CHAPTER XX.

THE relation on Maggie’s side is dead. Some said of heart failure, others said of a broken heart caused by disappointed ambition.

Yes, somebody else got higher than he wuz, and he fit too hard. Goin’ round electioneerin’, makin’ speeches by night, travellin’ by day, pullin’ wires here and pullin’ wires there, bamboozlin’ this man, hirin’ that man, bribin’ the other man, and talkin’, talkin’, talkin’ to every one on ’em. Climbin’ hard every minute to get up the high mount of his ambition, slippin’ back agin anon, or oftener, and mad and bitter all the time to see his hated rival a gettin’ nearer the prize than he wuz.

No wonder his heart failed. I should have thought it would.

So little Raymond Fairfax Coleman wuz left a orphan. And in his father’s will, made jest after that visit to my son Thomas Jefferson, he left directions that Raymond should live with his Cousin Maggie and her husband till he wuz old enough to be sent to college, and Thomas J. wuz to be his gardeen, with a big, handsome salary for takin’ care of him.

There wuzn’t nuthin’ little and clost about the relation on Maggie’s side, and as near as I could make out from what I hearn he kep’ his promise to me. And I respected him for that and for some other things about him. And we all loved little Raymond; and though he mourned his Pa, that child had a happier home than he ever had, in my opinion.

And I believe he will grow up a good, noble man—mebby in answer to the prayers of sweet Kate Fairfax, his pretty young mother.

She wuz a Christian, I have been told, in full communion with the Episcopal Church. And though the ministers in that meetin’ house wear longer clothes than ourn duz, and fur lighter colored ones, and though they chant considerable and get up and down more’n I see any need of, specially when I am stiff with rheumatiz, still I believe they are a religious sect, and I respect ’em.

Wall, little Raymond looked like a different creeter before he had been with us a month. We made him stay out-doors all we could; he had a little garden of his own that he took care of, and Thomas J. got him a little pony. And he cantered out on’t every pleasant day, sometimes with Boy in front of him—he thinks his eyes of Boy. And before long his little pale cheeks begun to fill out and grow rosy, and his dull eyes to have some light in ’em.

“MAKIN’ SPEECHES.”

He is used well, there hain’t a doubt of that. And he and Babe are the greatest friends that ever wuz. They are jest the same age—born the same day. Hain’t it queer? And they are both very handsome and smart. They are a good deal alike anyway; the same good dispositions, and their two little tastes seem to be congenial.

And Josiah sez I look ahead! But, good land! I don’t. It hain’t no such thing! The idee! when they are both of ’em under eight.

But they like to be together, and I am willin’ they should; they are both on ’em as good as gold.

And on Babe’s next birthday, which comes in September, I am goin’ to get, or ruther have my companion get her a little pony jest like Raymond’s. I have got my plans laid deep to extort the money out of him. Good vittles is some of the plan, but more added to it.

I shall get the pony, or ruther it will be got. And if them two blessed little creeters can take comfort a ridin’ round the presinks of Jonesville on their own two little ponys, they are goin’ to take it.

Life is short, and if you don’t begin early to take some comfort you won’t take much.

But to resoom. The relation on Maggie’s side has passed away, but the relation on Josiah’s side is still in this world, if it can be called bein’ in this world when your heart and spirit are a soarin’ up to the land that lays beyend.

But I guess it would be called bein’ in this world, sence his labor is a bein’ spent here, and his hull time and strength all ready to be gin to them who are in need.

He is doin’ a blessed good work in Victor, for so their colony is named, after the noble hero who laid down his life for it.

And the place is prosperin’ beyend any tellin’. All that Genieve dreamed about it is a comin’ true.

And she is a helpin’ it on; she spends her money like water for the best good of her people.

She didn’t raise no stun monument to Victor; no, the monument she raised up to his memory wuz built up in the grateful hearts of his people.

Upon them, his greatest care and thought when here, she spends all her life and her wealth.

She felt that she would ruther and he would ruther she would carve in these livin’ lives the words Love and Duty than to dig out stun flowers on a monument.

And she felt that if she wuz enabled to cleanse these poor souls so the rays of a divine life could stream down into ’em, it wuz more comfort to her than all the colors that wuz ever made in stained glass.

She might have done what so many do—and they have a right to do it, there hain’t a mite of harm in it, and the law bears ’em out—

She might have had lofty memorial winders wrought out of stained glass, with gorgeous designs representin’ Moses leadin’ his brethren through the Red Sea, or our Saviour helpin’ sinners to better lives—

And white glass angels a bendin’ down over red glass mourners, and rays of glass light a brightenin’ and warmin’ glass children below ’em.

There hain’t a mite of harm in this; and if it is a comfort to mourners, Genieve hadn’t no objection, and I hain’t. And the more beauty there is, natural or boughten, the better it is for this sad old world anyway.

But for her part, Genieve felt that she had ruther spend the wealth of her love and her help upon them that suffered for it.

FATHER GASPERIN.

Upon little children, who, though mebby they didn’t shine so much as the glass ones did, but who wuz human, and sorrowful, and needy. Little hearts that knew how to ache, and to aspire; innocent, ignorant souls whose destiny lay to a great extent in the ones about ’em; little blunderin’ footsteps that she could help step heavenward.

By the side of the plain but large and comfortable church in the colony there wuz a low white cross bearin’ Victor’s name.

But within the church, in the hundreds of souls who met there to worship God, his name and influence wuz carved in deeper lines than any that wuz ever carved in stun.

It wuz engraved deep in the aspirin’ lives of them who come here to be taught, and then went out to teach the savage tribes about them.

Many, many learned to live, helped by his memory and his influence; many learned how to die, helped by his memory and his example.

Good Father Gasperin, who went with the colony, has passed away. He preached the word in season and out of season. And his death wuz only like the steppin’ out of the vestibule of a church into the warm and lighted radiance of the interior.

He knew whom he had believed. He had seen the good seed he had sown spring up an hundred fold, and ripenin’ to the harvest, that sown agin and agin might yield blessed sheaves to the Lord of the harvest.

And when the summons come he wuz glad to lay down his prunin’ knife and his sickle and rest.

The same sunset that gilds the mound under which he sleeps looks down upon a low cottage not very fur away.

It stands under the droopin’, graceful boughs of a group of palm-trees that rise about it, its low bamboo walls shinin’ out from the dark green screen of leaves.

An open veranda runs round it half shaded with gorgeous creepin’ vines glowin’ and odorous, more beautiful than our colder climate ever saw.

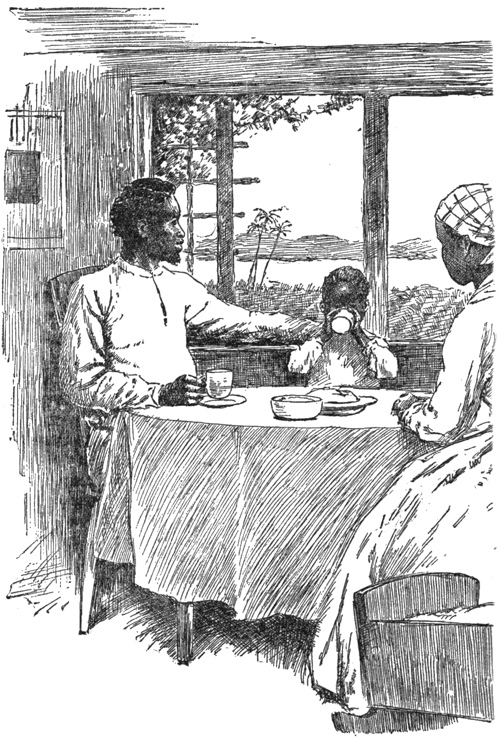

“FELIX, HIS WIFE AND LITTLE NED.”

Inside it is simple but neat. The bare floors have a few rugs spread upon them, a few pictures are on the walls. A round table stands spread in a small dinin’ room, with a snowy cloth woven of the flax of old Georgia upon it.

Round the table are grouped Felix, his wife and little Ned. In a cradle near by lies a baby boy born in the New Republic; his name is Victor, and he is the pet of Genieve, whose cottage, much like this, stands not fur away.

Through the open lattice Felix sits and looks out upon his fields. It is a small farm, but it yields him a bountiful support.

He and Hester have all they want to eat, drink, and wear, and their children are bein’ educated, and they are free.

The vision that Genieve saw in the sunset light at Belle Fanchon has not fully come yet, but it is comin’, it is comin’ fast. Little Victor may see it.

Genieve and Felix and Hester write to us often, and specially to Thomas Jefferson, who has been able to help the colony in many ways, and wuz glad to do it.

For Thomas Jefferson, poor boy, though I say it that mebby shouldn’t, grows better and better every day; but then I hain’t the only one that sez it. He found poured out into his achin’ heart the baptism of anguish that in such naters as hisen is changed into a fountain of love and helpfulness towards the world.

His poor, big, achin’ heart longed to help other fathers and mothers from feelin’ the arrow that rankled in his own.

His bright wit become sanctified into more divine uses. His fur-seein’ eyes tried to solve the problems of sad lives, and found many a answer in peace and blessedness for others that reflected back into his own.

More and more every day did the memory of little Snow, so heart-breakin’ at first, become a benediction to him, and a inspiration to a godlier livin’. He could not entertain a wilful sin in the depths of the heart where he felt them pure, soul-searchin’ eyes wuz lookin’ now.

He couldn’t turn his back onto the Belovéd City, where he felt that she wuz waitin’ for him. No, he would make himself worthy of bein’ the father of an angel. He must make his life helpful to all who needed help.

And to them that she felt so pitiful towards, most of all the dark lives full of sin and pain, he must help to light up and sweeten by all means in his power. And Maggie felt jest like him, only less intenser and more mejum, as her nater wuz.

Thomas Jefferson and Maggie jined the Methodist meetin’ house on probation, the very summer after little Snow left them.

And, what wuz fur better, they entered into such a sweet, helpful Christian life that they are blessin’s and inspirations to everybody that looks on and sees ’em.

To Raymond and Robbie they give the wisest and tenderest care. The poor all over Jonesville, and out as fur as Loontown and Shackville, bless their names.

And at Belle Fanchon, where they always lay out to spend their winters, their comin’ is hailed as the comin’ of the spring sun is by the waitin’ earth.

The errin’ ones, them from whom the robes of Pharisees are drawed away, and at whom noses are upturned, these find in my boy Thomas Jefferson and his wife true helpers and friends. They find somebody that meets ’em on their own ground—not a reachin’ down a finger to ’em from a steeple or a platform, but a standin’ on the ground with ’em, a reachin’ out their hands in brotherly and sisterly helpfulness, pity, and affection.

Dear little Snow, do you see it? As the tears of gratitude moisten your Pa’s and Ma’s hands, do you bend down and see it all? Is it your sweet little voice that whispers to ’em to do thus and so? Blessed baby, I sometimes think it is.

Mebby you turn away from all the ineffable glories that surround the pathway of the ransomed throng, to hover near the sad old earth you dwelt in once and the hearts that held you nearer than their own lives. Mebby it is so; I can’t help thinkin’ it is sometimes.

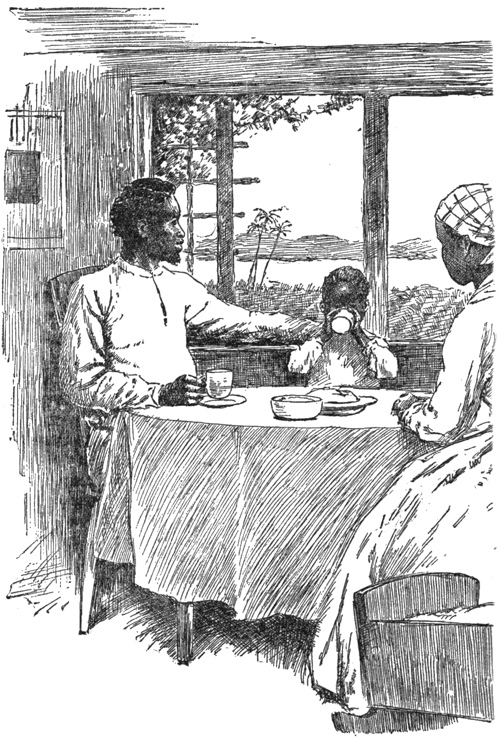

I said that the relation on Josiah’s side is still in the world, and I believe it, because we had a letter from him no longer ago than last night. I got it jest before sundown, and after Josiah handed it to me he went to the barn to onharness—he had been to Jonesville.

“I SOT OUT ON THE STOOP.”

I sot out on the stoop under the clear, soft twilight sky of June, and the last red rays of the sinkin’ sun lay on the letter like a benediction. And under that golden and rosy light I read these words:

“MY DEAR COUSIN: Here in this distant land, where my last days will be spent, my human heart yearns over my far-off kindred.

“And I send you this greeting and memorial to testify that the Lord has been gracious to me. He has permitted me to see the desire of my heart. He has blessed my failing vision with the blessed light of this Land of Promise.

“I sit here as I write on the banks of a clear river that runs towards the South land.

“My little cabin stands on its banks, and I sit literally under my own vine and fig-tree, and I can say of my home as the prophet of old said of a fair city: ‘It is planted in a pleasant place.’

“As my eyes grow dim to earthly things I catch more vividly the meaning of immortal things hidden from me in my more eager and impetuous days.

“I am now willing to abide God’s will.

“I see, in looking back to those old days, that I was impatient, trying to mould humanity according to my poor crude conception.

“I am now willing to wait God’s will.

“I see it plainly working out the great problem which vexed me so sorely.

“How slowly, how surely has this plan been unfolding, even in those long days of slavery, when the eager and impetuous ones distrusted God’s mercy and scouted at His wisdom.

“But how else was it possible to have taken these ignorant ones from the jungles of Africa and made of them teachers and missionaries of Christianity and civilization to their own people?

“How else could the story of Christ’s life and Christ’s sufferings and risen glory have been so clearly revealed to them as when they were passing through deep waters and coming up out of great tribulations?

“Out of the wrath of men He made his will known. While they suffered they learned the fellowship of suffering as they could not by any tongue of missionary or teacher.

“While they were in bonds they learned something of the patience and long suffering of Him who endured.

“While the war was raging on each side of them and they passed unharmed out through the Red Sea, while the contending hosts fell about them on every side, they learned of the strength of the Lord, the sureness of His protecting care.

“While they were encamped in the dark wilderness between the house of bondage and the Promised Land, they learned to wait on the Lord.

“And in that long waiting they brightened up the sword of wisdom and the spirit so they could vanquish the hosts of ignorance surrounding the land from whence they were taken in their black ignorance, and to which they returned rejoicing, ready to work for Him who had redeemed them.

“I look into the future and I see the hosts of ignorance, and superstition, and idolatry falling before the peaceful warfare of these soldiers of the cross.

“I see the idols of superstition and bestial ignorance falling and the white cross lifted up and shedding its pure, awakening light over the hordes of savage men and savage women brought in, washed and made clean, to the marriage supper of the Lord.

“As for myself, I truly care not how long I may wait my Master’s call. For whatever pathway I may tread, in this world or the other, I know that He that is risen will go before me; so I fear not the way by land, however long, nor the swelling of Jordan.

“And either in the body or out of the body, God knoweth best. I shall see the fulfilment of His promises, I shall see the working out of His plan as it draws nearer and nearer to its perfect fulfilment.”

I dropped the hands that held that letter into my lap, and sot there in silence.

The sun had gone down, but the west wuz a glowin’ sea of pale golden light, and above it a large clear star shone like a soul lookin’ down into this world, a soul that had got above its troubles and perplexities, but yet one that took a near and dear interest in the old world yet.

Fur off, away over the peaceful green fields, I could hear the cow-bells a tinklin’ and a soundin’ low and sweet, as the herds wended their way home through the starry dusk.

Everything wuz quiet and serene.

And as I sot there my heart sort o’ waked up, and memories heavenly sweet, heavenly sad, come to thrill my soul as they must always do while I stay here below, till my day of pilgrimage is over.

But as I sot there with tears on my cheeks and a smile on my lips—for I wuzn’t onhappy, not at all, though the tears wuz in my eyes through thinkin’ of such a number of things—all at once a light low breeze swept up gently from the south or down from the glowin’ heavens—anyway it come—and swept lovingly and kind o’ lingeringly, as if with some old lovin’ memory, over the posies in the door-yard, and sort o’ waved the sweet bells of the mornin’ glories, and fell on my forehead and cheek like a soft, consolin’ little hand.

It sort o’ stayed there and caressed me, and brushed my hair back, and then touched my cheek, and then—wuz gone.