CHAPTER XII.

ROBERT BURNS AND HIGHLAND MARY.

Wall, from here we took some excursions to places of interest in the vicinity. One of heart-thrillin’ interest wuz to Ayr, and lasted two days, for Martin said he wanted to see every spot connected in any way with Robert Burns. He said he didn’t care about readin’ his historys and sermons, but it seemed to be the stylish and proper thing to do, so he wouldn’t fail of doin’ it for anything. So we sot off one mornin’ with great anticipations, and each on us a satchel, for the forty milds trip.

Josiah wuz riz up in his mind about Sir William Wallace—more so than he wuz with Burns.

For the “Scottish Chiefs” had been read by him with avidity in his boyhood, and permeated his fancy, and he still thought it wuz the most thrillin’ book that wuz ever wrote, exceptin’ “Alonzo and Melissa.” “That,” he said, “never will be equalled for heart-breakin’ interest.”

So as we journeyed along he talked a sight about Wallace and that claymore of hisen. “Why,” sez he, “it must have weighed 4 hundred or 5 hundred pounds. What a man he wuz to wield it as he did and cut down his enemies with it!

“Why,” sez he, “it would take two common men to lift it, they say, and what a sight it must have been to see him swingin’ that round his head and mowin’ down his enemies jest as Ury would mow down oats!”

Sez I, “Josiah, I hope you are too good to enjoy sech a blood-curdlin’ sight, if it ever took place, but you must be careful about believin’ everything you hear about Wallace. I suppose that, like King Arthur, an old Illiad that Thomas J. ust to read about so much, lots of things has been told about him that never took place.”

“Take care, Samantha; I can stand a good deal from a pardner, but when you go to doubtin’ William Wallace, then is the time for a man to take a stand.

“Why, you’ll be a-doubtin’ ‘Thaddeus of Warsaw’ next. I wuz brung up on them books,” sez he, “and on them books I take my stand. If I’d hefted that claymore myself, I couldn’t believe in it any more ’n I do.”

Sez I, a-tryin’ to bring him back into the plains of megumness and reason—

“You know history sez that Wallace wuz a sheep-stealer, in the first place. Don’t pin your faith onto him too much, Josiah Allen.”

“A sheep-stealer!”

Wall, I will pin up a heavy shawl between Josiah Allen and the public for the next few minutes. I guess I’ll hang up my Paisley shawl, that’s pretty thick, and I too will withdraw myself behind it.

Suffice it to say when we emerged from behind it, I wuz a-sayin’—

“Wall, wall, I spoze like as not he did own a claymore, Josiah Allen, and I dare say it wuz a pretty hefty one.” And then I turned the subject off onto Robert Burns, and bagpipes, and sech.

Truly there is a time for pardners to stand their ground, and a time for ’em to gin in. When they see blood-vessels are on the pint of bustin’ and pardners are chokin’ with rage—gin in to ’em if you can, and keep your principles.

I allers foller this receipt, and it has bore me on triumphant.

Truly great is the mystery of pardners.

Wall, Josiah got real sentimental a-talkin’ about Wallace’s first wife, Marion, and his second wife, Helen Mar. “You know,” sez Josiah, “Helen said in them last hours—‘My life must expire with his.’”

And I sez, “Wall, it did at jest about the same time—she died of a broken heart,” sez I, bein’ willin’ to talk kind o’ sentimental with him, and soothe him down.

“Yes,” sez Josiah, “and don’t you remember what Bothwell said ‘as he raised her clay-cold face from Wallace’s coffin’—

“‘They loved in their lives, and in their deaths they shall not be divided’?”

Josiah was dretful sentimental at them reminescences, but he gradually chirked up agin, and by the time we come in sight of that tower of William Wallace’s, in Ayr, more’n a hundred feet high, Josiah’s sperits riz up almost as high as that tower.

Ayr is the seen of some of the most thrillin’ events of Wallace’s life. Here he would sally out aginst his enemies—here he wuz took by ’em and imprisoned. Here Robert Bruce and his troops made it their headquarters for a spell, and so did Cromwell and his army.

It is a dretful interestin’ spot on lots of accounts, but on none of ’em so much as bein’ the birthplace of Robert Burns.

The humble cottage where the immortal flower of Genius sprung up like a tall white lily out of the dust of the wayside—

This cottage is on the banks of Bonny Doon—

There Simmer first unfaulds her robes,

And there she langest tarries,

And there he took his last farewell

Of his sweet Highland Mary.

The immortal tenderness and sweetness of that love meetin’ and partin’ has made the waters of Bonny Doon ripple along full of the melodies of the past.

In Nater there is a universal tendency to retain the good and beautiful, and forgit the commonplace and dreary. We forgit the steamin’ vats and big cheeses Mary must have had to turn and lift at her place of service, Gavin Hamilton’s, or, as Burns called it—“The Castle of Montgomerie.”

We forgit all the toilsome labor that must have turned Mary’s pretty hands brown and hard, and made her slim back ache.

We forgit the achin’ “Ploughman shanks” the laborer Burns must have carried sometimes to their trystin’ place beside the Bonny Doon.

For though you may lighten the labor of ploughin’ by religious poems, like the “Cotter’s Saturday Night,” or brave, heroic ones, like “Scots wha hae wi’ Wallace bled,” or verses to “A Mouse” and “A Mountain Daisy”—

“Wee sleekit, cowerin’, tim’rous beastie,”

and

“Wee modest, crimson-tippéd flower,”

and “Brigs” and “Glens” and “Water-fowls—”

And though he may have added a flavor to it by sarcastic verses to “Holy Willie,” and “The Deil,” and “The Unco Guid”—

Yet to hold the heavy plough as it tore its long furrows in the flinty soil wuz weary work, and the back and arms of the poet must have ached as sorely as any other ploughman’s.

But you forgit all that; they dwell here forever care free, serene in glowin’ youth and beauty.

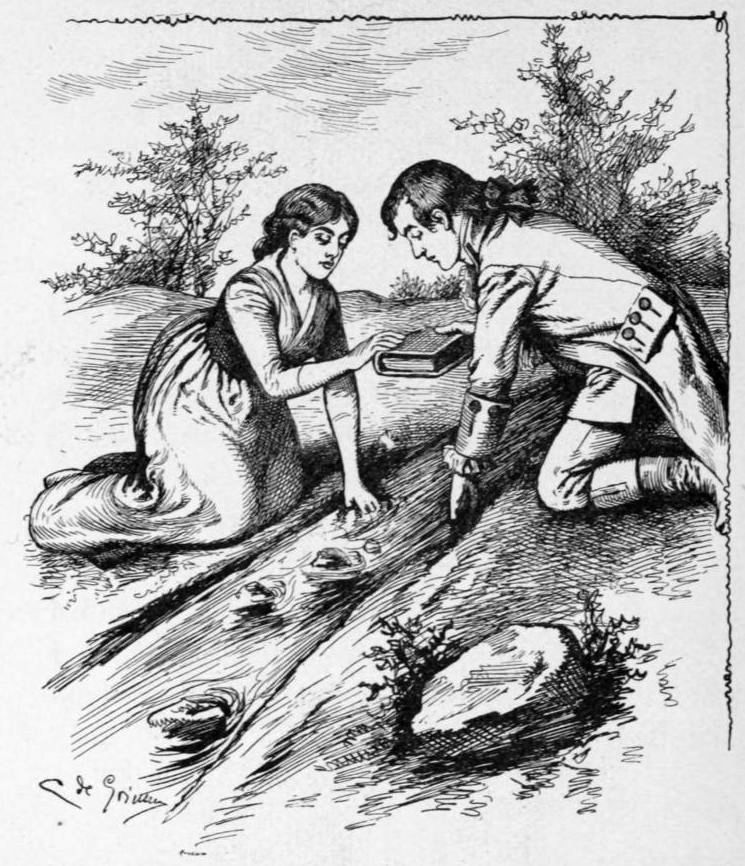

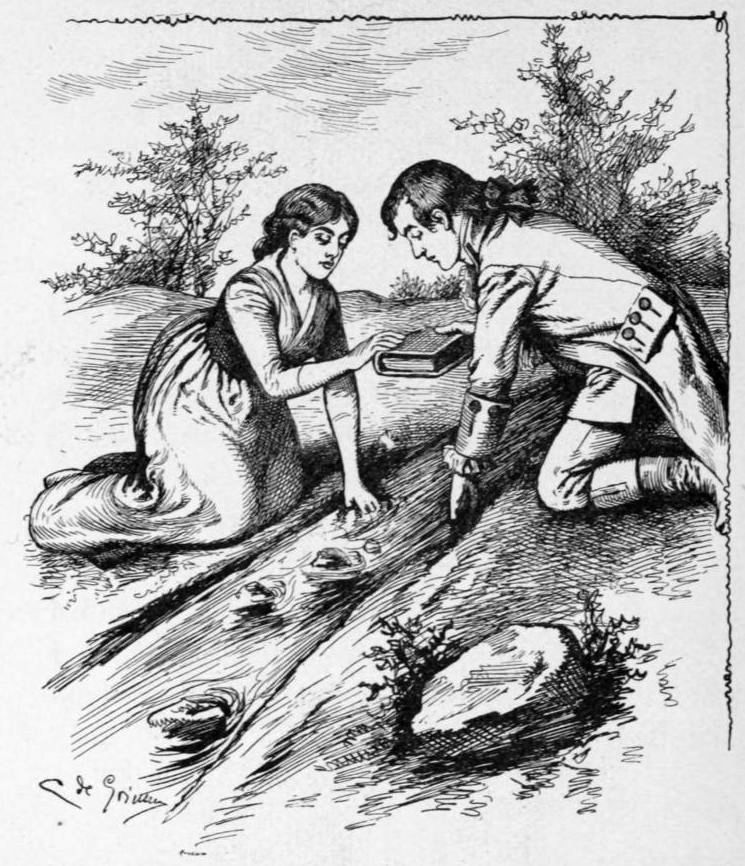

How near they seemed to me, these immortal lovers, as I stood there lost in thought by the ripplin’ waters of the Bonny Doon!

The white clouds floated along in the same blue bendin’ Heavens; the bright waters dimpled and laughed along jest as gayly and crystal clear, and their memory dominated all things above and below.

Here they stood, happy youth and maiden, beside the overrunnin’ Doon, that carries ’em on, and will carry ’em on forever, through the land of Love and of Fame.

She is a-lookin’ up with blue, love-lit eyes into his eager, ardent face. He is sayin’ to her, as he did a hundred years ago—

“Will ye go to the Indies, my Mary,

And leave auld Scotia’s shore?

Will ye go to the Indies, my Mary,

Across the Atlantic’s roar?

Oh, sweet grow the lime and the orange,

And the apple on the pine;

But a’ the charms o’ the Indies

Can never equal thine.”

And agin he is sayin’, as we imagine, with a smile and a tear in his half sad, half humorous way—

“Bonnie wee thing, cannie wee thing,

Lovely wee thing, wert thou mine,

I wad wear thee in my bosom,

Lest my jewel I should tine.

Wishfully I look and languish

In that bonnie face o’ thine;

And my heart it stounds wi’ anguish,

Lest my wee thing be na mine.”

Wall, his forebodin’ wuz correct; Death, a more triumphant and constant lover than poor Burns would have been, bore off the bonny lassie into his icy but secure realm—mebby beyend the star her bereft lover apostrophized so long afterwards a-talkin’ to her “dear departed shade—”

“Thou ling’ring star, with less’ning ray,

That lovest to greet the early morn;

Again thou usher’st in the day

My Mary from my soul was torn.”

THIS IMMORTAL PAIR OF LOVERS.

But though Death bore her off in her first sweet youth, and him long years after, a sad, middle-aged man, with a big family of children, who called another woman mother—still they stand there by the Bonny Doon.

The blue eyes and the brown eyes (that have been dust for a century) are still lookin’ love to each other.

Warm, clingin’ hands, that can hardly be torn apart, love so great that it fills the universe—love! constancy! despair! heartache! flowin’ out from the rapt atmosphere that surrounds this immortal pair of lovers; it is a power that enfolds all feelin’ hearts.

The deep emotions that sanctified that spot live on still in the heart of the world.

Devotion! heart-breakin’ grief! death! eternity! they are all brought nearer as we stand by these sparklin’ waters that flow on forever, whisperin’ the names of Robert Burns and his Highland Mary.

Other thoughts come to us anon, or a little later—thoughts of the labors and struggles of the poet to make a home and respectable livin’ for his family.

The warm poet nater, endowed, as all true poet souls are, with the fiery “love of love, and hate of hate, and scorn of scorn,” tryin’ to make its way in a practical, money-lovin’ age.

It wuz some like takin’ an eagle down from the heights, and trainin’ it to become a barn-yard fowl, or breakin’ in a wild gazelle to churn in a treadle machine.

It wuz hard work!

And the fashionable world, that took him up with the interest it would give to a new toy of a novel design, soon grew weary of him, and turned away coldly from the strugglin’ poet, in his unequal conflict with poor land, high rents, misaprehension, poverty, and hardships.

No wonder he turned away from the world at last and said to poor Jean (she that wuz Jean Armour), the wife who had been constant to him in evil and good report—

“I am wearin’ awa’, Jean;

Like snow in a thaw, Jean,

I am wearin’ awa’

To the Land o’ the Leal.

“And there I would be fain

In the Land o’ the Leal.”

No wonder he said it, poor creeter!

I spoze the gay world apoligized for its neglect and coldness by sayin’ that Burns drinked and cut up.

Wall, I spoze he did—some; but he wuz a good-hearted creeter.

And anyway they overlooked it in the first place, and ’em who worship his memory now look calmly over them faults as if they were mere specks on a blazin’ sun.

Why didn’t they do so then? Why didn’t they take a few of the posies they scatter on his cold tomb to-day (one hundred years too late) and lay ’em in the tired, hard-workin’ hands, toilin’ on at Nithsdale?

Why didn’t they take a few bits from the banquets they spread now to his memory (one hundred years too late) and give it to the half-starvin’ poet and his wife and little ones, while it would have done some good?

Why didn’t they take a little of the immense sums they spend in marble blocks and shafts to rear monuments to him all over the world, to buy a few comforts for himself and his loved ones?

For what did almost his last letter state, he had writ to a friend askin’ some relief, for without it, he sez—

“If I die not of disease, I must perish of hunger.”

Heart-sick with the tyrrany of his employers, the little minds about him, who mebby rejoiced to tyrranize over and torment a soul so much above their own. Heart-sick with the neglect of the world, he fell asleep July 21st, 1795.

About a month before his death he writ to a friend—

“As to my individual self I am tranquil, but Burns’ poor widow and half a dozen of his dear little ones, helpless orphans. Here I am weak as a woman’s tear, ’tis half of my disease,” etc.

I should think Scotland would be ashamed of herself. I honestly should, to let her greatest pride and glory die of a broken heart, caused by her neglect and heartlessness, and then praise him up so and spend sech sums of money on his tombstones, and things (one hundred years too late).

But, then, it’s a trait in human nater. Scotland hain’t the only country that duz it.

It is nateral to torment and torture the soarin’ bird of Genius, and pluck out the plumage from its quiverin’ flesh one at a time—cut its feathers down, hang weights to its wings, and act.

And then when the agonized and heart-broken soul has took its flight out of the tortured body, to stuff that soulless effigy with the softest and warmest stuffin’ of praise and appreciation, put jewels in the blind eye sockets, cover the cold breast with diamond bright stars of praise, and lift it up on high, up on top of the soarinest monuments they can raise to its honor.

Too late, too late!

But I am indeed a-eppisodin’; and to resoom.

Everybody in the village had sunthin’ to say of Burns. Everybody wuz proud of livin’ in the place his feet had once trod.

Them who looked the coldest on him when livin’, or descendents of them who had wrung his sensitive soul while warm and beatin’, and achin’ for sympathy—

Descendents of the big man of the village, “Holy Willie” himself, who once would not have spoken to his humble neighbor, or if he’d spoken at all, they’d been words of insult that would have rankled in the soul of the poet, now considered it their greatest pride and honor to live in the country that gave him birth.

The cottage is a low, long buildin’ only one story high. And jest think of it, how many are born in five-story houses that nobody hears from afterwards. The roof is thatched, the floors are stun, clean and white. A cupboard full of dishes stood on one side of the room.

There wuz some letters that Burns writ with his own hand. I thought more of seein’ ’em than any of the other relicks. Letters that his own hand rested on—his own ardent, handsome face had bent over. What emotions they gin me; I never can tell the heft and number on ’em.

Yes, the thought of Burns filled the place, jest as some strong, rich perfume fills the hull room where it has been spilt.

I didn’t hear much of anything said about Miss Burns (she that wuz Jean Armour), but I took quite a considerable spell of time and devoted it to jest thinkin’ about her. I didn’t think it wuz no more’n right that I should.

I spoze she felt real proud to be the wife of sech a great man, and it wuz a great thing. But, then, she had her troubles. Poor thing! patient, hard-workin’ creeter! Washin’ dishes, mendin’ clothes, takin’ care of the children, takin’ all the care she could of her husband. And then when she got him all mended up for the week, and as good vittles for him as she could with what she had to do with—then to have him a-writin’ verses to other wimmen!

A-takin’ the strength her own pot-pies and puddin’s had gin him, and a-spendin’ it all on writin’ verses to other females.

His heart a-beatin’ voyalent aginst the vest she had newly vamped for some other “Chloris” or “Clorinda” or etc., etc., etc., etc.

A-walkin’ off in the stockin’s she had new heeled to catch a glimpse of some “lassie wi’ lint white locks,” so’s he could put her rustic beauty into rhyme.

A-throwin’ himself down in a good coat that she’d jest washed and fixed up, to look up into the sky and apostrofize some other female up in Heaven.

It must have been tough on Jean—fearful gauldin’ to her!

But, then, mebby she wuz willin’ to have the fire of his genius catch a brightness and glow from any object. And woman’s beauty wuz always, to Robert Burns, what the very best kindlin’ wood is to me when vittles are to be produced in a hurry.

Mebby she looked on it with a lenitent eye—most likely she did, or she couldn’t thought so much on him as she did.

I guess he wuz a good, tender husband to her, and a good provider, so fur as his means went.

But thinks I, here is another sample of the devotion and constancy of my own sect. I thought on her about 17 minutes.

Other tourists may foller my example or not, jest as they think best, but I done it, and am glad on’t. But to resoom.

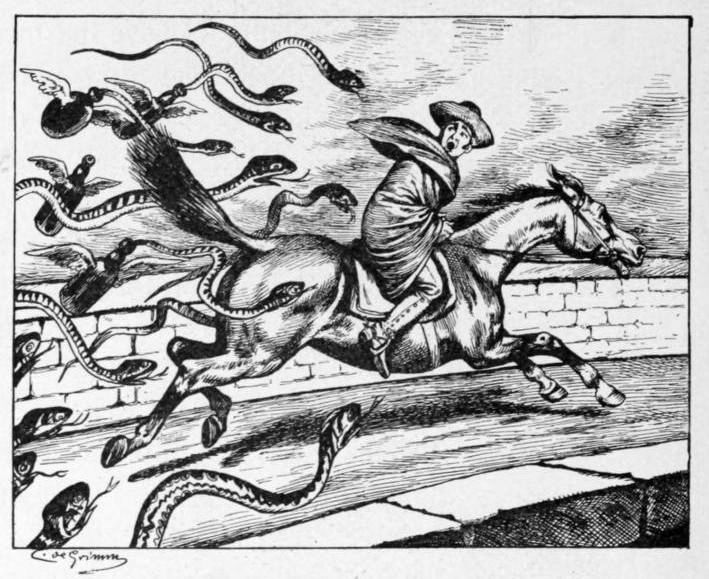

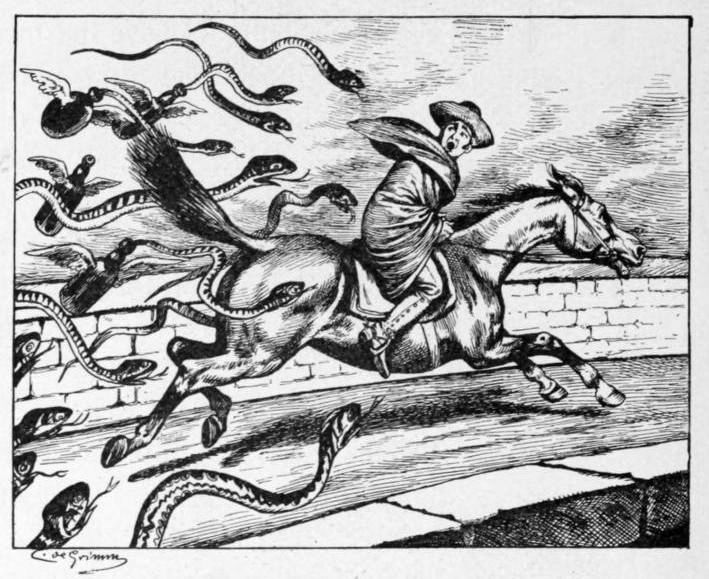

We then went to see the old Bridge of Ayr, whose single arch connects each green shore. It wuz over this bridge that Tam o’ Shanter rode on the old mair Maggie, pursued by witches, “Wi’ mony an eldritch screech and hollow.”

And I eppisoded some. I have to in the strangest places. I methought that the same furies that pursued the drunken Tam is still sold in the same old inn, and even in the very birthplace of the poet.

THE SAME FURIES THAT PURSUED THE DRUNKEN TAM.

The same sperits of delerious fear, and senseless terror, are bought and sold at so much a glass. Poets live and poets die—empires rise and empires fall, but whiskey has to be sold jest the same. Drunkards race through their sottish lives, hag rid by the furies of drink and debauch. And mairs have to be rid to death, and have their tails cut off.

Sez Josiah, “It wuz probble a witch that cut off the mair’s tail.”

Till he answered me, I hadn’t mistrusted that I wuz a-eppisodin’ out loud.

Sez I, “That is to tippify how drunkards abuse their animals, most likely,” sez I, “and to show that these foul sperits don’t have no power where pure water is in full sway.

“The drink demon hates water,” sez I.

But Josiah sez—“Wall, wall! I didn’t walk out here to hold a Temperance Meetin’!” Sez he sarcastickally, “This hain’t a Total Abstinence Society!”

Sez I, “It’s a pity there wuzn’t one here a hundred years ago!” Sez I, “Probble it would have saved poor Burns from a good deal that he went through, and,” sez I, “it would be a-settin’ a different sample before young folks from the one that wuz sot, and is still a-settin’—a sample his genius, and noble qualities, and his light-hearted good nater tempt ’em to foller.”

Sez Josiah, “Hain’t you got a Temperance Pledge round you, Samantha, or some badges, or some banners, or white ribbins, or sunthin’?”

Sez he ironacly, “I could carry a banner with ‘Temperance’ or ‘W. C. T. U.’ on it jest as well as not, and I’d ruther lug it round and be done with it than to have to everlastin’ly hear on’t.”

“Wall,” sez I soothin’ly, “we will go back now and have a good lunch.”

And as we wended along, I meditated that mebby I hadn’t gin enough thought to my pardner’s feelin’s. For truly mortals have not now any more than in the time of Burns the “gift to see oursels as ithers see us.”

But I wuz upheld by thinkin’ I’d talked on principle, and that is a dretful upholdin’ thought.