CHAPTER XV.

ABOUT five months after Rosy’s marriage her old grandmother’s “misery” become greater than she could endure, or ruther a sudden cold which she took proved fatal to her, and she took to her bed, and after a week’s illness passed away.

She wuz stayin’ with Rosy when she wuz took sick, and Maggie and I did everything we could do to relieve her wants and help her; but I see the first time I put my eyes on her face after her seizure that we could not help her—it wuz pneumonia; it carried her off after a few days of sufferin’.

The night before her death I went down to her cabin with a basket of jelly and broth and fruit, but she wuz beyend takin’ any nourishment.

She wuz propped up on pillows, her black face in marked contrast to the snowy linen that Maggie had furnished for her bed.

Genieve, patient nurse, wuz settin’ by her, her beautiful face wearin’ its usual look of triumphant sorrow, joyful ignominy, or—I don’t know as I can describe the look in words, but, anyway, she had the look she always had, different from anybody else’s, more sorrowful, more riz up, more inspired.

The Book of books wuz in her hand; she had been readin’ to her till she had fallen asleep.

At last Aunt Clo opened her eyes and looked up long and thoughtfully into the beautiful and pityin’ face bent above her, and finally she said to Genieve:

“Honey, did you come down out’n de Belovéd City dat you read me about?”

“Oh, no, Aunt Clo. Don’t you know me? I am Genieve, your old friend Genieve.”

“I done thought I see a light round your forehead, honey. It seems like I did see de light; sure you hain’t one of dem angels?”

“Oh, no, Aunt Clo; you know me, don’t you?”

And Genieve lifted her head and gave her a spoonful of the hot broth I had brought.

She sunk back on the pillow, and after a minute said, with the old persistency that Aunt Clo wuz wont to cling to any idee she had formed:

“It jess seems as if I did see de light a shinin’ down out of your eyes, honey, into my ole heart.”

A more peaceful look settled down upon the face that had been drawn and seamed with “the misery.” And when she fell into her last sleep the same expression remained.

And I wondered if indeed Genieve’s sweet soul did not by some magnetism of attraction draw down a band of bright spirits whose heavenly looks wuz reflected upon her own, and if indeed a glow from the heavens she tried to picture to the old black woman might not be reflected dimly into her poor old heart.

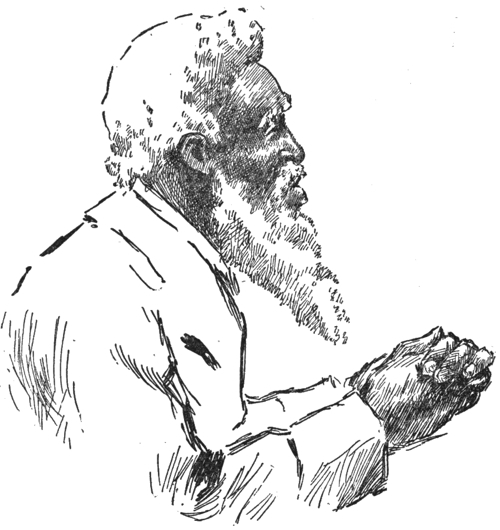

“WHEREFOAH, BREDREN, LET US PRAY.”

But we see through a glass darkly; we may not see clearly into the beauties and wonders of the Belovéd City.

Genieve stayed and rendered all the assistance she could. She stayed as long as she wuz needed.

But as soon as the news got out that Aunt Clo wuz dead, a crowd of her relations, near and distant, come in and took possession of the cottage and begun preparations for an elaborate funeral.

A colored minister wuz sent for, and he preached a long sermon in which her virtues wuz held up as a pattern, and her sudden death as a warnin’ for ’em all to be ready for “de Master’s call, which might come in de night time, or in de heat and burden of de day, but wuz shuah to come. Shuah, young, careless girl; shuah, gay, happefyin’ young man, for de trumpet must sound, and de dead must go at de bugle call of de Reapeh.

“He reaps de flowehs of de gahden,” sez he, pintin’ to the grave of Belle Fanchon, which wuz not fur from the cabin-door.

“He reaps de flowehs in all deir beauty, an’ de ripe grain an’ de wheat. Dis wheat we lay in de grave to-day, knowin’ dat de incorruption will rise up incorruptible, an’ de glory will come up glorious, an’ we shall all see it in de twinklin’ of de eye—an’ wherefoah, bredren, let us pray.”

And he knelt down and offered up a prayer full of faith, and pathos, and the wise ignorance of his childlike race.

Rising up from his knees, he directed the mourners to pass in front of the coffin and view the remains, which they did with loud groanings and many tears and exclamations of grief.

Then the coffin wuz closed, and the minister stood up in front of it and sez:

“Christians, fall into line.”

And the church-members silently fell into line two by two till they wuz all in their places.

Then he sez, “Sinners, fall into line.”

And the irreligious came forward jest as calmly and took their places, and the procession moved off, and Aunt Clo wuz carried away to her last sleep, in a little colored graveyard some mile and a half away.

I told Josiah about it after I got home; I sez:

“The good and the bad always foller on after every departed friend; but I never see ’em sorted out so careful before, and I never see such a calm willingness to be put amongst the goats as I see there.”

“Wall,” sez he, “they knew they wuz goats, so what wuz the use of kickin’?”

“Wall,” sez I, “I have seen white folks lots of times that must have known they wuz goats, but they didn’t love to be sorted out on the left side, and no money could have made ’em walk up and fall into a sinner’s line.”

Sez he, “If they be sinners, why can’t they own up to it? I would if I wuz a sinner.”

But I felt that it wuz ofttimes hard work to tell the difference; and I sez:

“I am glad it hain’t me that has to do the separatin’ between the good and the bad, for I shouldn’t know where to lay holt, appearances are so deceitful sometimes. Sheepskins are wore often over goats, and anon a sheep puts on the skin and horns of a goat to face the world in and fight with it. I shouldn’t know where to begin or leggo.”

“Wall, that is because you are a woman,” sez Josiah. “Wimmen never know where or how to lay holt of any hard work or head work. I could do it in a minute, and any man could that wuz used to horned cattle.”

I sithed and thought to myself the thought I had entertained more or less ever sence I stood up with Josiah Allen at the altar. How different, how different my pardner and I looked on some things, and how impossible it wuz seemingly for us to ever get the same view on ’em.

But I didn’t multiply any more words with him, knowin’ it wouldn’t be of any use; and then agin, as I looked clost at him, I see a shade of serious pensiveness, and even sadness, as it were, a shadin’ down onto his eyebrow.

And my talk didn’t seem to lighten it any as I went on and told him that they said that this custom of dividin’, as it were, the sheep and the goats wuz practised a good deal in different parts of the South.

But I still see the shadowy shade on his foretop, and went on more cheerful, and told him that the little boy Abe wuz goin’ to be took into the family of the good colored preacher, so he wuz sure of a good home and good treatment.

But in vain wuz all my cheerful perambulations of conversation. I see that he looked demute, and broodin’ over some idee; and finally he spoke out:

“Samantha, goin’ to funerals, or hearin’ about ’em, puts folks to thinkin’.”

“Yes, it duz, Josiah;” and sez I, in quite a solemn axent, “it stands us all in hand to be prepared.”

ABE.

Sez he, “I wuzn’t thinkin’ of that side of the subject, Samantha; but it brings back to me that old thought and fear that has been growin’ on me for years more or less. Samantha,” sez he, “I worry, and have worried for years, for fear that you will some time be left a relict with nuthin’ to lean on.”

I glanced up at him, and the thought come to me instinctively that it would be the ondoin’ of us both if I should try to lean heavy on him now, for my weight is great, and he is small-boneded, and I knew that he would crumple right down under the weight of 200 pounds heft.

But I didn’t speak my thoughts—oh, no; I merely looked at him real affectionate, and I took up a sock I wuz mendin’ for him (we wuz in our own room), and I attackted it as socks should be attackted if you lay out to make ’em good and sound. And he went on still more confidential and confidin’, and told me several things he thought I had ort to do if I wuz ever left a relict of him.

It wuz real touchin’, and I wuz considerable affected by it—not to tears—no; I thought I wouldn’t shed any tears if I could help it, for darnin’ is close work, and it calls for all the eyesight you have got; and then I had on a new gray lawn dress that I felt would spot easy; so I restrained my emotions with a almost marble composure, and anon I sez to him as he wuz a goin’ on in that affectin’ way, and sez I:

“I may be took first, Josiah Allen.”

And he admitted that that might be the case, though he couldn’t bear to think on’t, he said, it gin him such awful feelin’s.

He said he had never been able to think on’t with any composure. But after a while he talked more diffuse on the subject, and owned up that he had thought on’t; and sez he, in a still more confidin’ and affectionate way:

“For years, Samantha, I have had it in my head what I would put on your tombstun if I should live to stand up under the hard, hard blow of havin’ to rare one up over you.

“I have thought I should have it read as follers, and to wit, namely:

“‘Here lies Samantha, wife of Deacon Josiah Allen, Esquire, of Jonesville. Deacon in the Methodist Church, salesman in the Jonesville cheese factory, and a man beloved and respected by every one who knows him but to love him, and names him but to praise.’

“Its endin’ in poetry, Samantha, wuz jest what I knew wuz touchin’, dumb touchin’, and would be apt to please you; and it is always a man’s aim to write the obituarys of his former deceased pardner in a way that would suit her and be pleasin’ to her.”

Sez I calmly, “Yes, I should know a man wrote that if I read it in the darkest night that ever rolled, and I wuz blindfolded.”

“Wall,” sez he anxiously, “don’t it suit you? Don’t you think it is uneek, sunthin’ new and strikin’?”

“Oh, no,” sez I, “no, it hain’t nuthin’ new at all; but mebby it is strikin’—or that is,” sez I, “it depends on who is struck.”

“Wall,” sez he, “it is dumb discouragin’, after a man racks his brains to try to get up sunthin’ strong and beautiful, to think a woman can’t be tickled and animated with it.”

Sez I calmly, “I hain’t said that I wuzn’t suited with it.” And sez I with still more severe axents, for I see he looked disappointed, “I will say further, Josiah, that it meets my expectations fully; it is jest what I should expect a male pardner to write.”

“Wall,” sez he, lookin’ pleaseder and more satisfieder, “I thought you would appreciate it after you thought it over for a spell.”

“I do, Josiah,” sez I, turnin’ over the sock I wuz a mendin’ and attacktin’ a new weak spot in the heel, “I do appreciate it fully.”

Josiah looked real tickled and sort o’ proud, and I kep’ on in calm axents and a darnin’ too, for the hole wuz big, and night wuz a descendin’ down onto us. And I could hear Aunt Mela’s preparations for supper down below, and I wanted to get the sock done before I went down-stairs. So I sez, sez I:

“I have thought about it sometimes too, Josiah, and I have got it kinder fixed out in my mind what I would have on your tombstun—if I lived through it,” sez I with a deep sithe.

“What wuz it?” sez he in a contented tone, for he knows I love him. “It is poetry, hain’t it?”

“Yes,” sez I calmly, “I laid out to end it with a verse of poetry; it wuz to run as follers: ‘Here lies Josiah Allen, husband of Samantha Allen, and—’”

“Hold on!” sez Josiah, gettin’ right up and lookin’ threatenin’. “Hold on right there where you be; no such words as them is a goin’ on my tombstun while I have a breath left in my body. Husband of—Josiah, husband of—I won’t have no such truck as that, and I can tell you that I won’t.”

“Be calm, Josiah,” sez I, “be calm and set down,” for he looked so bad and voyalent that I feared apperplexy or some other fit. Sez I, “Be calm, or you will bring sunthin’ onto yourself.”

“I won’t be calm, and I don’t care what I bring on, and I tell you I ruther bring it on than not, a good deal ruther. The idee! Josiah Allen, husband of—It has got to a great pass if a man has got down to that—to be a husband of—”

“Why,” sez I, lookin’ up into his face stiddily, as he stood over me in a wild and threatenin’ attitude—and some wimmen would have been skairt and showed it out; but I wuzn’t. Good land! don’t I know Josiah Allen, and through him the hull race of mankind? I knew he wouldn’t hurt a hair of my foretop, but he would like to skair me out of the idee, that I knew.

But sez I in a reasonable axent, “You had got it all fixed out ‘Samantha, wife of Josiah—’”

“Wall, that is the way!” sez he, hollerin’ enough almost to crack my ear-pan—“that is the way every man has it on his pardner’s headstun. Go through the hull land and see if it hain’t; you can look on every stun.”

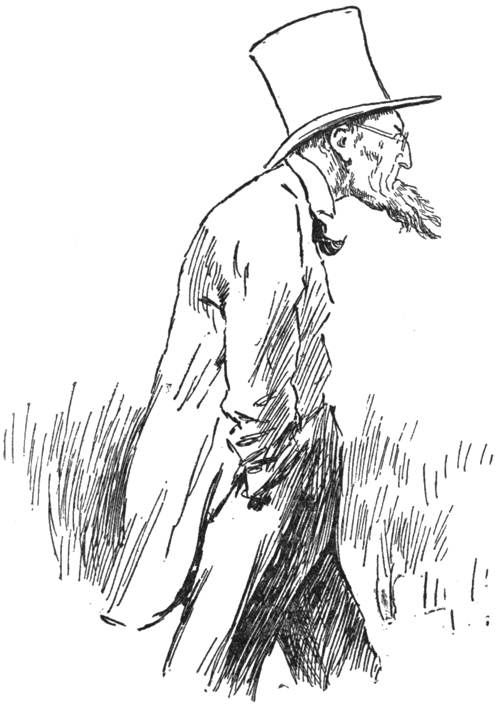

“HE WUZ A WALKIN’ UP AND DOWN.”

Oh, how that “stun” rolled through my head! And sez I, “I am not deef, Josiah Allen, neither am I in Shackville, or Loontown, or the barn. Do you want to raise a panic in your son’s household? Moderate your voice or you will harm your own insides. I know it is the way every man has wrote it about their pardners, and it seemed so popular amongst men I thought I would try it.”

“Wall, you won’t try it on me!” he hollered as loud as ever. “You won’t try it on me, and don’t you undertake it. Why, ruther than to have them words rared up over me I would—I would ruther not die at all. ‘Josiah Allen, husband of—’ No, mom, you don’t come no such game over me; you don’t demean me down into a ‘husband of—’!”

“Why,” sez I, lookin’ calmly into his face (for I see I must be calm), “don’t you know how I have wrote my name for years and years, ‘Josiah Allen’s Wife’?”

“Wall, that wuz the way to write it; it wuz stylish,” he yelled. Oh, how he yelled! Why, that “stylish” almost broke a hole through my ear-pan; the pan jest jarred, it wuz so voyalent.

Sez I, “Set down, Josiah, and less argue on it.”

“I won’t argue on it, it is too dumb foolish; I am goin’ out to walk in the back garden before supper.”

And he ketched down his hat and drawed it down over his ears enough to break ’em off if they hadn’t been well sot on, and slammed the door so one of them panels is weak to this day—it wuz a little loose to start with.

And I went and stood in the winder with my hand over my eyes, and watched him all the while he wuz a walkin’ up and down them walks, for I wuz most afraid he would totter and fall over, or mebby he would start off a bee-line for the crick and drown himself, he wuz so rousted up and agitated. And I hain’t dasted to open my head sence on the subject—I don’t dast to, not knowin’ what it would bring onto him. At the table they noticed my pardner’s excited and riz up mean—they couldn’t help it.

And Maggie asked him “if he wuzn’t feelin’ well.”

And I spoke right up, such is a female’s devoted love for her companion—I spoke right up and sez:

“We have been a talkin’ over funerals and such, and your Pa got agitated.”

I spoze I told the truth—I spoze I did; I didn’t tell what the “such” wuz that he had been a talkin’ about; I don’t know as I wuz obleeged to.

“THIS DARK EARTH VALLEY.”