colored men and wimmen they seemed to look upon about as Josiah and me looked onto our dairy, though mebby not quite so favorably, for there wuz one young yearlin’ heifer and one three-year-old Jersey that I always said knew enough to vote.

They had wonderful minds, both on ’em, so I always said, and I petted ’em a sight and thought everything on ’em.

But the “niggers” in their eyes wuz nuthin’ and never could be anything but slaves; in that capacity they wuz willin’ to do anything for ’em—doctor ’em when they wuz sick, and clothe ’em and take care on ’em.

They wuz willin’ to call ’em Uncle and Aunt and Mammy, but to call ’em Mr. or Mrs. wuz a abomination to ’em; and one woman rebuked me hard for callin’ a old black preacher Mr. Peters.

Sez she, “I wouldn’t think you would call a low-down nigger ‘Mr.’”

But I sez, “I heard you call him Uncle, and that is goin’ ahead of me; for much as I respect him for his good, Christian qualities, I wouldn’t go so fur as to tell a wrong story in order to claim relationship with him. He hain’t no kin to me, and so I am more distant to him and call him Mister.”

But Mrs. Stanwood (that wuz her name) tosted her head, and I see my deep, powerful argument hadn’t convinced her.

And most imegiatly after she begun to run down the white teachers in the colored schools and run the idee of their puttin’ themselves down on a equality with niggers and bein’ so intimate with ’em.

“But,” sez I, “you have told me that your little girl always sleeps with her colored nurse, and you did with yours when you wuz a child. And, ’sez I, “that seems to me about as intimate as anybody can get, to sleep in the same bed; and when both are a layin’ down, they seem to be pretty much on a equality—that is,” sez I, reasonable, “if their pillers are of the same height and bigness.”

And I resoomed—“I never hearn of any white teacher bein’ in that state of equality with the colored people,” sez I; “they are a laborin’ for their souls and minds mostly, and you can’t seem to get on such intimate terms with them, if you try, as you can with bodies.”

Miss Stanwood tosted her head fearful high at this, and didn’t seem impressed by the depth and solidity of my argument no more than if it had been a whiff of wind from a alkelie desert. It wuz offensive to her. And she never seemed to care about conversin’ with me on them topics agin.

But I wuz dretful polite to her, and shouldn’t have said this if she hadn’t opened the subject.

But from all my observations, I see the Southerners felt pretty much alike on this subject, they wuz about unanimous on it—though, as there always must be everywhere, there wuz a few that thought different.

There must be a little salt scattered everywhere, else how could the old earth get salted?

But I couldn’t bear to hear too much skairful talk from Southerners about the two races bein’ intimate with each other. I couldn’t bear to hear too many forebodin’s on the subject, for I know and everybody knows that ever sence slavery existed the two races had been about as intimate with each other as they could be—in some ways; and the white man to blame for it, in most every case.

And I couldn’t seem to think the Bible and the spellin’ book wuz a goin’ to add any dangerous features to the case; no, indeed. I know it wuz goin’ to be exactly the reverse and opposite.

But as interestin’ as the white folks wuz to me to behold and observe down in them Southern States, the colored people themselves wuz still more of a curiosity to me.

To me, who had always lived up North and had never neighbored with anybody darker complexioned than myself (my complexion is good, only some tanned)—it wuz a constant source of interest and instruction to me “to look about and find out,” as the poet has so well remarked.

And I see, as I took my notes, that Victor and Genieve wuz no more to be compared with the rest of the race about them than a eagle and a white dove wuz to be compared with ground birds.

These two seemed to be the very blossoms of the crushed vine of black humanity, pure high blossoms lifted up above the trompled stalks and tendrils of the bruised and bleeding vine that had so long run along the ground all over the South land, for any foot to stamp on, for every bad influence of earth and sky to centre on and debase.

(That hain’t a over and above good metafor; but I’ll let it go, bein’ I am in some of a hurry.)

I spozed then, and I spoze still, that all over the land, wherever this thick, bleeding, tangled undergrowth lingered and suffered, there wuz, anon and even oftener, pure, fair posys lifted up to the sky.

I spozed there wuz hundreds and thousands of bright, intelligent lives reachin’ up out of the darkness into the light, minds jest as bright as the white race could boast, lives jest as pure and consecrated. And I spozed then, and spoze now, that faster and faster as the days go by, and the means of culture and advancement are widening, will these souls be lifted up nigher and nigher to the heavens they aspire to.

A race that has given to the world a Fred Douglass, and that sublime figure of Toussaint L’Ouverture, that form that towers higher than any white saint or hero—and he risin’ to that almost divine height by his own unaided powers, without culture or education—what may it not hope to aspire to, helped by these aids?

Truly the future is glorious with hope and promise for the negro.

But to resoom and continue the epistol I commenced.

The most of the colored people about Belle Fanchon wuz fur different from Victor and Genieve. But a close observer could trace back their faults and weaknesses to their source.

Maggie’s cook wuz a old black woman who wuzn’t over and above neat in her kitchen (it didn’t look much like the kitchen of a certain person whose home wuz in Jonesville—no, indeed), but who got up awful good dinners and suppers and brekfusses.

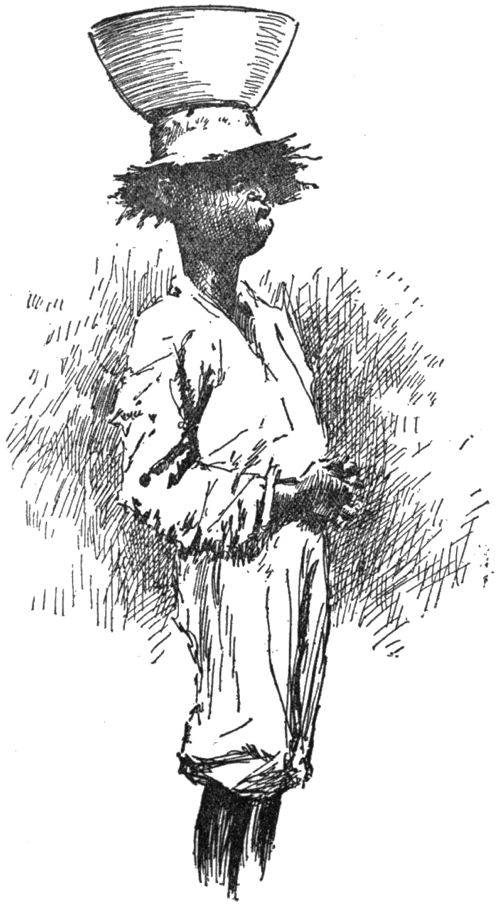

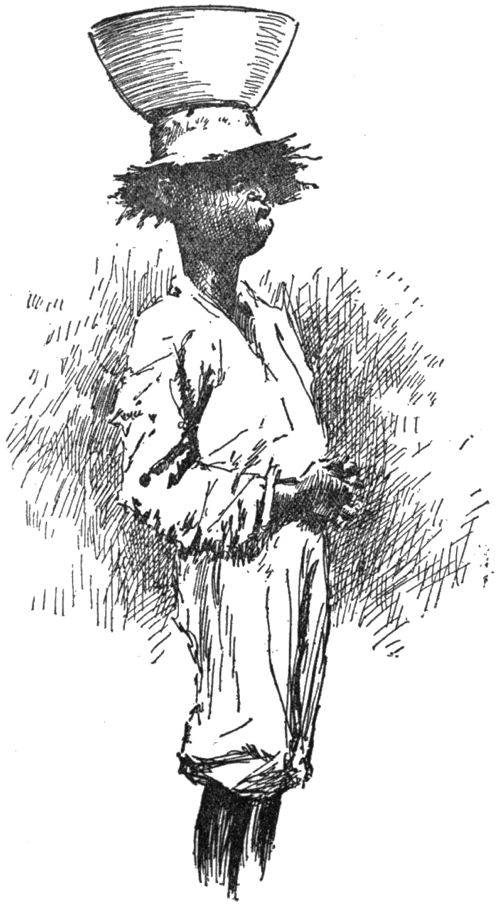

She wuz tall and big-boneded, and black as jet. Her hair, which wuz wool and partly white, wuz twisted up on top of her head and surmounted by a wonderful structure which she called a turben.

Sometimes this wuz constructed of a gorgeous red and yeller handkerchief, and sometimes it wuz white as snow; and when she wore this, she always wore a clean white neckerchief crossed on her breast, and a large white apron. She wore glasses too, which gave her a more dignified appearance. Evidently she wore these for effect, as she always looked over them, even when she took up a paper or book and pretended to be readin’ it; she could not read or write.

Indeed, when she had heavy work on hand, such as washin’, which made the situation of her best glasses perilous, I have seen her wear a heavy pair of bows, with no glasses in them whatever.

She evidently felt that these ornaments to her face added both grace and dignity.

AUNT MELA.

Her figure wuz a little bent with years, but the fire of youth seemed burnin’ still in her black eyes.

She boasted of havin’ lived in the best families in the South, and took great pride in relatin’ instances of the grandeur and wealth of the family she wuz raised in.

The name she went by wuz Aunt Mela.

I spoze her name wuz or should have been Amelia, but there wuzn’t no law violated, as I knows on, by her callin’ herself “Mela.” It wuz some easier to speak anyway.

I used to go down into the kitchen and talk quite a good deal with Aunt Mela.

At first she didn’t seem to relish the idee of my meddlin’ with her, but as days went on and she see that I wuz inclined to mind my own business, and to help her once in a while when she wuz in a bad place, she seemed to get easier in her mind, and would talk considerable free with me.

But she never thought anything of me compared to what she did of Maggie. She jest worshipped her; and Maggie wuz dretful good to her, gin her a sight besides her wages, and took care on her when she wuz sick, jest as faithful and good as she would of her own Ma or of me.

And Aunt Mela had sick spells often with what she called “misery in her back and misery in her head.”

I spoze it wuz backache and headache, that is what I spoze.

Wall, Aunt Mela sot store by Maggie, for the reasons I have stated, and then she liked her. And you can’t always parse that word and get the real true meanin’ of the why and the wherefore, why we jest take to some folks and can’t help it.

Wall, as I said, Aunt Mela wuz a wonderful good cook, a Baptist by persuasion, and I guess she meant to be as good as she could be, and honest. I believe she tried to be.

She had tried to keep the Commandments, or the biggest heft of ’em, ever sence she had jined the meetin’ house; and then she loved Maggie so well that she hated to wrong her in any way. But old influences and habits wuz strong in her, and she had common sense enough and honesty enough to recognize their power.

One day Maggie and I went out into the vegetable garden back of the house, and she had stopped in the kitchen for sunthin’, and she left the keys of the store-room in the lock.

And Aunt Mela come a hurryin’ after us into the garden with the keys in her hand.

“Miss Maggie, chile, hain’t I tole you not to lef’ dem keys in de lock, an’ now you’ve dun it agin.”

She wuz fairly tremblin’ with her earnestness, her white turben a flutterin’ in the mornin’ breeze and the air of her agitation.

“Why, Aunt Mela, you was there; what hurt would it do for me to leave them? You are honest, you wouldn’t take anything.”

“Miss Maggie, honey, chile, don’ you leave dem keys dah no moah. You say I’m hones’, an’ so I hopes I am. But den agin I don’ know. But when anybody can’t do sumpin’, den dey don’ do it, an’ don’ you leave dem keys dah no moah.”

“Why, Aunt Mela, I trust you,” sez Maggie in her sweet voice. “I know you wouldn’t do anything to hurt me.”

“To hurt you? No, honey. But den how can I tell when ole Mars Saten will jes’ rise up an’ try to hurt ole Mela? He may jes’ make me do sumpin’ mean jes’ to spite me for turnin’ my back on him. He jes’ hates Massa Jesus, ole Saten duz, an’ he’s tried to spite me ebery way sense I jine him.

“So you jes’ keep dem keys, Miss Maggie, and if ole Saten tells me to get sumpin’ outen dat stow room to teck to my sister down to Eden Centre, I’ll say:

“‘You jes’ go ’long! I can’t do it nohow, for Miss Maggie done got de keys.’”

Maggie took the keys and tried to keep them after this.

But she told me that many times Aunt Mela had warned her in the same way.

One day she had been tellin’ me a good deal about her trials and labors sence the War, and how she and her sister had worked to get them a little home, and how many times they had been cheated and imposed upon, and made to pay over bills time and agin, owin’ to their ignorance of business.

And I asked her if she thought she wuz any better off now than when she wuz a slave.

She straightened up her tall figure, put her hands on her hips, and looked at me over the top of her glasses.

“Betteh off, you say? You go lay down in de dahk, tied to de floah; if dat floah is cahpeted wid velvet an’ sahten, you’d feel betteh to get up an’ go way out on de sand, or de ston’—you feel free—you holt yur haid up—you breeve long brefs—you are free!”

“But,” sez I, “the floor of slavery wuzn’t covered with velvet, wuz it?”

“It wuz covered wid blood an’ misery. De dungeon house wuz heavy wid groans, an’ teahs, an’ agonies.

“My missy wuz good to me, as good as she could be to a slave. But all my chillen, one aftah anoder, wuz stole away from me.

“Aftah havin’ fo’teen chillen, lubbin’ ebery one ob ’em, like I would die ef dey wuz tuck away from me—aftah holdin’ dem fo’teen clost to my heart, so dey couldn’t be tuck nohow, I foun’ my ole ahms empty.”

She stretched out her gaunt old arms with a indescribable gesture of loneliness and woe, and went on in a voice full of the tears and misery of that old time: “I wuz kep’ jes’ to raise chillen for de mahket, dat wuz my business. An’ when I gin dem chillen my heart’s lub, dat wuz goin’ beyent my business.

“Slaves don’ hab no call to be humans nohow; if dey had hearts dey wuz wrung clear outen der bodies; if dey had goodness dey los’ it quick nuff.

“To try to be a good woman and true to your ole man wuz goin’ beyent yur business.

“Dey sole him too, de fader ob leben ob my chillen. He lubbed dem chillen too, jes’ as well Massy Allen lub little Missy Snow.

“He had to leab ’em—toah off, covered wid blood an’ gashes, for he fit for us, fit to stay wid me—we had libbed togedder sense I wuz fo’teen.

“I neber see him agin. He wuz killed way down in ole Kaintuck. He turned ugly aftah bein’ tuck from us, an’ den he wuz whipped, an’ he grew weak an’ homesick for us an’ his ole home. An’ den dey whip him moah to meck him wuck.

“And he daid off one day right when dey wuz a lashin’ him up. Didn’t see he wuz daid, kep’ on a whippin’ his cole daid body.”

Here Aunt Mela sunk down in a chair and covered her face in a corner of her apron, and rocked to and fro.

And I hain’t ashamed to say that I took out my white linen handkerchief and cried with her.

But pretty soon Aunt Mela wiped her eyes, adjusted her glasses agin, and went about her preparations for dinner.

And I jest hurried out of the kitchen, for my heart wuz full, full and runnin’ over.

And I gin her that very afternoon a bran new gingham apron, chocolate and white checks, all made up and trimmed acrost the bottom with as many as seven rows of white braid.

And I didn’t give her that apron a thinkin’ it would make up for the loss of her companion—no, indeed! What would store clothes be to me to take the place of my Josiah?

But I gin it to her to show my friendliness to her and to show her that I liked her, and to remind her that after she had been tosted and tore by the ragin’ billows she had got into a good harbor now, and a well-meanin’ one.

So I gin her the apron.

There wuz another family of colored folks who lived pretty nigh to Belle Fanchon, and I got to know considerable about them because they used to come after so many things to my son’s house.

Every day they came after milk or buttermilk—one little black face after another did I see there in the kitchen; but they all belonged to the same family, so I wuz told, and seemed to be of all ages between six and twenty. I could see they must take after the Bible some, for all of the children had Skripter names—Silus, and Barnibas, and Elikum, and Jedediah, and St. Luke, and more’n a dozen others, so it seemed to me.

Aunt Mela didn’t seem to think much on ’em. She said they wuz “lazy, no account, low-down niggers.”

But still, when we hearn that the mother wuz sick (the father wuz always sick, or said he wuz), I went to see her, and see she needed a dress bad—why, Aunt Mela took holt and showed quite a interest in our makin’ it.

We bought some good calico, chocolate ground with a red sot flower on it, and got her measure, and then we made it up as quick as we could, for she hadn’t a dress to her back, only the old ragged one that she had on.

Wall, we made it the easiest way we could; we started it for a sort of a blouse waist and a skirt, but Aunt Mela told us if we let ’em go that way she never would keep the skirt and waist together—there would always be a strip between ’em, for she wuz too lazy to keep ’em pinned together.

So we thought we would put some buttons on to fasten the skirt to the waist, and then we made a belt to go on over it of the same.

“DESPATCHED TO GET BUTTERMILK.”

“And as we wuz in a hurry, and knew the buttons wouldn’t show under the belt, we used some odd buttons out of Maggie’s button-bag, no two of a size or color, most of ’em pantaloons buttons, but some on ’em red ones, and one or two wuz white.

It looked like fury, but we knew the belt would cover it.

Wall, we made it, and I carried it down to her and explained the urgent necessity of the belt to her. And the very next day she wore it up to our house on a errant in the mornin’. I happened to be in the kitchen, and when she come in there I see the full row of pantaloons buttons a shinin’ out all round her waist, from the size of a dollar down to a pea.

As I looked on it, I know I looked strange.

And she asked me anxiously “if I wuz sick?”

And sez I, “Yes, sick unto death.”

She wuz too lazy and shiftless to put on that belt.

Sez I pretty severe like in axent, “Dinah, why didn’t you put on that belt?”

“Foh Gord, Missy, I cleen don fo’get it.”

“Wall, what good duz it do for us to work and make you a dress, if you are too shiftless to put it on?”

“Foh Gord, Missy, I dun no; spect nobody duz.”

“No,” sez I in a despairin’ axent, “nobody duz.”

The father could earn good wages at his trade, which wuz paintin’ and whitewashin’, and the mother wuz a good cook and laundress. And the boys wuz strong and healthy. But they would none of them work only jest enough to get a little something to eat and a few articles of clothin’, and then they would stop all labor, and none of the family work another day’s work till that wuz all used up.

Wall, she told me that day that her husband wuz sick agin, and they hadn’t any provisions; so we sent them down a sack of flour and a few pounds of butter.

They wuz sent about the middle of the forenoon and St. Luke wuz imegiatly despatched to get buttermilk—he wanted to get a good deal, he said, for they wanted enough to make a good many messes of biscuit. And Barnabas wuz sent out to borry some soda.

I sez to St. Luke, “Why don’t your Ma make riz bread? it would make the flour last as long agin, and then it would be fur more wholesome.”

And he told me that they didn’t love it so well.

Wall, we sent the buttermilk.

That night Thomas Jefferson wuz kep’ out late on business, and he passed their cabin at twelve o’clock at night, and he see the family all up, seated round the table eatin’.

And I asked Barnaby the next day, when he come on his usual errant for milk, if they wuz sick in the night.

And he told me that they wuzn’t sick, but his father got hungry in the night, and his mother got up and made some warm biscuit, and called ’em all up, and they had supper in the night—warm biscuit, and butter and preserves.

And I said to Maggie out to one side:

“They couldn’t seem to eat up their provisions fast enough in the daytime, so they had to set up nights to do it.”

And she said, “So it seemed.”

Wall, the man’s sickness wuz mostly in his stomach—pain in his stomach, so his wife told me.

And that wuz the reason she told me that she made warm biscuit so much.

And I told her it wuz the worst thing she could cook for him, for his health and his pocket.

But she said he loved ’em so well, and he wuz so kinder sick, she humored him dretfully; she said if anything should happen she shouldn’t have reflexions.

She said she always made a five-gallon jar of strawberry preserves; she worked out to get the sugar and she picked the strawberries herself, and she said they wuzn’t set on the table hardly any. When he didn’t feel well in the night, he would get up and take a spoon and eat out of that jar. And she ended agin by sayin’:

“I shouldn’t hab no ’flexions to cast onto myself if anyting should happen to my ole man.”

“Wall,” sez I in deep earnest, “if you keep on in this way you’ll find that sunthin’ will happen, for no livin’ stomach can stand such a strain cast onto it, unless it is,” sez I reasonably, “a goat or a mule. I have hearn that they can digest stove-pipe and tin cans. But a human stomach must break down under it. And I’d advise you to feed him on good plain bread and toast till he gets well, and keep your preserves for meal-times and company. And I’d advise you to set them great boys of yourn to work stiddy, and not by fits and starts, and you’ll have as much agin comfort in your house, and health too.”

But, good land! I might jest as well have talked to the wind, or better. For the wind, even if it didn’t pay no attention to my remarks—as it probably wouldn’t, specially if it wuz blowin’ hard—it wouldn’t get mad. It would jest blow right on, and blow my remarks right away, and blow jest as friendly as ever.

But she got mad—mad as a hen. And she didn’t send after milk for as much as three days. But it didn’t hold out; she sent on the fourth day.

But it didn’t change their course any. He kep’ on a eatin’ hot biscuit and butter and preserves, when they had ’em, night and day, and they all would. And when they hadn’t anything to eat, and couldn’t get anything in any other way, why, they would go without till they wuz most starved, and then they would sally out and work a day or two, and then the same scenes would be enacted right over agin.

Good land! there didn’t seem to be no use of talkin’, and still I sort o’ kep’ on.

There wuz one boy amongst ’em, and that wuz St. Luke, and mebby it wuz because he wuz named after that likely old apostel, and then, agin, mebby it wuzn’t; but anyway, he did seem to have a little more pride and a little more sense and gumption than the rest.

And I kep’ a naggin’ at him, and his Pa and Ma, and Thomas J. and Maggie, and Josiah, till with a tremendous effort I did get that boy into a new suit of clothes and started him off to work for his board and go to school at a place about three miles off. And though he run away five times in as many weeks—twice to come home and three times to go a fishin’—I kep’ on, and by argument, and persuasion, and a new jack-knife, and a coaxin’ him up, and persuadin’ the folks to try him a little longer, I got him quelled down, and he begun to go easier in the harness, and stiddier. And his teacher sez “he will make a smart boy yet.”

So I see jest what I always knew wuz a fact, “that while the lamp holds out to burn the vilest sinner may return.”

And if I wuz a goin’ to sing that him, I would omit two words in the last stanza, and for the words “vilest sinner” I would sing “shiftless creeter.”

For these two words are what will apply to his hull family, root and branch, specially the roots. Shiftless, ornary, no account, father and mother both; and bein’ full of shiftless, no account qualities, and bein’ married, what could they do, or be expected to do, but bring into the world a lot of still shiftlesser, no accounter creeters?

Inheritin’ shiftlessness, and lazyness, and improvidence on both sides, with their own individual lazyness and no accountness added, what can we expect of these offsprings?

But still I see in the case of St. Luke, as in the words of the him I quoted, that there is in education and the wholesome restraints of proper livin’ and trainin’ a hope for them—for the poor blacks and the poor whites, for the poor whites are jest as shiftless, jest as ignorant, and jest as no account.

“THE BIG PIAZZA.”